The aim of conservatives for some time now has been to resist what C. S. Lewis called “the abolition of man.” One effort at that abolition was communist ideology, another is the therapeutic pragmatism of Richard Rorty and others.1 But the most dangerous threat today comes from the science of biology. Denial of human distinctiveness is increasingly rooted in the homogenous materialism of evolutionary biology. And advances in biotechnology are providing the means to destroy what is qualitatively different about our species.2 Especially troubling is the uncritical acceptance of biological reductionism by writers often called conservative. Here I use Walker Percy’s defense of the goodness and mystery of the human being to expose the misanthropic implications of this reductionism in the influential writing of the “neoconservative” Francis Fukuyama. I present this effort as an example of what conservatives should be doing as the twenty-first century begins.

The philosopher-novelist Walker Percy says, contrary to modern thought, that the human being is by nature an alien.3 People, he adds, feel more like aliens than ever. Modern science has made great progress explaining everything but the human self and soul. Scientific experts tell people that they are fundamentally no different from the other animals, and so they should be happy in a world where lives are more free, prosperous, and secure than ever before. Their feelings of homelessness are either basically irrational or merely physiological. They can be cured through a change in environment, soothing therapeutic or ideological platitudes, or the right mix of chemicals.

The experts are evil, Percy contends, because they want to deprive human beings of their distinctive humanity, of their longings that point them beyond the satisfactions of this world and toward each other, the truth, and God. Their efforts may never completely succeed, but allegedly wise experts—from communist tyrants to therapeutic psychotherapists—have destroyed or needlessly diminished a huge number of human beings. The experts claim, in part, to be motivated by compassion. They want to provide the freedom from misery that the Christian God promised but could not produce in this world. The compassion they claim to feel for others they really feel for themselves. They, too, are aliens, and they want to free themselves from their trouble. They think that by reducing others to comprehensible or simply biological beings they can raise themselves to something like angels. They seek to be at home not in the world of human beings but through its complete transcendence. The world they have created is for angels and pigs, for theorists and consumers, not for human beings.

For Percy the best human life is to be at home with one’s homelessness or alienation, and so to be free to enjoy the good things of the world in consciousness of their limitations. This life is easier for Christians, who have an explanation for why the human being feels like an alien in this world. But it does not necessarily depend on religious belief. It is available to one who can tell the truth about one’s self and live well in acceptance of it. We are born to trouble, and doomed to failure and death. But we have compensations in the joyful sharing of what we can know with others, and in the love of one human being, one self-conscious mortal, for another. And those human goods are only given to aliens, to the beings with language, who can explain everything but themselves. Percy would restore the Socratic or psyche-iatric tradition against psychotherapy. People can be happier as human beings not through platitudes or drugs but through the search for the truth about their extraordinary natures.

