This editorial appears in the Fall 2019 issue of Modern Age. To subscribe now, go here.

The world of today was born thirty years ago. The same year the Berlin Wall ceased to divide Europe, the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party ordered the massacre of hundreds if not thousands of protesters in Tiananmen Square. Francis Fukuyama published “The End of History?” in the National Interest as the Cold War drew to a close. For more than four decades, that struggle between communism and Christianity, capitalism, and nationalism had defined much of politics—within the West as well as between West and East. But in 1989 a new era was dawning, a liberal era whose hopes were belied by the bloodshed in Beijing. Communist economics was at an end; communist despotism was not.

Capitalism, perversely, would give communist rule in China a new lease on life. In the West, intellectuals celebrated liberalism as the victor of the Cold War, with religion and patriotism discounted steeply. Pope John Paul II and the faith of his fellow Poles had made a contribution to the downfall of European communism in the 1980s. And, yes, the fact that Germans and Hungarians and the rest did not want to be ruled from Moscow was important. But as far as the intelligentsia of Western Europe and the United States was concerned, these facts had little meaning for us: our freedom did not depend on faith or national loyalty; it depended rather on secular universal ideals, those of liberalism and democracy. If capitalism was the salvation of communism in China, in the West a liberalism that shared communism’s scientific pretensions and disregard for religion and national boundaries became the new orthodoxy of the elite. The Cold War ended with irony, not a storybook finish.

And since then we have seen the consequences of drawing the wrong lessons from the failure of Soviet communism. The world’s industrial production has shifted heavily toward a still-unfree China, while the West has been wracked by a sense of betrayal and spiritual anomie that is often most intensely felt in the places denuded of those industries that have moved abroad. Could religion comfort those whose work has been disrupted by trade and technology, the very prizes of the modern global economy? Yet the same forces that have worked to transform jobs have privatized and atomized religion as well. Libertarians and social conservatives often misunderstand one another here. Libertarians may care as much as or even more than everyone else about their families or their country, but philosophically libertarianism sees these things in voluntaristic, arbitrary, market terms—if you choose to value these things, then great. But if you choose not to, that is your choice, and no one may gainsay you except in the court of public opinion. And even then, public opinion in a society where attitudes are molded by progressive media and educational institutions is unlikely to be very sympathetic to culturally conservative choices.

On the other hand, cultural conservatives themselves are prone to misunderstand the alternative, which is not a world where choice counts for little and truths can be rigorously enforced. A human nature that is divinely ordained or philosophically known, that is not reduced to passions and preferences, is not a blueprint or instruction manual for society or politics. The variety and mystery of human experience require a supple politics, guided by the ideal but modified to take account of circumstances and human particularities. There is plenty of room for liberty in this, but it is a liberty predicated on a different understanding of human beings than one finds in economic textbooks or among the works of social-contract philosophers.

A generation past the Cold War, America and the West have need of their own Berlin Wall moment, not to tear down an instrument of political oppression but to throw out the ideological baggage of an earlier time, when secular liberal universalism seemed as much the wave of the future as Soviet Bolshevism had once seemed to overeager American leftists like John Reed. The essays in this issue of Modern Age take liberalism and its limits seriously, as well as the problem of establishing a free yet virtuous polity, one in which there is a transcendent standard of excellence, yet also a necessary allowance for the fallen nature and unavoidable divisions of mankind. ♦

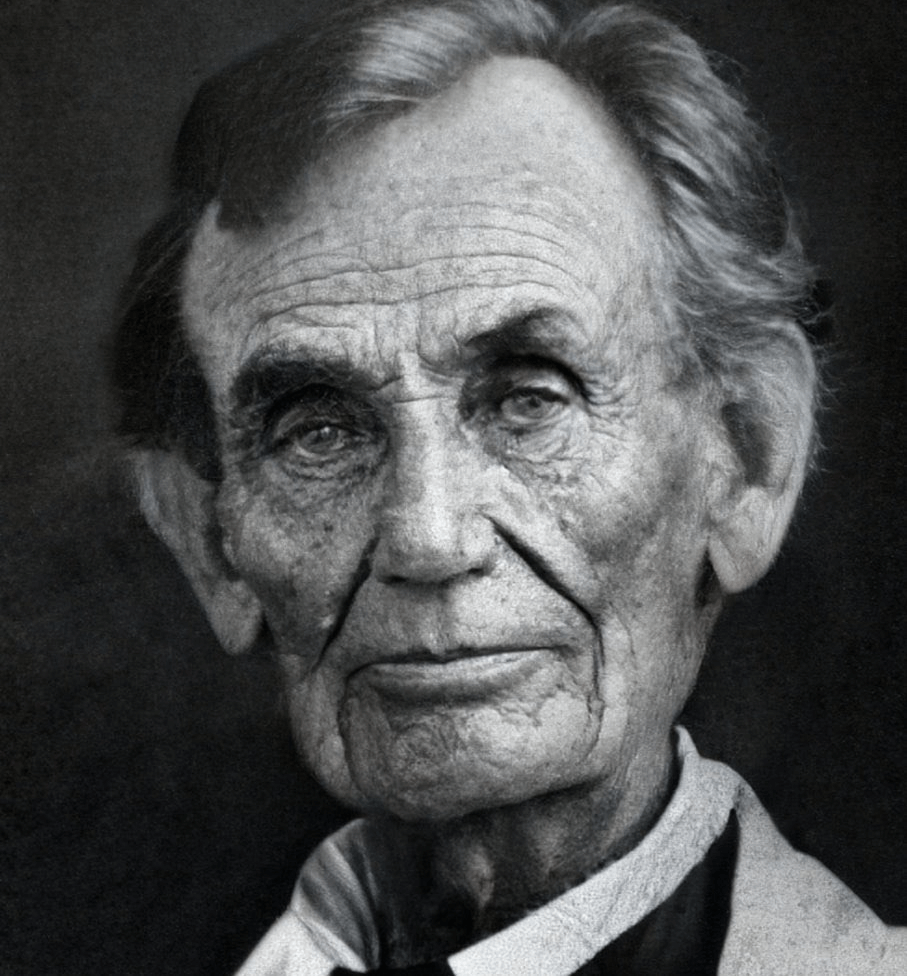

Daniel McCarthy is editor of Modern Age.

Founded in 1957 by the great Russell Kirk, Modern Age is the forum for stimulating debate and discussion of the most important ideas of concern to conservatives of all stripes. It plays a vital role in these contentious, confusing times by applying timeless principles to the specific conditions and crises of our age—to what Kirk, in the inaugural issue, called “the great moral and social and political and economic and literary questions of the hour.”

Subscribe to Modern Age »