As Americans look forward to celebrating Independence Day, some on the right harbor reservations about the great national holiday’s meaning. The doubters may still enjoy the Fourth of July, but they find fault with the Declaration of Independence and the philosophy expressed in its powerful words. They have reasons for their skepticism—yet there are better reasons for rejecting it.

One could argue that celebrating the nation’s independence is not the same as accepting the self-evident truths announced in the Declaration of Independence—which is in fact the position taken by some conservatives. There are, at least on the right, two main arguments against the centrality of the Lockean natural rights language we find in the Declaration. The first disputes that those theoretical ideas are essential to understanding the goals and principles of the founding. This argument downplays John Locke specifically and social compact theory more generally. Paleoconservatives and traditionalists prefer to emphasize the continuity of American republicanism with long-standing English liberties. Some go so far as to deny that the founding was a “revolution” at all.

The second line of criticism accepts that Locke’s ideas were at the heart of the founding but thinks these reveal the weakness, rather than the strength, of the American regime. According to this view, the degraded condition of today’s egalitarian, hedonistic society, awash in pornography and shallow commercialism, is the direct consequence of the founders’ regrettable emphasis on the “liberal” doctrines of equality and natural rights.

Harry Jaffa devoted decades to refuting these claims and defending what he called “the moral realism and natural theology” of the Declaration. Jaffa is mostly known as a Lincoln scholar (especially for his landmark 1959 book on the Lincoln–Douglas debates, Crisis of the House Divided). But he also wrote several books about the American founding and how conservatives should understand it, including Equality and Liberty (1965), How to Think About the American Revolution (1978) and American Conservatism and the American Founding (1984).

He emphasized (against the traditionalists and paleoconservatives) that Lockean social compact theory is not only essential to the proper understanding of the founding but also eminently conservative. At the same time, he disputed the claims of the so-called “East Coast Straussians” who—like many of today’s Catholic integralists—believed that the founders’ emphasis on equal rights led to our contemporary degradation.

Virtually everything that is wrong with the United States today can be traced to the rejection of the founders’ natural rights philosophy.

The historical and documentary evidence assembled by Jaffa shows—convincingly, I think—that intellectuals on the right should join the millions of ordinary American citizens who celebrate the Declaration of Independence. (Isn’t acknowledging the good sense of the people conservative too?)

Let’s start with the first claim about Lockean natural rights. Jaffa has shown that when we examine the founders’ letters, speeches, proclamations, and resolutions, we find that in their disputes with the British king and parliament the colonists did indeed defend their traditional privileges as Englishmen until about 1775. But by 1776 they had gradually come to see themselves as a separate people—Americans, rather than subjects of the British empire. Concluding that a complete separation was necessary to secure their liberty, they began to adopt more radical arguments. Drawing on authors such as Locke and Thomas Paine, their arguments and rhetoric then turned decisively to emphasizing the natural equality and individual rights the Americans possess as human beings. (If they no longer considered themselves British subjects, how could they continue to appeal to their rights as Englishmen?)

America’s political leaders, clergy, and even common citizens came to reject not just the authority of King George but also divine-right monarchy as such, because they saw political authority as grounded in the sovereignty of the people, who establish legitimate government on the basis of consent.

What’s the evidence for this? First and foremost, of course, is the Declaration itself, signed on July 4, 1776, by no fewer than fifty-six delegates to the Continental Congress, representing every state. That includes the famously “sober” John Adams, who actually served on the drafting committee. When the Declaration was signed, John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress, immediately sent a copy to General George Washington, who had it read aloud to his troops on July 9, 1776. The Declaration was then and thereafter understood as the document explaining the principles of the Revolution.

