The precipitous decline of religious practice by Americans over the last decade has raised questions about religion’s relevance to conservatism in general and to Republican politics in particular. The former National Review staff writer Nate Hochman and the founder of American Compass Oren Cass have argued not only that current culture war skirmishes over race, gender, and parental rights are being contested as secular instead of religious conflicts but also that a new social conservatism that is Trumpian and secular is succeeding where the old religious conservatism failed. The triumph of the LGBTQ movement and the consequent retreat of religious conservatives under the defensive banner of religious freedom plainly illustrate this failure.

For Hochman, religious conservatives have lost the ability to lead the movement; for Cass, religious arguments are not persuasive to American elites. Both seek a new conservative consensus, separate from any religious sanction, from which the movement can turn in a new direction. The 2024 GOP platform chartered a new course by removing or softening language articulating positions on protecting human life, marriage, and family, the top issues of religiously conservative voters.

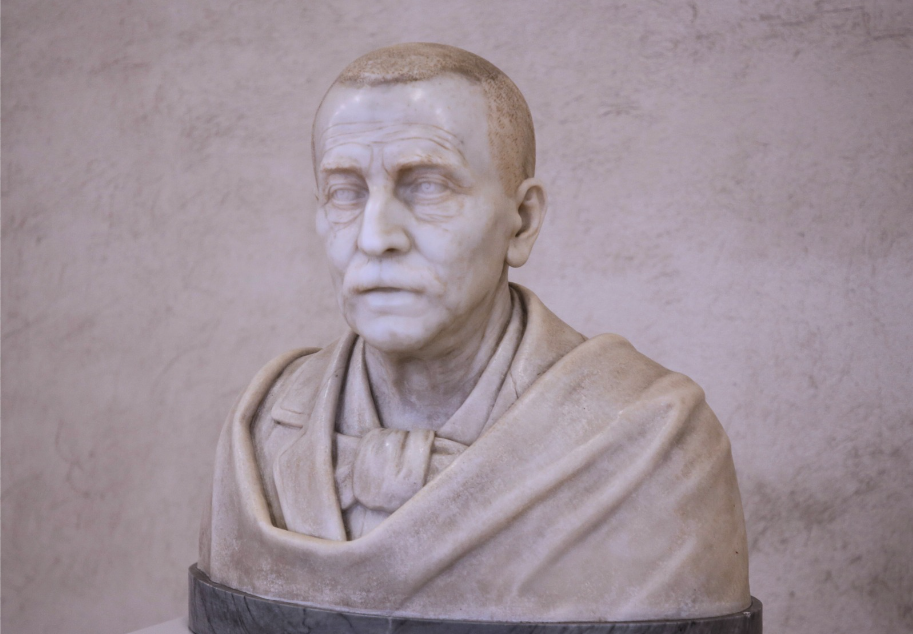

Yet the very idea of a “secular conservatism” is antithetical to conservatism itself. To champion a secular conservatism is to cut a branch from the tree and claim that the part is the real thing. “We know, and what is better, we feel inwardly,” wrote Edmund Burke in Reflections on the Revolution in France, “that religion is the basis of civil society, and the source of all good and of all comfort.”

A few years later, George Washington in his farewell address cautioned that “of all the dispositions and habits that lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports.” John Adams in his inaugural address agreed that “knowledge, virtue, and religion” are “the only means of preserving our Constitution from its natural enemies.”

Russell Kirk encapsulated this sentiment in his Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Conservatism: “Not all religious people are conservatives; and not all conservatives are religious people. . . . All the same, there could be no conservatism without a religious foundation.” The transcendent moral order that binds the present to the past and the future can only exist because a transcendent creator God has established it, and within it follows parameters of right and wrong, of good and evil, that a commonwealth exists to serve and conserve.

