What Matthew Arnold called “an epoch of concentration” impends over the English-speaking nations. The revolutionary impulses and the social enthusiasms that dominated our century since their great explosion in Russia are now confronted by a countervailing physical and intellectual force. Fanatic ideology has been, in essence, rebellion against the old moral order of our civilization. To resist ideology, certain principles and usages of order have been waked, quite as they stirred against French innovating fury after 1790. We have entered upon a time of reconstruction and revaluation; we discern a resurrected conservatism in politics and philosophy and letters.

Britain during Arnold’s “epoch of concentration” became, despite its disillusion, a society of high intellectual achievement, the revolutionary energy latent in it diverted to reconstructive ends. That the epoch of concentration displayed moral qualities so powerful, that it did not sink into a mere leaden reaction, Arnold attributed to the influence of Edmund Burke. Indeed Burke succeeded in death, beyond his own last expectations, at his labor of upholding the order of civilization. “The communication of the dead is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living.” Let me add to the name of Edmund Burke the great names of Samuel Johnson and Adam Smith: and permit me to suggest to you, very succinctly, how these three men of the latter half of the eighteenth century explained and defended that social and moral order which endures to our own present troubled decade.

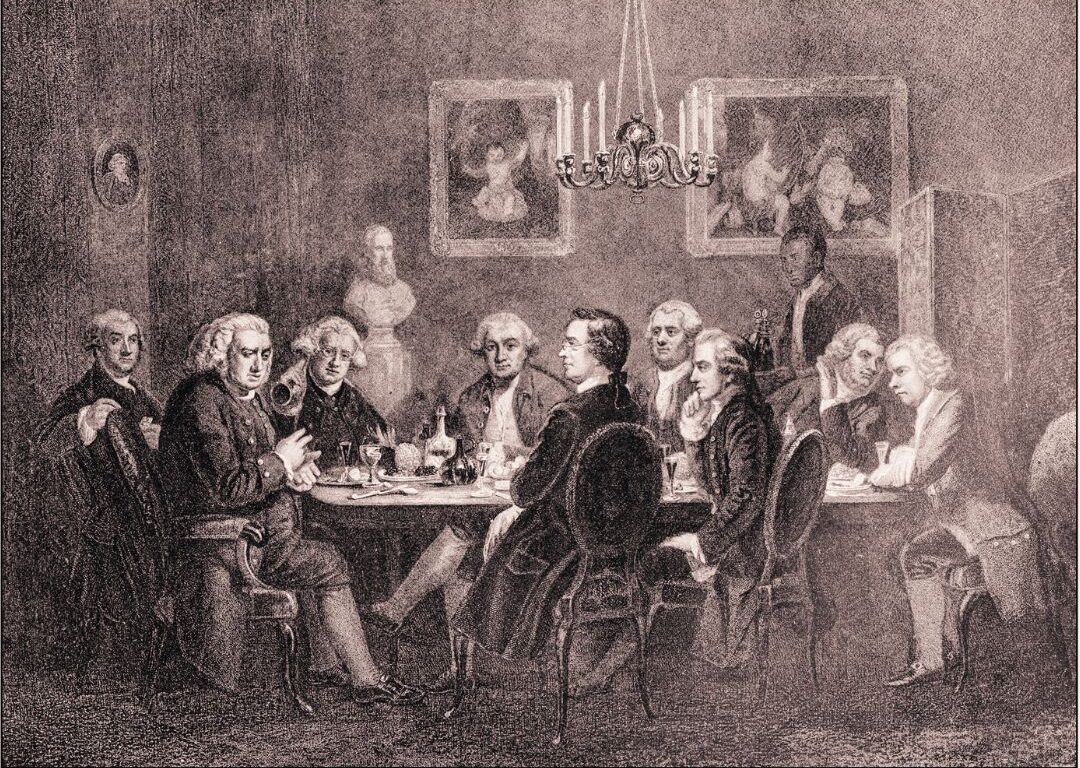

Although the three great men knew one another, they were not intimates; Smith and Johnson, indeed, were adversaries. Burke was a practical leader of party, Johnson a poet and a critic, Smith a professor (nominally) of moral philosophy. (Actually, he at once converted his Glasgow appointment into a chair of finance and political economy.) Johnson was a Tory; Burke and Smith were Whigs. Doubtless their ghosts would be astonished to find their names joined amicably near the end of the twentieth century. Yet it may be said of them what T. S. Eliot wrote of the partisans of the English Civil Wars: they “Accept the constitution of silence / And are folded in a single party.” What party, nowadays? Why, we may call it the party of order.

