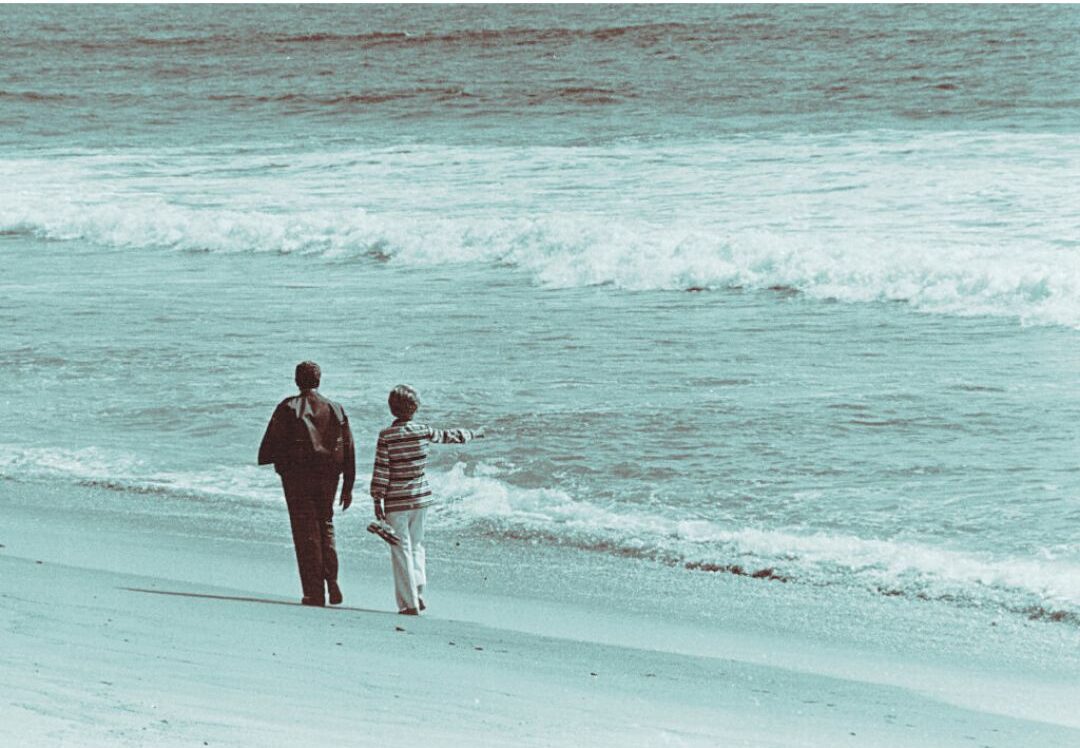

It’s a canonical image of Richard Nixon, weirdo:

Marching on the beach in the most subversive year in American history, 1969, the new president parallels the Southern California surf in wingtips. In a year of cults, communism, and killing celebrities, Richard Milhous Nixon couldn’t be bothered to even check his Johnston & Murphys while enjoying the coast.

Fifty-five years on, the idea of Nixon, the bête noire of the Baby Boomers, as not only a California president but also the first commander-in-chief from the Golden State may seem almost unimaginable to those born after the year 2000, by which time the West Coast had become the Left Coast, home of all that is politically blue.

And yet Nixon’s birthplace—and political base; he won his home state in three presidential elections—was not incidental to who he was but was at the root of his psychology, argues the attorney and Nixon fan Paul Carter in Richard Nixon: California’s Native Son. This richly researched volume is not critical of the man in the slightest—and it leaves the reader not minding.

National cognitive dissonance about the fortieth president has been dealt with before, notably in fiction. “Kennedy? Nouveau riche, a recent immigrant who bought his way into Harvard,” the antihero of Mad Men, Don Draper, says in the Sixties setpiece’s first season.

