The MetLife Building straddles Park Avenue at Forty-Fifth Street. Its massive ugliness looms over the Helmsley Building in front of it and Grand Central Station behind. Commuters fast marching down Park Avenue to catch Metro-North will take the walkway through the Helmsley Building, dodge cabs on Forty-Fifth Street, enter the lobby of the MetLife Building, hurry past expense-account restaurants, push through revolving doors, and ride short escalators down to the magnificent main hall of Grand Central Station.

In the olden days, back when the MetLife Building was the Pan Am building, back when they landed helicopters on the roof—that is, until one tipped over fifty-nine floors up and killed a bunch of people—back then, right before the revolving doors and the escalators, the commuter might pause at the newsstand, a huge one, with row upon row of magazines, a banquet for magazine readers and browsers. Print ruled, and magazines were king.

Fashion magazines, architectural magazines, sports magazines, newsweeklies, political magazines, hunting and fishing magazines, thought leaders, city magazines, women’s magazines collectively called the Seven Sisters, business magazines—dozens of categories, hundreds of titles, all fat with national ads. Wine, liquor, domestic cars, imported cars, banks, men’s and women’s fashion, watches, books, destination travel, airlines. They all wanted to reach the magazine reader because he was legion, had money, and spent it.

Ambitious ad sales guys had a magazine idea tucked up in their briefcases; start it up, sell it for ten times multiples, and make a bundle. Some did get rich. There was an investment bank—Veronis and Suhler—founded solely to manage the sale of magazine properties. Veronis and Suhler doesn’t do that any longer; the newsstand at MetLife isn’t there any longer. Hardly anyone noticed, but there was a new thing, a revolutionary ad company called DoubleClick, hovering like a bird of prey, with algorithms like claws, waiting to devour the flesh and powder the bones of magazines.

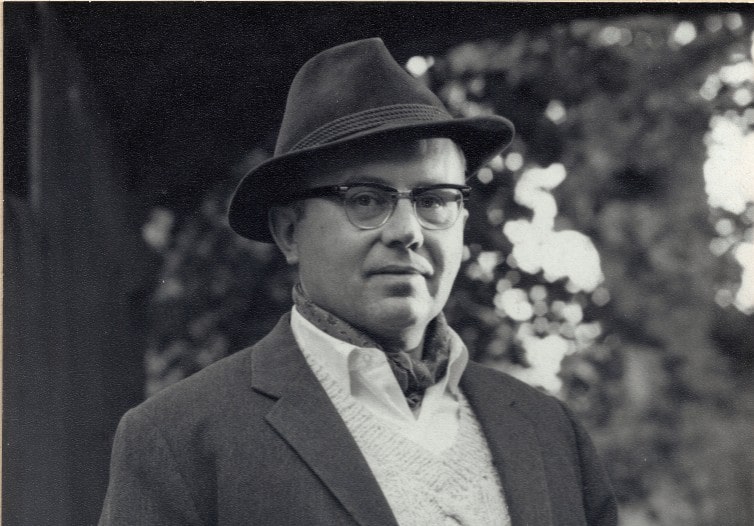

Lance Morrow stood atop that magazine world for a good long while. He was back-page essayist for Time, which was arguably the most influential magazine for much of the twentieth century. Consider magazines as real estate. Time was the most valuable journalistic real estate in the country, perhaps the world. Morrow occupied the most valuable part of that property for twenty-nine years. It was a spot created for him by the Time editor Henry Grunwald.

Readers tend to pick up a magazine, look at the cover, flip to the table of contents, and almost immediately turn to the back of the book, especially the back page. They know something special resides there. Advertisers know that, too. Advertisers pay a premium for spaces inside the front cover, on the back cover, and inside the back cover. That Morrow had a column inside the back cover for so long meant presidents, senators, governors, corporate chiefs, small-town bankers, and mom and pop read his column. Nothing remotely similar to that magazine and that column exists today. Yet besides the final column, Morrow wrote much more: cover stories, hundreds of them, and more “Man of the Year” pieces than any other writer at the magazine.

One has to choose when reading the millions of words Morrow has published. I picked his life instead of his columns. At the relatively young age of forty-five, he produced the first of three memoirs. He is slightly embarrassed by that but explains it by invoking Montaigne, who wrote about the minutiae of his life at a similar age. In the opening pages of The Chief (1984), a significant theme emerges: Morrow’s fraught relationship with his father. The Chief—which is really about life with father and, to a lesser extent, life with mother—opens in the restaurant on top of Rockefeller Center, where Morrow and his father can hardly look at each other. They fiddle with silverware and uncomfortably talk about politics. Morrow says politics was their only safe zone.