All three men were moralists: all were realists and shrewd observers; all gave primacy to order in the commonwealth. I propose to touch briefly upon some of their several convictions, to compare the three, and to suggest their relationships. We turn first to Burke, about whom I have written much—probably too much.

In 1790, when Burke published his Reflexions on the Revolution in France, he had been a politician for thirty years. Yet his ambition it had been, in his youth, to succeed as a man of letters, eschewing “crooked politicks.” Like Johnson, Burke was a man of letters who derived his politics from his ethics and his knowledge of history (as well as from his intensive practical experience, in Burke’s case); but unlike Johnson, he made politics his career. It took the catastrophe of the French Revolution to divert the Whig politician from practical statecraft to consideration of the first principles of the civil social order.

When only seventeen years old, Burke had glimpsed the abyss into which the Enlightenment would tumble. “Believe me,” he wrote then to a friend, “we are just on the verge of Darkness and one push drives us in—we shall all live, if we live long, to see the prophecy of the Dunciad fulfilled and the age of ignorance come around once more. . . . Is there no one to relieve the world from the curse of obscurity? No, not one. . . .” And he quoted Vergil: “The Saturnian reign returns and the great order of the centuries is born anew.”

By 1790, Saturn was in arms. Anacharsis Cloots wrote to Burke in May of that year that Europe should have no more Gothic architecture: Notre Dame would be pulled down, and a harmonious Temple of Reason would be erected on the cathedral’s site, to be admired by all connoisseurs of the arts. But Burke resolved that the sublimity of Christian religion, and the Gothic edifice of European civilization, should not be submitted to the wrecker’s bar. Against an armed doctrine, a revolution of moral ideas carried on by violence, Burke contended with all his power. His determination it was to refurbish “the wardrobe of a moral imagination.” Passions once unchained; abstract benevolence and enlightened poses would not suffice to keep men from anarchy, Burke knew. The obscene and the terrible, the sensual and the dark, rise out of the depths when moral authority is derided. For man comes out of mystery, and is plunged back into grisly obscurity when he presumes to fancy himself the rational master of everything on earth. So ran Burke’s burning rhetoric in his later years. There are flames of glory, and flames of damnation. We are born into a moral order, Burke told England; and if we defy that order, our end is darkness.

“Burke gives the state a soul,” Hans Barth writes. “He makes it personal, he fills it with the values and contents of the individual soul. He wants to make it worthy of devotion and of the possible sacrifice of one’s life.” Burke perceived that the just state exists in a tension between the claims of authority and the claims of freedom. And love of country, like love of kindred or friends, Burke knew, cannot be the fruit of mere rational calculation. Nothing, he said, is more evil than the heart of a thoroughbred metaphysician—that is, of the “intellectual” who enthrones his ego and his private stock of reason upon the ruins of love, duty, and reverence.

In the Jacobins, Burke perceived the fanatics of the armed doctrine, determined to sweep away Christian love and the old rule of law—the revolt of the arrogant enterprising talents of a nation against property and the traditions of civility. It remained for the men of the Napoleonic era to coin the word “ideologue” to describe this passion for innovation, this violent eagerness to abolish the old morality and the old social order, that the New Jerusalem might be created on principles of pure reason.

To resist the Jacobins, Burke undertook what Louis Bredvold justly called “the reconstruction of social philosophy.” Like Plato in another time of disorder, Burke endeavored to adapt the ancient structure of his civilization to the challenges of the age. Knowing that mankind really is governed not by the speculations of sophists, but by a “stupendous wisdom molding together the great mysterious incorporation of the human race,” Burke sought to revive the understanding of “the contract of eternal society.”