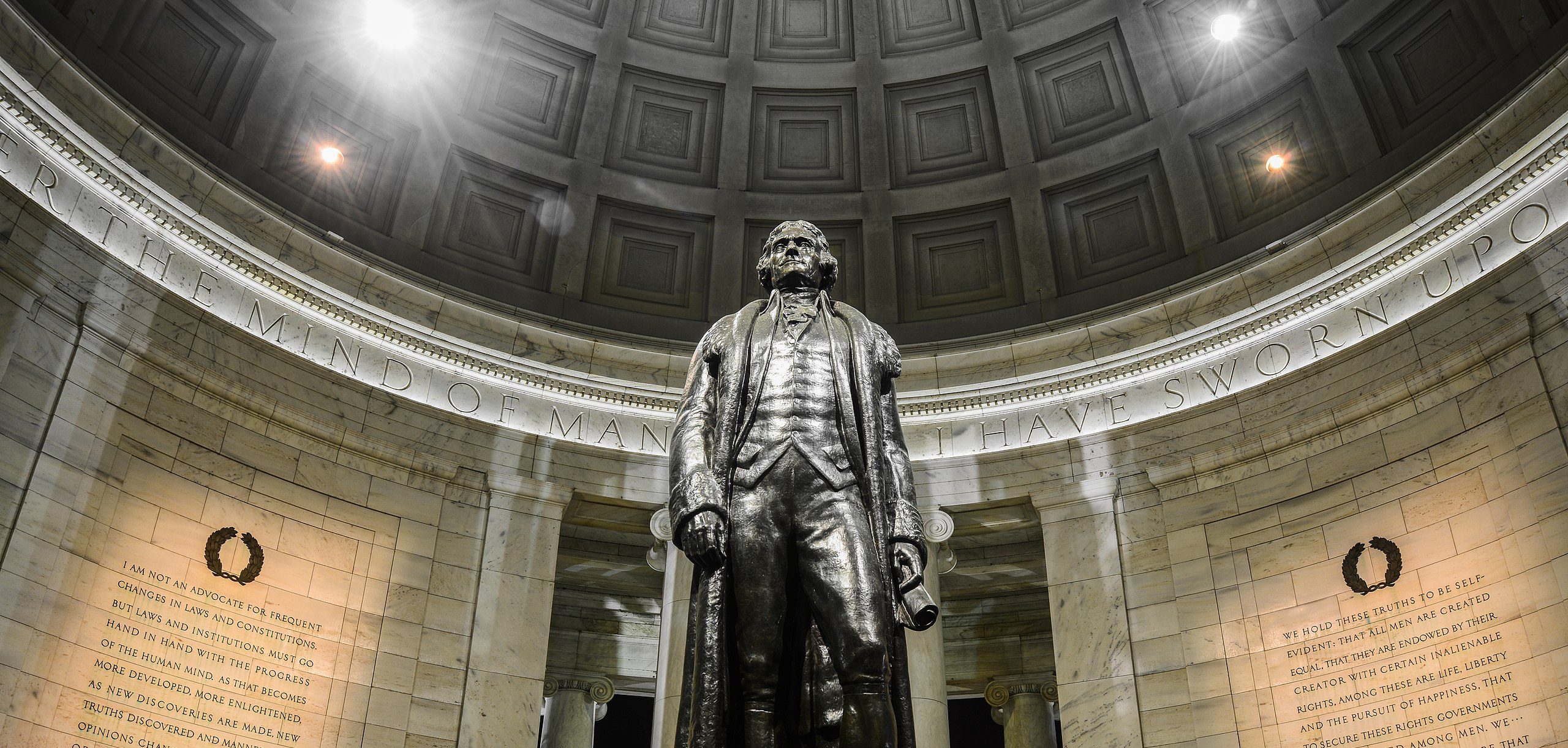

As Jaffa points out in another book, Storm Over the Constitution (1994), when James Madison and Thomas Jefferson became trustees at the University of Virginia, they included Locke’s Second Treatise and Algernon Sidney’s Discourses on Government in the law curriculum as the authoritative sources for “the general principles of liberty and the rights of man.”They then turned to the “best guides” for “the distinctive principles of the government of our State, and of that of the United States,” the first of which was the “Declaration of Independence, as the fundamental act of union of these states.” (It remains today the first of the organic laws of the United States in the U.S. Code.) The nation’s “birthday” was commemorated every July 4, right from the beginning. When the mayor of Washington, D.C., was planning a celebration of the Declaration’s fiftieth anniversary in 1826, he invited the two signers still alive, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, to be the distinguished guests of honor. (Neither was well enough to attend.)

The Federalist Papers explain that legitimate government is instituted when the people “cede to it some of their natural rights,” (Federalist 2), and Federalist 84 opposes the proposal for a Bill of Rights by affirming that “the Constitution is itself, in every rational sense, and to every useful purpose, a Bill of Rights.”

Similar language and arguments appear throughout the founders’ speeches, letters, and other writings before and after the Declaration of Independence. For example:

- Alexander Hamilton, “The Farmer Refuted,” 1775: “The sacred rights of mankind are not to be rummaged for among old parchments or musty records. They are written, as with a sunbeam, in the whole volume of human nature, by the hand of the divinity itself.”