Morrow and his brother were feral boys. They often lived like Tom and Huck. Boys in those days were allowed to be boys—that is, allowed to be “savages.” All boys were raised ferally until recent helicopter days. But it is astonishing how ferally Lance and his brother were raised. In the summer of 1949, his father dropped ten-year-old Lance and his slightly older brother Hughie at the end of a dusty road at a broken-down cottage near Charles Creek on the Chesapeake Bay in southern Maryland. The ruined cottage had no electricity, no running water, no toilet. They had to get their own blocks of ice to keep their hotdogs in an outdoor ice chest. The food tended to spoil as the ice melted by the end of the week. The only near-adult with them was nineteen-year-old Aunt Sally, who laid on the grass in her bra by the empty, weed-infested pool while the boys Huck Finned for miles around with the local black kids.

They were dropped in this lonely place because, Morrow says, his mother “wanted us gone. She told my father she could not cope with us, with her life, with everything.” Mom and Dad were barreling acrimoniously toward divorce.

We see young Lance sitting in a tree at the end of the week, waiting for hours, straining to see his father arrive from Washington, D.C., bringing hotdogs, Ritz crackers, mayonnaise, and milk. His visits sometimes lasted mere moments before he would abruptly leave, the boys looking once more up the road as the dust from the retreating car settled. And then the silence. His father was always leaving. This fatherly remoteness and absence instilled an anger in Morrow, an anger that is a leitmotif though all his autobiographical work. This anger may have been nurtured, but it was certainly inherited. He came from anger and fights. He says the past in his family may have been something like a midnight riot in a graveyard: “The past was full of grievances. It lashed out, sometimes in the dark. The past was insane.”

Two years later, when Morrow was twelve, his father landed him a job as a Senate page, that extraordinary institution of boys running errands for the grandees of American politics, later ruined by sex scandals and technology. His boss was Lyndon Johnson’s wunderkind aide Bobby Baker, then only twenty-five. What a time—the end of an epoch when the southerners still wore string ties and senators staged authentic late-night filibusters, after which Morrow might ride the trolley through empty Washington streets back home toward Rock Creek Park. He fetched ice cream for Lyndon Johnson! He watched as the burgeoning political star John Kennedy hobbled into the Senate chamber on crutches. Even committee chairmen turned to watch. Morrow later wrote a book about Johnson, Kennedy, and Nixon in their pivotal political year of 1948.

When Morrow was sixteen, his father dropped him off in the tiny town of Danville, Pennsylvania, where he worked as a reporter for the town newspaper. He put on a phone headset and called the local constabularies, asking what happened overnight. He lived in a rooming house and looked, perhaps enviously, at the rich kids across the river in Riverside. It speaks volumes about the seismic shifts in our country that Riverside, once the country club side of town, now seems tumbledown, boarded up, opioid-plagued. In those days, Morrow preferred the company of the blue collars of Danville. He nipped from a flask of whiskey with a coal miner as they rode a bus through the mountainous night on his way back from a weekend in Washington, D.C. It is hard to imagine such a scene happening today. Somebody would call the cops.

Morrow went on to Gonzaga High School, where he met real Jesuits—tough Jesuits who would send inattentive boys to sit on the fire escape, even in snow. They’d hit you on the back of the head with a book. At Gonzaga, under the influence of his recently converted mother, Morrow joined the Catholic Church. Not long later, he left it (though he returned in later years). As a kind of stick in the eye to the Jesuits, Morrow went scandalously off to Harvard rather than Holy Cross.

All along, Morrow felt like an outsider, which is odd since he was born of Washington insiders and lived up close with so many remarkable men and events, the players of which he knew. His father often lent his car to Martin Luther King, Jr., when King was in town. In a Wall Street Journal article last summer, Morrow described a touch football game in Georgetown with the Kennedys when Ethel was pregnant with Bobby, Jr. She dropped a pass, and Bobby cussed her out. This would have been in the fall of 1953. John would have been newly elected to the Senate from Massachusetts. Bobby had left Joseph McCarthy’s commie-hunting committee and was momentarily adrift. This was history struggling to be born, right before Morrow’s eyes. You do not get more inside than lending a car to Martin or playing touch football with Bobby.