One of the more lively disputes over Burke’s meaning has arisen from the question of whether Burke was primarily a man of enduring principles, or a champion of expediency and empiricism; whether he stood in the “great tradition” of classical political thought, or was a Romantic irrationalist. This controversy seems to have been stirred up chiefly by a passage in Leo Strauss’ Natural Right and History. “Burke comes close to suggesting that to oppose a thoroughly evil current in human affairs is perverse if that current is sufficiently powerful,” Professor Strauss wrote; “he is oblivious of the nobility of last-ditch resistance.” Although the late Leo Strauss was an admirer of Burke, this observation of his has been carried by others to a general denunciation of Burke as a guide in a time of revolution.

The concluding paragraph of Burke’s Thoughts on French Affairs (1791) is the source from which Strauss’ criticism issues. “If a great change is to be made in human affairs,” Burke wrote, “the minds of men will be fitted to it, the general opinions and feelings will draw that way. Every fear, every hope, will forward it; and then they, who persist in opposing this mighty current in human affairs, will appear rather to resist the decrees of Providence itself, than the mere designs of men. They will not be resolute and firm, but perverse and obstinate. ”

Burke’s hostile critics interpret this passage to mean that in Burke’s view principles change with times, and morals with climes; and that (anticipating Hegel) we ought not to oppose futilely the March of History. But this interpretation of Burke ignores Burke’s actual course. Anyone interested in the matter ought to re-read Thoughts on French Affairs. Therein Burke does not hint that perhaps the champions of religion and of things established ought to let themselves be swept away by the current of the French Revolution. On the contrary, he says that effectual opposition to the Revolution must be the work of many people, acting together intelligently: he professes his inability, as an old politician retired from Parliament and separated from his party, to do more than to declare the evil. The “mighty current” for which he hopes is an awakening of the men with “power, wisdom, and information” to the peril of the Revolution: he is asking for a surge of public opinion in support of things not born yesterday. Providence ordinarily operates through the opinions and habits and decisions of human beings, Burke had said years before; and if mankind neglects the laws for human conduct, then a vengeful providence may begin to operate. Of all men in his time, Burke was the most vehemently opposed to any compromise with Jacobinism. He would have chosen the guillotine rather than submission—or, as he put it, death with the sword in hand. He broke with friends and party, sacrificing reputation and risking bankruptcy, rather than countenance the least concession to the “peace” faction in England.

Neither an irrational devotee of the archaic, nor an apostle of the utilitarian society that was emerging near the end of his life, Edmund Burke looms larger every year, in our time, as a reluctant philosopher who apprehended moral and social order. Practical politics, he taught, is the art of the possible. We cannot alter singlehandedly the climate of opinion, or the institutions of our day, by a haughty adherence to inflexible abstract doctrines. The prudent statesman, in any epoch, must deal with prevailing opinions and customs as he finds them—though he ought to act in the light of enduring principles (which Burke distinguished from “abstractions,” or theories not grounded in a true understanding of human nature and social institutions as they really are.)

Burke might have been many things—among those, a great economist. Adam Smith declared that Burke’s economical reasoning, as expressed in Burke’s Thoughts on Scarcity, was closer to his own than that of anyone else with whom he had not directly communicated. As editor of The Annual Register for many years, and architect of such elaborate pieces of legislation as the Economical Reform, Burke was intimately acquainted with the science of statistics in its eighteenth-century genesis. Yet Burke often expressed his dislike of “sophisters, economists, and calculators,” by whom the glory of Europe was extinguished. Elsewhere in the Reflexions, he argues that industry and commerce owe much to “ancient manners,” to the spirit of a gentleman and the spirit of religion, and would fall without the support of those ancient manners; yet he remarks with some contempt that “commerce, and trade, and manufacture” are “the gods of our economical politicians.” Despite the Whigs’ commercial connections, Burke remains strongly attached to the agricultural and rural interests. He rebukes obsession with economic concerns, perceiving that society is something vaster and nobler than a mere commercial contract.