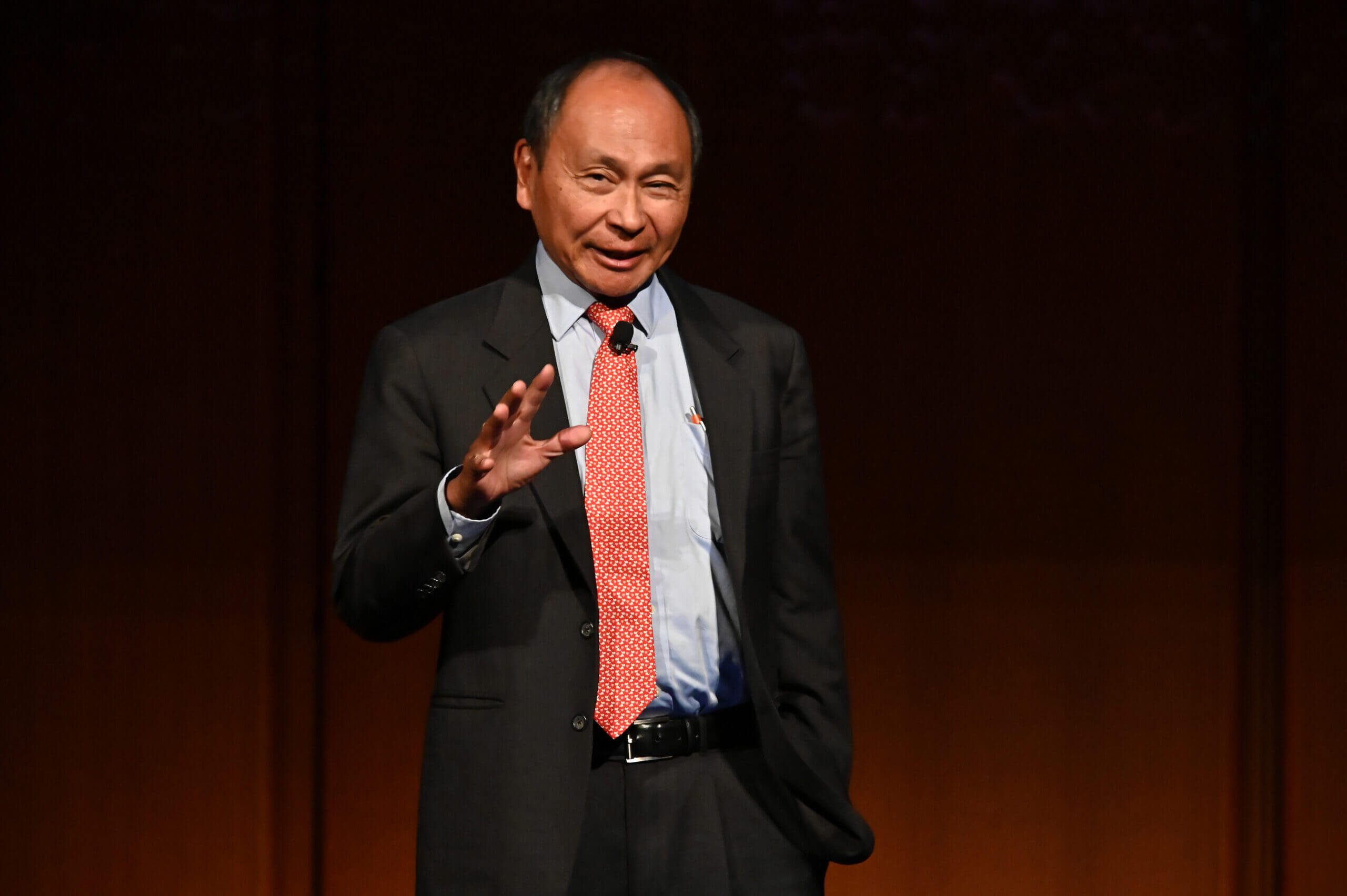

From Percy’s perspective, a leading American teacher of evil over the last decade has been Francis Fukuyama. Fukuyama’s writing is more insidious than that of the largely discredited socialists and reductionistic scientists. He claims to be a defender of human liberty and dignity, as well as of the superiority of American liberal democracy to other political orders. Many of his policy recommendations and philosophical preferences seem conservative, and he seems to flourish in neoconservative circles. He has written two very comprehensive and at first glance contradictory best-sellers. The first, The End of History and the Last Man, took seriously the possibility that history had ended with the end of the cold war, and that the only credible regime left in the world is liberal democracy.4 It seemed a lullaby calculated to make Americans and the world satisfied or at home with America’s undeniably great victory. His current hit, The Great Disruption, claims to show that nature triumphs over efforts at human or historical transformation.5 Human beings are social and rational beings by nature, and their natural instincts lead them to replace depleted social capital. This book, too, seems a lullaby, but calculated to make Americans and the world satisfied with the compatibility between the contemporary view of morality and justice and their longings for community. It turns out that the human longings for love, the truth, and God are not natural at all.

Fukuyama’s thoughts on history’s end, he acknowledges, are indebted to the great Hegelian Alexandre Kojéve, the semisecret founder of postmodernism.6 Kojéve claims to understand even better than Hegel himself that the end of history would have to be the end of human distinctiveness or liberty. Everything, for Kojéve, depends on the distinction between nature and history. Nature is what is determined by impersonal, rational laws. But human beings are distinguished by being free or historical. They alone can act to negate nature and transform themselves over time. They are temporal beings because they are self-conscious mortals. So human wisdom is a complete articulation of all that is implied in being a mortal. Every human life has a beginning and an end. History itself must have a beginning and an end. Only at history’s end can one be certain that human existence is essentially historical. That certainty, and the radical atheism it includes, is Kojéve’s alleged wisdom.

Specifically human desire, Kojéve contends, is the desire to be recognized as free by another free being. It is the desire to be definitively free from one’s natural dependence or finitude. Human beings act in response to that dissatisfaction, and that action is history. At the end of history, human beings are seen by each other as equally free or equally historical beings. They also see that the free being, the one who can act, must die. The recognition of human freedom, paradoxically, must be the recognition of human finitude. Kojéve implies that political recognition is finally insufficient compensation for death, and so the misery connected with death overwhelms the satisfaction that comes from being a free and equal citizen. At the end of history, death, or the being who dies, must be put to death. The lesson of history is that history was an error.

Kojéve’s radical observation is that the liberal and the socialist societies in our century both recognize the equal freedom of all human beings as citizens and both are devoted to putting death to death. Freed from illusions about nature and God and understanding the historical being as an error, they are aiming to complete the reanimalization of man they have accepted in principle. No moral resistance to the technological effort to extinguish human liberty and thus make human beings, like the other animals, completely at home in nature can be effective. The moral principles that might support such resistance have been authoritatively discredited by history.

For Kojéve everything depends on whether humans are essentially historical or natural beings. He claims to have evidence that they are historical, and that human liberty has no future. He might be called a teacher of evil insofar as he promotes a life without good and evil. Much of his writing was to show the futility of resistance to the destruction of what may remain of human liberty. But Kojéve, at least in his later writing, claims to write description, not ethics. He merely chronicles the record of human self-destruction. Human beings cannot choose whether or not to be like the other animals again. The alien or stranger in the cosmos, the historical being, has disappeared. Far from being a cosmic catastrophe, that disappearance is good for nature; the cosmos is really a cosmos once again.

