Ecclesial polemics are nothing new for the Church of Rome. Paul famously resisted Peter “to his face” over controversies in the early Church. Athanasius stood contra mundum when most of church officialdom was in heresy. Jerome was not exactly delicate with his language in his correspondence with Augustine on the interpretation of Scripture. The generally pro-papal Dante placed the reigning pope in hell in his Inferno, and Boccaccio had no problem telling stories about ravenous and oversexed ecclesiastics preying on youths in fourteenth-century Rome. The Archbishop of Paris was locked in what seemed to be mortal combat with the Abbess of the Abbey of Port-Royal-des-Champs in the seventeenth century over the latter’s Jansenism.

Examples could be multiplied in every era and every country over the two-thousand-year history of the Church, and so, its conclusions aside, it was perfectly predictable that the Second Vatican Council (1962–65) would be met with controversy. The pope who called the council, John XXIII, certainly knew that controversy would come, yet his position was that the Church should not be deterred by those whom he called “prophets of doom.” Hence, his opening words to the council were “Gaudet Mater Ecclesia”: “Mother Church rejoices.”

Sixty years later, polemics regarding the council have not calmed down, and in fact they have only increased in the past decade. The general laxity in church discipline, catechesis, and sound liturgy that immediately followed the close of the council and was the hallmark of the 1970s seems—after an interlude—to have re-emerged under the pontificate of Francis. While there may be many flashpoints for this cultural dissolution, not a few critics continue to point to the Second Vatican Council as the event where the Church lost her nerve, forfeited her heritage, and ceased to be Catholic.

A recent response to these criticisms is George Weigel’s To Sanctify the World. Weigel avoids the unthinking optimism of some of the council’s defenders and instead focuses on the original intent of the council as conceived by Pope John XXIII and the cultural crisis that, in the pope’s eyes, made the council necessary. The book does not attempt to dissect the “legislative history” of the council documents, an exercise that preoccupies the Catholic blogger industrial complex in many discussions of Vatican II. Rather, Weigel presents the actual text of the council’s documents—which, in many cases, was ignored or improperly applied after the council, sometimes with disastrous results.

The book is divided into three parts: an analysis and summary of the state of the Church and the world before the council, a précis of the council’s documents, and a brief consideration of the pontificates of the post–Vatican II popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI as keys to understanding the council.

The first part, “Why Vatican II Was Necessary,” provides a useful account of the intellectual, political, and cultural currents of the roughly ninety years prior to 1962. By the end of Pius IX’s reign in 1878, the world had changed dramatically. The dominant philosophical and political thought of the nineteenth century had sought to build a world based upon human reason alone. While the temptation to act as if God did not exist was as old as man, the popularity of secularism, individualism, rationalism, and materialism grew in the mid- to late 1800s, spurred by influential schools of philosophy, political movements and revolutions in Europe, the industrial revolution, and a turn toward spiritualism as opposed to a divinely revealed religion. John Henry Newman, reflecting on challenges to the Church, commented in 1873: “Christianity has never yet had experience of a world simply irreligious.”

And this loss of the sense of the supernatural was spreading not just outside the Church but also within it. Eighty-five years later, a young professor named Joseph Ratzinger presciently warned of the “new paganism . . . growing steadily in the heart of the Church.” He noted the loss of supernatural faith among his co-religionists and the reduction of the sacramental and devotional life of the Church to a mere cultural exercise.

As these dark clouds were gathering, however, new light was dawning with a reappreciation among some Church leaders and theologians of the wisdom of the Church Fathers of the first five centuries A.D. These early Church Fathers—the immediate generations after the Apostles—dealt with a world that, while not “irreligious” per se, had never known the message of Christ. Perhaps the Fathers of the Church had something to say to the new pagans.

Weigel’s clear synthesis of the situation prior to the council is a powerful testimony of the wisdom of lodestars such as Newman and Ratzinger who, along with John XXIII, were convinced of the need of the Church to engage the world in a new way. As the pope described the purpose of the council: “at issue is the response of the whole world to the testament of the Lord which he left us when he said, ‘Go, teach all the nations . . . ’. The purpose of the Council is, therefore, evangelization.” And he added in his opening address to the council: “The greatest concern of the Ecumenical Council is this: that the sacred deposit of Christian doctrine should be guarded and taught more efficaciously.”