“Nixon is from nothing,” he continues. “Abe Lincoln of California, a self-made man. Kennedy, I see a silver spoon. Nixon, I see myself.” Commentators would later remark that the sullen, sensual Draper was Kennedy on the outside and Nixon within. (Lincoln, for his part, discussed California on the day he died.)

In Carter’s telling, Nixon’s attraction to a figure like Henry Kissinger was neither random nor an expression of will to power. Much as with Lincoln, what Barry Gewen in the title of his 2020 Kissinger biography called the inevitability of tragedy weighed on Nixon more heavily than it did on his rather close Californian friend Ronald Reagan (Carter emphasizes the warmth of the duo’s relationship).

Perhaps Nixon took it all too seriously.

“There has been a remarkably accidental air about Reagan’s career,” Ron Rosenblatt wrote in his Time Man of the Year profile of Reagan in 1981:

It has always borne the quality of something he could take or leave. The image of the non-politician running for office, antilogical as it is, has had its practical advantages, but it is also authentic. Because Reagan knows who he is, he knows what he wants. . . . In 1976, after an all-out and failed attempt to capture his party’s nomination, he genuinely did not wish to be Gerald Ford’s Vice President. When Ford’s invitation went to Bob Dole, Reagan loyalists were crestfallen, reading in that rebuff the end of their man’s life in politics. Only Reagan took it well, content to settle forever on his ranch, if it came to that.

Nixon, by contrast, was engulfed by political conflict as early as the 1952 campaign, when he served as running mate to the revered General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Allegations of a slush fund maintained by millionaires for his benefit threatened to cut Nixon’s career short before he reached the age of fifty. At the darkest hour, the previous Republican nominee for president, Thomas Dewey, phoned Nixon to drop out, quite plausibly with the tacit approval of Ike.

Nixon recovered with the fabled “Checkers speech.” Carter makes the point that Nixon remains to this day an underrated orator. But, he writes, “nevertheless, the experience left deep scars, and more than twenty years later Nixon admitted that the agony of the fund crisis had stripped the fun and excitement from campaigning.”

Nixon surmounted a tempestuous early life. But as one reads Carter’s work—essentially a linear biography—one can feel its subject’s innocence evaporating. The world broke Nixon and his heart as a child and as an adult.

The overwhelming takeaway from Carter’s work is the astonishing triumph that was the life of Richard Nixon.

A tantalizing side story in Carter’s account is Nixon’s resemblance to Herbert Hoover, his predecessor in more than one respect. Hoover had been the bogeyman Republican president. Hoover had been the young punk with California connections (from his time at Stanford). Hoover had been the one-time Wunderkind who went bust. (President Woodrow Wilson had wanted Hoover to succeed him as a Democrat in 1920.) Hoover had also been the wiseman exile with an affinity for New York—Hoover died in the Waldorf Astoria; Nixon died at New York-Presbyterian.

But this book, and this story, is more SoCal sunshine than midwinter Manhattan moroseness. The overwhelming takeaway from Carter’s work is the astonishing triumph that was the life of Richard Nixon. In a reminder that the past is past, Nixon not only carried California three times (four, if you count his 1950 Senate run) but also went undefeated with the Los Angeles Times editorial board. The images evoked in these pages of the country as it was then can be bittersweet, but they’re essential to understanding how Nixon was Californian to the bone.

“He wanted to be in his home state when the announcement was made,” Carter writes of Nixon’s 1960 presidential campaign kickoff. “California supported Nixon, naming him the grand marshal of the Pasadena Rose Parade on January 1, 1960.” Later: “Nixon was introduced not as a presidential candidate but a ‘Californian . . . a man of whom we are all extremely proud.’”

A cavalcade of classic Southern California spots (though Nixon was cheered in San Francisco, too) are namechecked throughout: the Hollywood Bowl, Dana Point, Long Beach, Pacific Palisades, his native Whittier, any number of Hiltons (Conrad was a close friend), the Century Plaza (his favorite), and on. Nixon was an LA man.

