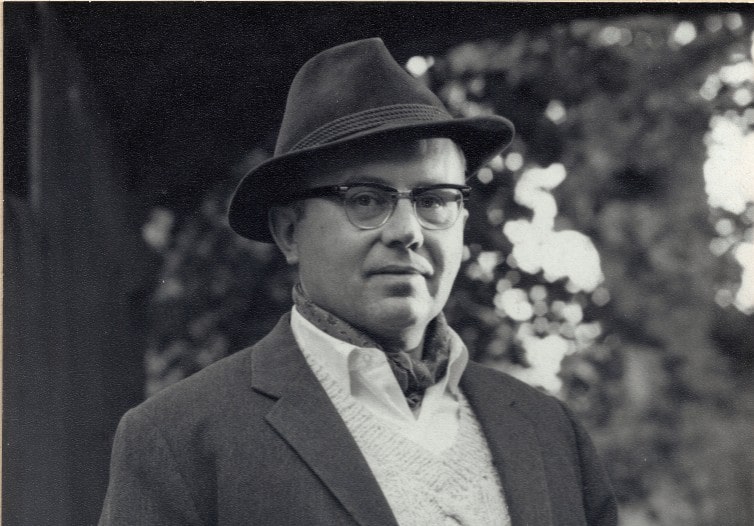

Last year on February 25, Paul Cantor, an outstanding scholar of Renaissance and Romantic literature as well as contemporary culture, passed away. He was seventy-six. Cantor was not just an eminent scholar of the European Renaissance but a Renaissance man himself in the sphere of arts and letters. Whether the subject was classical music or the history of painting or belles-lettres or the worlds of popular entertainment and sports, his knowledge was vast and his insights were subtle and nuanced. (For years he hosted a radio show in classical music; later he did most of the programming selections for the Tuesday Evening Concert Series at the University of Virginia.)

The memorial tributes of the past year focused, and justly so, on Cantor’s remarkable achievements as a literary scholar and public intellectual. I was privileged to know him not only as a scholar but also as a teacher, mentor, and friend. Those dimensions of his life—in many respects even more noteworthy than his accomplished career as a scholar-critic—warrant equal attention.

Paul was thirty-four, and already a Shakespeare scholar of national standing and the author of research articles that would form the basis of a pathbreaking study of the English Romantic poets, when I met him in 1979 as a twenty-two-year-old first-year Ph.D. student at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, where for forty-five years he would regularly teach large lecture courses and Ph.D. seminars alike. He had then recently arrived from Harvard, having spent a decade there as an undergraduate, Ph.D. student, and junior professor, and where he had completed his first landmark study, Shakespeare’s Rome: Republic and Empire, a deeply learned treatise addressing the classical heritage of Shakespeare’s Roman plays. Cantor published that first book in 1976 at the age of thirty.

Despite Paul’s youth and junior faculty status at Harvard, he was a renowned and beloved lecturer even in his mid-twenties, impressing undergraduates with his consummate grasp of the subject matter and outrageous sense of humor. At Virginia he would be expected to teach advanced Ph.D. seminars too. Most faculty colleagues conceived of doctoral courses—and still do so today—as student-centered sessions in which the attendees contribute to discussion and present their own research. By contrast, Paul’s “seminars” often turned into something approaching three-hour monologues, for he held that any student-centered class was little more than, in his phrase, “shared ignorance.”

Relatively speaking—that is, when we students compared our meager knowledge to his own masterly grasp of whatever reading was assigned that day—Paul was quite right. I was shocked, and then delighted, that Paul readily dispensed with the “sham pedagogy” of jump-starting class discussions. Believing that he had a vast wealth of intellectual treasures to share—and a mere three hours vouchsafed to him weekly—Paul wisely concluded that maximum economic efficiency obliged him to lecture, straight out and nonstop. So thoroughly captivated were I and most of my friends by Paul’s lectures—much later versions of which, on Shakespeare, are immortalized today on YouTube—that I even mildly resented students’ questions. (More so than Paul himself did, since he announced to the class, in a magnanimous concession to the vagaries of the student audience marketplace, that “interruptions” were “not unwelcome.”)