Burke reviewed favorably The Wealth of Nations in The Annual Register, and occasionally met Adam Smith at the Club, in London. Smith was Burke’s host in Edinburgh, in 1784, and they met there again in 1785; Smith obtained Burke’s nomination to the Royal Society of Edinburgh. They were friendly, in short, but not close collaborators. Many parallels may be drawn between their respective remarks on political economy; but it should be noted that Smith, in his social assumptions, was more of an individualist than was Burke. I suspect that Burke may have been a trifle uneasy with Smith because of Smith’s intimate friendship with the great skeptic David Hume, against whose first principles Burke set his face. (For his part, Hume desired Burke’s friendship, and it was Hume who first introduced Smith to Burke’s writings, telling him to send a copy of his Theory of Moral Sentiments to “Burke, an Irish gentleman, who wrote lately a very pretty treatise on the Sublime.”)

With Samuel Johnson, Burke’s connection was dearer and more interesting. We take up the great man of Gough Square.

“The first Whig was the Devil.” A good many people know little more of Samuel Johnson’s politics than this witticism, which does suggest, indeed, Johnson’s emphasis on ordination and subordination. But Johnson was a political thinker of importance, though no abstract metaphysician in politics.

It will not do to look at Johnson through the spectacles of “the Whig interpretation of history” or on the basis of silly commentaries in popular literature textbooks which result from ignorance of Johnson’s doctrines and milieu. The political Johnson was a reasonable, moderate, and generous champion of order, quick to sustain just authority, but suspicious of unchecked power. If one analyzes his Tory pamphlet Taxation No Tyranny, one finds that Johnson merely was stating the long accepted and still valid definition of the word “sovereignty” as a term of politics—not advocating absolutism.

There runs through Johnson’s works a strong vein of disillusion and doubt of human powers, a sense of the vanity of human wishes. This is part and parcel of the Christian dogmata that governed Johnson’s life. Certainly it shaped his political convictions. Dr. Raymond English speaks of “the rather brutal skeptical streak in Johnson’s Toryism. It seems to me that Johnson is rather like Dean Inge in that he combines a profound mystical Christian faith with a fierce pessimism about practical politics. Possibly one should compare both these to St. Augustine, for whom the fall of man had rendered natural law a somewhat inadequate basis for political authority. In a slightly different way, Fitzjames Stephen plays upon a similar theme.”

Neither Burke nor Johnson would have been pleased to be styled a “political philosopher.” Perhaps Johnson, in his political aspect, is best described as “statist”—which word has a neutral character in Johnson’s Dictionary. What Ross Hoffman said of Burke is even more true of Johnson: “He took his first principles in politics from the Authorized Version and the Book of Common Prayer.” Granville Hicks once wrote of Robert Louis Stevenson, “The Tory has always insisted that, if men would cultivate the individual virtues, social problems would take care of themselves.” This is true in essence of Johnson’s view of human nature and society; yet Johnson did not ignore the part of institutions in a tolerable social order. Far from being an absolutist, he stood for the rule of law in a polity, the libido dominandi checked by custom and Christian doctrine.

“The Whigs will live and die in the heresy that the world is governed by little tracts and pamphlets,” Walter Scott wrote once—Scott, who stood directly in the line of Johnson. Into that heresy Samuel Johnson did not slip. His politics did not come from sixteenth- or seventeenth- or eighteenth-century tracts, but from experience of the world, from much reading of the politically wise over many centuries, and from what Eliot calls “the idea of a Christian society,” with its concepts of ordination and subordination, charity and justice, divine love, and mortal fallibility.

