Armstrong and Armstrong Rides Again!

By H. W. Crocker III

(Regnery Fiction, 2018 and 2021)

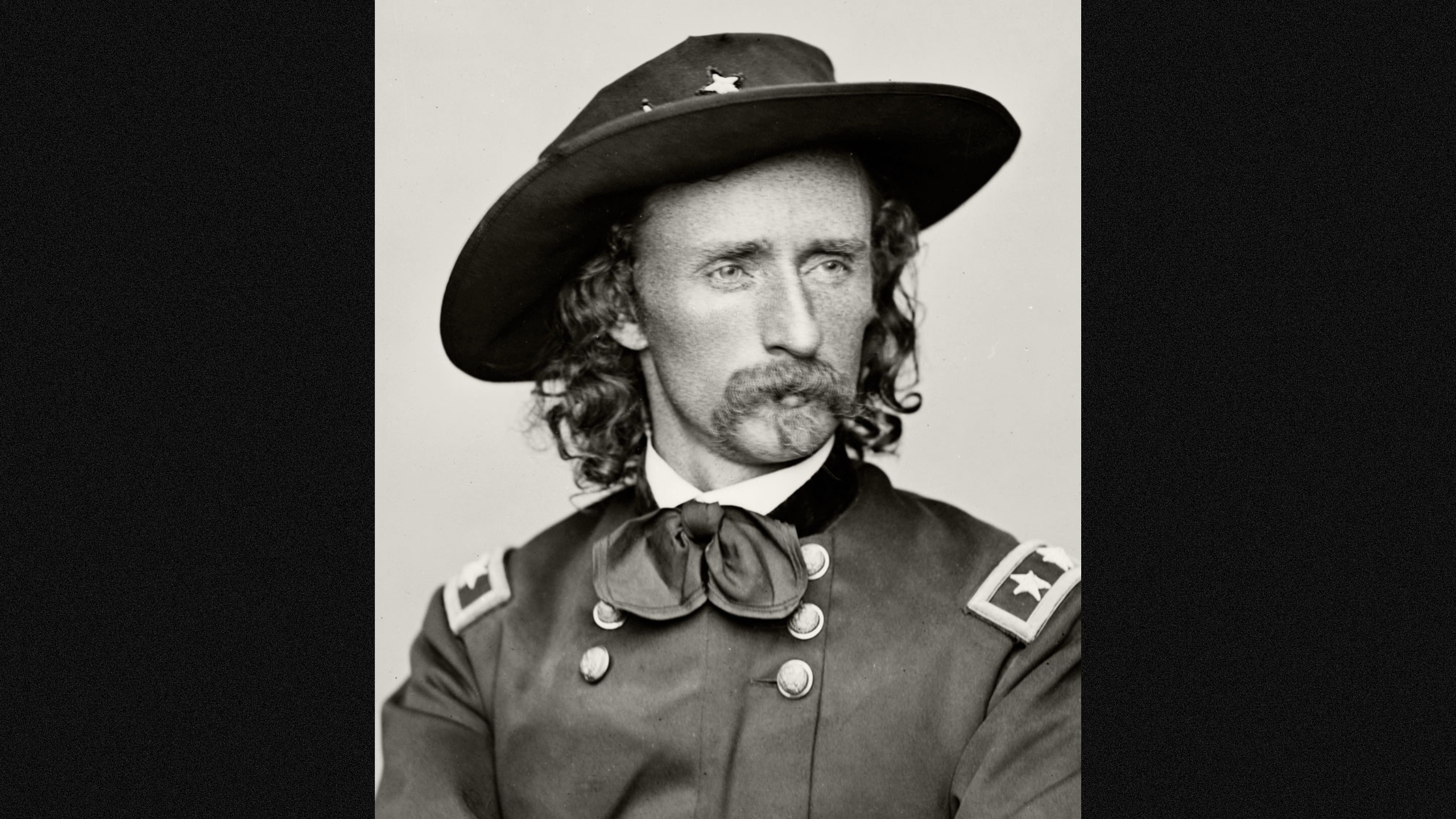

The left’s absurdities are new each morning, and to remain a “decent human being,” you must accept all of them uncritically. There’s only one defense against such cry-bullies: learn to laugh at them—perhaps not in their faces, but at least among ourselves. This tactic is on full display in H. W. Crocker’s Custer of the West series, in which George Armstrong Custer survives the Battle of Little Big Horn and embarks on quixotic adventures.

