African Founders: How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals

By David Hackett Fischer

(Simon & Schuster, 2022)

“The stories of American history,” David Hackett Fischer wrote in 1997, are better than they can ever be told.” The occasion was his acceptance of the Richard Weaver Award for Scholarly Letters, given by the Ingersoll Foundation and presented and printed in Chronicles magazine. Therein lies a tale of its own. Fischer was being honored for a lifetime of thinking about how to tell those untellable American stories, especially in his books Albion’s Seed and Paul Revere’s Ride. The speech caught me puzzling over how to tell the stories of the American colonies at Hillsdale College, and I had just decided to try it with a close reading of his books. But how to do it?

Part of the answer came in my next class. One of my students (who has since gone on to a very productive career in journalism) interrupted me to ask where this book (Albion’s Seed) came from and how I decided to use it. Before I could answer, her classmates started applauding—the book and me for choosing it!

After a short discussion, we decided to conspire to get Professor Fischer to campus. Our president was easy to convince, and eventually David Hackett Fischer spent several days with us, talking about the books and telling stories, the theme of which was that American freedom and liberty grew out of diverse local cultures that were mostly products of “Albion’s seed,” folkways that came from the British Isles. Then he gave a public talk titled “The Ebony Tree: Origins of African-American Culture.”

It was a remarkable story. He showed a discerning faculty and student body that just as we are all a little bit English, especially in our rule of law and political institutions, we are also, especially in our culture, a little bit African. We cannot fully understand how our culture of freedom and liberty develops and changes over time without seeking its origins in Africa as well as in Great Britain and Europe. The Ebony Tree talk eventually became African Founders, a new “companion volume” to Albion’s Seed.

But not right away. Despite the fact that most of the research was done, African Founders had to await new data; had to respond to new ways of thinking about the survival and growth of African culture in a slave system; and, perhaps most challenging of all, had to face the racial culture wars of what was variously called “multiculturalism,” “political correctness,” and “wokeness,” and had to be confronted by the pseudo-scholarship of the 1619 Project and “critical race theory.”

What makes African Founders an exciting and lasting way of telling many American stories is that Fischer made the courageous decision to ignore almost the entire woke controversy. As he said in 1997 about the controversy created by Albion’s Seed, “I wanted to know how and why an open society worked in America. My critics demanded to know why it was not more open.”

His generosity of spirit carries over into African Founders. “Racism in its infinite variations will always exist in America and elsewhere”—he is clear about that—“[b]ut to condemn the United States as a racist society is fundamentally false.” His inquiry was “to study African Americans, slave and free, as agents of change in the early history of the United States,” and this required a way of telling the stories without regard to the ideological battles that have dominated so much of academic scholarship and politics in the last several decades.

Fischer recognized, however, a generational element in some of these difficulties about who owns the past. Andrew Nelson Lytle often insisted that the “real slaves” are the ones who allow others to control their past, which is why so many oral cultures have given such a high rank to those who keep the past for the community. Fischer admits that as someone for whom “World War II was the defining public event on my youth,” he was predisposed to seek what was common to Americans about their past.

I understand this, being of the same generation. When we discussed this two decades ago, he remarked on an essay I had written about the war’s impact, in many essential ways cutting us off from the constitutional republic, making it harder to preserve what was best—and his reply was to say that World War II had “unleashed the full potential of American democracy.”

On reflection, we decided that both of us may be right. We were united, however, in rejecting ideology as a helpful way of looking either forward or backward, and of telling true stories.

Like Albion’s Seed, African Founders is a massive work of scholarship, but written in the plain language of an “inquiry” conducted mostly through empirical methods, centered on the regional cultures reflected in the census of 1790. That first census marked the high point of African Americans as a percentage of the American population, the result of the forced migration of about 458,000 Africans brought to British colonies in North America from West African ports. Although this represented a small percentage of the total slave trade, Fischer insists that the direct transmission of African cultures to the American colonies is crucial to what ultimately became the “mix of many mixtures” that made up a workable open society.

Fischer takes a regional approach, which is really the only way one can study early American history. Africans were brought to six “hearth regions” (New England, Hudson Valley, Delaware Valley, Chesapeake, Coastal South, Gulf Coast) and three “frontier regions” (Western, Maritime, Southern). Unlike the voluntary migrations he described in Albion’s Seed, where fully developed cultures (usually with clear goals for life in the new world) settled together, similar concentrations of African cultures were quite rare. Rather, the African Americans (the term favored from a very early time by their spokesmen) cobbled together new things and old in “creative” and complex cultural mixtures. Fischer’s subtitle, “How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals,” describes the many ways Africans enriched the cultures they were forced to endure.

Much of the book therefore focuses on the nature and conditions of slavery in the nine regions. Although there is not much new in these sections of the book, Fischer does bring data and scholarship up to date, refuses to engage in the older historiographical controversies, and states clearly that slavery was everywhere brutal and everywhere evil. Furthermore, “approximately all slaves resisted slavery in one way or another.”