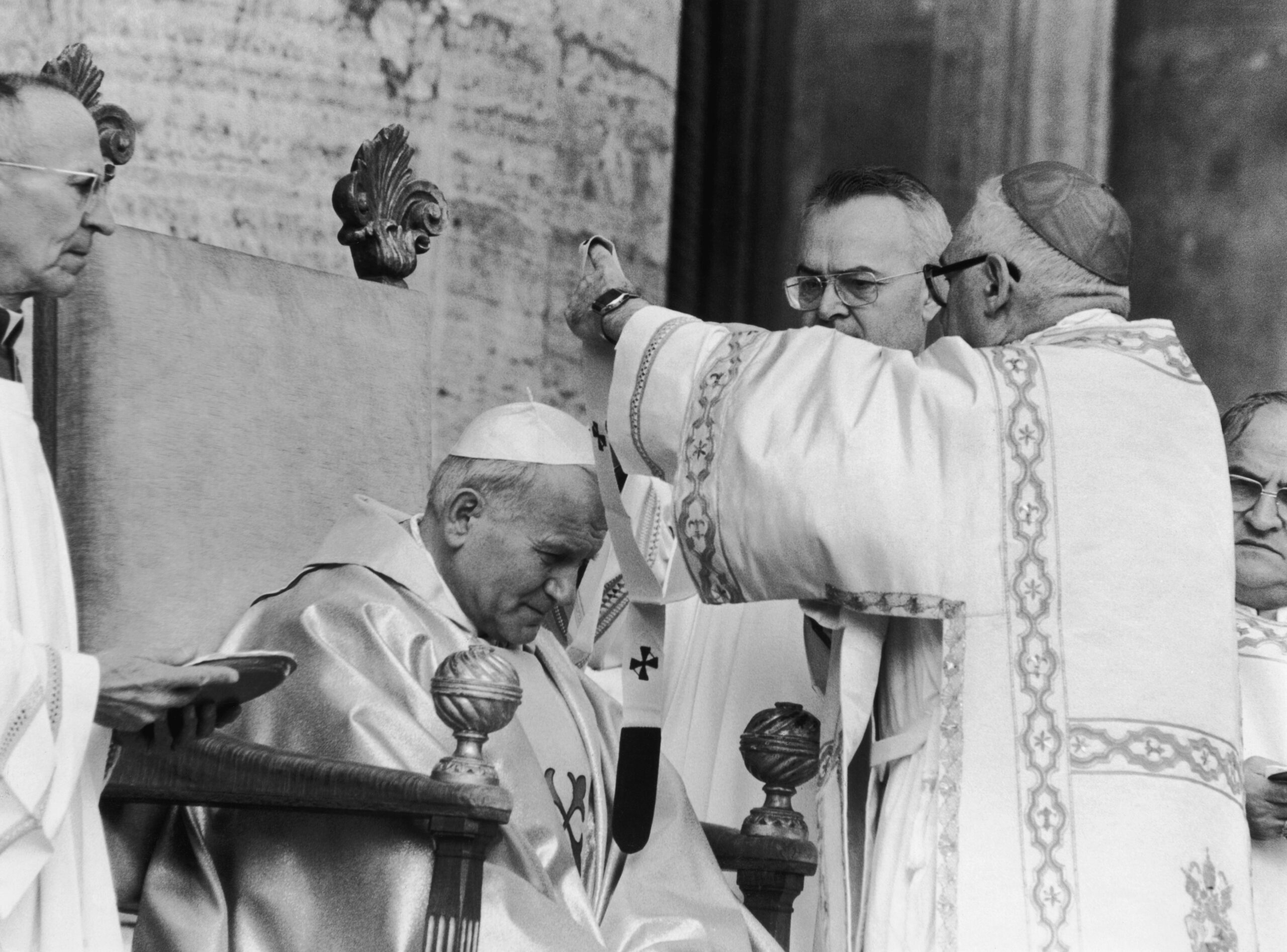

But the council’s implementation in the lives of Catholics tells a different story. To be sure, its results were a mixed bag, largely dependent upon individual pastors of the Church. In Western Europe and North America, the Church’s absolute retreat from authentic Catholic worship and devotions, the systemic emptying and explaining away of the miraculous as the products of primitive and non-enlightened ages, the complication and confusion engendered by academics of simple revealed truths once held by all, and the continuing lack of discipline and recourse to supernatural means by the pastors of the Church—all in the name of the “spirit of Vatican II”—have come to be seen as inseparable from the council itself. Yet there are examples of a more serene implementation of the council. Cardinal Karol Wojtyla’s Archdiocese of Krakow was one of them. Wojtyla’s Sources of Renewal, originally published in 1972, is a deep dive into the documents and teaching of Vatican II and its implementation at the diocesan level. Paradoxically, it was officially irreligious Poland that produced many of the council’s desired evangelistic fruits, led by the man who would become Pope John Paul II.

The second part of the book presents what the council’s documents actually said. Weigel explains the different types of documents issued by the Council Fathers and describes how to read these teachings in light of Church tradition, including previous ecumenical councils and papal teaching. In this section, Weigel is particularly clinical in simply stating what the documents say, mostly avoiding analysis of the language employed, which, in some instances, may admit of unorthodox interpretations. It would have been helpful if he pointed out some of the more controversial passages and indicated how these could be exploited by unscrupulous churchmen. Perhaps, though, Weigel sees himself as writing for a new generation of readers with varying levels of historical and theological knowledge and so wants to avoid pedantry. Many other books on the council and even contemporary reports of the time speak about candid theological discussions, points of emphasis between “conservative” and “liberal” prelates, certain actions on the council floor that “prove” the council was rigged in a way that departs from Catholic tradition. Weigel, in contrast, insists that the documents and teachings themselves are in continuity with the faith of the Church.