Instead of presenting the choice between nature and history plainly, Fukuyama makes the incoherent claim that at the end of history the reigning form of government is completely satisfying to human nature. He employs the Socratic, tripartite account of the soul to show that liberal democracy satisfies human desire, human spiritedness, and human reason. Human beings may now be satisfied or completely unalienated as human beings. Religion, according to Fukuyama, withers away under liberalism. There is no need for otherworldly longing if this world is lacking in nothing.

He pays lip service to the Nietzschean fear that the world at history’s end might be filled with contemptible last men, but he does not really think that contemporary Americans are subhuman beings. With his confusing mixture of human nature and history, Fukuyama is far more pernicious than the openly misanthropic Kojéve. The death of God, Kojéve rightly says, must be the death of man. But for Fukuyama human beings can continue to be human at history’s end without God. He gives human beings no reason to resist the idea of history’s end.

The Great Disruption, Fukuyama’s new book, seems at first glance to choose human nature over history. He opens with the famous quote from Horace about the foolishness of human efforts to throw out nature with a pitchfork. Nature “always comes running back,” triumphing over history and technology, and not the other way around.7 Fukuyama now seems to perceive that he was confused when he considered seriously the possibility that history might end, and he makes no such claim, at least explicitly, in this book.

Fukuyama perceives that the distinction between nature and history of Hegel, Marx, and Kojéve really came from Rousseau. For Rousseau the natural human being is asocial, stupid, and wholly determined or unconscious. And so human reason and sociality are nothing but historical constructions. This state-of-nature premise, in truth, is the foundation of all modern individualism, including classical liberalism or libertarianism. The individual has no natural inclination for society, and he cooperates with others only as a means for achieving his individual or natural ends. Fukuyama observes that recent “primatological research is revealing because it shows us that a great deal of social behavior is not learned but is part of the genetic inheritance of both man and his great ape forebears.”8 If historical man evolved from the apes, as Rousseau thought, then we now know that natural man is a social being. Natural sociality, and not free human construction, is the main source of social and political life.

Rousseau wrongly thought that natural man was healthy and content because he was solitary and self-sufficient. At history’s end, Kojéve concluded on the basis of this Rousseauean foundation, human beings must return to that radically individualistic existence. But all the evidence we now have shows that they are gregarious by nature, and that isolation or excessive individualism is pathological. The human animal cannot be content alone. All we now know about hunter-gatherer and prehistorical societies, not to mention what we now know about our close evolutionary relatives, the chimps, shows that Rousseau was also wrong to contend that natural man was more peaceful than allegedly late-historical beings. Those societies long past were at least as violent as recent human society.9 The aggressiveness and status-orientation of the chimps even suggest that there is no specifically human quality that makes human beings more bellicose than other species. The competition among the chimps to be alpha male Fukuyama understands as at least incipiently political, contradicting Kojéve’s view that the desire for recognition is distinctively human or historical.

He sees the breakdown in social life in recent decades to be pathological but temporary. The disruption caused by the technological movement from an industrial to an information-based economy and especially by the invention of the birth-control pill is now in the process of being repaired by human reform rooted in the persistence of social human nature. Human beings desire social stability and communal belonging. So they naturally or spontaneously create social rules. The libertarian spontaneous order literature, according to Fukuyama, correctly argues that human beings will produce order if left to their own devices, and that order will be small scale or decentralized.10

Fukuyama endorses most recent conservative reforms in opposition to policies in the 1960s that combined permissive individualism with big, centralized government. Yet he opposes, most of all, conservative critics of capitalism or liberalism. “Social capital,” he asserts, “is not . . . a rare cultural treasure passed down across the generations—something that, if lost, can never again be regained.”11 Because it is rooted in nature, “It is not something with a fixed supply that is now being remorselessly depleted by us modern, secular people.”12 Nature cannot be cast out by misguided human projects, and so modern society does not depend on the premodern inheritances of religion, family, and political community. Each of those institutions has a natural, or not merely historical or traditional, foundation, and so each is bound to reappear in some form or another.

The good news is that we can look to the future without seeking authoritative guidance from the past, and we are free to reject those aspects of the past that seem irrational or unnatural. Rationalism does not lead naturally to individualism or unconstrained permissiveness, because the rational being by nature is also a social one. Reason properly understood is a tool for a human being to fulfill his natural and largely social longings. Fukuyama agrees with Burke that “reason is insufficient to create the moral constraints needed to hold societies together.” No rational-choice theorist can ever account for the emotional or social dimension to human choice, and so those theorists misunderstand how human beings employ reason. Fukuyama rejects the “relativistic element to Burkean conservatism,” which comes from a lack of confidence in natural sociality.13

His confidence comes from the life sciences, and so he finds the foundation of human stability in the fact of natural evolution. Human beings are “born with preexisting cognitive structures . . . that lead them naturally into society.”14 But these “hard-wired’’ structures did not always exist.15 The coming-into-existence of all human characteristics can be explained by the requirements of the species’s adaptation to its environment. Contrary to individualistic philosophers such as Hobbes and Locke, Fukuyama says that evolution can be explained more in terms of species than individual preservation, although both are important motivations of behavior. So humans are partly social and partly self-interested beings, and sociological and economic explanations of human behavior are both partly correct, but not for the reasons the social scientists give.16