Kirk continued:

A society which denies religious truth lacks faith, charity, justice and any sanction for its acts. Today, more perhaps than ever before, Americans understand the close connection between religious conviction and just government, so that they have amended their oath of allegiance to read, “one nation, under God.” There is a divine power higher than any political power. When a nation ignores the divine authority, it soon commits the excesses of fanatic nationalism, intoxicated with its own unchecked power, which have made the twentieth century terrible.

The critical question for the twenty-first century is whether this traditional, religiously based conservatism is viable in a rapidly secularizing America. Moreover, given that social and political conservatism act in an arena outside of churches, one can ask whether conservatism’s religious foundation is functionally irrelevant to culture wars and public policy.

Precisely because, as Kirk wrote in The Conservative Mind, the first concern of the conservative is not with political battles but with “the regeneration of the spirit and character—with the perennial problem of the inner order of the soul, the restoration of ethical understanding, and the religious sanction upon which any life worth living is founded,” religion remains vital to a healthy conservatism even in a land where religious practice is currently waning.

Religion provides both a broad metaphysical framework for a coherent, principled conservatism and an internal inspiration for conservatives to order their own souls, their families, their communities, and their country. From this religious foundation, social conservatives can fight any culture war engagement or public policy battle, regardless of how far away from the action this base may seem.

How Religion Benefits Conservatism

Modern conservatism has never been agnostic. It is the defense, preservation, and continuation of the moral order shaped by belief in the Christian God. The French Revolutionaries were not fools: they knew that overthrowing this order required banishing God.

“Each contract of each particular state,” Burke wrote in the Reflections, “is but a clause in the great primeval contract of eternal society . . . connecting the visible and invisible world, according to a fixed compact sanctioned by an inviolable oath which holds all physical and all moral natures, each in their appointed place.”

Kirk summarized Burke’s ethereal vision in his first “canon” of conservative thought: “Belief in a transcendent order, or body of natural law, which rules society as well as conscience. Political problems, at bottom, are religious and moral problems.” The goods, the “permanent things,” that conservatives cherish—religion, family, community, rule of law, liberty, custom—all cohere and receive their orientation from the creator God who governs all things.

Following Jacobinism, other newfangled ideologies have risen to subvert the Christian moral order: Marxism, materialism, progressivism, secular nationalism, communism, fascism, multiculturalism, internationalism, and now wokeism. Though different in their specific goals, these ideologies have typically attacked belief in God, the one power preventing them from establishing total domination of the state over human life.

It is ironic that the Christian moral order’s avowed enemies on the left have long understood what some partisans today on the right do not: that religion’s first gift to conservatism is the creator God to whom all people and things are subjugated. Religion’s second gift flows directly from this: human beings, as God’s creations, possess their own inherent dignity, which no other person, state, government, or entity can take from them. This dignity is reflected in human beings’ innate freedom, which they exercise through acts of the reason and the will. It also has a political dimension, which the modern world calls “human rights”: life, family, liberty, and property are natural to human beings, and therefore no government or other being may infringe upon them, as the aforementioned ideologies have all sought to do. The state exists to protect these rights; it does not endow them.

Christianity opposes any efforts to remove God from the social order; the subordination of human beings to the state would be one swift consequence of that removal. As Christopher Dawson explained in Religion and the Modern State: “Christianity is bound to protest against any social system which claims the whole of man and sets itself up as the final end of human action, for it asserts that man’s essential nature transcends all political and economic forms. Civilization is a road by which man travels, not a house for him to dwell in. His true city is elsewhere.”

The sovereignty of God over human beings frames the social order and guarantees the rights of all human beings within it. These facts are not irrelevant abstractions, for from the exaltation of God follows the worship of God that religion exists to facilitate, and with it comes the third benefit that religion provides conservatism. Religion incarnates beliefs about God into the social order, chiefly through worship but also through a host of other cultural developments: art, music, architecture, literature, and festivals of celebration (consider the cultural rituals surrounding Christmas, Easter, Valentine’s Day, and other saints’ days).