But, whether Weigel acknowledges it or not, there were ominous signs that Vatican II wouldn’t be received as intended, largely due to bishops who might have been tagged by a young Ratzinger as “pagans in the Church.” The cultural revolution of the 1960s, an emerging “magisterium of theologians,” the ubiquity of Western media and media-savvy priests such as “Xavier Rynne,” who wrote weekly dispatches for the New Yorker during the council, and—most importantly—the loss of what John Paul II later called the “sense of God” all served to validate the predictions of Newman and Ratzinger. Even in the best-case scenario, the council could never have counteracted these cultural forces.

A strange irony was at work in the 1960s: in the decade that proclaimed freedom and the breaking of fetters from all authority, people bound themselves more tightly to so-called “experts,” including in following influential but not always trustworthy leaders in the interpretation and implementation of the council. The voice of Rynne, a gossipy priest with advanced degrees whose worldview was more closely aligned with Manhattan’s Upper East Side, was heard over that of Wojtyla, a pastor behind the Iron Curtain who had decades of pastoral experience with the real issues of family life and struggle with faith. Likewise, the media with its penchant for novelty and its power to impress images upon minds chose progressivist bishops such as Auxiliary Bishop James Shannon (who later left the Church and married a thrice-divorced woman) to chart the course for the “new Church” and portrayed others such as the council peritus and experienced parish pastor Monsignor Rudolph Bandas as backwards and authoritarian, especially on issues of liturgy, traditional moral teaching, and ecclesial discipline.

Yet amidst this confusion and turmoil, the pontificates of John Paul II and Benedict XVI served as a corrective from 1978 to 2013. In the third and final section of his book, Weigel says these pontificates are the keys to the council and runs through their major themes, which in his view provide the articulation and correct reading of Vatican II. These popes’ great strength was reiterating the basic teachings of the Church in a time of rapid change. John Paul II’s most significant contribution was to reaffirm the truth that man can only understand himself, his dignity, and his ultimate end through Christ. This was seen most clearly in John Paul II’s magisterium, especially his restatement of Catholic doctrine in the publication of the Catechism of the Catholic Church; possibly the greatest of his encyclicals, Veritatis splendor, reasserting Catholic moral teaching; and the declaration Dominus Iesus (authored by then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger), reasserting the Church’s traditional teaching that Jesus Christ is the only way that any human person can be saved. Continuing the work of the council and the program of his immediate predecessor, the former council peritus Joseph Ratzinger/Pope Benedict XVI brought dignity back to Catholic worship, and his pontificate checked some of the excesses of the post-conciliar liturgical experimentation. His Summorum pontificum stands for the proposition that “what was holy for previous generations is still holy for us today,” and, far from rejecting Vatican II, it has gone a long way to fulfill the dictates of the council’s document on the liturgy, Sacrosanctum concilium.

Yet observers are right to read Weigel with a raised eyebrow, given his past reckless political alignments and his sometimes haughty analyses of ecclesial affairs. He has served as a willing envoy of the Washington establishment to persuade popes to take a favorable position on U.S. foreign policy (especially regarding the Iraq War), and this causes one to question whether some of his conclusions are affected by his prudential preferences in politics. Likewise, his past analysis of Benedict XVI’s encyclical Caritas in veritate, in which he delineates and defends those portions of the encyclical which he claims are Benedict’s (the pro-life, pro–free market, anti–world government parts) and which are from a Vatican committee (the wealth redistribution and world government ones), demonstrates a lack of docility when one is faced with ideas that may conflict with his previous policy positions.

Analysis of interior acts is a near impossible task, but one can judge external acts as well as their consistency with the teaching of Christ as articulated through the ages. Regardless of its rightful recognition of the need for “evangelization,” Vatican II has been put into practice in ways that have caused great confusion and harm. The mendacity of the clergy, a preoccupation with this world instead of the salus animarum (“salvation of souls”), and the enforcing capos of Roman officialdom who cynically contradict the plain words of the council documents and the Church’s Catechism while claiming fidelity to them all have played into the hands of principalities and powers who have as their aim the erasure of the name of Jesus and the damnatio animarum (“damnation of souls”). The “spirit of Vatican II” is indeed a spirit that must be exorcised.

That said, a proper understanding of the council is greatly needed among a new generation of Catholics, and Weigel’s book is a step in that direction. To Sanctify the World is not the final word on the council, but it can serve as a primer for Catholics who have not read the conciliar documents or are unfamiliar with the context in which the council was convoked. And it can help to correct what is possibly the chief ecclesial error of the post-conciliar age: the opinion that a new Church was formed at the council, as is claimed by practitioners of the “synodal way,” along with the adherents of the traditionalist Society of Saint Pius X. One acknowledges throughout history the presence of the Judases who wish the Church to be something it is not, and indeed they must be resisted. But to think that the council replaced Christ’s Church with one of its own making is to believe that Christ has abandoned his bride or that he would contradict himself. Those who hold this position (both of the radical traditionalist variety and the liberal materialist variety) will inevitably, in both cases, seek this-worldly solutions to their intellectual and spiritual predicament. Both are untenable positions for a Catholic. Christ, after all, has said he will be with his Church always, even to the end of the age.