Does Paul’s seminar style give the impression that he was uninterested in students and what they thought? Nothing could have been further from the truth. Although his candor and confidence could be mistaken for arrogance, he despised pretension and mocked obscurantism. He enjoyed talking at length with students after class or in his office—or, once you got to know him better, at his condominium. What did I, a poorly read boy in my early twenties from an immigrant Irish family and a small Catholic college, have to give him? Nothing except an eagerness to share ideas and an innocent wonder about the life of the mind. Yet Paul “wasted”—my word, not his—numerous evenings in his condo with me, during which he often said that he learned an enormous amount from his students, and even credited them for having alerted him to outstanding new TV shows or new trends and tactics in sports.

There I listened to his stories of having attended, as a fifteen-year-old junior from Samuel J. Tilden High School in New York City, the at-home seminars of Ludwig von Mises, the preeminent dean of Austrian economics, which were conducted in the style of a European salon and attended by Mises’s colleagues and guests, including Murray Rothbard and Friedrich von Hayek. On another night he regaled me with his schoolboy memories of having seen Morris Carnovsky twice in the role of King Lear at the Stratford Shakespeare festival (“the most exhilarating Shakespeare performances I ever witnessed”), which galvanized him to write two student theses, first as a graduating high school senior and again as a Harvard senior, on King Lear.

In Paul’s condo I watched Hulk Hogan in a mock-serious mano a mano with André the Giant, and the villainous tag team of the Iron Sheik and Nikolai Volkoff argue with the beleaguered refs and try to cheat their way to victory, all of it with Paul’s side-splitting commentary. (I was forever asking him to compare these wrestlers with my own favorites during my elementary school fandom days, wondering how Bruno Sammartino or Professor Tanaka stacked up against Sgt. Slaughter or Ivan “Russian Bear” Koloff.) Fully aware that it was all staged, Paul nonetheless gloried in the charade with a boy’s uninhibited excitement and enthusiasm for each new twist and turn in the action until—as always—the loveable American Good Guys would prevail against the funny-talking foreigners, who would break all rules and stop at nothing yet still fail to win. (As Paul would note two decades later in his brilliant essay, “Pro Wrestling and the End of History,” national clichés and ethnic stereotypes were an integral part of professional wrestling in those days, and Paul laughed about it all.)

Doubtless my most unforgettable visit to Paul occurred one night when I casually picked up the proof pages of his forthcoming book on Romanticism, Creature and Creator (1984). Flipping through the volume, which Paul had already mentioned both in conversation and in lectures, I shouted my congratulations. Paul was in the kitchen, whipping up a meal (he was an excellent cook and a formidable connoisseur of wines), and he called out, “What page are you on?”

“Page 63.”

“When Blake set out to write The Four Zoas, he was trying to find a way to incorporate the historical events of his own time into a cosmic mythic framework. But as he worked on the poem, his . . . ”

My eyes were fixed on the page. Paul was reciting, word for word, the first three lines of print.

I was thunderstruck. And dumbstruck. Silence reigned for an eternal moment. Whereupon Paul called out again.

“Pick another page.”

“Page 184.”

And again, as if he had a teleprompter in the kitchen, Paul repeated the text back to me, unerringly, word for word, from the half-sentence on the first line to the bottom of the page, which ends with a half-completed last sentence in the last paragraph: “From the very first moment of his vision, Shelley is questing for origins. But the crowd of men he sees is oblivious of either pole of Romantic . . . ”

I had known Paul for five years by this time. Never once had he mentioned this gift. Nor had I heard about it from classmates. Apparently he regarded it as little more than a party trick. Soon thereafter, he invited me for dinner again. As he cooked, I pulled a book out of the bookcase, calling to Paul in the kitchen that I was holding Natural Supernaturalism, M. H. Abrams’s classic study of the origins and evolution of Romanticism.

“Have you recently read it?” I asked.

“Years ago,” he called back. A pause. “What page are you on?”

“Page 322,” I replied, concealing my excitement (and residue of Doubting Thomas incredulity), wondering if the feat of photographic memory could be repeated.

Sure enough, Paul delivered exactly the same boffo performance for three different pages from a book he had read a decade earlier.