Out of Harvard, he joined the night staff of the Evening Star, the afternoon paper in Washington, D.C. Carl Bernstein bummed cigarettes from him. In the next decade, Bernstein would let Morrow read All the President’s Men in galleys. Morrow was among the first on the scene of the 1964 murder of Mary Pinchot Meyer along the towpath of the canal in Georgetown, where Morrow had played as a feral child. She was the ex-wife of a CIA covert-action chief. She was also one of John Kennedy’s girlfriends and sister-in-law to the Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee. Her murder was a focus of early conspiracy theories in Washington, D.C., which still had a small-town feel in those days.

All of this happened before Morrow went to Time. He modestly says, “I have done nothing memorable in my life, and yet all around me, things have happened.” He has been an observer, a gatherer of facts, someone who explains what he sees and hears rather than an actor on the stage of public events. He is Lazarus, come from the dead, come back to tell you all. And to tell you what it was all about.

He wrestles with these themes in his third and likely final memoir, The Noise of Typewriters, which came out last year when Morrow was eighty-three. Writing a book at that age is all the more remarkable because his “jalopy of a heart” by then had attacked him three times, first while covering the 1976 Republican National Convention in Kansas City when he was a mere thirty-six years old: “A crushing pain in the center of my chest, and a piece of my heart died, in an area the size of a fifty-cent piece.” The second came when he was fifty in 1989, and he wrote an entire book—Heart: A Memoir, 1995—about it. The book has a backdrop of death: his father’s, the slaughter in Sarajevo, and deaths in other places he was reporting from in those days. The third heart attack struck in the spring of last year, just as he was promoting the book.

It is not surprising that Morrow thinks about death a lot. When your heart attacks you, death lingers nearby—you can practically see it. And he writes about it beautifully:

There is a faint sliver moon with a blurring of snow nimbus. The animals are burrowed deep. The night air is just the medium, thin and ruthless, to transmit inaudible, high-frequency shiverings and keenings. They transmit along tight shining wires: numb, helpless and waiting, a vibration of void, the nearest thing in the world has, this time of dead winter (sunless, sapless, the world made of gray deadwood and iron) to death itself.

Typewriters is a meditation on a journalistic world that is now sadly faded. It is a book by a man at the height of his powers, so abundantly confident that much of it is spare, whittled down, decorated like a Japanese home: a bare table, a vase, a flower, a lamp placed perfectly over there in the corner, a chair, no rug, the floor bare. I mention things Japanese because Morrow seems sincerely interested in Japanese culture. It comes up repeatedly in the book, maybe without him even noticing. Perhaps its peace, its quiet and simplicity, assuages his inherited and nurtured anger.

He produces several chapters of only a few hundred words: slightly more than six hundred words on the war correspondent Dexter Filkins, who tells a spare story about a firefight in Fallujah, where American soldiers turn up the volume on AC/DC’s “Hells Bells” and blast away at a building until it grows quiet; reporting and writing lessons from the opening of Hemingway’s Farewell to Arms in less than eight hundred words; a three-hundred-word meditation on writing in which the Harvard biologist Louis Agassiz says, “Look at your fish. Look at your fish”—for days, look at your fish; finally, you will see the fish. Morrow concludes: “Never be certain there is no meaning. Never be certain about anything too quickly. All journalism implies a concealed metaphysics—even a theology: All truth is part of the whole. All is in motion. Be tolerant of chaos. Be patient. Wait for stillness. This is Journalism 101, according to me.” And very Japanese.

Like wrestling with his father in The Chief, in Typewriters Morrow wrestles with another father figure, though one even more distant, indeed one he never met: Henry Luce, the great genius of American magazines and herald of the American Century, the man born in China of evangelical missionaries who envisioned a particular America and gave it back to the readers of his various magazines—first Time, then Fortune, Life, and many others, the best, most important magazines of their many decades. As Morrow says, “mass circulation magazines (especially Luce’s) joined American politics and American religion and American movies in the restless project of making and remaking—or, eventually, unmaking—the national myth.”

