Why, as a Muslim, I Defend Liberty

By Mustafa Akyol

(Cato Institute, 2021)

The very essence of freedom is attacked, denigrated, and desecrated in our society today. To some, personal liberty doesn’t matter at all, while others feel they can arbitrarily determine who should or shouldn’t be free. In the midst of these underlying, and lately pandemic-induced problems of freedom lies an important question about religion and its relation to liberty.

For many it might seem odd to utter words “liberty” and “Islam” in the same sentence as complementary terms, but there is more to this relationship than cliches or biases suggest. In Why, as a Muslim, I Defend Liberty, the journalist Mustafa Akyol lays out the case for Islam’s inherent disposition toward liberty. The idea of liberty is not only a Western creation, claims Akyol, and he explores the rich tradition of Islam, showing the philosophical, theological, and cultural connections between liberty and religion.

Akyol rejects ideology (be it Islamist or Western Marxist) as well as ideological attacks on the Western tradition. He is an exceptional thinker, and while he makes specific arguments which may cause disagreements, his intellectual spirit is never divorced from the spirit of charity and faith. While Akyol rightfully does not apologize for his Muslim faith, he also does not seek to discard Western ideas and ideals.

One of the paramount issues within Islam is the idea of compulsion. Some Muslim countries are incredibly strict in how they demand that people live day to day. Akyol recounts an experience he had while traveling from the Saudi capital, Riyadh. While on an airplane, he witnessed a group of women who boarded the flight covered practically from head to toe in ultra-traditional clothing. Before the plane landed in Istanbul, they had all removed their veils and changed into more relaxed clothes, some of which bordered on inappropriate. The extreme contrast revealed (no pun intended) how much ordinary Muslims desire liberties that their states and societies too often deny.

Akyol addresses these concerns by exploring different spheres of life that depend on freedom. First and foremost, he goes into the source of Islam—Qur’an—and presents an interpretation of the famous second sura, which states, “There is no compulsion in religion.” Yet a problem arises in interpretation of this verse, just as in the political and cultural realities of different Muslim countries. As Akyol writes, “some Muslims indeed perceive Islam, in part, as a state: a totalitarian one that interferes deeply in individual lives, and also a jealous one that does not let them go.” In this view, if a Muslim yearns for liberty, he is deluded, and all his ideas about freedom are merely Western nonsense that needs to be fought against.

While it’s obvious that the idea of liberty has expanded the most in Western societies, there are seeds of it to be found in Islam. Akyol acknowledges John Locke’s great contribution in the West and argues that Islam has strayed from its riches as a tradition. First political power in the pre-modern world, and then ideology of the modern world, put the brake on the spiritual and intellectual development of Islam. There is now a crisis within different Islamic sects and societies, which must be addressed within those particular communities. According to Akyol, they have forgotten, or willingly ignored, that reason is inherent in the faith. Yet the important thing is that the “seeds of freedom” are there and “show that the values of modern-day liberalism also had Islamic roots, which require some excavation and cultivation today.”

Part of the problem lies in an interpretation of Sharia, Islam’s sacred law. “We can’t judge medieval Islamic jurisprudence by today’s standards, which would be a mistake,” Akyol writes. Yet laws change even in the most freedom-based societies, and Akyol calls for change in Muslim countries that “still see the standards of that medieval Islamic jurisprudence, which reflect the culture of those times, as the divinely mandated Sharia that is valid for all times and all people.”

Akyol also believes that we need to reflect openly on Islam’s legacy of “conquest” and “supremacy.” According to Akyol, however, “the Prophet didn’t actually establish an Islamic state. Instead, he established a civil state.” This was made up of different communities, not only Muslims but also adherents of other faiths. Akyol admits that “this 7th-century contract wasn’t identical to the modern political contract theory. It was constituted between tribes and clans, not individuals. But that was the nature of society at that time.” This is true of other religions and societies too, where, for example, women had less rights than men, and which has changed.

The Islamic tradition oscillated between a harmony of faith and reason (seen in philosophers such as al-Kindi and Ibn-Rushd) and coercion and conquest. The centuries have not brought steady progress: in fact, in some ways things have become so backward for so many Muslims that we can be said to be living through an age of unreason. “While premodern Muslims were often confident about their place in the world,” writes Akyol, “the defeats of the modern age, along with real Western intrusions, made many Muslims seek an easy explanation in imagined conspiracies by Western powers and cabals—such as the Elders of Zion.” This anti-Semitic element is powered by “an authoritarianism within” some Muslim societies.