From the Christian religion also comes the charitable impulse that has been institutionalized in ways that were once revolutionary, but which today Westerners deem to be hallmarks of civilization: hospitals, orphanages, adoption agencies, schools, homeless shelters, and groups that protect women and children. Religion enriches a creative and humane culture while simultaneously providing an enduring motive for preserving it.

A fourth benefit religion confers on conservatism is to sanctify the permanent things of family, community, law, and custom that exist in nature but are exalted by divine favor. The permanent things could command esteem merely because they precede other human-made institutions chronologically, but religion imbues them with a sacral character that both protects them from state encroachment and enhances their standing among human beings. This sacral character also motivates political action: the more valued the cause, the more likely citizens are to rally to it.

Fifth, following the previous point, religion endows conservatism itself with supernatural vitality. The task of conserving the permanent things, of maintaining Burke’s vision of society as a contract “between those who are dead, those who are living, and those who are to be born,” receives both import and energy when seen from the perspective of God’s providence. Grace perfects nature by lifting it to God, whom it cannot reach on its own. Likewise, grace perfects conservatism by directing the permanent things toward their ultimate end.

Sixth, since religion directs human beings to God and is incarnated into the social order, it is itself a permanent thing that simultaneously provides community and corporate belonging for its adherents. Membership within a religious community can often prove more satisfying and enduring than memberships in other local organizations because of the higher and timeless vision that religion offers.

Finally, religion purifies conservatism of certain temptations of right-wing politics, particularly the misuse of power to dominate rather than to serve the common good. Just before his death, Jesus Christ affirmed to Pontius Pilate that the power of the state comes from God; political power, then, has limits. In The Conservative Mind, Kirk identified “two great virtues” as “the keys to private contentment and public peace: they are prudence and humility, the first pre-eminently an attainment of classical philosophy, the second pre-eminently a triumph of Christian discipline.”

Humility tames the vice of pride, whose poison fruit is the libido dominandi. Of course, conservatism, painfully aware that humility is the virtue of few, champions constitutional limits on political power to prevent its misuse. The Christian religion, with its doctrine of original sin, confirms conservatism’s thesis. Christianity’s insistence that the greatest among us must be servants of others offers an additional bulwark against using power to crush enemies, to excite utopian adventures, and to enrich rulers.

How Religion Benefits Conservatives

Conservatives also profit from religion as individuals and as members of communities. First, as Washington, Adams, and the Founders all believed, religion fosters the development of virtue and the curbing of vice more effectively than does any temporal motivation. A functioning republic depends on individuals first governing themselves. As Tocqueville observed, “The safeguard of morality is religion, and morality is the best security of law and the surest pledge of freedom.”

Virtue enables individuals to govern themselves and to exercise their freedom in a way that enhances their own lives and communities. Religion especially motivates the virtue of charity toward neighbors and toward the needy. When virtue regulates self-interest, individuals and communities can better protect and pursue the common good.

Second, religion powerfully shapes marriage and family life, the cornerstones of the political order. By elevating marriage from a natural institution to a sacred one blessed by God, religion provides added motivation for spouses to honor their vows and one another. Religion dignifies children as the crown of marriage and orders family life toward the fulfillment of members’ supernatural vocation.

Third, religion motivates conservatives to cultural and political action. If Kirk is right that political problems, at bottom, are moral and religious problems, then the “culture wars” that have raged in America for half a century concern two different moral and religious visions, the Christian and the secular. Issues such as abortion and same-sex marriage and battles over race, gender, immigration, and parental rights are all moral questions that receive their political answers depending on their advocates’ religions.

For many conservatives, religious belief serves as the primary motivator to take up their chosen cause. The most poignant illustration of this is on display each January at the annual March for Life in Washington, D.C., where tens of thousands combine political demonstration with prayer. Religion mobilizes countless pro-lifers to such a degree that they spent decades laboring to create the legal conditions for Dobbs v. Jackson to overturn Roe v. Wade.