Whig magnates and demagogic “patriots,” Johnson was convinced, meant to break in upon the balance of orders and powers that was eighteenth-century England—an argument later advanced by Disraeli, in the preface to Sybil. For Johnson, the Devil was the first Whig because the Whigs stood for insubordination and innovation; Burke was a “bottomless Whig,” in Johnson’s epithet, because the Whigs clung to no well-defined principles of social order, but lived by expediency and extemporization. Such ejaculations about Whigs, nevertheless, often extracted by Boswell from Johnson in moments whimsical or splenetic, were not Johnson’s deeper reflections. At Boswell’s request, in 1781, Johnson set down in writing the distinctions between Whig and Tory:

A wise Tory and a wise Whig, I believe, will agree. Their principles are the same, though their modes of thinking are different. A high Tory makes government unintelligible; it is lost in the clouds. A violent Whig makes it impracticable; he is for allowing so much liberty to every man, that there is not enough power to govern any man. The prejudice of the Tory is for establishment; the prejudice of the Whig is for innovation. A Tory does not wish to give more real power to Government; but that Government should have more reverence. Then they differ as to the Church. The Tory is not for giving more legal power to the Clergy, but wishes they should have a considerable influence, founded on the opinion of mankind; the Whig is for limiting and watching them with a narrow jealousy.

As Leslie Stephen wrote, “The Whigs were invincibly suspicious of parsons.” Johnson was not so suspicious.

It may be perceived that the first principles of such a Tory as Johnson and such a Whig as Burke were very nearly identical. To both, the new politics of the dawning era, whether the notions of Rousseau or of Bentham, were abhorrent. Both Johnson and Burke recognized a transcendent moral order, subscribed to the wisdom of the species, were attached to custom and precedent, upheld the idea of the Christian magistrate, and adhered to the venerable concepts of Christian charity and community. The narrow contract-theory of Locke, the skepticism of Hume, the tendency toward individualism in the writings of Smith—these were inimical to both the Toryism of Johnson and the Whiggery of Burke.

When, at the end of his career, Burke refuted Goldsmith’s playful reproach by giving to mankind what once he had owed to party, the Old Whig’s principles were almost indistinguishable from those of his friend Johnson, who had died before the Deluge of 1789. “I can live very well with Burke,” Johnson had said; “I love his knowledge, his diffusion, and affluence of conversation.” Or, on another occasion, “Yes, Sir, if a man were to go by chance at the same time with Burke under a shed to shun a shower, he would say—‘we have had an extraordinary man here.’”

It was otherwise with Johnson and Smith. Walter Scott, in a letter to John Wilson Croker written in 1829, records someone’s account of a meeting between Johnson and Smith at Glasgow—or rather, the account of it said to have been extracted not long later from Adam Smith:

Smith, obviously much discomposed, came into a party who were playing at cards. The Doctor’s appearance suspended the amusement, for as all knew he was to meet Johnson that evening, every one was curious to hear what had passed. Adam Smith, whose temper seemed much ruffled, answered only at first, “He is a brute! he is a brute!’’ Upon closer examination it appeared that Dr. Johnson no sooner saw Smith than he brought forward a charge against him for something in his famous letter on the death of Hume. Smith said he had vindicated the truth of the statement. “And what did the Doctor say?” was the universal query: “Why, he said—he said—” said Smith, with the deepest impression of resentment, “he said—You lie!” “And what did you reply?” “I said, ‘You are a son of a bitch!’” On such terms did these two great moralists meet and part, and such was the classic dialogue betwixt them.

Birkbeck Hill doubts the veracity of this incident; however that may be, it represents well enough the degree of esteem in which the two moral philosophers held each other. We shall touch upon the reasons for this animosity as we sketch the Scots professor.

The unacknowledged debt to Adam Smith’s writings is even larger than the influence generally recognized. One finds in the volumes of John Adams, for instance, a very shrewd and seemingly original (so far as any psychology can be called original) analysis of the moral nature of man. At least I took it to be original, until recent years; then I discovered that many of Adams’s passages, and indeed the greater part of his convictions on this grand subject, are borrowed—almost plagiarized—from Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments, published in 1759. (Similarly, much of the account of the American Revolution in John Marshall’s Life of Washington is lifted from Burke’s Annual Register.) America’s borrowing from the Old World did not terminate in 1776.