- George Mason, Virginia Declaration of Rights, 1776: “all men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.”

- George Washington, Circular to the States, 1783: “The foundation of our Empire was not laid in the gloomy age of Ignorance and Superstition but at an Epoch when the rights of mankind were better understood and more clearly defined than at any former period.”

- John Quincy Adams, Jubilee of the Constitution, 1839: “The Declaration of independence and the Constitution of the United States, are parts of one consistent whole, founded upon one and the same theory of government . . . expounded in the writings of Locke, but had never before been adopted by a great nation in practice. There are yet, even at this day, many speculative objections to this theory. Even in our own country, there are still philosophers who deny the principles asserted in the Declaration, as self-evident truths—who deny the natural equality and inalienable rights of man—who deny that the people are the only legitimate source of power—who deny that all just powers of government are derived from the consent of the governed. Neither your time, nor perhaps the cheerful nature of this occasion, permit me here to enter upon the examination of this anti-revolutionary theory. . . . ”

The state constitutions adopted during the founding era also echo these principles, using the same Lockean phrases. For example, Virginia’s constitution states “That all men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights,” while Pennsylvania’s is even more explicit: “That all men are born equally free and independent and have certain natural, inherent and inalienable rights, amongst which are, the enjoying and defending life and liberty, acquiring, possessing and protecting property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.”

Only a tendentious misreading of the founding-era documents can deny the overwhelming influence of Lockean natural rights theory.

Though natural rights belong to us as human beings, this does not mean that the founders intended to secure the natural rights of the whole human race. As Jaffa showed, the American people established free government only for themselves, which is as far as their authority extended. Moreover, they doubted that every nation was capable of self-government. The American experiment in liberty was possible only because its citizens possessed the virtues, habits, and opinions necessary for republican liberty.

That brings us to the second objection: that the founding was “liberal” in the modern sense and is therefore the source of today’s subjective “values” and crass self-interest. Here again Jaffa showed that the historical record proves the opposite. The founders were emphatic that only people who were moderate, courageous, and just could exercise self-government. The American experiment in liberty was considered possible because the founders expected—and encouraged—the citizens to remain religiously observant and morally virtuous.

Jaffa’s writings included dozens of long quotations from the historical documents making this point. For the purposes of this article, a few representative examples must suffice:

- Massachusetts Constitution, 1780: “the happiness of a people, and the good order and preservation of civil government, essentially depend upon piety, religion, and morality.”

- Northwest Ordinance, 1787: “Religion, morality, and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.”

- George Washington, First Inaugural Address, 1789: “there is no truth more thoroughly established than that there exists in the economy and course of nature an indissoluble union between virtue and happiness.”

The corruption of the American republic (and that it is now deeply corrupt there can be no doubt) originated not with the political theory of the Declaration but with what Jaffa’s student Charles Kesler has called the “Three Waves of Liberalism.” Virtually everything that is wrong with the United States today can be traced to the rejection of the founders’ natural rights philosophy, by first the progressives in the early 1900s, then FDR’s New Deal, and finally the cultural revolution of the 1960s. Step by step, the left replaced nature with capital-H History as the ground of political authority, made government the source of our rights, and replaced individual equality with egalitarian social engineering and group identities. This quasi-Marxist understanding of capital-P Progress presumes that History is unfolding toward the rational state governed by a highly educated elite. Our bureaucratic ruling class presumes that because it is on the right side of History, it has both the right and duty to rule the uneducated masses without our consent. This, and other self-serving dogmas of our woke tyranny, are the very opposite of what Jefferson so eloquently proclaimed in 1776.

The problem with opposing leftists on the basis of tradition alone is that they simply can, and do, say that this is a tradition of “white hegemony,” which they reject. (See the 1619 Project.) It is much more effective to argue that today’s managerial class rejects the equal protection of the laws and wants to rule us without our consent.

Moreover, progressives have controlled many of our key institutions—including education and the federal bureaucracy—for more than a century. So in some ways modern liberalism has become our tradition. The current Supreme Court has been winning victories for the right lately by rejecting bad precedents. But this only proves that stare decisis, or tradition, must be viewed in light of first principles.

Harry Jaffa argued that the founding was an act of supreme statesmanship and the principles of the American Revolution represented a coherent whole that must be understood and defended in its entirety. If the right wants to rouse the American people to a recovery of our republican liberty, it can do no better than to rally around the self-evident truths of the Declaration of Independence—to which our forefathers pledged their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor.