This review appears in the Fall 2019 issue of Modern Age. To subscribe now, go here.

Begin the Begin: R.E.M.’s Early Years

By Robert Dean Lurie

(Verse Chorus Press, 2019)

Robert Dean Lurie acknowledges that the rock band R.E.M., long a critical darling, has been the subject of several books and innumerable articles, but his book Begin the Begin achieves something delightful, even hypnotic. Lurie visits so many of the band’s old haunts and neighbors from Athens, Georgia, that the reader feels almost like a time traveler.

Basement parties, local cranks, between-semester vacations, feuding producers, and band members’ odd jobs all make their appearances here. Photos included are less often of posed rock gods than of detritus such as cheap concert posters and ticket stubs. These details are recognizable to anyone who was on a college campus in the 1980s or 1990s and flesh out a thesis that casual fans might find surprising: R.E.M. is much more a creature of the University of Georgia and 1980s Athens than of “the South” as a whole, despite the band’s broader regional appeal.

Lurie doesn’t expend too many pages trying to justify R.E.M.’s place in the rock canon. Their jangly combination of punk influences with folk and country sounds was a hit precisely because it sounded like modernity constrained by local tradition. Lurie’s book, then, could have been an argument about northern vs. southern rock or about the tension between smart, spooky “alternative” and country-inflected frat music.

Yet Lurie admits that most members of R.E.M. are transplants to the region with which they’re associated. Their southern roots are less like those of a centuries-old tree and more like those of a highway off-ramp. And the pre-R.E.M. bands containing some or all four eventual members produced covers of classic rock groups such as Aerosmith. A big thesis about authenticity wouldn’t work.

Neither would an argument that R.E.M. were destined to become stars. Amusingly for those of us awed by R.E.M. (and who remember them looming large over late ’80s and early ’90s college radio), you get the distinct impression that many Athens residents didn’t think they would be the local band to get famous. More than one local Lurie interviewed says that everyone thought Pylon would be the band to hit it big. Pylon is good but probably now best remembered because R.E.M.’s album Dead Letter Office features a cover of the Pylon song “Crazy.”

Instead, Lurie shows the band working hard but also lucking into some useful connections, including managers used by the rapidly rising Police, one of whose members’ brother, Miles Copeland, founded R.E.M.’s first record label, I.R.S. A third brother, Ian Copeland, had been a runaway, biker gang member, car thief, and volunteer in Vietnam before becoming an influential agent who had a teenage Bill Berry, future R.E.M. drummer, as his talkative chauffeur on a trip to Macon, Georgia, in 1977. The incident made a crucial professional connection and provides a reminder that rock history is mostly happenstance.

What transformed these chance encounters into national and eventually international success was R.E.M.’s unique aura. The band never seemed to be faking it, even as their sound underwent various transformations that happened to make it more arena-friendly than in the early days. It helped that, despite their bohemian presentation, they were always a little pop at heart. Stipe famously claimed he preferred the Monkees to the Beatles. Even Stipe’s distinctive mumbling delivery, we learn, arose as a practical solution to his struggle to recall classic rock songs in his cover-band days. The apparently tortured poet just couldn’t remember the words.

What’s in a Name

One of Lurie’s many fittingly dreamlike asides is the origin of R.E.M.’s name. Those letters do, in other contexts, stand for “rapid eye movement,” and the band members later recalled having stumbled across that phrase in a dictionary. But it appears likely that the direct inspiration was the “R.E.M.” signature that appeared on the photography of a Kentuckian artist named Ralph Eugene Meatyard. Meatyard’s collections cropped up in southeastern college towns around the mid-’70s, depicting old people and neglected places with a clip-art feel not coincidentally like that of R.E.M.’s album covers and videos.

Make your way through the kudzu-like undergrowth of conflicting memories from band members and associates, deliberately provocative statements made to early interviewers, and overly intellectual explanations imposed by wishful critics starting in the 1990s, and you find other quirky yet mundane inspirations in the band’s early days.

Stipe hadn’t emphatically identified as gay, but he did take great comfort from the 1975 Samuel R. Delany sci-fi novel Dhalgren, which depicts a future in which all sexual taboos and central authority have eroded. Patti Smith was also an inspiration and in retrospect influenced his androgynous look. It may have helped that she preceded punk and was more poet than rocker at heart—succeeding despite embodying an artistic ambivalence similar to that of the young Stipe, who the other R.E.M. members worried would not be willing to give up visual arts or leave college even after the band formed.

Becoming a rock band, after all, was and is not an obviously safe career choice. It is amazing any famous band made its way to us intact through the random obstacle course of history. In R.E.M.’s case, the call of responsible but boring jobs was always there. Bassist Mike Mills briefly worked at Sears right after high school. Drummer Bill Berry was keen to rock but planned to become a farmer—an ambition he has pursued since the band broke up.