Now I had no doubt. If any skeptical part of me had been thinking after the first visit, “Well, he was proofing his own book. Maybe those pages just stuck in his memory,” I surrendered to the fact of Paul’s own “natural supernatural” power of memory once and for all.

I came to refer to these pre-dinner speaker performances as “Paul’s Shout-Outs.” I learned more about them four decades later, in March 2022, at Paul’s memorial event in Charlottesville. His closest high school friend told the guests that, as a ninth grader, Paul had played a “memory game” regularly. It consisted of the friend pulling out books and magazines that Paul had read and “testing” fourteen-year-old Paul’s verbatim recollection of them.

While I had always been impressed by Paul’s casual, seemingly encyclopedic range of reference to classical orchestra recordings (his CD collection numbered in the thousands), I learned in 2021 from a colleague in the University of Virginia’s music department that Paul could remember every recording that he had ever heard, and thereby recall with authority numerous versions of a work. No wonder, she said, that he—not a member of the Department of Music—was tapped as the programming advisor for the university’s live music schedule.

And those friends who ever visited an art museum with Paul will testify to the discombobulating experience of trying to keep up as Paul sprinted from one room to another at what felt like breakneck speed. For Paul could cover several large rooms in a half hour, taking in every visual detail in a flash, then checking his photographic memory and remarking en passant on a comparable painting from the Hieronymus Bosch show at the Prado in Madrid or at the Vermeer exhibition years ago in Dublin—or was it Amsterdam or London or Basel?—even as the straggler (i.e., his awestruck slowpoke companion) was still grappling mentally with the first picture in the first room.

***

“Rarely does a literary critic display the kind of genius and creativity characteristic of the famous authors he analyzes,” wrote Paul in his insightful memorial appreciation of Harold Bloom, who died in 2019. Certainly Paul’s words applied to Bloom, a towering literary critic and polymath, a fellow Romantic literary scholar of encyclopedic learning (and, reputedly, a photographic memory) from whom Paul learned much and whom he regarded as a kindred intellectual spirit.

Yet those words applied equally well to Paul himself. As did his next observation: “Over a long, distinguished, and varied career, he reinvented himself several times.”

Starting out as a Renaissance scholar specializing in Shakespeare and the relationship between Elizabethan England and classical Rome, Paul went on to establish himself as a scholar of English Romanticism—the field in which he chiefly taught throughout the 1980s when I got to know him at Virginia. By the late 1990s, he was not just discoursing on television in his condo and tossing out a few thoughts on it in a Romanticism lecture. Rather, he was beginning to go public, starting with a series of essays that culminated in the publication of Gilligan Unbound: Pop Culture in the Age of Globalization (2001), whose dedication read: “In memory of my devoted VCR Sony SLV 240. . . . July 20, 1994 – December 29, 2000.”

Paul spent the last decade of his intellectual career combining all these fields, as well as publishing widely on Austrian economics, in pioneering books such as Literature and the Economics of Liberty (2009) and The Invisible Hand in Popular Culture (2012), where he applied the insights of Mises and Hayek to the television industry and other domains of popular culture. (Paul was tickled that Michel Foucault advised his disciples, in The Birth of Biopolitics—a series of Collège de France lectures delivered a few years before his death in 1984—to read the work of Mises and Hayek “with special care” in order to honor classical liberalism’s “restraint” and its respect for the wisdom of the market.)

A prolific author, Paul remained a superlative lecturer and inspiring classroom teacher. Yet now he also took his teaching to the wider public, sitting for interviews with Bill Kristol (another of his former students), developing a much-trafficked website that showcased his work, and delivering lectures that were uploaded to YouTube and other platforms. Unsurpassed are the Harvard lectures in the “Shakespeare and Politics” series and the “Culture and Commerce” talks for the Mises Institute. He once declared that the Harvard lectures on King Lear, which was the work that Paul regarded as the Mount Everest of Shakespeare’s Himalayan oeuvre, represented the “proudest accomplishment of my career.”

As in my days in his classes decades earlier, Paul speaks in these YouTube lectures with a depth of understanding and—all too rare in an academic setting—both a marvelous lucidity and an extraordinary capacity to encapsulate complex ideas in arresting, original formulations. All of it was delivered with the quintessentially Cantoresque touch, imbued with rich humor and distilled so that any intellectually curious listener can readily grasp the essentials.

