Surrealism was inaugurated a century ago by André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto. To celebrate the occasion, the Centre Pompidou in Paris is holding a major exhibition, which contains aesthetic creations and experiments—designs, paintings, films, photographs, and documents. For critics skeptical of the movement’s influence, such a show could be easy to write off as obscure, eccentric, and transitory flim-flam. So overtly commercial was some of the Surrealist star Salvador Dalí’s work that he was re-christened “Avida Dollars,” after all. But this would be a mistake: the effects of the Surrealist movement remain with us everywhere, in advertising, film, artworks, popular music, literature, and a generally ironic cultural ambiance that is suffused with a contradictory but vehement relativism. To understand the dark absurdism of our era, we must trace it to one of its major sources in the twisted heart of Surrealism.

The intentions of the Surrealist movement were subversive from the outset. There is a notorious passage in Breton’s publication The Surrealist Revolution in which he writes that “the simplest surrealist act consists of going out into the street, revolver in fist, and firing into the crowd as often as possible.” The charismatic Breton was a major cultural figure on the French and international scene for forty years. In 1991, a more recent French cultural icon, Bernard-Henri Lévy, published an amazingly embarrassing book, translated a few years later into English as Adventures on the Freedom Road: The French Intellectuals in the 20th Century. In it he argues that the violent publicity stunts and miscellaneous works of the Surrealists show them to have been “the first to initiate [a kind of terror] as a way of writing” and that they “gave literary authority to a particular verbal style of brutalizing and destroying their enemies.” Simultaneously a Surrealist and a Communist, the poet Louis Aragon (married to Elsa Triolet, a major Communist presence in Paris for thirty years) recommended of all the eminent “bourgeois” writers that “we judge them in the pure light of terror.”

The literary-philosophical inspirations of Breton and his allies and disciples were the criminal Marquis de Sade (whom they helped to exalt to cultural significance); les poètes maudits (the group of nineteenth-century French poets called “the accursed ones”); Nietzsche; and a left-wing, emancipatory reading of Freud as interpreter of dreams and liberator of the unconscious and the id. As the French critic Paulin Césari writes in an illuminating review in Le Figaro, Surrealism was a total war against all forms of order—social, cultural, moral, mental, and aesthetic. And the Surrealists refused to take seriously any idea that authority might be warranted and might differ from mere power. In this they predicted and predated by decades their compatriots and fellow Nietzscheans, Deconstructionists such as Michel Foucault—and innumerable contemporaries of ours.

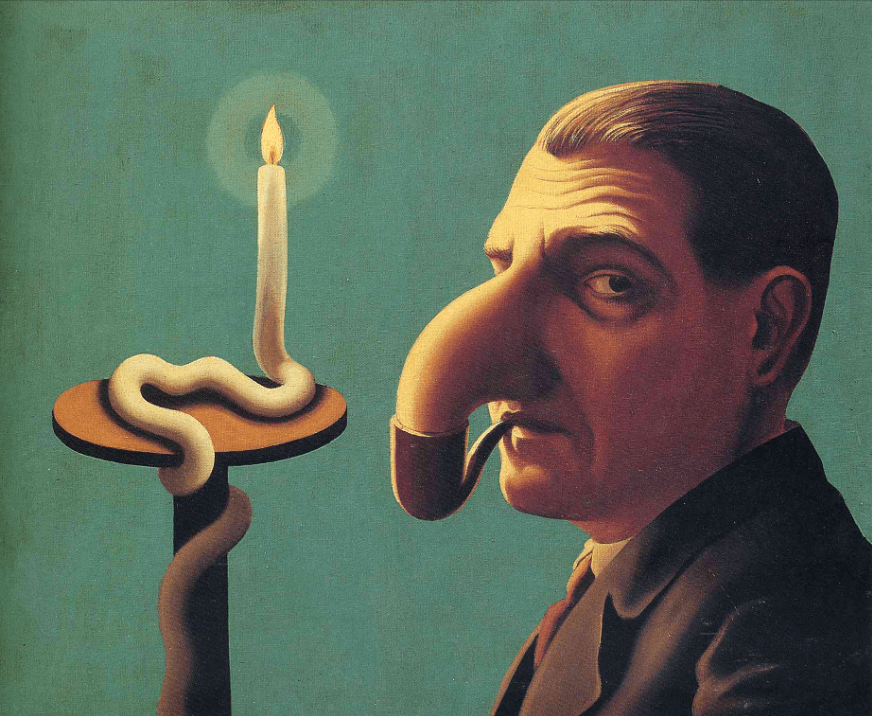

One of the mildest Surrealists in behavior (despite a spell as a forger and money counterfeiter), and one of the most effective in painting, was the Belgian René Magritte, to whom the Centre Pompidou devoted a major retrospective in 1979 that was welcomed with enthusiastic appreciation and praise by the eminent Anglophone critic Robert Hughes—“Enter the Stolid Enchanter.”

