Blue-Collar Conservatism:

Frank Rizzo’s Philadelphia and Populist Politics

By Timothy J. Lombardo

(University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018)

Running for a second term as mayor of Philadelphia in 1975, Frank Rizzo used rhetoric on the campaign trail that was shocking even for the time: he vowed that his method of taking on his adversaries would “make Attila the Hun look like a f-gg-t.” Rizzo suffered no political punishment for language that went far beyond plainspoken, though. He won reelection with 65 percent of the vote, beating his margin of four years earlier. In doing so, University of South Alabama history professor Timothy J. Lombardo argues, Rizzo was a prelude to President Donald J. Trump: a candidate who succeeds despite—or perhaps because of—gleefully breaking taboos. In telling elements of Rizzo’s story, Lombardo also tells the postwar story of his native city and connects white urban Democrats’ voting choice more than four decades ago to the politics of today.

As Lombardo notes, Blue-Collar Conservatism “is not a biography of Frank Rizzo.” Rather, it’s a book about the conditions that made Rizzo possible. The story of Philadelphia is the story of many industrial cities after World War II, but Lombardo adds enough detail to make it unique. Like many cities, from New York under Fiorello LaGuardia to New Orleans under Chep Morrison, Philly went through a midcentury reform era, with liberal New Deal Democrats taking on the urban machines. In 1951, Philadelphians elected good-government mayor Joseph Clark, a wealthy Ivy League WASP who thought the answer to burgeoning stresses—competition from suburbs with backyards, the migration of black southerners escaping Jim Crow, and obsolete manufacturing facilities—was careful technocratic planning.

Some of this planning worked out well and continues to benefit Philly today. In trying to hold on to its tax base, Philadelphia had an advantage many cities lacked: vast tracts of empty land in its northeastern areas. “With industrial relocation, city and economic planners turned a semi-rural city appendage into an indispensable part of the metropolitan economy,” Lombardo writes, with “the relatively empty spaces” nearby “an almost blank canvas for the creation of new urban communities.”

On the commercial side, Philadelphia helped factory owners relocate out of the central city to more modern facilities on the outskirts. This foresight delayed—if not eventually avoided—the hollowing out of working-class and middle-class jobs that debilitated other cities without such room to grow. On the residential side, the city government used federal urban-renewal funds and local planning guidelines to build in a style more akin to British council housing than to American housing projects: row houses that were less dense than inner-city towers, with driveways for cars and green space for children, but still more dense than suburbs. Rather than moving out of the city, tens of thousands of blue-collar Philadelphians—many of them Irish, Italian, and Polish—bought and maintained houses in the northeast.

Shutting Out African Americans

Some of this planning did not work out well, however. Though Philadelphia’s purposeful destruction of its older areas was on a smaller scale than in cities such as New York, it did engage in the type of purported urban renewal whose black victims have long called “Negro removal.” In South Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward, for example, city planners forced two thousand black families to “relocate” in the 1950s to make way for supposedly modern development.

Several forces coincided for ill. Just as the city was displacing thousands of black families, middle-class white residents who could afford to move to nicer neighborhoods did so, leaving deteriorating blocks vulnerable to rapid change. “The establishment of Philadelphia’s renewal and relocation programs also coincided with the rapid growth of Philadelphia’s nonwhite population,” Lombardo writes. During the 1950s, the city’s black population increased by 41 percent, with poorer newcomers settling in already vulnerable areas.