Luckily for us all, R.E.M. made its way into a Smyrna, Georgia, studio by 1981. “Over the course of one day,” writes Lurie, “they recorded live in-studio versions of ‘Sitting Still,’ ‘Gardening at Night,’ ‘Radio Free Europe,’ ‘Shaking Through,’ ‘Mystery to Me,’ ‘Don’t Go Back to Rockville,’ ‘Narrator,’ and ‘White Tornado.’ ” In contrast to the happenstance of the early years, there was an almost plodding quality to their rise thereafter—appearing on David Letterman’s show in 1983 to perform “Radio Free Europe” and following up with “So. Central Rain” before the song had even been given a name. I remember seeing that appearance as a kid and thinking the band was great but also knowing intuitively it might take a little extra effort to hear more of their stuff. You never felt confident they’d find their way into the Top 40, and that was a good thing. It created mystique and loyalty.

They Knew Them When

To those of us dwelling in the college-rock ghetto just after New Wave receded but before grunge steamrollered its way into popular music, R.E.M. were unassuming, low-key gods. Lurie mainly captures the band just before they reached that stature, when neither they nor their Athens peers could be certain R.E.M. would attain fame of either the niche-hipster kind or the arena-rocking kind. That period of protracted ambiguity may have helped keep them human. For a few years to come, other Athenians would still know where the band members’ houses were located.

This book is defined by that familiar, slightly shambolic quality. Lurie, who went to the University of Georgia himself about a decade and a half after the members of R.E.M., is able to walk the streets of Athens in an unhurried way, talking to local cranks, amateur historians, music obsessives, and longtime neighbors. The effect is almost like a meandering walking tour not just of the place but of the R.E.M. members’ personal pasts, with the weird juxtaposition of the historically significant and the trivial that walking tours tend to have. That might not be what a serious music critic is looking for in a book on R.E.M.—and Lurie happily cites several books that have covered the more serious critical ground already—but it may be exactly the kind of dreamy, poetic, yet everyday intimacy many R.E.M. fans adore. Lurie notes that a decaying train trestle in the area has spawned a movement of preservationists who want it declared a landmark because it appears on one of those ancient-seeming, clip-art-like R.E.M. album cover montages. But it’s just an overgrown train trestle, insist the locals, and there are dozens of them all over the South.

That’s the magic of R.E.M. Without seeming to exert the slightest effort, they create the impression they’re alluding to a lost past more important than the real one, even though their imagined one is mostly indistinct and maybe rather ordinary when it comes into focus. The effect is a little like pleasantly trying to remember a dream upon waking even though you aren’t for a moment convinced the dream was shocking or vivid. Begin the Begin is a lot like that. ♦

Todd Seavey is a Splice Today columnist and author of Libertarianism for Beginners.

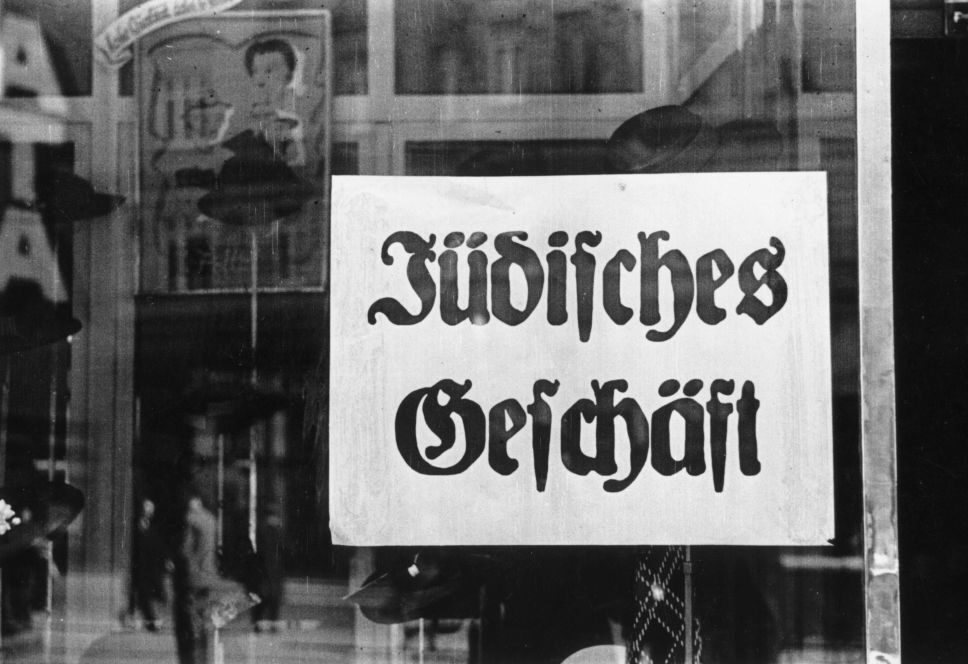

Founded in 1957 by the great Russell Kirk, Modern Age is the forum for stimulating debate and discussion of the most important ideas of concern to conservatives of all stripes. It plays a vital role in these contentious, confusing times by applying timeless principles to the specific conditions and crises of our age—to what Kirk, in the inaugural issue, called “the great moral and social and political and economic and literary questions of the hour.”

Subscribe to Modern Age »