Finally, religion’s emphasis on morality and supernatural hope can prevent conservatives from falling prey to far-right groups that are conspiratorial in nature and fundamentally not conservative in orientation. Such groups, since they have lost sight of God and the moral order, mistakenly believe that the survival of the nation depends on their own action, and any action may be permitted to reach their goal. Religious conservatives, by contrast, know that, while they must labor to preserve what is good in this world, the world and all things in it belong to God, who alone has the power to judge. A conservative’s actions, no matter how urgent, are always tempered by the knowledge that this world will never be perfect and that it is not the end of the story.

Conservatism, Non-Christians, and Nonbelievers

Acknowledging the immeasurable value of religion to society is incumbent upon all conservatives. Believing in and having a personal relationship with God, as Kirk mentioned, is not. It is possible for non-Christians and nonbelievers to be conservative because the permanent things they cherish function within the social order, not the supernatural order. Conservatism has a persistent temporal orientation that appeals to all kinds of people, be they of another faith or no faith at all. For this reason, the conservative movement has always been ecumenical in character, and it has received invaluable contributions from Jews and nonbelievers over many decades.

If the conservative movement were to cut ties with religion, it would prompt its most loyal adherents to reconsider their participation.

Though the permanent things are fruits sprung from roots planted deeply within Christian soil, it is possible to love these fruits and defend them from aggressors without agreeing about their roots. In these acts of loving and defending, nonbelieving conservatives can lock arms with believers of all faiths. This is not an attempt at “fusionism,” for believers and nonbelievers labor to conserve the same things; their disagreement concerns the source, guarantee, and orientation of these things. But because strong roots are essential to the health of the tree and its fruits, conservatism cannot not flourish if too many conservatives ignore the roots.

In How to Be a Conservative, Roger Scruton expresses discomfort with “many American conservatives” who believe that “the conservative position rests on theological foundations.” He prefers the British approach, which, while recognizing the value of religion for aiding individuals and forming communities, “is built upon purely secular principles.” British conservatives do acknowledge that “much that we value is marked by its religious origins,” but they insist that they can “depend on the realm of sacred things even without necessarily believing in its transcendental source.”

Liberalism, after a century of experimentation in separating the permanent things from their sacred source, offers a cautionary tale. It has had some successes in embracing the humanitarian elements of Christianity while rejecting Christianity itself. The civil rights movement was a triumph of the American political left, though religion was certainly a motivating impetus in its early days. More recently and less religiously, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, though enjoying bipartisan support, was championed primarily by the Democratic party.

But as liberalism grew more distant from the Christian moral order, liberals began to demand rights not just for individuals but for sexual and sex-changing practices once universally judged to be immoral. Feminism and women’s rights followed the same trajectory: once Christianity was tossed aside, liberals perilously adopted abortion as the sine qua non of women’s rights. Laws that cover everything from divorce to child rights to the nature of marriage itself have been transformed as expressive individualism replaced Christian morality as the underlying philosophy that shapes them.

A healthy conservatism balances the inevitable forces of change against the wisdom of permanence. To discard Christianity for a secular conservatism would wrench change from its counterweight; change unbound becomes a force of destruction. Such could be the fate of the permanent things isolated from their religious sanction. “A society which has lost its religion,” Christopher Dawson cautioned in Progress and Religion, “becomes sooner or later a society which has lost its culture.” Spiritual change can alter society not only from the left, but from the right.

The Viability of Religious Conservatism Today

If religion is integral to conservatism as a governing, sanctifying, and animating principle, what is the status of the conservative movement as Americans grow more indifferent to religion? Is a religious conservatism even viable given the rising number of “Nones,” Americans claiming no religious affiliation, especially among the Millennial and Gen Z cohorts?

The failure of “old religious conservatism” stems less from a style of politics and more from a failure of Christian conservatives to live their religion with conviction. The same can be said for the decline of American religion more broadly: too many believers and religious leaders have failed to live what they profess, and the stench of hypocrisy repels even the most loyal believers.

