Docilitas: On Teaching and Being Taught

By James V. Schall

(St. Augustine’s Press, 2016)

On the Unseriousness of Human Affairs:

Teaching, Writing, Playing, Believing, Lecturing, Philosophizing, Singing, Dancing

By James V. Schall

(ISI Books, 2001)

The best teachers may not be alive when we are. We may teach those who do not yet exist, or those who do exist but whom we shall never meet. Yet teaching depends on presence. Books make present him who is long dead, who is far away, who speaks a language not our own, yet who is human as we are. —James V. Schall, Docilitas, 27

The “radical” nature of this book, the essence of which is emphasized by the centrality of the word “unserious,” is the effort to reaffirm the truth of the central tradition of our culture: man is not the highest thing in existence even though his being, as such, is good—and it is good to be. Recognizing this truth does not lessen human dignity but enhances it. —James V. Schall, Unseriousness, xii

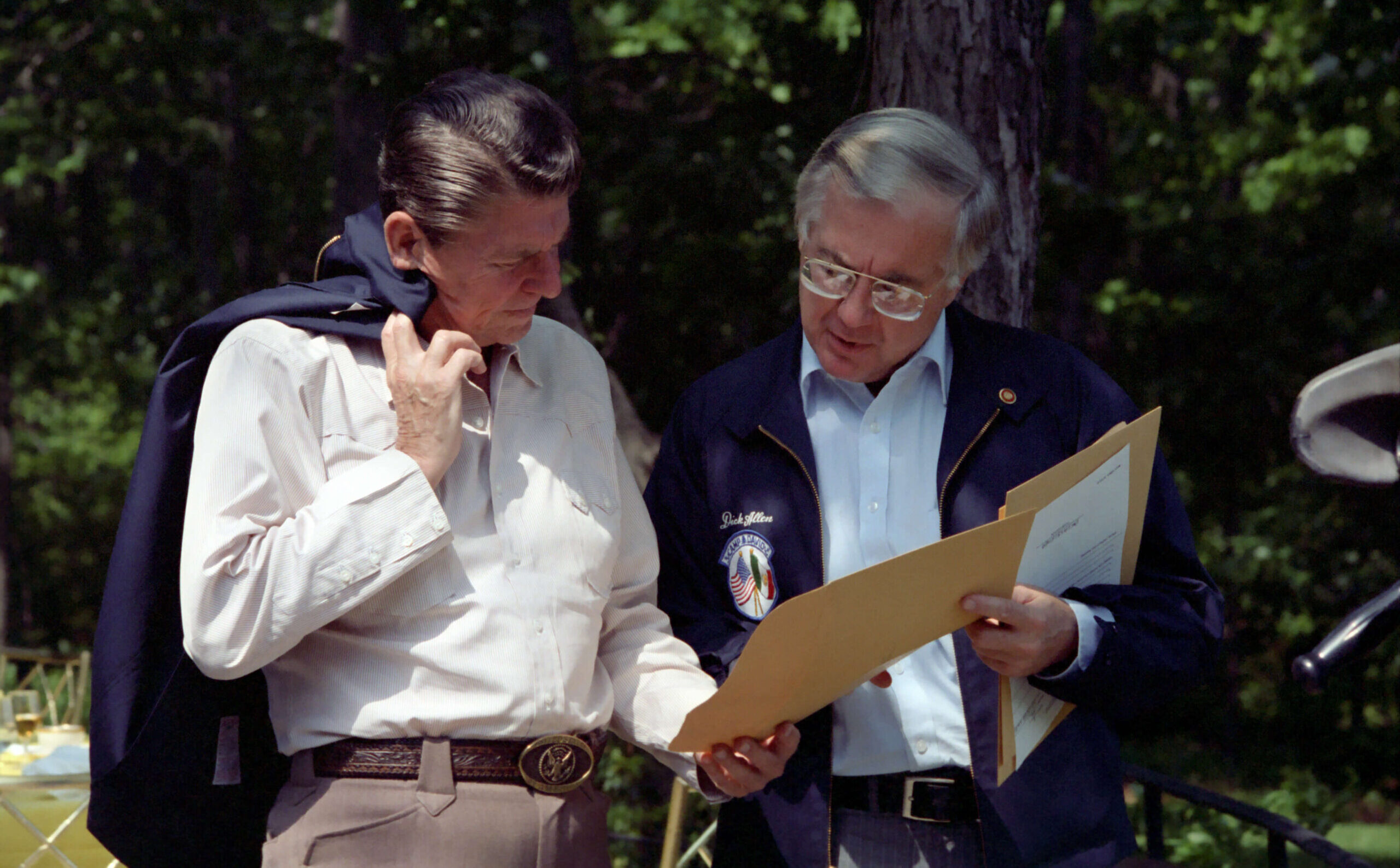

James V. Schall characteristically introduces his essays and book chapters with quotes he takes from authorities, which shine a light on his purpose and argument and also situate his own writing in the context of the great thinkers from whom he has learned. The teacher always hands on what he himself has learned from his own contemplative activities and from those who have aided him to know what he now knows. Schall is a great—even legendary—teacher. His valedictory lecture on “The Final Gladness” at Georgetown upon his retirement from teaching there drew seven hundred undergraduates, former students, friends, and luminaries from academia and politics to Georgetown’s Gaston Hall in 2012. He has taught thousands of students directly in his classes over his teaching career, which spans six decades. For those of us who were never able to take a class from him, we can have recourse to his countless published essays and his more than forty books, which, as Schall says, make him present to us even though he is far away. For those of us who are teachers, we fortunately have recourse to Schall’s books on teaching.

Schall’s understanding of teaching and learning is distinctly countercultural. For example, the common view of students entering college as freshmen, as well as of most university administrators, is that the professor acts as a deliverer of content. The professor possesses information, which he then downloads into his students. His students in turn reproduce that information so the professor can evaluate what the student has learned and the university quality-control administrator can finally evaluate the professor’s teaching effectiveness. Professors are employed on the basis of their ability to convey information to students efficiently, effectively, and in as high a volume as possible. Students pay tuition on this basis as well, as consumers of academic product: the information that professors deliver to them that will allow them to get jobs and advance in them. At its more elevated levels, this model of teaching and learning can include mental skills like critical thinking that can be applied in many different employment settings. The ritual of the student evaluation is supposed to present to the university administration data on consumer satisfaction.

