US Grand Strategy in the 21st Century: The Case for Restraint

Edited by A. Trevor Thrall and Benjamin H. Friedman

(Routledge, 2018)

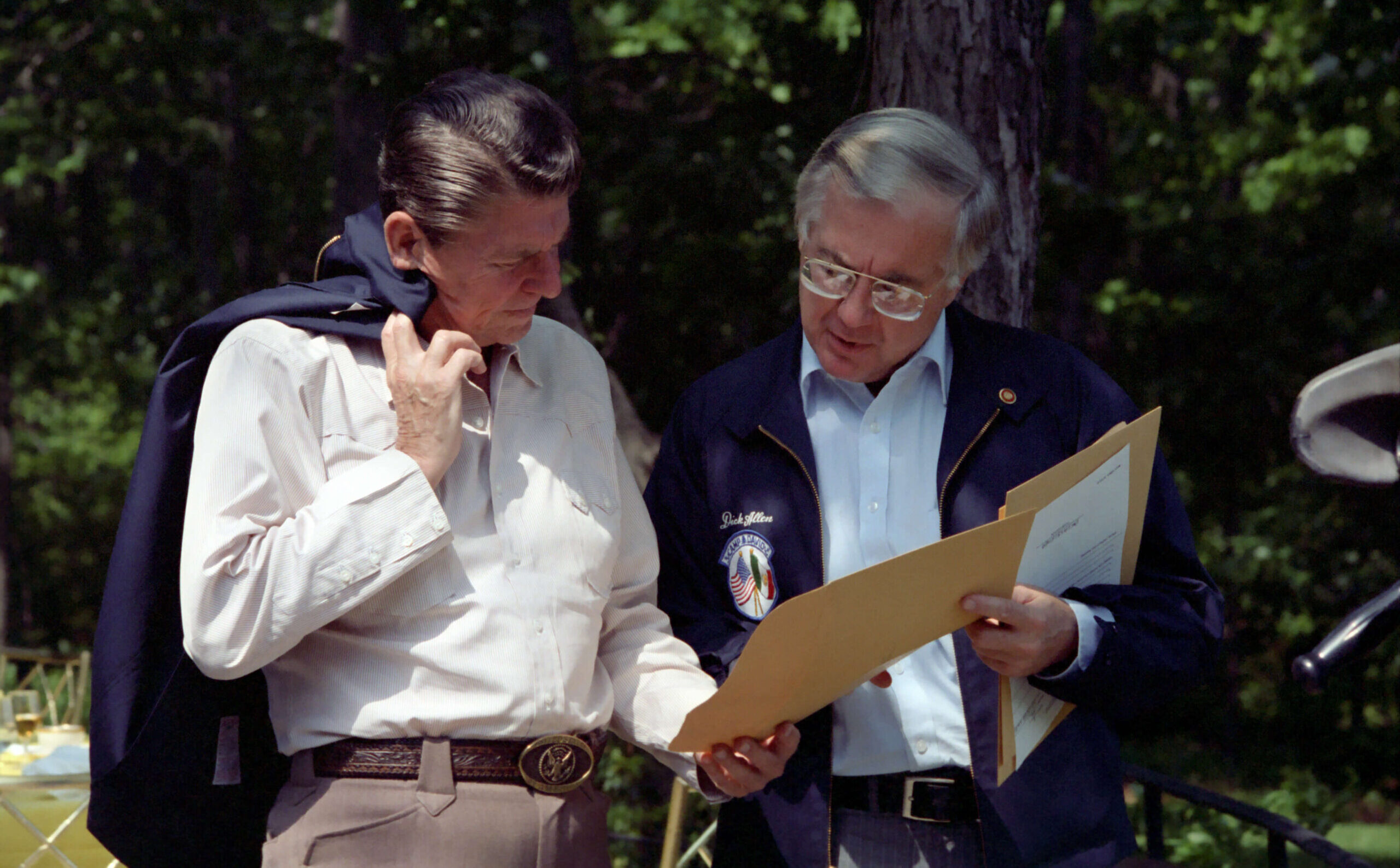

Early every spring, I discuss Ronald Reagan’s 1982 address to the House of Commons in my introductory American history course. When Reagan delivered this speech more than thirty-five years ago, Leonid Brezhnev presided over the Soviet Union, the Solidarity Movement was rocking Poland, the Berlin Wall still stood, and Britain fought Argentina to retain control of the Falklands. In the midst of turmoil, there was something noble about Reagan’s aspirations for the advancement of freedom and democracy. And there is much to be thankful for in the fact that the Cold War ended and Marxism-Leninism was consigned to the “ash heap of history.”

But one of Reagan’s most sweeping claims no longer rings true in the light of experience. Since 9/11, the United States has learned some harsh realities about what some peoples around the world aspire to achieve. “It would be cultural condescension, or worse,” Reagan claimed a generation ago, “to say that any people prefer dictatorship to democracy. Who would voluntarily choose not to have the right to vote, decide to purchase government propaganda handouts instead of independent newspapers, prefer government- to worker-controlled unions, opt for land to be owned by the state instead of those who till it, want government repression of religious liberty, a single political party instead of a free choice, a rigid cultural orthodoxy instead of democratic tolerance and diversity?”