For the American public, same-sex marriage, to name the most prominent example, was transformed from a contradiction in terms into a celebrated institution because too many conservatives acquiesced to the allure of the sexual revolution, which decoupled sex from procreation and robbed marriage of its permanent, sacral character. Had Christian conservatives loudly rejected the revolution while championing the blessings of children and family life, it is quite possible that Pride Month would not be featured on public and corporate calendars today. Had Christian conservatives mustered an imaginative effort, “family is love” could have been as compelling a marketing campaign as the tautological, and triumphant, “love is love” campaign.

Does the failure of Christian conservatives to live their faith, combined with so many Americans leaving theirs, strengthen the argument of those who desire a secular conservatism? No. First, survey data show that religious Americans are more engaged in their communities and in politics than nonbelievers. If conservatives are to win battles in the public square, they need soldiers to show up. If the conservative movement were to cut ties with religion, it would prompt its most loyal adherents to reconsider their participation.

Second, a secular conservative forfeits a tremendous inheritance in considering moral and political problems. A person may well be “anti-left” or “anti-woke,” but that position is hardly unique to conservatives, and by itself it is not enough to win the battle. Moreover, conservatism is not defined by what it is against but by what it is for.

Many have called wokeism a religion, and as such it cannot be defeated by rational argumentation alone. Only another religion can oppose it successfully, and that is Christianity. To win the culture wars, conservatives need to recapture their religious zeal. Their authentic, personal witness can help revive religion’s standing among the Nones by convincing them of religion’s positive benefits to individuals and to society. Within the public square, not every conservative argument must be made on religious grounds, yet conservatives would be foolish to ignore the divine. The pro-life movement, for example, has successfully changed minds with scientific and philosophical defenses of the unborn child’s right to life. But it has changed hearts when it has presented the child as a gift from God and human life as sacred—these are religious arguments.

Today defending the permanent things ought to include evangelization for a joyful Christianity that cogently answers today’s questions about meaning, purpose, and freedom. Given the darkness of contemporary secularism and the sheer madness of wokeism, such Christian apologetics is not a herculean feat. Those who engage in denominational infighting need not apply; in the vision of Tocqueville there can be “no religious animosity, because all religion is respected and no sect is predominant.”

Conservative publications and television news outlets should give more attention to religion and religious concerns. Currently, these concerns take a back seat to politics. Stories of prominent persons who have converted to Christianity from atheism or wokeism, the establishment of new religious schools and churches, survey data on religious practices, responses by church leaders to current events, reviews of religious books, and heroic acts of charity are just some religious topics that contribute to developing and promoting a religiously inspired conservatism.

Conservatives must reject the left-wing lie that religion is inherently divisive by reaffirming religion as a source of vitality, happiness, and meaning. Signs of such vitality are appearing across the nation in the classical school movement. These schools are often religiously grounded and teach a specific creed within a curriculum anchored in the Western tradition. They are perhaps today’s greatest example of how conservatism functions within the social order while receiving its shape and motivation from the supernatural order.

An imposition of religious principles onto the public order by direct legal force is destined to fail, in part because such a venture is not conservative. Rather, conservatives should continue legal and political challenges to overturn state-enforced atheism that masquerades as “religious neutrality.” To require prayer in public schools in secular America today would be a mistake; to open space where school prayer is legal and protected for those who desire it should be a priority. The same goes for discussing God and reading the Bible: classroom lessons on these topics neither demand belief nor impose a creed any more than lessons on communism or capitalism do.

Creating space for religion to grow organically in these institutions is the slow yet prudent approach to returning religion to public prominence. Given the attractive vision that authentic religion presents to a secular world mired in darkness, the promise of “if you build it, they will come” may well be fulfilled.

“Order in this world is contingent upon order above,” Kirk wrote in The Conservative Mind. If we are to restore order to our disordered republic, authentic conservatism inspired by religion remains the path forward, even in a secular age.