After he began to publish on television and popular culture, on the few occasions that he spoke on, say, Gilligan’s Island or Hulk Hogan and the Worldwide Wrestling Federation at academic conferences, the flabbergasted audience was rolling in the aisles with laughter. Never had they beheld such a synthesis of revelatory insight and soaring hilarity—such a comical yoking of the high and the low. It seemed bizarre if not somehow profane to invoke thinkers and artists such as Alexander Kojève, Francis Fukuyama, and Samuel Beckett in an analysis of the Hulkster, as if a professional comedian had just been prepped on arcane literary theory and hired to explode the pretentious humbug of an academic conference. (“That’s my secondary motive,” Paul might well have allowed.)

Professional comedian? A close second in Paul’s “proudest moment” hit list would surely be his introduction to Johnny Carson at Harvard in the mid-1970s, which Paul treated as opportunity to deliver a warm-up act that brought the house down—whereupon Carson remarked: “I think this guy is trying to steal my show!”

A lifelong cultural conservative and staunch defender of the Great Books and Western civilization, Cantor was nonetheless also a daring cultural radical who remained intensely curious and ever receptive to the new. More clearly and effectively than any other literary scholar-intellectual of our time, he made the case for television as a mature creative medium that had come of age “in classic shows like Seinfeld, The Simpsons, and The Sopranos” and challenged traditional high culture scholars such as myself to take TV seriously.

His arguments—and accusations—hit home with me. And I was not alone. As he wrote in “Get with the Program: The Medium Is Not the Message” (2010):

Critics who castigate television assumed that the television they grew up with would basically stay the same forever. Having formed their negative opinion of the medium at an early point in its development, they refused to recognize how fundamentally [it has] changed over the years. . . . [S]ome academics still resist the idea that anything of genuine and lasting artistic value can be found on television. This resistance seldom results from empirical study, that is, from actually watching the TV programs. . . . Rather, it usually takes the form of a blanket condemnation of television as a medium, a dismissal in principle that relieves the critic of any need to bother with studying the individual programs. . . . I suppose even the most culturally conservative critic would have to admit by now that great movies can be made. But the idea of “great television shows” still seems like an oxymoron to many people. . . .

Great works can be produced in any medium—that is the challenge that great artists have risen to whenever a new one has come along. I would love to have been present to hear the nay-sayers when Aeschylus took the “goat song” (that is what tragedy means in Greek) and said that he was going to use this new—and . . . vulgar—medium to portray stories out of the divine Homer. Decades later, the original academic, Plato, was still complaining about it.

This was radical thinking indeed—and yet, as always with Paul, it was in the service of a principled conservative allegiance to the highest aesthetic standards. “I am not a sociologist,” he stressed, “but a literary critic, and am primarily interested in television as an art form, and whether individual programs have achieved a high level of aesthetic sophistication.”

In the process of venturing into ever broader domains of cultural expression, and considering each of them with a fresh eye and open mind, Paul also became a more generous critic, and a more sympathetic and generous human being. For decades, he had felt aggrieved that his contributions to Shakespeare scholarship were undervalued. Instead a “rival”—the Harvard scholar Stephen Greenblatt—had become the reigning Shakespeare authority of their generation, which was the role to which Paul had aspired.

Widely regarded as one of the greatest Shakespeare scholars of the last half century, Greenblatt, who in the 1980s revolutionized Shakespeare studies as the founder of the neo-Marxist theoretical movement known as the New Historicism, renounced his entire career of cultural materialist interpretation of Shakespeare three decades later. Greenblatt had rocketed to academic stardom in 1980 after the publication of Renaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to Shakespeare. Here and in subsequent studies he repudiated the long-established view of a humanistic Shakespeare of universal genius that the famed British scholar A. C. Bradley, a hero of Paul’s youth, had introduced at the turn of the century. Instead Greenblatt argued that Shakespeare was no universal genius; his outlook was rooted in Elizabethan England, his work reflected the imperialist and colonialist shibboleths of his day, and his much-touted plays reflected and reinforced racism, sexism, Eurocentrism, and class privilege.