The first of these, Armstrong, opens with Custer being rescued from the slaughter at Little Big Horn by a white Sioux captive named Rachel, who informs him that the Sioux have faked his death by placing his uniform on the mutilated corpse of a cavalryman. Together she and Custer escape and light out for the nearest frontier town, where he adopts the name that gives the novel its title. On the run from the law after a bar fight turns deadly, “Armstrong” takes up with a traveling can-can show, accumulates an impressive harem of damsels in distress (without betraying his beloved wife, of course), and liberates the town of Bloody Gulch from the clutches of a crooked trading company.

Along the way, he meets seductive traveling-show proprietress Sallie St. Jean, Confederate veteran cardsharp Beauregard Gillette, Indian cavalry scout Billy Jack Crow, and Bad Boy, a dog able to understand the pidgin German that Custer believes to be the universal language of canines. The entire thing is a delightful romp that shifts seamlessly between thrilling Western and outlandish farce.

The second book, Armstrong Rides Again!, finds the eponymous pseudonymous hero still gallivanting across the West. He crosses paths with a Latina beauty who convinces him to travel to the island nation of Nuestraguano and enlist as a soldier of fortune alongside Devil’s Dictionary author Ambrose Bierce. Both become generalissimos in the service of El Caudillo—the island’s Trumpian monarch—and spend the rest of the novel fighting anarchist rebels and measuring swagger sticks. This time around Crocker scales back the slapstick, trading cannons loaded with Chinese acrobats for deadpan dialogue like this: “Assassins tried to kill you last night.” … “Did you interrogate them?” “Can’t—they’re dead.” “That doesn’t help us.” “Doesn’t hurt us much either.”

The politics of Nuestraguano provide more than enough absurdity. This second novel, far more than the first, reaches for a ripped-from-the-headlines relevance to contemporary politics, with mixed success. I laughed when Custer called Bad Boy a “loyal dog-faced pony soldier” but cringed at underdeveloped references to Nuestraguanians being forced to wear flour sacks over their heads as protection against plague. Other political parallels, such as the island’s elite eagerly betraying the national interest for unfettered immigration and free trade and throwing themselves into histrionic fits of false outrage over El Caudillo’s every utterance, were more deftly integrated.

I was ambivalent about the character of El Caudillo. Characters based—flatteringly or otherwise—on our former president are tired by this point, and Crocker is continually nudging the reader’s ribs, whispering, “See? He doesn’t drink alcohol; he has ‘luxuriant golden hair’; he wants to open a hotel.” Crocker does, however, do an admirable job of replicating Trump’s cadences: “I want a country where the women are smaller than the men, don’t you?”

These novels, which contain a rich variety of female characters, are not sexist, though as one reviewer pointed out, “the men are men [and] the women are definitely women.” Sallie St. Jean’s showgirls, who in a revisionist Western would fall somewhere on the continuum between liberated and lesbian, long to leave show business and settle down with husbands. Indeed, a key part of Custer’s quest is finding some for them. I suppose that’s not very progressive.

When it comes to race, however, Crocker makes no attempt to conceal his pro-Confederate bias. In Armstrong, Beauregard laments the loss of the genteel Old South, and Custer doesn’t correct him. “I believed then, and I believe now,” Custer says, “that the South should be treated generously, decently, leniently.” It’s an accurate reflection of the historical Custer’s opinions, which Crocker unfortunately shares. The only full-throated condemnations of the Southern slave economy to be found in the novel come from the mouth of its villain.

Crocker does pay his minority characters the compliment of not reducing them to mere victim status. Billy Jack Crow is permitted to be a Roman Catholic, a lover of European languages, and an ally of the U.S. Cavalry without any of the condescension to which freethinking members of minority groups are so often subjected today. In fact, it is Billy Jack whose wisdom helps Custer integrate his conflicting duties in the midst of his complex double—sometimes triple—life. And nobody worries more about duty than Generalissimo Armstrong Armstrong.

Custer’s macho militarism is a joke, but not a mean-spirited one. Another author’s Custer would exist to deflate the concept of masculine heroism. Crocker’s Custer exists to uphold it. More self-aware characters like Sallie or Beauregard frequently poke fun at Custer, but they’d still follow him into hell. And, at least for the story’s duration, I’d do the same.

Grayson Quay is weekend editor at The Week and a columnist at the Spectator.