The myth of Nixon the square doesn’t jibe with Nixon the Hispanophile. But that’s apparently what he was. His famed house in San Clemente, La Casa Pacifica, was pure Spanish-California Mission revival. And Nixon, running for president in 1960, spent Election Day drinking margaritas in Tijuana. If nothing else in this volume makes readers nostalgic, the traffic situation that allowed the presidential candidate to navigate that journey with ease in a day will.

“Friends of Abe,” the LA secret society of Republicans, disbanded in the ramp-up to Donald Trump’s original election in 2016. But a striking number of Trump-era heavy hitters have Hollywood connections: Steve Bannon (formerly of Laguna Beach, which he once told me has “bad vibes”), Tucker Carlson of La Jolla, Stephen Miller of Santa Monica. Until recently, though, the air around such Southern California GOP associations was Reaganesque, not Nixonian.

Carter’s work is a necessary corrective as Nixon’s legacy becomes more voguish. As Trump’s appeal endures, the cultural and political power of the Baby Boomers—those inveterate Nixon-haters—is waning.

“Nixon was the first southwestern individualist to be a national candidate,” Carter writes. “Nixon believed in the Jeffersonian Republican principle that ‘the greatest guarantee of freedom is decentralization of power.’” Pitching himself for governor in 1962—a failed endeavor in which Nixon violated a personal rule by seeking a job he didn’t really want—the future president said, “We, the people of California, with a great tradition of seeking opportunity, with a true frontier spirit, cast our vote for free enterprise, self-reliance,” and “local responsibility.”

According to Carter, “Nixon’s greatest love was the ocean,” and his San Clemente neighbor was “John Severson, the laidback founder of Surfing magazine.” The Pacific location—the “Western White House”—wasn’t just idyllic, however. At times it was ideal for statecraft, such as when Kissinger was able to land speedily coming back from China and hasten discussions for the shock opening of relations with Beijing. Nixon also hosted the Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev in California, a career highlight. (Brezhnev’s predecessor, Nikita Khruschev, had pledged to make far eastern Russian port city Vladistok “our San Francisco.”)

Carter divulges that Nixon likely went to the grave having shared a bed only with his beloved wife, Pat (who emerges here as more “Nixon” than Nixon—a political fighter par excellence). Perhaps relatedly, “Nixon’s religious faith was, in his own words, ‘intensely personal and intensely private,’ and to those who knew him, while he did not wear his spiritual beliefs on his sleeve or quote scripture in any political speech, it was clear that Nixon was ‘a deeply religious man.’”

Nixon the tactile politician—man to man, man to woman—was a sight to behold, says Carter. Arguably the greatest handshake politician in American history, Bill Clinton, headlined Nixon’s eulogies in 1994, saying, “Today is a day for his family, his friends, and his nation to remember President Nixon’s life in totality . . . May the day of judging President Nixon on anything less than his entire life and career come to a close.”

(Away from person-to-person interactions, something of Nixon got lost in translation to other media, including, in a cruel irony, those his home state perfected. As reported by Joe McGinniss, when the future Fox News impresario Roger Ailes met Richard Nixon in 1967 on the set of the Mike Douglas Show, Nixon told Ailes, “It’s a shame a man has to use gimmicks like this to get elected.” Ailes replied: “Television is not a gimmick.”)

The left-wing historian Rick Perlstein remarked after completing his book Nixonland that the story of the country Nixon created “isn’t over.” At his sixty-second birthday party on January 9, 1975—five months after resigning from the White House—Nixon told the gathered: “Never dwell on the past. Always look to the future.” He had written in his diary on December 7 of the previous year: “I simply have to pull myself together and start the long journey back.”

Nixon was an unusually introspective man and politician from a setting that lends itself to reflection. As Carter writes of the evening the ex-president first arrived back in California after resigning: “Richard Nixon was now alone at La Casa Pacifica, his presidency having ended with no celebration, no fanfare. That evening he stood on the bluff overlooking the Pacific, watching the waves crash on the beach.”