Decades later, in a stunning (and courageous) about-face, Greenblatt published Shakespeare’s Freedom (2011), which effectively endorsed Bradley’s ethical, humanistic approach to Shakespeare and completely rejected a historicist, post-structuralist approach to Shakespeare’s poetry and plays. In academic terms, it was as if Saul had gone over to the Christians. That is, with minor differences, Greenblatt converted to a position no great distance from Paul’s own. As I mentioned, Paul had always considered Greenblatt to be his intellectual rival, the Henry IV—or Richard III—who had usurped his throne. Greenblatt was the Harvard man who had displaced him: the flashy, fashionable trendy-lefty Theorist who had stepped in and upstaged him to become the paramount Shakespeare scholar of their generation. Greenblatt had, as it were, forced Paul out of Renaissance studies altogether, and even out of traditional, “serious” literary studies itself—ultimately to good effect, by compelling him at last to engage with full intellectual seriousness the aesthetic achievements of American popular culture. From that perspective, Paul could be at peace, and indeed even feel grateful to Greenblatt.

Yet in his generous and admiring review of Shakespeare’s Freedom, Paul did not gloat or indulge in “I told you so” reminders, let alone mock Greenblatt’s belated act of “self-refashioning.” Instead he discussed Greenblatt’s tacit retraction-cum-apologia by simply noting the change of position, expressing a lifelong esteem for the ingenuity of Greenblatt’s previous work, and welcoming the Prodigal Son home. Thereafter Paul continued to state sincerely and publicly, as he had before, that Greenblatt was the most imaginative and influential Shakespeare scholar of their generation. In the review, Paul did allow himself the observation that a superb critic like Greenblatt was far too intelligent to go on forever freighting Shakespeare’s sublime flights of creative freedom by foisting on the plays an ideology such as New Historicism, even if the critic’s scholarly career was profiting from the haute couture revisionist agenda. Paul added that he suspected that Greenblatt, for all the genius and ingenuity of his previous interpretations, always must have felt that Shakespeare was too expansive, too colossal a creative artist to be cut and fit into a Procrustean bed of abstract theory: “I am not surprised to see that [Greenblatt has] broken out of the historicism that I always felt inhibited his insights as a critic.” Paul also cheered Greenblatt’s forthright acknowledgment of Shakespeare’s capacity to “free us from the critical blinders we impose upon ourselves and open our eyes to the deepest truths about human nature” so that “Shakespeare’s freedom can become our own.” Paul applauded Greenblatt’s “tribute” to Shakespeare’s “moral vision” and his simple and straightforward affirmation that Shakespeare was indeed the greatest writer who ever lived and possessed an understanding of the tragedy as well as the comedy of human existence that has gone unsurpassed to this day.

***

Readers of Modern Age may be acquainted with Cantor’s work in the journal’s pages in the two years immediately before his death, 2019 and 2020. Paul was a latecomer to the cultural conservatism espoused in Modern Age. Although he was on cordial terms with conservative colleagues such as the late Peter Augustine Lawler, the previous editor of Modern Age, he long regarded the cultural conservatism espoused by the journal as excessively nostalgic and backward-looking, lacking also any sophisticated understanding of economics. I recall that he had little interest in Russell Kirk, about whose work and life I had written in the pages of this journal (which Kirk founded). Essentially the delay in his embrace of Modern Age as an ally and receptive home for his work owed to the same sort of philosophical differences that libertarians of the right generally felt toward “tradition-minded” conservatives such as T. S. Eliot: they were too Catholic, too insular, too past-oriented.

Although these reservations postponed Paul’s explicit alliance with Modern Age and the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, I must emphasize that he always recognized their shared affinities (and bêtes noires). Ultimately his perception of those affinities won out and he bracketed his economic and political reservations, regarding “traditionalist” conservatives as brothers in arms defending “the permanent things” that Eliot had relentlessly championed—and whose colors Kirk also proudly wore.