Fukuyama notices that the size of the human brain has tripled during the time that the human line of evolution separated from that of the chimpanzees. And he admits that the evolutionary explanations for that rapid, unprecedented growth are only speculative, but he seems certain that some such story must be true. He knows that the development of the neocortex gave human beings seemingly unique qualities like complex language, consciousness, religion, and culture, but they too exist as means for evolutionary or essentially physiological ends.17 He refuses to join Kojéve in considering the possibility that the capacities for language and consciousness are inexplicable cosmic accidents that must be accounted for historically, not naturally. Nor does the possibility of an inexplicable discontinuity within nature itself open him to the possibility of the truth of biblical revelation. For Percy the refusal to consider that possibility is the characteristic dogma of life scientists.

Fukuyama dismisses as unrealistic the libertarian dream in which coercive, hierarchical political life will completely wither away, to be replaced by wholly spontaneous and efficient social cooperation. Human beings will remain to some extent political or status-seeking beings. Like the chimps, by nature they just like organizing themselves into hierarchies.18 And history has shown that political coercion or formal legal authority and war have been required to extend the scope of human cooperation and social order. It overcame the selfish, irrational desire of social animals to perform as members of their own small groups. It is naïve, for example, to believe that American slavery would have evolved out of existence because it is inefficient.19

Human beings have gone much further than the other animals in organizing their whole species hierarchically. They have moved from families to tribes to political communities. They have done so, in part, because they naturally desire to rule and receive recognition, and their brains allow them to use reason much more efficiently to satisfy this desire the chimps. Fukuyama surely, if perhaps accidentally, calls attention to a tension in human desire. Our social natures point in the direction of the communal belonging and selfishness of small, tightly knit groups.20 But our political natures point to large and finally universal or universalistic states. The mixture of reason and the natural desire for recognition might be understood to disrupt the natural bonding with families and friends. But that apparently fundamental natural tension is not one of Fukuyama’s themes. He does not present the great disruption of our time in terms of contradictory tendencies in human nature, even if he does admit “that the progress of capitalism simultaneously improves and injures moral behavior.”21

Near the end of his book, Fukuyama actually acknowledges, although not consistently and surely contrary to Horace, that human moral progress is not rooted in nature at all. Human beings conceived of the idea of moral universalism, based on the recognition of the capacity of each human being for moral choice. Life scientists, of course, do not explain human thought or behavior that way; Fukuyama’s mode of expression suddenly and unexpectedly becomes Kantian or Hegelian. Human beings have the freedom to negate nature on behalf of rational idealism. They, alone among the animals, can establish their autonomy or freedom from nature. Human beings have rights, Fukuyama strongly suggests, because they are free beings, not because they are natural ones. The “principle of universal recognition” links together the Declaration of Independence, Kant, Hegel, “the Universal Declaration of Rights, and the rights enumerated in the laws of virtually all contemporary liberal democracies today.”22 The elites in liberal democracies today do not understand rights to be rooted in nature. And all human experience except that of the modern West is that social beings do not understand themselves as beings with rights.

Fukuyama does make a rather lame effort in one place to reduce moral universalism to a rational tool for self-preservation. He announces that the Enlightenment discovered that all traditional sources of community were irrational, because they led to social conflict internally and war with other communities externally. Moral universalism leads to a peaceful domestic and international order. Fukuyama adds the astounding assertion that “The great moral conflicts of our time have arisen over the tendency of human communities to define themselves narrowly on the basis of religion, ethnicity, or some other arbitrary characteristic, and to fight it out with other, differently defined communities.”23 That might explain National Socialism to some limited extent, although surely not the Holocaust, or the conflicts in Northern Ireland and in the former Yugoslavia. But it does not account at all for the cold war, which was a competition between two forms of universalism. Nor does it account for the perhaps a hundred million people killed on behalf of communist ideology in this century. Religion and ethnicity, all things considered, have been nowhere near the most murderous motivations of our time. On the moral evolution from war to peace on the basis of self-preservation or fear of the consequences of high-tech war, Fukuyama shares the naïveté of Kant and his disciple Woodrow Wilson. But they had the excuse of not having the benefit of post–World War I experience.

Fukuyama becomes even more confusing when he observes that moral universalism actually originated with religion and was only later secularized or politicized. He does not explain why or even if human beings are religious beings by nature. Following the lead of the life sciences, he does not think that consciousness or any other human quality is the source of longings which point beyond the natural world. He also seems to accept Kojéve’s Hegelian or historical view of religion. Human beings, dissatisfied with their inability to satisfy their desire for recognition in this world, imaginatively create another one where it is satisfied. That imaginary construction becomes a project for historical or political reform. Fukuyama writes that the Christian principle of the universality of human dignity was “brought down from the heavens and turned into a secular doctrine of universal human equality by the Enlightenment.”24

The political effort of the modern West has been to achieve in this world what the Christian God achieved only in heaven. In other words, “the business of building higher-order hierarchies was taken away from religion and given to the state.”25 The shared values of human beings used to be religious, now they are political. At one time Americans might have regarded their nation as essentially Christian, but now only a small and suspicious minority do so.