But it was as a financier, rather than as a moralist, that Smith moved the men of his time. I possess and use the third edition of An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, published in 1786—the edition owned and so highly praised by Robert Burns. The great reason for the book’s practical success was its combination of genuine learning with a profusion of canny Scottish commonsensical observations—and the whole written lucidly and dispassionately. Charles James Fox said of the earlier editions, in an address to the House of Commons in 1783:

There was a maxim laid down in an excellent book on the Wealth of Nations, which had been ridiculed for its simplicity, but which was indisputable as to its truth. In this book it was stated, that the only way to become rich was to manage matters so as to make one’s expenses not exceed one’s income. This maxim applied equally to an individual and to a nation. The proper line of conduct, therefore, was by a well-directed economy to retrench every current expense, and to making as large a saving during the peace as possible. . . . He should not think that, as prospect of recovery was opened, the country was likely to be restored to its former greatness, unless ministers contrive some measure or other to pay off a part at least of the National Debt, and did something towards establishing an actual sinking fund, capable of being applied to a constant and sensible diminution of the public burdens.

The phrase “applied equally to an individual’’ on the lips of the profligate Fox may have provoked at least smiles from the opposite benches. For that matter, Smith himself was not much favored with the goods of fortune. (Fox’s praise did much increase the sales of The Wealth of Nations, so enlarging its author’s resources.) To Charles Butler, Fox later confessed that he never actually had read Smith: “There is something in all these subjects which passes my comprehension; something so wide, that I could never embrace them myself or find any one who did.” Of how many other public men who quote philosophers is Fox’s confession true!

Yet what the Arch-Whig could not apprehend, the Arch-Tory did. The younger William Pitt found in Smith the sagacity demanded for financing a quarter-century of war. In his Budget Speech of February 17, 1792, Pitt discussed as one of the causes of the increase of national wealth “the constant accumulation of capital, wherever it is not obstructed by some public calamity or by some mistaken and mischievous policy. Simple and obvious as this principle is, and felt and observed as it must have been in a greater or less degree even from the earliest periods, I doubt whether it has ever been fully developed and sufficiently explained but in an author of our own time, now unfortunately no more (I mean the author of the celebrated treatise on the Wealth of Nations) whose extensive knowledge of detail and depth of philosophical research will, I believe, furnish the best solution of every question connected with the history of commerce, and with the system of political economy.”

In America, during the same period, The Wealth of Nations runs through all of Alexander Hamilton’s principal financial reports. Also Hamilton’s opponents drew upon the Smith well of economic wisdom for some of their arguments. Ever since that age, on both sides of the Atlantic, those who sit in the seats of the mighty either have given lip service to Adam Smith or else have employed his great book without bothering to cite the source of their prescience.

Great influence sometimes proceeds from small and obscure origins. Smith’s observation of the decline of the small industry of nail-making in his native burgh of Kirkcaldy led him to reflect upon the division of labor; and his analysis of the division of labor grew into The Wealth of Nations. Very much the Scottish professor, Smith was so engrossed lifelong by the subject of the division of labor that on one occasion he was nearly extinguished by it. The London Times, in its obituary of Smith (who died in 1790), somewhat unkindly recorded one professorial episode of this character. When Charles Townshend, the politician, visited Glasgow, Dr. Smith took him to see a tannery:

They were standing on a plank which had been laid across the tanning pit; the Doctor, who was talking warmly on his favorite subject, the division of labour, forgetting the precarious ground on which he stood, plunged headlong into the nauseous pool. He was dragged out, stripped, and carried with blankets, and conveyed home on a sedan chair, where, having recovered of the shock of this unexpected cold bath, he complained bitterly that he must leave life with all his affairs in the greatest disorder; which was considered an affectation, as his transactions had been few and his fortune was nothing.