For Schall, the model of the teachers’ function sketched above is deeply flawed from its principles, because “what they teach, if true, is not theirs. They do not own it. They did not make it or make it to be true.” As a result, “any financial arrangement with a true teacher (I do not here mean just anyone employed by a school system) is not a salary or a wage but an ‘honorarium,’ something offered merely to keep the teacher alive, not to ‘pay’ him for ownership of a segment of ‘truth’ said to be exclusively his” (Unseriousness, 64). Those who, like the sophists, charge for what they teach, for their special knowledge or their expertise, implicitly claim either that they possess for themselves the knowledge they claim to pass on to the student, or that there is some kind of method that is proprietary and in their control, or that truth is something that is made by man, not discovered as already existing (our word fact, which is almost identical with what we mean by truth nowadays, comes from the Latin word factum, which means “made”). Schall’s position is therefore in the long tradition of Socrates, who claimed to be only a midwife of learning and not a teacher, and of St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, for whom the only true teacher was the truth itself. The human teacher is therefore only a teacher in an extended sense.

Schall’s critique of the currently dominant model of teaching and learning leads directly to his critique of the entire anthropological and even metaphysical basis on which it is founded. This is why Schall says that human affairs are “unserious”: because we are not the highest things, and we exist already in a relationship to higher things. He points out, “The highest things, including ourselves, are given to us; we do not make them to be what they are” (Unseriousness, 153). Our desire to know those things is what constitutes our being at its highest level. We desire to know naturally, and we desire to know the highest things most of all. Further, we are really capable of knowing those things. He says, “We are in principle not confined to ourselves. Nor do we want to be. We are beings who want to be related to all that is not ourselves. If we look at this fact about ourselves, we come to realize not only are we related to all things that are but we are related to those beings which are likewise related to all that is” (Docilitas, 23). Schall never tires of using the Thomistic phrase describing our minds capax omnium, capable of all things.

Even more, our desire to learn, to “be related to all that is not ourselves,” has an outward drive: we find, once we have come to know something, that we also desire to share what we know. The student desires to learn and the teacher desires a pupil with whom he can share what he has learned. Schall observes, “What does it mean ‘to teach’? Teaching is correlative to learning. In the end, the successful teacher and the successful pupil know the same truth, which neither of them owns and to which both are subservient” (Docilitas, 27). Knowledge of the truth, when unfettered by pride or other vices, leads naturally to friendship, since the truth is a common good that can be shared without being diminished.