He is for the underdog “approximately” 100 percent of the time, including in the often delightful descriptions of his travels in Africa and the West Indies and the generous credit he gives to data collectors and even some rather questionable oral histories. Like Herodotus (and, one could say, Francis Parkman and Samuel Eliot Morison), for Fischer an important part of telling stories is “Going There.” He has done that, and therefore his telling of where slavery took place is as empirical as possible and despite his clear preferences is never ideological.

True to his conviction that American stories should emphasize what is common in our regional cultures, Fischer’s African Founders’ contributions “grew from African cultural roots, and developed through interactions with European cultures and American environments.” But despite the often careful research done by American slave owners and their rather surprising knowledge about the tribal cultures from which they tried to take men and women, it was rare for large numbers from particular African cultures to locate in any one of the nine regions he discusses. Full-blown African tribal cultures rarely appeared in the British colonies; therefore categories such as comity, family ways, speech ways, building ways, etc., that dominated the pages of Albion’s Seed do not appear in African Founders. The common stories are gathered from “complexities” (Fischer uses this word and “creative” far too much) that are often hard to assign to clear cultural folkways.

One example, although there are many: marriage and family life were much more complex than either the Moynihan Report of the 1960s or the slave codes of southern regions would have us believe. Despite the ability of slave owners in the Chesapeake and coastal areas to break up families at will, and despite the many laws limiting legal protections of marriage contracts almost everywhere, the African American commitment to nuclear families and two-parent living remained remarkably consistent. At the same time, African marital customs, including polygamy, did not disappear, and marriage ceremonies outside of New England and the Hudson Valley were sometimes amusing in their simplicity. Overall, slave and free and mixed African marriages created families and over time took on most of the characteristics of the Christian churches that most African Americans embraced. How else to explain, as Walter Williams did so eloquently in his speeches, that as late as 1939 what we used to call “illegitimacy” was lower among African Americans than among whites?

Perhaps the most difficult part of David Hackett Fischer’s inquiry is to convince the reader that the cultural dynamics which produced a fuller development of “American ideals” were as African as he claims. It would be easy to think that most African American “contributions” to an open society and a “larger spirit of equality” were chiefly a matter of the forced immigrants accepting and adapting to western European folkways. We all know about what Fischer calls African “gifts of language and speech,” “gifts of music,” and the wondrous thing called “soul.” But what about the places and jobs that constitute American life? This is where most of us live, on the farms and ranches and waterways, in the neighborhoods and factories, the schools and churches, where our notions of liberty and morality grow and fail and are reflected.

Taken as a whole, this is where African Founders is most effective. And, dare we say, most conservative. Most of the personal stories Fischer tells are of African Americans few of us have ever heard of. They are snapshots rather than biographies, a method of inquiry for which many readers criticized the author in Albion’s Seed. But how else to bring it to life?

Black Alice, Yarrow Mamout, Solomon Northup, Daniel Coker, George McJunkin, Bob Lemmons, Addison Jones, Marion, John Horse, and a hundred others whose names we haven’t heard before show how African Americans brought skills as warriors, farmers, cowboys, boat builders, linguists, carpenters, and a hundred other crafts to the founding of a country that was paradoxical but strong.

Part of that strength, David Hackett Fischer insists, was and is due to the ability of African Americans to face the evil, recognize the good, and help to build not what was progressive or utopian but what is hopeful of liberty and freedom, standing on what came before.

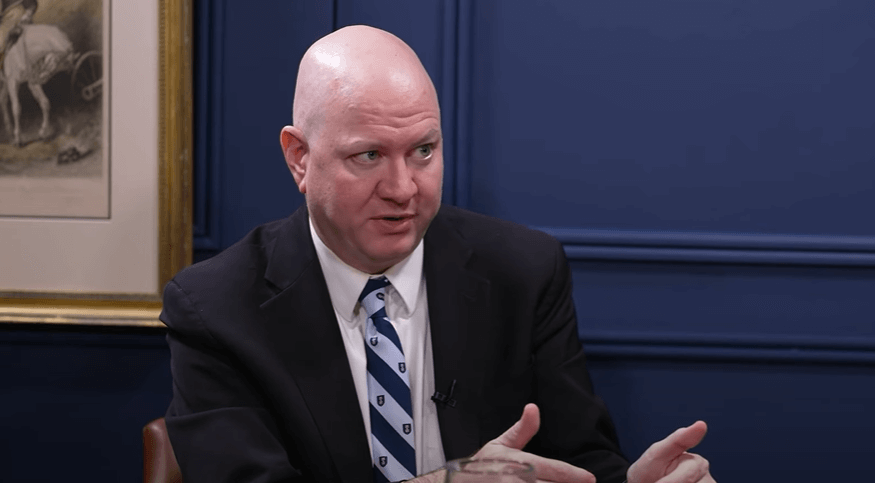

John Willson is professor of history emeritus at Hillsdale College.