Words meant to express a self-evident truth of human nature now seem contradicted by harsh reality. They may be metaphysically true, but policymakers have to deal with the world as it is—not, as Lyndon Johnson said, so we can make it into what we imagine it ought to be but simply because the statesman’s first responsibility is to secure the peace, safety, and prosperity of his own nation. There are people, in the millions today, who would gladly suppress religious liberty, a free press, and multiparty rule, and exchange tolerance and diversity for “a rigid cultural orthodoxy.” Perhaps they are wrong to do so—but they would do it all the same.

Reagan does not appear in US Grand Strategy in the 21st Century, but it is hard not to think of his hopes for the advancement of democracy and freedom when reading the book. If such an ideal continues into the twenty-first century and continues to shape U.S. policy, on what is its optimism based? Is it based on a realistic assessment of the capacity of the nation and its military to remake the world? Is it based on proven experience with forcible regime change over the past century? Is it consistent with America’s history, traditions, and institutions? The sobering answer offered in this welcome collection is that there is little on which to ground the aspirations of progressive imperialism and America’s foreign-policy idealism—little, that is, in the record of success in spreading and sustaining democratic regimes, and little in American history before its plunge into empire in 1898, to prove that the U.S. ought to be and was meant to be a “dangerous nation,” in Robert Kagan’s mischievous phrase.

Together the dozen essays in this book make a strong “case for restraint” as America’s grand strategy. They ask the right questions, provide a framework within which to rethink U.S. foreign policy, and propose alternatives to a strategy that has proved costly and unsustainable. The editors begin with an overview of the arguments for restraint over against the bipartisan consensus around “primacy” and “liberal hegemony.” First, restraint makes good policy because the United States “faces limited threats to its national security thanks to its geographic, economic, and military advantages.” Second, restraint lowers the staggering costs of global intervention and supports a more flexible foreign policy with greater freedom of choice. Third, restraint recovers “the classical liberal tradition of the nation’s founding.” The editors and contributors do not hesitate to return to principles long out of fashion: independence, nonintervention, avoidance of entangling alliances, and free trade. They also look for wisdom to such equally unfashionable documents as Washington’s Farewell Address, John Quincy Adams’s warning against ideological crusades, the Monroe Doctrine, and a host of lesser-known statements of what amounted to a foreign-policy orthodoxy in the old Americanism.

Part I of this collection lays out “the case against the strategy of primacy.” Anyone skeptical of America’s capacity for successful nation building and democracy building has to answer the obvious (and often angry) objection that the United States successfully remade two defeated nations in the twentieth century. But what if post–World War II Germany and Japan turn out to be the exceptions that prove the rule? This is the case made in the essay by Alexander B. Downes and Jonathan Monten. When the United States contemplates regime change, it is only a democratic regime that it imagines imposing. This means that the wisdom or folly of nation building rests on the capacity of democratic institutions to be planted and sustained in a particular place, among a particular people and culture. The authors analyze a large number of attempts at democratic regime change in the twentieth century. The obstacles to success are sobering. Democratic institutions are difficult to impose where there is a low level of economic development; where there is pronounced “ethnic, linguistic, and religious diversity”; where there is little or no historical “experience with representative government”; and where the act of intervention itself is likely to promote civil war among factions. Democracy is hard work. Constitutionalism is even harder work. Institutions have to be built and maintained. They take time, and they depend on the habits of the people and their leaders.

Absent one or more of these preconditions, is it any wonder that Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, and Libya are mired in violence? The authors follow their data where it leads them, and they hold out the possibility, albeit a slim one, that regime change can work where the preconditions are met. But they remain skeptical. How often can these preconditions be met? A century of experience shows that “democracy is unlikely to take root” in weak states—the very places in which democratization is currently being attempted by the United States.

In contrast to the current bipartisan strategy of primacy, nineteenth-century America looks like an ancient civilization or a lost world. The discontinuities are striking, and the essays by William Ruger and Edward Rhodes show just how much has changed. Ruger’s title, “Not So Dangerous Nation,” takes direct aim at Robert Kagan’s thesis in Dangerous Nation that the United States has always and by design been a threat to tyrannical regimes. Supposedly there has been ideological continuity across American history and not a major turning from an “Old Testament” of self-restraint to a “New Testament” of expansive intervention (to borrow Walter A. McDougall’s effective metaphor). Ruger is correct to note that “liberal interventionists have always been among us,” but he knows that those arguments were kept in check by a policy of “strategic independence” and “military non-intervention.” Beginning with Thomas Paine, whose insistence that America stay far away from Europe’s troubles comes as a surprise in light of his radicalism, Ruger shows the consistency across administrations of a strategic orthodoxy committed to neutrality, noninterference, no entangling alliances, peace, and commerce; fear of standing armies and a bloated military; and worry about what an aggressive foreign policy would do to domestic liberty and the vulnerable institutions of limited and representative government.