But I had a rather different and, if I may say so, a rather more intimate encounter with the Surrealist Magritte’s work a decade earlier in New York. In the late 1960s as a Columbia student I worked part time for about three years as an assistant to the director of the Byron Gallery on Madison Avenue. I helped arrange a small but important Magritte retrospective that was held in the gallery in November and December of 1968. Many months in advance I wrote letters soliciting loans of the paintings, helped get the catalogue printed (I still have a copy), assisted in hanging the show, and watched over and lived with the fifty paintings and drawings intimately for a month. Along with other events in the annus horribilis 1968, it was an experience of irony, disappointment, distress, and derangement.

Derangement was surely one of the great aims of the Surrealists, drawing on and exalting irrationalists such as Sade, les maudits, and Nietzsche. Magritte’s apparently whimsical disordering of expectations and his celebration of inconsequential miscellaneity seemed to Hughes the stuff of greatness. But to me Roger Shattuck’s later characterization of much of Surrealism as ironic trickery (“blague”) and ludicrous mystification ultimately makes more sense of him and much else in the Surrealist and post-Surrealist world.

For the Surrealists were truly nihilistic revolutionaries, although their fervent, ironic marriages to Communism were usually unwelcome to those grimly moralistic Communist puritans. The latter’s narrative, didactic, and propagandistic “Socialist Realism,” after all, was at an infinite remove from the Surrealists’ aggressive anarchism. Promethean Marxist “humanism” could see Surrealism only as one of the last, grotesque, decadent death rattles of the doomed bourgeois order.

In two distinguished scholarly essays in the 1970s, the Italian philosopher Augusto Del Noce argued for the depth and power of the Surrealist revolution in the West in its time and especially after World War II. He saw it as the key cultural battering ram of “psycho-erotic-Freudian-Marxist de-Christianization.” Del Noce conceived the legacy of Sade, Nietzsche, and the left-wing Freudian anarchist Wilhelm Reich (who died in Lewisburg Penitentiary in 1957) as promoting comprehensive “de-sublimation,” mindless exhibitionism, preening narcissism mixed with haughty moralism, and the resulting degradation of civilization. Distinguished American thinkers such as Jacques Barzun, Shattuck, Philip Rieff, and Daniel Bell have made related arguments. Himself the son of a French painter, the Franco-American historian Barzun called Picasso and the Surrealist Marcel Duchamp “that matchless pair of destroyers.” He also rightly said of our era that “the antinomian passion is the deepest drive of the age.”

Deconstruction was well underway from Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto onwards. In addition to artists, intellectuals and scholars of the humanities and social sciences have proved persistently vulnerable to the bacillus of “the transvaluation of all values” undertaken with spectacular iniquity by Sade and in brilliantly meretricious, aphoristic paradoxes by Nietzsche on his way to terminal madness. Paul Valéry helpfully assured us that “there is no such thing as the true meaning of a text.”

The real public victors of the culture wars of the last 125 years have not been the Fascists or the Marxists (despite their undeniable hecatombs of corpses) but the antinomian anarchists who have dismantled, and continue to dismantle, Aristotelian and Christian common sense in the West. The endless, multifaceted derangement goes constantly on, undermining traditional epistemology and ethics—any and all normative, “logocentric” conceptions of truth and ethics. C. S. Lewis called it “the abolition of man,” and Alasdair MacIntyre calls it living “after virtue.”

Regarding aesthetics, traditional ideas of and appetites for beauty and harmony are hated and mocked, taken to be utterly subjective, exhausted, superstitious, and bankrupt. The American painter Barnett Newman insouciantly wrote in 1948 that “The impulse of modern art [is] this desire to destroy beauty . . . by completely denying that art has any concern with the problem of beauty.” The philosopher Arthur C. Danto, longtime art critic of the Nation, says that by bringing art history to an end with his Brillo boxes, Andy Warhol is “the nearest thing to a philosophical genius the history of art has produced.” Brunelleschi, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Dürer, Vasari, Bernini, Goya, and John Ruskin don’t make the grade.

Of course there have been modern dissenters from “the age of the avant-garde,” not only among scholars and critics (such as Barzun, Shattuck, Kenneth Clark, and Hilton Kramer) but among artists, notably the distinguished Italian painter Pietro Annigoni. Some started out with the Surrealists and turned against them. According to Emily Braun, a specialist on the Italian painter Giorgio De Chirico, “Whereas the early work despairs over the irrevocable break with tradition, the later work flaunts, in parodic form, what culture has become. . . . De Chirico’s images can be read as a continuing commentary on the demise of high culture and traditional erudition.”

As true extremists, while styling themselves phenomenological pioneers the Surrealists seemed to oscillate between regarding consciousness itself as either ecstasy or nightmare. The Surrealists couldn’t bear the traditional constraints of the “examen de conscience,” which elicit its transcendental objects or measures: the good, the true, the beautiful, God. Evading these “outmoded” measures, their own consciousness was utterly anomalous, and for some of them, unbearable. Their experiments, effects, and personal fates seem to vindicate the profound insight of Emily Dickinson: “I do not know the man so bold / He dare in lonely Place / That awful stranger consciousness / Deliberately face.”

Their widespread legacy is wreckage, physical—a urinal, a litany of attention-grabbing stunts, pointless, parodistic contraptions, ironic canvases—and metaphysical: a ubiquitous anomie, irony, resentment, a pervasive relativism, and an irrational hostility to normative realities and to the beauty of the world itself.