Actually, Smith survived this disaster; and his reputation has survived the crash of empires. Not so his Glasgow, or his Kirkcaldy. Until recently, Glasgow was one of the great stone-built cities of the world; but in recent decades public policies for which the most kindly word is “inane” have reduced nearly the whole of the old city to total dereliction or howling slum—by ignoring, along with much else, certain principles expounded in The Wealth of Nations. As for Kirkcaldy, where linoleum supplanted nails, an American documentary film about that burgh was produced a few years ago—or rather, a film about Smith’s life and work, in which there were scenes of modern Kirkcaldy, represented as a hive of industry of the sort made possible by the triumph of Smith’s economic ideas. Kirkcaldy I happen to know too well; and the bustling industry shown in the film is mostly a state socialist operation, run at a loss; and Kirkcaldy has one of the highest unemployment rates in Britain; and nearly all the curious old buildings associated with Smith and the Kirkcaldy of his time have been thoughtfully demolished, to be replaced by ugliness or by rubble-strewn vacant lots. A prophet is not without honor . . .

But I digress. Earlier I promised to point out why Johnson did not love Smith. One reason for this is that Smith did not love Johnson. In his early Rhetorical Lectures, Smith proclaimed, “Of all writers ancient and modern, he that keeps the greatest distance from common sense is Dr. Samuel Johnson.” On the other hand, Smith once told Boswell that “Johnson knew more than any man alive.” Boswell had studied under Smith at Glasgow; on one occasion he mentioned to Johnson that Smith preferred rhyme to blank verse. “Sir,” replied Johnson, “I was once in company with Smith, and we did not take to each other; but had I known that he loved Rhyme as much as you tell me he does, I should have hugged him.” The two did meet later occasionally at the Club, in London, and seemingly were civil enough in disputes. But Smith had reviewed Johnson’s Dictionary in hostile fashion; and for that Johnson did not forgive him.

These small matters aside, a gulf was widening even in the last quarter of the eighteenth century between men of intellect who professed Christian dogmata, and men of intellect who had their liberal doubts. Johnson and Burke were of the former party; Smith was Hume’s warmest admirer. As Manning said, all differences of opinion are theological at bottom. Smith was no atheist; yet his animadversions on the church, in the first edition of The Wealth of Nations, disquieted even his good friend Hugh Blair, the famous liberal preacher of the age, who wrote to Smith in April, 1776: “But in your system about the Church I cannot wholly agree with you. Independency was at no time a possible or practicable system. The little sects you speak of would, for many reasons, have combined together into greater bodies and done much mischief to society.” By such remarks, Smith had raised up formidable adversaries, Blair told him. Johnson was one such, no doubt; and Burke, though an energetic friend to religious toleration, was no admirer of the dissidence of dissent.

Finally, there were differences of temperament and social assumptions among these three. Burke was very much an Irishman, Johnson very much an Englishman—and Smith redoubtably a Scot. His mind was the mind of a Scottish Whig, however urbanely professorial Smith might be. William Butler Yeats, in his poem “The Seven Sages,” suggests that Burke, though a Whig nominally and occupationally, deep down detested the whole Whig cast of mind and character:

All hated Whiggery; but what is Whiggery?

A levelling, rancorous, rational sort of mind

That never looked out of the eye of a saint

Or out of drunkard’s eye.

Johnson feared Hell and venerated saints; Burke sometimes was facetious in his cups, and read “the fathers of the fourteenth century.” Smith appears to have been sober always, and not given to visions of the world beyond the world. It is a great way from Kirkcaldy to Dublin or to Litchfield.

Be that as it may, Burke and Johnson and Smith, in their several ways, described and defended those beliefs and institutions that maintain the beneficent tension of order and freedom. All were pillars of what Burke called “this world of reason, and order, and peace, and virtue, and fruitful penitence”; all knew how men and nations may make choices that cast them “into the antagonist world of madness, discord, vice, confusion, and unavailing sorrow.” Such frantic choices are being made two centuries after these three lived and breathed and had their being. So I do not find it at all surprising that some among us, in what we hope will be an era of concentration rather than of eccentricity, are reading afresh Burke and Johnson and Smith.

Russell Kirk was one of the principal founders of the modern conservative movement and one of the twentieth century’s foremost men of letters. He was the founding editor of Modern Age.