Paul’s contributions were few, but readers of Modern Age encountered him at his best, in all of his richness and diversity. For instance, in his 2019 essay on Deadwood, “Milch’s Last Stand,” Paul pronounces the TV series and subsequent movie “tied with Breaking Bad for the title of greatest television show of all time.” In a daring analysis, Paul made his case for the classical stature of “mere television” as an art form and writer-producer David Milch as an artist, elucidating the tragic grandeur of the Deadwood movie’s ending and comparing its elegiac tone to Shakespeare’s Winter’s Tale. Cantor even speculated that the Deadwood TV series might one day be honored—when television comes to be valued as a genre possessing the stature of cinema and theater—as no less a masterpiece than some of the greatest serialized novels of the Victorian era by Dickens, Thackeray, and George Eliot.

Months later, in 2020, Cantor returned to the pages of Modern Age with a review essay on Shakespeare. Here, in what turned out to be his last published word on the Bard, Paul explored Shakespeare’s connections with Greek and Roman antiquity, elaborating on the ideas of his own most recent book, Shakespeare’s Roman Trilogy: The Twilight of the Ancient World (2017). (It was also reviewed in Modern Age that year.)

In these two contributions alone, readers of Modern Age could glimpse the striking range of Paul’s work as a Renaissance scholar and an aficionado of the popular and mass culture of the twenty-first century.

***

[He] loved to parade his art in public . . . [and] virtually never missed an opportunity to appear on stage. . . . He was always confident that he was good at what he did, and for all the signs of personal insecurity in his life, there are almost no signs of creative doubts. When it came to his literary talent, he had no modesty, false or otherwise. He was conscious of just how great he was. . . . Trumpeting his ability . . . , [he] patted himself on the back: “What an amazing man!”

The lines are written by—not about—Paul Cantor. They refer to Charles Dickens, and they appear in a review of Michael Slater’s landmark 2009 biography of “the Inimitable,” as Dickens once dubbed himself. I am reminded of Paul’s sympathetic and perceptive observations about the biography because, at the Cantor memorial in Charlottesville, a classmate of mine observed that Paul was “quite a performer” in his lectures, but “he was no Charles Dickens.” Searching through my own memories of Paul across four decades, however, I must remonstrate that, just as much as Dickens—and uncannily, in oddly similar respects—Paul was “an amazing man.”

He too was “the Inimitable.” Or, as Allen Mendenhall phrased it, commenting on Paul’s work devoted to libertarian economics, he was “the incomparable Cantor.” Having had the good fortune of knowing Paul more than four decades, I can also attest that he possessed an intellectual chutzpah that was quite Dickensian, for Paul too never troubled himself unduly about modesty, genuine or false—nor, for that matter, about diplomacy, remaining ever carefree and unencumbered by scruples that the bracing “Cantor candor” might be misread as boastfulness. “If you can do it, it ain’t braggin’,” Dizzy Dean, the famous St. Louis Cardinals pitcher, hurled back at a sportswriter who accused him of braggadocio. Paul knew the retort and shared the conviction, for he too was “always confident that he was good at what he did.” And “what he did,” above all, was write and lecture. And when the mood struck him: pontificate.

Like Dickens, Paul had his share of personal insecurities and inhibitions. Yet never did I detect a scintilla of self-doubt, let alone stage fright, when it came to intellectual jousting. Not before his one-on-one debate with Richard Rorty. Not in accounts of his spirited exchanges with Allan Bloom and fellow Straussians. Not before getting up to speak in Paris on the same stage as Rorty, Derrida, and other international luminaries. And those examples are just from the early and mid-1980s—long before he entered the public limelight and could stake a claim to share star billing with those names on the basis of his published work.

The point is that Paul didn’t need any external proof, any “basis” in published work. From an early age, Paul was fully “conscious of just how great he was,” as he wrote about Dickens, on cultural matters high and low, whether the topic was Shakespeare’s classic works and classical heritage, Gnostic creation myths in Blake’s Four Zoas and Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound, the (ostensibly unlikely) relevance of Leo Strauss’s concept of esoteric writing to Tom Stoppard’s dramas, the wisdom of market capitalism and the theories of the Austrian School of economics, or television favorites ranging from Gilligan’s Island and The X-Files to Deadwood and Breaking Bad.