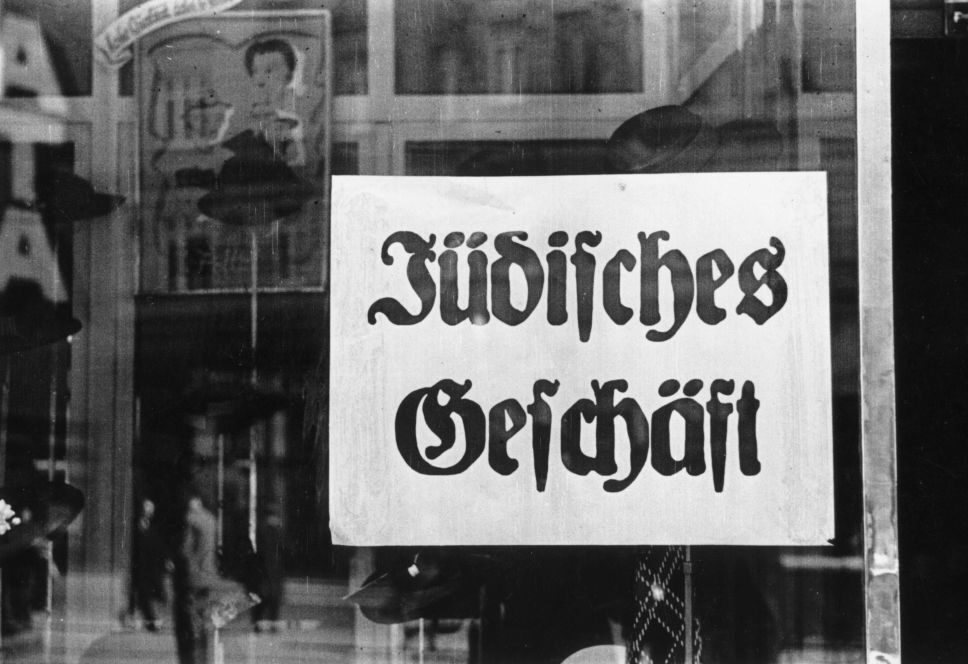

Black Philadelphians were not only shut out of superior housing economically; they were also shut out contractually and physically. Lombardo’s tale is a reminder that in practice if not in law, northern cities often fared no better on integration than the southern states to which their white residents felt superior. In 1959 a real estate agent selling homes in Morrell Park, a new northeast development, testified in a discrimination case that “white homebuyers frequently asked if the development would be racially mixed. . . . They would not purchase a home if African-Americans were permitted to purchase in Morrell Park.” Developers agreed, saying selling homes to black buyers in the area would be “economically unsound.” In older neighborhoods, white residents often responded to new black or Hispanic residents with violence or threats, smashing the windows or conducting mob protests outside property purchased or rented by aspirational newcomers. Lillian Wright, a black mother who attempted to move into Kensington, an older white neighborhood, in 1966, was met with racial slurs and “five increasingly hostile nights of rioting.” She wasn’t alone in this experience.

By the 1960s, racial and economic tensions had reached a crisis point. Like Boston and Charlotte, Philadelphia came under legal and political pressure to bus black public school students into white neighborhoods. (The city said it would not do “reverse busing,” sending white students into black neighborhoods.) Affirmative action in the public sector was roiling traditional blue-collar industries, notably construction. The city also insisted on building traditional public-housing projects in fraying white neighborhoods, exacerbating tensions.

Finally, as in cities from Detroit to Newark, police altercations with the growing black population—including both real and perceived police brutality—led to riots. In August 1964, a black officer and a white officer attempting to mediate a domestic-violence dispute between a drunk couple in a car found themselves under attack, not just from the man involved but also from the residents of neighboring buildings. The attack led to violence and looting that left two people dead and destroyed 118 businesses. This “Columbia Avenue Riot marked a turning point in the city’s racial politics and law-enforcement policy-making,” Lombardo notes. “It shattered the liberal postwar era’s myth of racial progress.”

From Rizzo to Trump?

Enter Frank Rizzo. A high school dropout and Italian American, part of the first generation in his family to be born in America, Rizzo had worked his way up to deputy police commissioner. By the mid-’60s, Rizzo was already a hero within the department, someone who would side with rank-and-file officers over their superiors. By the late 1960s, he had gained a wider reputation, Lombardo writes, by “repeatedly club[bing] young African-American protesters” who maintained a presence outside a school for orphans that had been officially designated as exclusively for white boys by its deceased benefactor’s official request.

“Frank Rizzo’s increasingly visible role in the protests of the mid-to-late 1960s made him a public figure,” Lombardo writes. To wit: Rizzo, fresh from a formal party, once showed up to a white-instigated riot near a public-housing project with a nightstick tucked into his tuxedo. In mid-1967, Mayor James Tate named Rizzo police commissioner. Tate’s staying in office later that year “hinged almost entirely on Frank Rizzo and the politics of law and order,” with Tate pledging during the campaign to keep Rizzo in his position. That year, Philadelphia Magazine ran a profile, calling Rizzo “a tough cop who has never hesitated to jump into a brawl.”