The separation of religion from “state power,” Fukuyama contends, was the cause of its “long-term decline” in “the developed world.”26 This decline is beneficial and irreversible. He dismisses the hope of some conservatives and the fear of many liberals that “moral decline” might be stemmed “by a large-scale return to religious orthodoxy, a Western version of Ayatollah Khomenei returning to Iran on an airliner.” His identification of orthodoxy with the fanatical Khomenei rather than Orthodox Judaism or John Paul II shows that he believes that God is dead. He has been killed by history. Sophisticated people now associate orthodox belief with unreasonable moral and political repression, which apparently is evidence that there is no natural foundation for such hierarchical belief. Fukuyama emphatically does not praise the countercultural role small orthodox communities have played in filling the moral vacuum caused by the temporary depletion of social capital. And that is because “we . . . are not so bereft of innate moral resources that we need to wait for a messiah to save us.”27

The closest Fukuyama comes to praise of religious orthodoxy is his presentation of Farrakhan’s Islamic Nationalist Million Man March and the “conservative Christian” Promise Keepers as evidence that “something was amiss in the expectations society had of men, and that men had of themselves.” But he soon dismisses those groups as “highly suspect” to liberal, democratic, and morally universalistic Americans.28 The subordination of women discredits the Promise Keepers, whereas it is anti-Semitism for the Nation of Islam. Treating the two groups as immoral equivalents shows how promiscuous Fukuyama’s disdain for orthodoxy and religious hierarchy is. The return to orthodoxy or the sanctity of marriage cannot be the way to restore paternal or parental responsibility. That would seem to be especially bad news for fatherhood, and Fukuyama quietly accepts and affirms that troubling conclusion.

He notices that the family is coming back in reaction against the social disruption caused by its near collapse. But the end of disruption will be no mere restoration. People will not return to the old, largely religious, norms concerning sex, reproduction, and family life. The new technological and economic conditions have made strict “Victorian values” obsolete.

After all, “no one is about to propose making birth control illegal or reversing the movement of women into the workplace.” And if “unregulated sex” no longer leads to pregnancy, and having a child out of wedlock no longer leads to “destitution,” then why have legal or moral sexual rules at all? So “the stability of nuclear families is likely never to recover,” and “kinship as a source of social connectedness will probably continue to decline.” Parents, mindful of “their children’s long-term life chances,” will continue to have fewer of them.29

Fukuyama seems to welcome a world full of promiscuous, prosperous, but never lonely single mothers. Technology, contrary to the general thrust of Fukuyama’s pitchfork argument, has changed the nature of women by dissociating sex from reproduction, and so also the more culturally created role of the man as father. The life scientists regard the relationship between mother and child as strongly natural, but that of father and child as only very weakly so. Men are so naturally promiscuous that women have to trick them into being faithful husbands and fathers.

Now it is no longer worth the trouble. Fathers are free to live naturally or promiscuously without guilt, legal responsibility, or social stigma. Fukuyama criticizes the therapeutic platitude that children grow up just as well in a single-parent than in a two-parent family, but he also makes clear that we better hope that the therapists are not all that wrong.30 The new family in the new society will be nothing like that traditionally supported by hierarchical religion.

But religion has not quite withered away. Fukuyama notices a return to “primitive,” decentralized, and merely instrumental religion. Although no religion has ever understood itself as merely instrumental, people now do so. It has become merely a “convenient” and “rational” support for our desires for social belonging and social rules. This new religion is not some civil theology, because the thoroughly secularized moral universalism of the political realm is quite able to stand alone. It is merely social theology, generated by the various forms of spontaneous order.31

We are tempted to say that today’s “benign” religion assists in repairing the damage done to social life by orthodox religion.32 But from a merely natural perspective, how orthodox religion came to oppose spontaneous, decentralized order with moral universalism remains a mystery. People today are more enlightened because they are conscious that religion should serve their natural inclinations. Free from hierarchical, orthodox fanaticism, they feel more at home as natural beings. But religion could not have achieved the goal of moral universalism had it been viewed as merely instrumental. Our knowledge of ourselves as merely natural, social beings must have been a product of historical development, and it has brought the morality-altering and historically transformative role of religion to an end. In a loose way, Fukuyama is in greater agreement with Kojéve in The Great Disruption than he was in The End of History. He points to the conclusion that history has come to an end, and the result is that humans are merely natural beings again.

Fukuyama also seems to agree with the American professor of philosophy Richard Rorty, who says that Americans have come to prefer comfort to truth, because they now know they are not, by nature, inclined to know the truth. People, Fukuyama explains, “will repeat the ancient prayers and reenact age-old rituals not because they were handed down by God, but because they want their children to have proper values and want to enjoy the comfort of ritual and the sense of shared experience it brings.”33 Skipping over the question of whether proper values can really include unregulated sex, we must wonder whether the comfort and sharing can be enjoyed by human beings without any concern for God and truth.