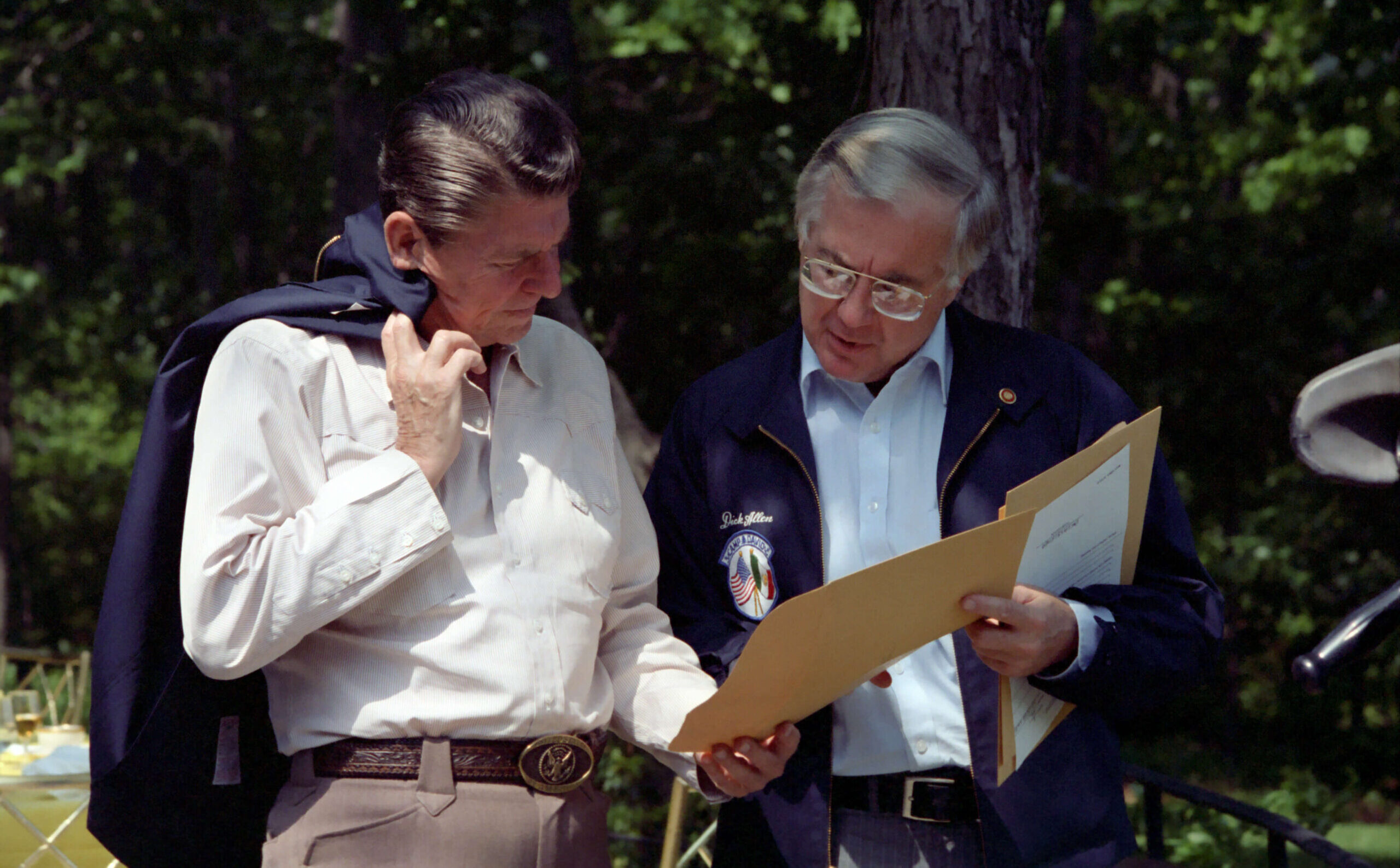

One of the most fascinating chapters in Akyol’s book is on economics and Islam’s insistence on the significance of private property and reasonable taxation. One of the faith’s great scholars of economic theory was Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406), whose philosophy is in certain ways similar to that of Adam Smith. Akyol notes that he was at times quoted by President Ronald Reagan. Ibn Khaldun encouraged economic freedom: “when the incentive to acquire and obtain property is gone, people no longer make efforts to acquire any…. When people no longer do business in order to make a living, and when they cease all gainful activity, the business of civilization slumps, and everything decays.”

There is another side to this “Islamic capitalism.” Like all monotheistic religion, Islam emphasizes charity and compassion in helping the poor. Some Muslims have used this notion to promulgate what Akyol calls “Islamic socialism,” but building a socialist state only creates oppression. Citing a Bosnian intellectual and statesman, Alija Izetbegović, Akyol shows a side of Muslim thinking about economics along similar lines to Milton Friedman’s philosophy of capitalism and freedom. In his book Islam Between East and West, Izetbegović wrote that “socialism and freedom are not compatible… the goal of Islam is not to eliminate riches but to eliminate misery… [this] does not extend to the equalization of property, the moral and economic justification of which is dubious.”

Akyol’s book is an argument for a complete rejection of ideology, especially socialism. Citing an example of Iranian dissidents, Akyol points out that they “aren’t interested in ‘Marxism, post-structuralism, postcolonialism, subaltern studies,’ which have become dominant paradigms in American academia.” Instead, they look to thinkers like, “Isaiah Berlin, Hannah Arendt, and Karl Popper, as well as the Polish philosopher, Leszek Kolakowski, a strong critic of communism.”

Above all, Akyol’s mission in these pages is to persuade Muslim individuals and societies that liberalism as he understands it (which aligns mostly with “classical liberalism” or “libertarianism”) “is not a liberalism that supposedly serves Western imperialism. It is rather native authoritarianism that crushes [Islam’s] liberalism by demonizing it as a conspiracy of Western imperialism.” There is no need to be afraid of reason, he argues. Notions of freedom do exist within Islam, and they require deep exploration and reflection from its adherents. Liberalism is not a rival “religion, metaphysical worldview, or lifestyle in itself,” but instead “a framework that allows” people to be “free of the yoke of all kinds of thugs and tyrants.”

There are of course a wide variety of Muslim cultures. A question that remains at the end of this book is how Islam relates to individual and national identities, and why some Muslim societies permit more freedom than others. Is this because some countries have better “interpretations” of Islam? Or is it because their national identity supersedes the faith itself? Or have they reached a harmony derived from both faith and politics?

Akyol’s approach to his subject is an invitation to dialogue and reflection, both on the personal level and among the larger Muslim community. What matters for him is liberty, because without it human flourishing ceases, and with that comes an age of darkness and alienation.

Emina Melonic is a writer and critic living near Buffalo, New York.