Rizzo’s performance during the unrelenting chaos of the late ’60s and early ’70s further raised his profile. In 1970, “black militant gunmen” ambushed two police officers, killing one. Rizzo carried out an aggressive raid on the armed Black Panthers group ahead of its convention weeks later. Rizzo’s “toughness and unwillingness to compromise in the face of crime and disorder were qualities that endeared him to blue-collar whites,” Lombardo writes, propelling him to the mayoralty a year later. “Supported almost entirely by white, blue-collar voters, Rizzo’s victories signaled changes in white-working-class politics as well as a broader rebuke of an urban liberalism.”

Rizzo’s mayoral record was mixed. He couldn’t save working-class industrial Philadelphia, but probably no one could have. And it might have been worse. “Ironically,” Lombardo notes, Rizzo’s economic-development policies helped remake the city into a reasonably successful white-collar city, “becoming a center of the health care and pharmaceutical industries.”

Rizzo also couldn’t avoid continued racial turmoil. In 1978, a raid on the heavily armed MOVE organization—a racially diverse group suspected of stockpiling bombs—left a police officer dead and led to charges of police brutality. But, again, most likely no one could have prevented such incidents. Similar events plagued New York in the 1970s under liberal mayors.

Rizzo, however, could not resist grandstanding. In 1973, he failed a polygraph he offered to take to disprove corruption, with his supporters blaming “the biased media.” He couldn’t let go of the spotlight either. In 1979, he resorted to outright racial rhetoric in unsuccessfully exhorting supporters to “vote white” to change the city charter to allow him a third consecutive term. In 1991, he died of a heart attack, once again on the campaign trail to regain the mayoralty.

Lombardo is astute to draw a line from Rizzo to Trump. Rizzo’s supporters disdained elitism. Voters repeatedly noted that he was “one of us,” with one Philadelphian, in 1971, saying that “he’ll win because he isn’t a Ph.D.” Rizzo’s supporters became Reagan Democrats and, eventually, some of the swing voters who shocked the elites of both parties by awarding Reagan the key state of Pennsylvania in both 1980 and 1984. “Two decades of navigating the politics of crime, housing, education and employment culminated in blue-collar whites finding more commonality with conservatives than liberals,” Lombardo writes.

Where Lombardo “overdetermines,” to use an academic word, is in ascribing these changes to white working-class and middle-class voters’ alleged failure to see beyond their own parochial anxieties and economic interests, and, in particular, ascribing broad racial motives to both Rizzo and Trump voters. Lombardo writes, for instance, that “blue-collar conservatives did not view the liberal governance of the 1960s as a failure. Instead, blue-collar whites’ selective rejection of liberalism grew out of a belief that liberalism succeeded too well for the wrong people.” This is a startlingly incorrect statement. Few experts today consider public-housing construction that concentrated poverty, forced school busing, and welfare without transition to work to have been successful ideas or to have succeeded for any group, white or black.

In particular, Lombardo thinks any working-class white anxiety about rising crime in the 1960s must have been partly a function of “white privilege,” a phrase he repeatedly uses. For a book whose narrative hinges on crime and a city’s response to it, Blue-Collar Conservatism conspicuously leaves out crime rates, apart from generalities and anecdotes. According to Philadelphia’s own crime statistics, the murder rate tripled between 1960 and 1970. With some significant fluctuation in both directions, murder figures ended the Rizzo years flat.

Crime is and was the result of many factors. But to leave out the spiraling crime rate as a circumstance that would have caused some people to turn to Rizzo, even if they found his personality and racism distasteful, is a significant omission. The real commonality between Rizzo and Trump is an uncomfortable one for an author who would prefer to focus on white privilege. If reasonable people will not—or cannot—deal with what voters see as existential challenges, many voters, perceiving no other option, will choose an unreasonable person to lead them.

Nicole Gelinas is a contributing editor to City Journal.

Founded in 1957 by the great Russell Kirk, Modern Age is the forum for stimulating debate and discussion of the most important ideas of concern to conservatives of all stripes. It plays a vital role in these contentious, confusing times by applying timeless principles to the specific conditions and crises of our age—to what Kirk, in the inaugural issue, called “the great moral and social and political and economic and literary questions of the hour.” Subscribe to Modern Age »