The return of religion without hierarchy or God is part of a package for social restoration that, according to Fukuyama, includes the celebration of national independence day, “dressing up in traditional ethnic garb” and “read[ing] the classics of their own cultural tradition.”34 Today’s priests, rabbis, and ministers, to recall an old joke, are all dressed up with nowhere to go. The form, not the content, is what binds us to the past and each other. Kojéve said at one point that post-historical beings can still remain snobs; our ability to perpetuate the meaningless forms of the past for their own sake still might separate us from the other animals. Perhaps Jewish and Christian sacred services have become no different from Japanese tea ceremonies. But Fukuyama’s instrumental traditionalists are not snobs, a term that sounds too prideful and hierarchical and not comforting enough.

I am not going to dwell on the fact that the principles of the American Declaration of Independence claim not to be traditional but true, and that Fukuyama’s affirmation of moral universalism is in some way an affirmation of their truth. Yet I must mention that the most successful effort to revive the reading of the classic texts of the Western tradition in our time, the one inaugurated by Leo Strauss, was inspired by the pursuit of truth, not comfort, as Fukuyama well knows. I must add that those religious sects which claim to speak truthfully and with authority about a living, loving God are the ones that are flourishing, and that those that believe in the authentic sanctity of marriage and the family are the ones with the best value-laden programs for children. Those that consciously claim to provide nothing but a comfortable, communal experience tend to languish.

Fukuyama has confused us beyond belief about whether human beings crave hierarchical authority by nature, or whether that chimp-like quality has been eroded almost beyond recognition by free, historical progress. It is another thing altogether to say that human beings do not long to know the truth about God and the fate of their souls, that they are not, in their self-conscious perception of their incompleteness and their mortality, in some way open to the divine. And it is another thing still to say that love and anything resembling marriage are compatible with unregulated sex. But Fukuyama is not particularly concerned with the intimate, personal union between man and woman, the love of one human being for another, but only with properly providing for the raising of children.

The key difference between Percy and Fukuyama on evolution is that Percy holds that the development of the neocortex and that capability made human beings qualitatively distinct from the other animals. They became self-conscious beings, who are defined by love—including love of each other, God, the truth—and death. Percy understood what we know about evolution in light of the long Western tradition that human beings are tormented by nature by a longing for immortality, and that they have excellences, perversities, and a capacity for both good and evil not given to the other animals. There are responsibilities given by nature to human beings that are shared neither by angels nor by chimps.

Part of the lullaby of Fukuyama’s or the dominant view of evolutionary biology is that species survival, not personal survival, is the major source of our longings. We are only moved unconsciously, by instincts no different in kind from those of the other animals. As Fukuyama explains, “throughout the natural [including human] world, order is created by the blind, irrational processes of natural selection.35 One of Fukuyama’s teachers, Allan Bloom, also said that human beings are defined by love and death, and that the capacity to be moved by them is fading in sophisticated America today. So Fukuyama ought to know what is conspicuous by its absence in his analysis of human nature. He says virtually nothing about the experience of self-consciousness and the love of one conscious being for another. For Fukuyama human eros appears not to be polymorphous, nor does human perversity. His final position, hidden under a mountain of confusion, may be that homogeneous or reductionistic explanations of evolutionary biology become more true as an account of human thought and action as human self-consciousness or history recedes.

His suggestion that love and death might disappear or almost disappear is more perplexing than Kojéve’s. Consciousness of death, the intractable natural limitation, would seem, on his account, to be natural. What Kojéve and Rousseau regard as historical acquisitions, he views as the product of human nature. So somehow he must contend that human beings are not shaped or moved much by what they really know by nature. Human perversity, Fukuyama suggests, has evolved out of existence, because the human being no longer wrongly understands himself as an alien, as more than a natural being. In this respect, Kojéve would have observed, Fukuyama writes as a pragmatist, one who vulgarly or fearfully refuses to speak of the truth of existentialism, of the being who is dissatisfied because he knows he will die. But surely nobody really believes that an evolutionary and homogeneous account of human experience and behavior explains everything people do.

Fukuyama’s most coherent but still quite questionable claim is that history progresses but nature is cyclical.36 His real criticism of Kojève is that human beings cannot return to being stupid, asocial animals because that is not what they are like by nature. They have social, but not spiritual and only minimally political, needs that must be satisfied. So political life, the family, and religion can be reconstituted in ways compatible with our historical achievement of moral universalism. On this point, Fukuyama is also more realistic than his fellow pragmatist Rorty. Rorty writes as if all human experience is the product of description and redescription. Everything human is a linguistic creation; people are not limited or directed by nature at all. Rorty writes as if religion, the family, and perhaps even the state could just be talked out of existence, and he views all social life as merely an instrument for the enjoyment of private fantasies. Rorty also says that human beings are coming to define themselves, in Darwinian fashion, as clever animals and nothing more. They have decided to surrender their cruelty-producing illusions concerning theology and metaphysics. On this point, Rorty seems more realistic or honest than Fukuyama. They both define man as merely a clever (social) animal, but Fukuyama does not present that definition as Rorty does, as morally inspired propaganda.