Rhodes for his part calls Kagan’s case for a precedent for progressive imperialism in the early republic “fundamentally anachronistic,” but at the same time he makes a compelling case for the presence of two conflicting “visions” in American history since the eighteenth century—the liberal tradition exemplified by John Quincy Adams and the republican tradition exemplified by Theodore Roosevelt. Both men asked what kind of foreign policy was necessary to sustain a liberal republic. Adams answered that it required restraint, nonentanglement, and avoiding crusades “in search of monsters to destroy.” Roosevelt, like Henry Cabot Lodge, Walter Hines Page, and other expansionists, feared that the ease and wealth produced by industrialization and classical liberalism threatened to make the nation effeminate and rob it of the courage, fortitude, and daring that make peoples truly great. Rhodes’s most important point is that both Adams’s restraint and TR’s progressive imperialism were conscious choices and not inevitable or a matter simply of logic or necessity.

This gets to the heart of Kagan’s error. His case for America’s identity as a “dangerous nation” mistakes the general public’s enthusiasm for revolutionary movements in the nineteenth century for principles of American foreign policy. Support for South American republics, Greece, Poland, Hungary, and Italy was at times passionate. But the significant thing is that the U.S. government did not act on this romantic zeal to aid independence movements. Private citizens sometimes did. They might host foreign exiles in their homes, wine and dine them at banquets in their honor, give them a public forum, raise money for their cause and provide relief for refugees, name streets and towns after them, and even volunteer to serve in their wars of liberation. But the U.S. government did not mobilize its army and navy to guarantee the success of these independence and national consolidation movements.

This obvious but neglected truth was pointed out more than forty years ago by Rush Welter in The Mind of America. Welter is worth quoting at length. In effect, he answered Kagan decades before Kagan wrote. “If Americanism connoted loyalty to the United States in order to further the cause of liberty at home, the mission of America came down to much the same thing with respect to liberty in the rest of the world.” That is to say, America would do the most for liberty in the world by attending to liberty at home. “Reading American expressions of foreign obligations uncritically, historians have implied that nineteenth-century speakers who invoked images of a world mission for the United States intended thereby to express the kind of foreign-policy commitment that Woodrow Wilson was to voice so eloquently in 1917 and 1918.” Precisely. This is what Kagan does, and where Ruger and Rhodes provide an important corrective. Discovering dubious precursors in the nineteenth century for an aggressive U.S. foreign policy in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, Kagan plunges into the very historical confusion that, with a little care, he could have avoided. But he never meant to avoid that confusion. His goal was to prove that contemporary interventionism is in fact authentic to the whole American tradition—a fulfilment rather than a betrayal of what America owes the world and itself.

The moment American foreign policymakers started asking why we can’t be more like Europe is the moment the United States lost its exceptionalism. The empires of Europe, especially Britain, became models of national greatness to imitate. Incensed by Grover Cleveland’s “blundering foreign policy” and embarrassed by the mundane ambitions of classical liberals, Henry Cabot Lodge argued for a transformation in U.S. policy in keeping with the manifest direction of history. “The great nations are rapidly absorbing for their future expansion and their present defence all the waste places of the earth,” he wrote. “It is a movement which makes for civilization and the advancement of the race. As one of the great nations of the world, the United States must not fall out of the line of march.”

Perhaps what ultimately divides restraint from primacy, whether in 1898 or today, are competing conceptions of national greatness. If “making America great again” leads to a reaffirmation of global democracy, regime change, and nation building, then the skeptics, realists, and advocates of restraint among us will face a daunting challenge as they try to articulate alternatives.

Three years into the Trump presidency, we can at least say that the language used by the White House to justify U.S. action in the world has changed. In contrast to most of the Republican contenders in 2016, Trump did not sell himself as the Second Coming of Ronald Reagan. As president, he has never described America as a “city on a hill” to promote any foreign or domestic policy. That metaphor—once ubiquitous among Republicans and favored by more than a few Democrats—has been retired after sixty years of service. It may not yet have been consigned to the ash heap of history, but for now at least U.S. strategy does not speak the language of neo-Wilsonianism, Kaganesque progressive imperialism, or even Reaganesque global democratic revolution. The task facing advocates of strategic restraint is to capture the American imagination with a compelling new vision. This book contributes to that effort by providing a calm and sobering assessment of America’s prospects for remaking the world in its own image and offering resources for a renewal of the nation’s formative traditions. ♦

Richard M. Gamble is professor of history at Hillsdale College.

Founded in 1957 by the great Russell Kirk, Modern Age is the forum for stimulating debate and discussion of the most important ideas of concern to conservatives of all stripes. It plays a vital role in these contentious, confusing times by applying timeless principles to the specific conditions and crises of our age—to what Kirk, in the inaugural issue, called “the great moral and social and political and economic and literary questions of the hour.”

Subscribe to Modern Age »