All this made him the humanistic Einstein of the twenty-first century, pursuing “semi-seriously,” as he observed in an unpublished memoir, his grand “Unified Field Theory of Culture.” The Einstein allusion was meant to be jocular, but it was no joke that Paul took a huge swath of humanistic learning as his province, and sought to integrate it and extend it in bold new directions. Paul never won a MacArthur “Genius Grant.” Yet he was preternaturally gifted, with more than a touch of genius—and in saying that I weigh my words carefully. I am not joking when I say that Paul could have effortlessly taught Ph.D. seminars and become a leading figure in any number of fields: comparative literature, intellectual history, art history, political philosophy, musicology, macroeconomics, and more. It was more or less an accident that he wound up in the field of English literature, and I count it my great good fortune that Fate or happenstance landed him there.

It was a humbling as well as inspiring—and always edifying—experience to listen to Paul Cantor, the maestro and the mensch. In addition to my informal six-hour “tutorials” in his condo, I attended at least a half dozen courses that he taught in the 1980s at the University of Virginia. It didn’t matter whether I was a first-year grad student or a faculty colleague: I learned enormously from Paul, whether the courses were listed as undergraduate or graduate. That didn’t matter either way—he lectured spectacularly in both settings. What I learned were not just his arresting interpretations of classic works of poetry and fiction and drama, but also how to think about literature, culture, and history. Paul displayed an incredible talent of remaining always accessible to the beginning student and always challenging and thought-provoking to the advanced student. Indeed, to know Paul Cantor was also to learn about the scale of intellectual capacity and achievement. The lines of the Roman poet Lucretius in The Nature of Things come to mind:

A fair-sized stream seems vast to one who until then

has never seen a greater.

So with trees, with men:

In every field each man regards as vast in size

The greatest objects to have come before his eyes.

When listening in his living room to Paul, holding forth on subjects of all kinds,

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken,

as Keats wrote in “On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer.” Paul represented a new and much greater “object”—of “vast” proportions—than I had encountered in my Irish immigrant enclave and Christian Brothers’ education. That is to say, encountering Paul meant entering a larger world. It meant stepping up to a much higher level, like an athlete placed on the same starting line near the Olympic contenders, the world-class performers. Getting to know Paul “up close”—no other senior professor of my acquaintance granted students such privileged access—confronted me with a “big league” scale of intellectual talent and performance.

Here I must also add that, conscious as he was about what “greatness” entailed, academic status and intellectual reputation themselves neither impressed nor intimidated Paul. What mattered alone was the quality of mind before him, manifested in the written work or the dramatic performance. Certainly Paul respected the evaluations of others. Yet no one else’s opinion could ever substitute for his own sovereign, independent judgment, governed by his own criteria.

Had Cantor done nothing more than his pioneering studies of Shakespeare and the English Romantics, he would still have been one of the superior American literary critics of our time. His public turn to television, wrestling, Straussian philosophy, libertarian politics, and Austrian economic theory showed, however, that even the immense and challenging fields of Renaissance and Romantic studies were not sufficiently capacious to satisfy his wide-ranging mind.

Despite his move toward popular culture criticism, Paul did not cease to write, and especially to lecture, about the literary canon and the magnificence of the classics, starting with Shakespeare. He took every opportunity to champion “the permanent things” and to trumpet the Arnoldian summons to honor “the best which has been thought and said in the world”: great literature, in the broadest, most democratic sense of that word. Although Paul came increasingly to emphasize the wondrous intricacies of the “art market” and to ponder the relationship between culture and economics, he never ceased to defend aesthetic value as a criterion of literary excellence. He always sought to restore interest in and respect for the majestic achievements of the human imagination, starting with Shakespeare’s dramas, and to communicate their riches not just to colleagues but also to general readers.

Already a great teacher, he became an indispensable public educator: an aristocrat of the intellect who welcomed everyone to join him in the company of the elite creators of the ages. Ultimately if ironically, it may be the case that this form of democratic pedagogy—exemplified in his absorbingly readable publications as well as in numerous videos and online interviews—is the accomplishment for which Paul Cantor is best remembered.

John Rodden’s most recent book is The Intellectual Species: Evolution or Extinction?