One of the effects of the shift to an understanding of students as consumers has been to shift the entire, or nearly the entire, burden of learning onto the teacher. Because the customer is always right, the exigencies of the higher educational market increasingly demand accountability on the part of the professor, while decreasingly demanding accountability on the part of the student. Professors and serious students will, for that reason, be gratified to find that Schall affirms that students have obligations to their professors, foremost among which is the student’s capacity and willingness to be taught—his “teachability,” or docilitas in Latin. To explain this unfashionable virtue, Schall says, “The virtue of ‘docility’ asks: ‘Are we capable of being taught by all things, especially by the highest things?’ In the end, we stress the ‘being capable of being taught,’ rather than the ability to teach, though that too is a fine art” (Docilitas, 191). If docility or teachability is a virtue, then it also has its proper obstacles. A great deal of Schall’s writing on teaching is dedicated to unveiling these obstacles.

The first obstacle to learning, Schall says, is internal and is what the liberal arts are originally supposed to address. The liberation that the liberal arts are supposed to bring about does not issue into, as Schall says, freedom as a “power to make things, including ourselves, to be otherwise, to restructure the state, the family, the inner soul. Rather it is the liberty to affirm and follow what we are wherein what we are is not something we make or define, but what we discover ourselves to be” (Docilitas, 100). The liberal arts are supposed to free us from the tyrannical desire to be the source of truth or for the truth to match our desires. These desires are what Plato and Aristotle, each in his own key, regarded as excessive attachment to one’s own, and what the Christian tradition called pride.

The second obstacle is related to the first: lack of discipline and corresponding lack of an order to study. If I regard myself as the source of truth, there is no need for disciplined self-mastery; there is no need to adjust myself in line with what exists outside myself. If there is no truth outside myself, then there is no transcendent order that demands either my attention or implies the right way—and corresponding wrong ways—to come to know it. As Schall says, “To learn something, we have to be internally free to do so. We need especially to be free from ourselves, from the notion that what ‘I want’ is the most important thing about us” (Docilitas, 11). Schall recognizes that I am most at peace with myself and most free to learn when my desires match up with the objective order of what is. When my desires are not oriented by what is, I am a slave to them because they prevent my wanting to know the truth, which might conflict with what I want and might require me to change the way I live my life. Schall points out with a reference to Plato:

In the seventh of his Letters, Plato advises that the best way to find out if an intelligent young tyrant—all potential philosophers are also potential tyrants—was really interested in knowing the truth is to explain to him how much he has to sacrifice in terms of hours of work, singular devotion, poverty, and ridicule in order to be a true philosopher. Our universities, no doubt, are full of young men and women, potential philosophers all, who like the rich young man in the Gospels turn and go away sadly when they find what they must do to be good, to be perfect, to know the truth. (Unseriousness, 35)

The truth makes difficult demands on its devotees.

The lack of confidence that there is an order to reality that transcends me and exists independently of me has its institutional expression in the chaos that is the modern university curriculum. If there is no discernible order in reality, or at least none that can be known, then there can be no order in learning other than the order imposed by power for purposes other than the love of wisdom—to get a job, to raise consciousness, to advance the cause of social justice, etc. But what happens most often is that the material students are presented with is just a maelstrom of randomly collected subject matter, which, as Schall remarks, presents serious pedagogical challenges: “Much of our difficulty in provoking students to learn, I think, arises precisely from the sense of loathing and confusion that naturally arises when they are confronted, as they usually are, with a mass of unrelated material” (Unseriousness, 23). The contemporary situation universities find themselves in has the effect of reducing what is taught there to trivia. If the curriculum itself does not present a case for its content and structure, then students will not care about it. The question, or similar questions, about “How will this help me get into medical school?” is always ready to hand. But the curriculum will not be able to make such a case if the university, as an institution, does not affirm that it is a good thing to seek knowledge about the order of reality, which itself must include at least the suspicion that there is an order to reality. “If our philosophic presuppositions, in effect, allow no answers to any questions,” Schall emphasizes, “we cannot have a university, only a debating society that allows no verdict” (Docilitas, 41).

