We propose to publish a journal of controversy, Modern Age. For the time being, our numbers will appear quarterly; later, if your interest appears to justify more frequent publications, we may make the review monthly. This present issue is our prospectus.

More people are literate in America than in any other country; we have several times as many college graduates as we had at the beginning of this century; yet probably there is less serious reading, per head of population, than in any other great nation. Every age has its own means for informing, amusing, and governing, so that we would be naive to expect the printed word and the journal of opinion to exert today precisely the same influence that they enjoyed during the nineteenth century.

But for all that, modern society cannot endure—and its survival is immediately in question—without discussion among thinking men. It will not do to leave the making of considered judgments, moral and social and imaginative, to radio commentators and newspaper editors, even though some men of intellectual power are to be found among them. Henry Adams remarked that the North American Review, under his editorship, exercised merely a trifling direct influence; but its indirect influence, because it was read by editorial writers and men of position throughout the United States, was profound. The best medium for expressing considered judgments still is the serious journal. And by serious journal we do not mean a dull and pompous review, but rather a magazine which endeavors to reach the minds of men who think of something more than the appetites of the hour.

This is not a time in which serious reviews prosper; and of such journals as are left to us in America, the majority are professedly liberal or radical. There is room in America for many liberal and radical journals in opinion; we hope there is also room for some conservative journals. Modern Age intends to pursue a conservative policy for the sake of a liberal understanding.

By “conservative,” we mean a journal dedicated to conserving the best elements in our civilization; and those best elements are in peril nowadays. We confess to a prejudice against doctrinaire radical alteration, and to a preference for the wisdom of our ancestors. Beyond this, we have no party line. Our purpose is to stimulate discussion of the great moral and social and political and economic and literary questions of the hour, and to search for means by which the legacy of our civilization may be kept safe.

We are not ideologists: we do not believe we have all the remedies for all the ills to which flesh is heir. With Burke, we take our stand against abstract doctrine and theoretic dogma. But, still with Burke, we are in favor of principle.

In the realm of foreign affairs especially, we believe, there is an urgent necessity for a return to principle. A considerable part of each issue of our journal will be devoted to the discussion of international questions and of American policy abroad. Foreign contributors will be welcome in our pages, and we shall endeavor to offer some intelligent account of life and thought outside America. The articles by Mr. Felix Morley, Mr. Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Mr. Béla Menczer, and Mr. J. M. Reid, in this present issue, will suggest the sort of discussion we hope to encourage. We feel that Mr. Morley’s essay, in particular, may stir up a healthy controversy over the American role in this century. Our section on the work of Ortega y Gasset, including two essays of his never before published in English, is intended to bring to Americans a reminder of the importance of recent Spanish thought; and we intend to deal similarly with the work of other European philosophers and men of letters.

And we shall have space for some examination of the mind and conscience of America. Perhaps we may succeed in attracting the interest of readers abroad to American points of view inadequately presented at present. We intend particularly to emphasize humane learning in the United States: religious and ethical matters, historical problems, and the foundations of politics. Published in Chicago, our journal may also serve to represent opinion in the heart of America, and to link the Middle West and South and West with the Eastern United States and with the world overseas.

Our object is not to pick quarrels, but to bring about a meeting of men’s minds.

We are endeavoring to publish a journal which will make it possible for contributors to write and think as well as they possibly can. We shall not try to be popular, and we shall try not to be didactic. We shall not be afraid of the long essay, or the long review-article, or of wit. We hope to publish a few distinguished short stories, and some good verse. We shall encourage the debate and the symposium. Sometimes we may undertake a review of reviews, surveying American journalistic opinion on questions of the hour. We shall be leisurely, and we shall not always be sober-sided. We shall try not to depend solely upon “current awareness” to attract readers; we shall seek, rather, to encourage and express considered judgments more important than this week’s or this month’s headlines. We shall not pretend to be able to predict next fall’s election or next year’s revolution. We do not aim to force our editorial opinions upon our readers. Our object is not to pick quarrels, but to bring about a meeting of men’s minds. Old Alfred Yule, in The New Grub Street, upon the prospect of founding a new critical review, growls, “How I shall scarify!” We, however, have no intention of scarifying; we think the American mind and the American heart, in this hour, require something more generous.

“The quality of civilization,” Miss Freya Stark writes, “depends on the calling of things by their proper names as far as we can know them.” We are going to try to call things by their right names: the essay by Mr. Wilhelmsen in this issue is a model in that endeavor. Among the articles we have scheduled for early publication are Mr. W. T. Couch’s “The Word and the Rope”; Mr. Willmoore Kendall’s “The Lay-man-Expert Dilemma”; some autobiographical pieces, commencing with Dr. Wilhelm Röpke’s autobiography of a political economist; “Differences between American and European Conservatism,” by Mr. Ludwig Freund; a long critical essay by Mr. Eliseo Vivas; “Some Reflections on the Problem of Universal Style,” by Mr. Rudolf Allers; “Republicans as Conservatives,” by Mr. Helmut Schoeck; “Toward a Christian Approach in Judging Economic Systems,” by Mr. David McCord Wright; “Matthew Arnold, the Dandy Isaiah,” by the Reverend B. A. Smith; an article on rural life by Father Leo R. Ward. And there are others as good in our bank. We shall have a symposium on American education.

This magazine needs contributors, and subscribers, and good counsel. We invite readers to send us their criticisms of this number, and we propose to publish a number of letters in each issue. We are fortunate in our board of editorial advisors, scholars who serve without payment. They are drawn from various occupations, hold various religious and ethical persuasions, and differ in their private opinions and political associations; but they share the conviction that there are elements in our American society worth conserving. Granted a kindly providence, and the support of thinking men and women, we hope to revive the best in the old journalism and to mold it to the temper of our time. With Burke, we attest the rising generation; and we think that our voices may be heard not merely by the generation that is passing, but also by the young men and women who are seeking some certitudes in this age oppressed by Dinos.

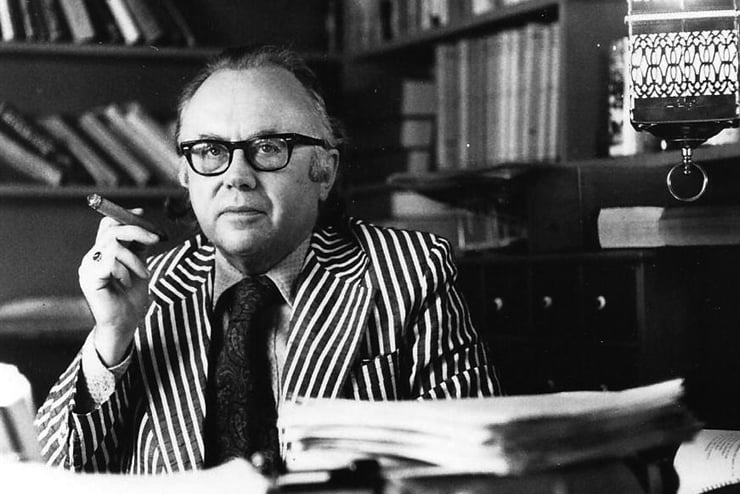

Russell Kirk was one of the principal founders of the modern conservative movement and one of the twentieth century’s foremost men of letters. He was the founding editor of Modern Age.