The social beings of the great restoration will have no point of view by which to resist or be alienated from social and political life. They will long for community and social stability, and not have any moral or religious principles by which to criticize their community. Such a principled point of view, coming from the natural openness of human beings to a morally relevant order of Being, allowed the dissidents Solzhenitsyn and Havel to resist communist tyranny, but perhaps the need for such resistance has become obsolete. Hierarchical narrowness and conflict, Fukuyama believes, has little future. Evil, either having no natural foundation or having been overcome by history or both, has disappeared from the world. Human nature is basically good, and there is every reason to believe that it will perpetuate itself.

In an article in the National Interest presenting his “Second Thoughts” on history’s end published almost simultaneously with The Great Disruption, Fukuyama announces that human nature “definitely”has no future.37 He also says that he was wrong to say that history could end, because, in his mind, that end implies a natural standard by which we can say human beings are satisfied. Socialism was defeated by human nature. But what if human beings can consciously and fundamentally alter their natures technologically? What if they can decide—not through political action or linguistic propaganda but through scientific manipulation—to become something else? For today, Fukuyama’s analysis of human nature in his books remains mostly relevant. But as for tomorrow: “To the extent that nature is something given to us not by God or by our evolutionary inheritance, but by human artifice, then we enter into God’s own realm with all of the frightening powers for good and evil that such an entry implies.”38

In The Great Disruption Fukuyama reduced human beings to clever, social animals, but in “Second Thoughts” he says they are on the way to becoming gods. The twenty-first century, he predicts, will be the century of biology.39 His Great Disruption aspires to be the definitive biological or socio-biological treatise of that century’s beginning. There he celebrates nature’s victory over human manipulation. Now (and this is an amazing contradiction) he says that we are on the verge of a biology-based conquest of nature that makes all previous human efforts look like nothing. First of all, biologists are about to bring the genetics of aging under human control, and soon human beings will live for hundreds of years, with no certain limit on life expectancy. More importantly, biotechnology will soon be able to alter the functioning of human beings in ways that affect not only the individual treated, but “all subsequent descendants of that individual.” What the Communists and Nazis failed to do politically the scientists may soon accomplish technologically: They will create “a new type of human being,” one not at all determined by natural inclinations beyond human control.40

The first efforts at genetic manipulation will be to eliminate disease and obvious physiological disorders, and it will be difficult to quarrel with the results. But soon the efforts will extend to the eradication of dwarfism and then mere shortness. And then scientists will address human personality characteristics deemed undesirable, if not exactly unhealthy. Men are more violent and aggressive than women, and their genes as much as their environment point them in the direction of prison. So why not eliminate the distinctively male qualities? Fukuyama himself had gone a long way in The Great Disruption toward the conclusion that they have become superfluous. A well-ordered person is one with no propensity for violence, no desire to strike out against others or his community. Biotechnology will bring cruelty to an end. Fukuyama cautions that there must be discussion about “what constitutes health,” but he gives no argument for the goodness of the male spirit of resistance.41 Perhaps science can correct certain residual aberrations of evolution in the general spirit of evolution’s intent.

The prelude to the biotechnological determination of the future are the successes of neuropharmacology or drug therapy. Ritalin and Prozac are powerful, widely used drugs that have fundamentally changed human behavior. They have helped those who are severely disruptive or depressed. But Ritalin is also routinely given to boys “characterized simply as high spirits.” And Prozac calms nervous women through chemically produced feelings of self-esteem. By taking the edge off being either a man or a woman, the drugs “move us imperceptibly toward the kind of androgynous human being that has been the egalitarian goal of contemporary sexual politics.”42

Everyone will become the same, well-ordered according to our egalitarian ideal. Biotechnology can do a better job than nature herself in making us perfectly social beings at home in the world. The distinction between male and female has always been alienating and confusing. What is wrong with doing away with it? Fukuyama “wonders what the careers of tormented geniuses like Blaise Pascal or Nietzsche himself would have looked like had they been born to American parents and had Ritalin and Prozac available to them at an early age.”43 They would have been untormented! True, their torment was intertwined with their ability to know much of the truth about being and human being, and to be haunted and deepened spiritually by God’s hiddenness or death. But according to evolutionary biology, human beings are not fitted by nature to know the truth, and its fanatical pursuit by tormented geniuses has not been good for the species. Fukuyama’s suggestion in The Great Disruption is that the world is better off without such men, who prefer truth to the comfort of social belonging, who had with special intensity the disquieting experience of being aliens. He observes that the alleviation of depression by psychoanalysis, or telling the truth to oneself about oneself with the help of another, has been replaced by psychotherapy, or the chemical management of symptoms. The latter, of course, works much better.