The university itself, Schall thinks, ought to be a place of contemplation. Concerns about the world that surrounds students ought to be put on hold during this privileged time. Truth does not follow fashion, and real learning can take place only in a setting undisturbed by the urgency of practical action. Paradoxically, however, that lack of concern for practical effectiveness can be most effective. The course of St. Augustine’s life, for example, was entirely changed by his encounter with one book by Cicero, the Hortensius, which convinced Augustine that he should try to become a philosopher. And because the course of Augustine’s life was changed by that book by Cicero, the course of the world was changed, too.

Schall constantly points his readers and his students to the reading of great books by great thinkers. He most often refers to Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, Aquinas, Pascal, and Samuel Johnson. But he also resists the fetishization of the great books or their treatment as magical talismans. Instead we ought to regard those classic books as teachers that are still in some way our contemporaries. “The classic books and the ideas that flow out of them are capable of being assimilated in the soul of anyone who thinks his way through them.” When we read them, they can also read us and allow us to see things about ourselves that remain invisible otherwise. For instance, “We should try to see that Socrates speaks to the trouble in our own souls. We should realize that Socrates is still teaching us” (Unseriousness, 118). Knowledge of a text, even a great one, cannot constitute wisdom. The point of great texts is to teach, not about themselves, but about reality and how their readers fit into reality.

Even so, Schall says, it may be that we do not have time even in a whole life to master even one of the great books. The job of the teacher, especially one who teaches young students, is not to raise his students to the level of mastery of the books he teaches, but “to facilitate the first reading of his students without which a second one is not metaphysically possible or, often humanly speaking, likely” (Docilitas, 43). As with any hard task, making a start is often the most difficult step and reading a great book only once is most certainly just making a start. Reading a great book can be a thrilling experience on the first attempt, but it can also be dry or confusing and frustrating. For most students, it is more likely to be the latter. If they are not exhorted, cajoled, charmed, or even coerced and bullied into making a start, there is no possibility they will come back and reread. Schall observes that this means that a course is sometimes not completed until years after, if at all, “if [the student] is still pondering, remembering, and re-reading what he had once read and considered” (Docilitas, 45). That can be an encouraging thought for the professor, especially one burdened by academia’s own “hot take,” the student evaluation.

No essay on the thought of James V. Schall is complete without a consideration of the place of divine revelation. It is revelation, Schall thinks, that holds out the hope that the human task of learning might be completed. The desire for and necessity of revelation, Schall says, arises out of the nature and task of philosophy and science, which are always searching and always lacking the perfection they seek. He says,

Revelation does not replace philosophy or science. Yet the very fact that they do not complete themselves leads to a certain wonder if their completion is addressed to us in another way. It is not “outside” of rational research that its limits are found, but within them. . . . There may be a “way” to the “completion of truth.” We can choose to close off this way, no doubt, but that very closing off would itself be a sin against the light of the mind itself. (Docilitas, 58)

Schall’s understanding of the relationship between reason and revelation points to a higher kind of docilitas the student needs: a capacity and willingness to be taught about the very highest things, to which science and even philosophy cannot themselves attain on their own. ♦

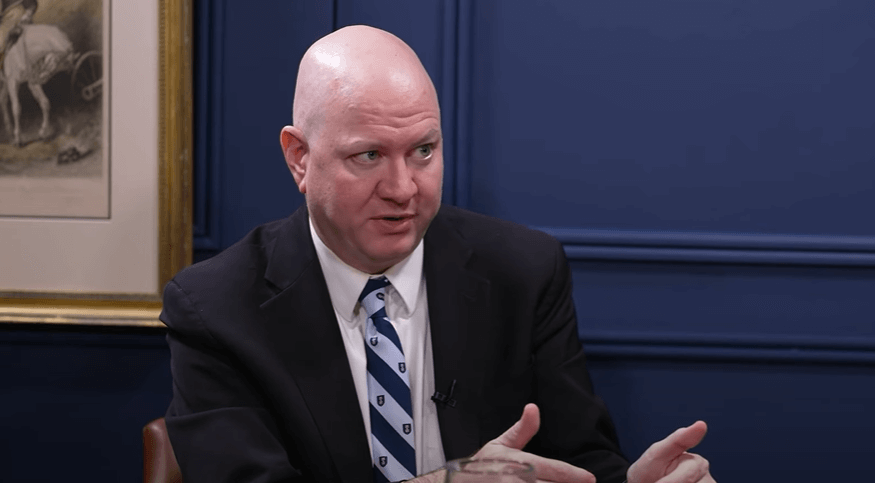

Thomas P. Harmon is dean of humanities at John Paul the Great Catholic University in Escondido, California.