New eras, whether in religion, science, or politics, usually begin with a book. When The Conservative Mind was published by Regnery in the spring of 1953, few suspected the book was the harbinger of the most important political changes of the twentieth century. Its author, Russell Kirk, was an unknown assistant professor at a Midwestern cow college whose president had been a professor of poultry husbandry. Providence has a strong sense of irony.

The previous summer Henry Regnery, while on vacation with his family at a farm he owned in West Virginia, read the impeccably prepared manuscript. Regnery knew immediately “that this was an important and perhaps a great book.” The manuscript had been found—perhaps discovered is the better word—by Sidney Gair, who had been an old-fashioned bookman with a large eastern publisher. It is a matter of interest that it is unlikely today that any bookman, hawking texts from campus to campus, would be able to distinguish Edmund Burke from Karl Marx.

The book appeared at an opportune, a providential, moment. The crack in the picture window of modern liberalism had been steadily widening. Shortly after the publication of The Conservative Mind, Dwight MacDonald could still speak contemptuously of “scrambled eggheads on the Right.” Only ten years before the publication of The Conservative Mind the Thesaurus of Epigrams (New York, 1943) listed twelve epigrams under the heading “Conservative,” one more mindlessly derogatory than the other. The prevailing academic wisdom in the faculties of history, politics, literature, and economics was that the American nation was the fulfillment of liberal utopianism. Little wonder that Kirk suggested as a title for his book “The Conservative Rout.” As an alternative Sidney Gair suggested “The Long Retreat.” Neither title displayed much optimism as to the future of conservatism.

Still, there were numerous evidences of a growing dissatisfaction with the world liberalism and the ideologies with which it was associated had made. Halfway through the war against statism in its ultimate totalitarian form Friedrich A. von Hayek’s Road to Serfdom appeared and enjoyed an enormous success. The epigraph which introduced Hayek’s book was a quotation from Lord Acton, and in Europe and America in the years following World War II a revival of interest in Lord Acton was under way. The publication of a translation of Jacob Burckhardt’s Reflections on History and an abridgment of his letters, both commanding a wide reading audience, deepened the mood of pessimism in thoughtful people as they regarded the growth of statism.

The revival of interest in Alexis de Tocqueville underlined and strengthened the observations of Acton and Burckhardt. Then came the publication of William Buckley’s God and Man at Yale in 1951, though it is well to remember, as Regnery has pointed out, that the word conservative “is hardly used: Buckley then described his position as ‘individualist.’” Russell Kirk’s book had the effect of a seed dropped into a supersaturated solution. Conservatism crystallized out around it. Kirk provided a distinguished pedigree for American conservatism and demonstrated that, far from being a minor and subordinate tradition in the American past, it was the perennial character of the American experience.

Kirk provided a distinguished pedigree for American conservatism and demonstrated that, far from being a minor and subordinate tradition in the American past, it was the perennial character of the American experience.

The overwhelming success of the book surprised everyone. In the days when Time magazine spoke with authority Whittaker Chambers called The Conservative Mind to the attention of Roy Alexander, editor of Time. The entire book section of the July 4 number of the magazine was devoted to it. A highly favorable review by Gordon Keith Chalmers, President of Kenyon College, appeared in the May 17 New York Times Book Review. Other national newspapers and scholarly journals were equally appreciative of the book’s qualities. Conservatism as a cultural and political movement had been launched. Interest in Edmund Burke had throughout the 1940s been steadily increasing. Kirk made Burke the model conservative and did much to stimulate the flood of Burke scholarship which followed the publication of The Conservative Mind.