Smart-alecky kids in New York journalism smirked at Luce. Even his later editors looked askance at him. He asked for ketchup in even the fanciest restaurants. Though he had attended Hotchkiss and Yale, they thought he was a vulgar rube. As Morrow points out, Luce’s love for small-town America had started to drift out of fashion a few decades before, with writers such as H. L. Mencken and Sinclair Lewis. As they caromed from small towns and farms to Harvard and Yale and then piled out onto the streets of Manhattan, a generation of polished rubes felt free to go after the small-town life they left behind. The readership of Time was coast to coast, border to border, and in every small town across the country, but it was the era when small-town life came in for scrutiny, mirth, rebuke.

Morrow does not care for the 1960s or the Baby Boomers, not the least for their assault on authority. Knowledge that was once passed from father to son now passed from cool uncle to nephew, from older brother to younger brother, from kid to kid, like a joint at the Fillmore East. This was one of the reasons Luce fell into such disfavor. He was too much dad, too much granddad. It did not help that he was monomaniacal for the lost cause of Chiang Kai-shek and a cheerleader for the war in Vietnam.

The other great topic Morrow explores is his trade—for this he presents portraits of certain writers who are now ghosts. Have you ever heard of Otto Friedrich, a journalist Morrow devotes a worthwhile chapter to remembering? Morrow also recalls those who have not yet been forgotten, among them John Hersey, who visited Hiroshima and wrote, in Morrow’s view, the greatest book of journalism ever written: “The youthful Hersey undertook to grasp the event by the means of the simplest, most straightforward journalism. He went to Hiroshima and interviewed people for six weeks and came home and wrote it up in transparent prose: not an ounce of fat or rhetoric.”

Typewriters is a beautiful book about Morrow’s decades spent observing at the top of the world. It is a glimpse of the final fading of the world of print journalism. Time Inc. in those days was catered lunches in wood-paneled offices high above Sixth Avenue, a few blocks from Central Park. There was a shoeshine guy walking the halls, ducking into offices, offering his services—Morrow remembers his name was Jimmy. Ad guys took the company plane to Saratoga for the opening of the races. Memberships at Baltusrol or Winged Foot. Lunches at Lutèce, Le Côte Basque, the Pool Room at the Four Seasons. Black cars lined up on the side streets at the end of the day waiting to whisk Time Inc. paladins wherever they wanted to go.

That world is gone. No more typewriters—that clackety-clack replaced by the less satisfying clickety-click. No more cigarette smoke, scotches at lunch, balls of crumpled paper lying on the floor near the wastebasket. No more real influence.

Morrow says the glory days of magazines ended when Time Inc. stopped printing Life in 1972. There was a passing of the old guard that lived through the Great Depression and World War II—those who lived with fear in the air, always hovering nearby. The new guard were the Baby Boomers, who had not lived with the kind of fear that brings wisdom and maturity of judgment.

Morrow attended the event that may have been the last wheeze of that world: Time’s seventy-fifth anniversary dinner at Radio City Music Hall in 1998. Long lines of limousines disgorged hundreds of the literati, glitterati, and the otherwise notorious: “The stars of the evening were several generations of actors, politicians, baseball players, boxers, industrialists, scientists, ballet dancers, and assorted geniuses, along with the president of the United States, Bill Clinton, and his wife.” Muhammad Ali, Bill Gates, Elie Wiesel, Joe DiMaggio, Henry Kissinger, Mickey Rooney, Lee Iacocca, even Louis Farrakhan and Dr. Death (Jack Kevorkian). Hitler’s documentarian Leni Riefenstahl, too. Everyone was there. “That night felt like the end of something,” Morrow writes. And he’s right. There’s no way the Time of today could repeat such an event.

In 1998, DoubleClick, that bird of prey hovering just off stage, had been scratching around for three years. DoubleClick created the online advertising marketplace. DoubleClick, now owned by Google, captured larger and larger portions of advertising budgets. These days it takes up almost all of them. The money came right out of the flesh and bones of magazines. The current incarnation of Time has only sixty-four pages. It is a pamphlet. A wealthy software salesman now owns it. Sports Illustrated bounced from owner to owner and is now owned by a brand management company and faces an uncertain future. Life was revived, sort of, and is now produced by a digital media company. These are not giants of journalism. These are no longer the most expensive journalistic real estate in the world.

These puny things result from someone like Robert Moses leveling entire neighborhoods to build superhighways, in this case, the internet superhighway that, with a few exceptions, swept all before it. One of the exceptions has been the Wall Street Journal, where you can still read Lance Morrow doing some of the best work in his long and storied career. After nearly sixty years, Morrow still occupies the country’s most expensive journalistic real estate.