Fukuyama has little hope that human beings will be able to resist biotechnology on behalf of God, nature, or just manliness or womanliness. There are two global revolutions going on, in information technology and in biotechnology. According to Fukuyama, the information revolution has had leveling, libertarian, and beneficial effects. There is an attempt by nonscientists to regulate biotechnology morally, but soon the “libertarian mindset” of the market-defined and morally universalized world will brush such moral concerns as “uninformed prejudice.”44

He cannot help but conclude that “within the next couple of generations we will have the knowledge and technologies that will allow us to accomplish what the social engineers of the past failed to do. At that point, we will have definitively finished Human History because we will have abolished human beings as such. And then, a new, posthuman history will begin.”45 But posthuman history is qualitatively different from human history. And so Fukuyama, in spite of himself, finally explains how human history will end. Human beings will drug out of existence everything that makes them miserable—love, death, anxiety, spiritedness, depression. They will live for hundreds of years, but they will not care all that much about the lengthening lifespan. Death will mean little or nothing to them. It goes without saying that science cannot actually eradicate the fact of death, but perhaps it can keep death from distorting or defining what otherwise would be healthy human life. Human beings will become fundamentally no different, except perhaps less spirited or aggressive and so less gregarious, than other gregarious animals.

Contrary to his liberal intention, Fukuyama is a teacher of evil because the people he describes in The Great Disruption have no motivation, no reason to resist the impending evil he describes in “Second Thoughts,” an evil potentially far worse than the Holocaust or the Gulag. Those who prefer comfort to truth and are rationally or skeptically distrustful of all hierarchies will swallow pills and submit to operations for their obvious social and survival values. Fukuyama is a teacher of evil because he has not really asked the questions Percy does in The Thanatos Syndrome, a novel just a bit ahead of its time about a scientific project with political support to use chemicals to suppress human self-consciousness. Why is the surrender of self-consciousness bad for human beings? Why does it diminish them? Why does it enslave them to experts, self-proclaimed gods, who exempt themselves from the treatment they impose on others? Why does the effort to eliminate all human disorder and suffering in the name of health lead to projects for the extermination of large numbers of human beings? Why is it better to be a dislocated or alienated human being than a contented chimp? And yet, why, in the end, are the attempts to alter nature and to replace God doomed to failure?

Peter Augustine Lawler (1951–2017) was Professor of Political Science at Berry College, Georgia, and served as editor of Modern Age shortly before his death.

- For the details supporting the comments on Rorty made in this article, see my “The Therapeutic Threat to Human Liberty: Pragmatism and Conservatism on America and the West Today,” Vital Remnants, ed. G. Gregg (Wilmington, Del., 1999) and Postmodernism Rightly Understood: The Return to Realism in American Thought (Lanham, Md., 1999), chapter 2. ↩︎

- For the latest and a particularly eloquent and comprehensive statement concerning the danger to human liberty and dignity of the contemporary interdependence of biological rhetoric and biotechnology, see Leon R. Kass, “The Moral Meaning of Genetic Technology,” Commentary, Vol. 108 (September 1999), 32-38. ↩︎

- This summary of Percy’s thought presented here is based primarily on his Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book (New York, 1983) and The Thanatos Syndrome (New York, 1987). For more details, see my Postmodernism Rightly Understood, chapters 3 and 4. ↩︎

- Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and The Last Man (New York, 1992). ↩︎

- Francis Fukuyama, The Great Disruption: Human Nature and the Reconstitution of Social Order (New York, 1999). ↩︎

- For more on Fukuyama’s confused debt to Kojéve, see my Postmodernism Rightly Understood, chapter 1. ↩︎

- Fukuyama, The Great Disruption, vii. ↩︎

- Ibid., 167. ↩︎

- Ibid., 166-67. ↩︎

- Ibid., 232. ↩︎

- Ibid., 145. ↩︎

- Ibid., 282. ↩︎

- Ibid., 251. ↩︎

- Ibid., 155. ↩︎

- Ibid., 158. ↩︎

- Ibid., 148-50, 154-55, 160-62. ↩︎

- Ibid., 175, 177, 182. ↩︎

- Ibid., 227-28, 234. ↩︎

- Ibid., 221. ↩︎

- Ibid., 236-37. ↩︎

- Ibid., 254. ↩︎

- Ibid., 280. ↩︎

- Ibid., 274. ↩︎

- Ibid., 279. ↩︎

- Ibid., 237. ↩︎

- Ibid., 238. ↩︎

- Ibid., 278. ↩︎

- Ibid., 275-76. ↩︎

- Ibid., 275-76. ↩︎

- Ibid., 273-74. ↩︎

- Ibid., 238. ↩︎

- Ibid., 238. ↩︎

- Ibid., 279. ↩︎

- Ibid., 279. ↩︎

- Ibid., 146. ↩︎

- Ibid., 282. ↩︎

- Francis Fukuyama, “Second Thoughts,” The National Interest, No. 56 (Summer 1999), 26. ↩︎

- Ibid., 31. ↩︎

- Ibid., 28. ↩︎

- Ibid., 28. ↩︎

- Ibid., 29. ↩︎

- Ibid., 30-31. ↩︎

- Ibid., 31. ↩︎

- Ibid., 32. ↩︎

- Ibid., 33. ↩︎