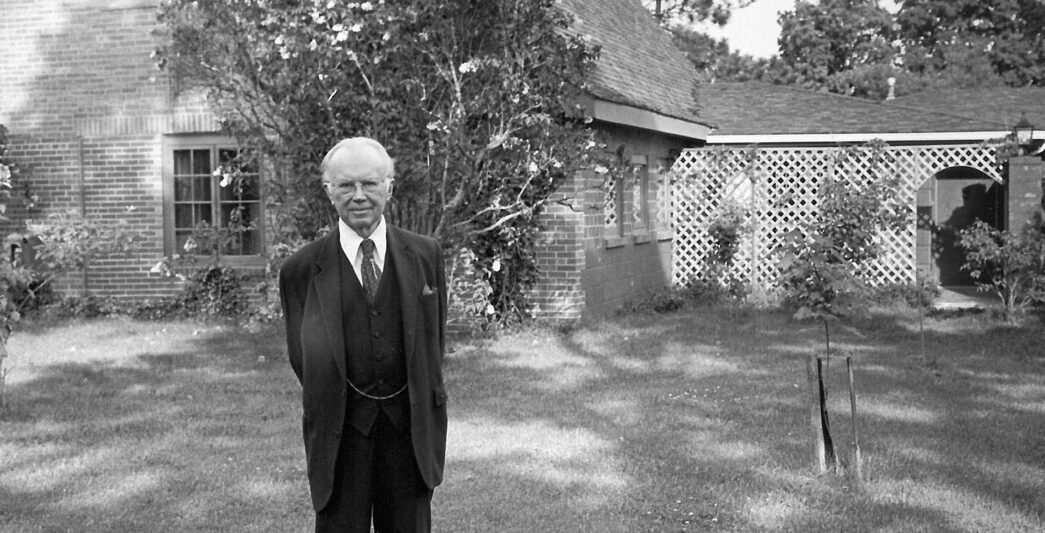

Russell Kirk was not an academician. Although he held a doctorate from St. Andrews University in Scotland he did not much value the safety and ingrownness of the university campus. It is not surprising that he abandoned teaching at Michigan State and through writing and lecturing devoted himself to a national classroom. He thought of his mission much as Emerson thought of his public obligation. Kirk estimated that he had lectured on five hundred campuses. He was, in the formative years of the movement, the voice of conservatism. And he wrote: scholarly books and articles, columns for newspapers and journals, fantasy and gothic novels. Whether his topic was politics, culture, education, or entertainment his purpose was undeviating. His goal was to reform and transform America. For many years he worked without research or secretarial assistance and to the end of his life he typed his letters. Few men have worked harder or have been more dedicated to what they believed to be their civic responsibilities.

In the summer of 1957 Russell Kirk brought out the first number of Modern Age. It was a journal whose purpose was the provision of an intellectual base for the conservative movement. To its pages Russell Kirk attracted the finest and keenest minds on the right. One marvels at Kirk’s ability to add the heavy duties of journal editorship to all his other activities.

Amid this flood of print, Randolph of Roanoke, published by the University of Chicago Press in 1951, and hence antedating The Conservative Mind, and Eliot and His Age: T. S. Eliot’s Moral Imagination in the Twentieth Century (1971), will endure not only as important scholarship but also as index of the mind that created them.

Russell Kirk was a shy and thoughtful man. His conversation was not the dazzling conversation of a Dr. Samuel Johnson. His métier was the written word. Sidney Gair wrote Henry Regnery describing Russell, “the son of a locomotive engineer, but a formidable intelligence—a biological accident. He doesn’t say much, about as communicative as a turtle, but when he gets behind a typewriter, the results are most impressive.”

Russell would refer to himself, from time to time, at dinner parties as a “turtle.” However taciturn, he was a good listener.

Gair’s characterization hardly got at the man. It neglected to say that he was a person of absolute integrity, generous to a fault, charitable even when charity was a mistake, hospitable, and lovable. Few public figures have made so few enemies and those few enemies, for the most part, were men who misunderstood him.

Russell Kirk was fond of describing himself as a “Bohemian-Tory.” That he was a bohemian was a conceit which ranks with the fantasy stories he produced. There is no doubt, however, about his being a “Tory,” though just what “Tory” means in the context of Mecosta, Michigan, might be difficult to explain. My colleagues in the political science department, half in derision and half in envy, called him “the Duke of Mecosta.” It is true that he became a justice of the peace and took as much pride in the fact as Gibbon took in being a member of the Hampshire militia.

His politics were statist in the Burkean sense. He believed that the state was instituted to make men more virtuous than they naturally are and to do those things necessary to the good life which men, acting as individuals, cannot achieve. As a consequence of this belief he was opposed to individualism, libertarianism, and any excessive role or scope for the market economy. Half of the contemporary conservative movement was terra incognita to him, a land filled with wild beasts and monsters. He was a conservative, a traditionalist but not a “man of the Right” as Whittaker Chambers described himself.

In the New York Times’s Chalmers review of The Conservative Mind, the Times set off in a little box, as it often does, a lengthy quote from Kirk’s book, a quotation which gets at the essential message of the book. Kirk wrote: “Conservatives must prepare society for Providential change, guiding the life that is taking form into the ancient shelter of Western and Christian civilization.” To which most conservatives can shout “Amen!” However, the task of translating the “permanent things” into forms which could accommodate the world of change, the world of history, eluded Russell Kirk.

This was ironically clear at the celebration at Dearborn Inn of the fortieth anniversary of the publication of The Conservative Mind, and Russell Kirk’s seventy-fifth birthday. The Dearborn Inn, standing in the vicinity of Greenfield Village, had been built by Henry Ford. Russell in his after-dinner talk mentioned how, as a young man, he had worked as a guide to the museum and the historic houses of Greenfield Village. Perhaps no man so transformed our world in a sense repugnant to Russell Kirk as did Henry Ford. With his usual charity Russell said it was “alright” since Ford in the museum and the historic houses of Greenfield Village had tried to save the best of that past. However, the “permanent things” cannot be saved by moving them to the historical museum of Greenfield Village. To endure they must be recast in contemporary forms and idioms.

The vision from Mt. Nebo is always a partial one and we ought not to ask more from one who has done so much. Let us praise a great man whose vision enables us to take up the task of recasting “the permanent things” into the living reality of the present.

Stephen Tonsor was an author and a professor of history at the University of Michigan.