There’s a noisy debate going on about the H-1B visa program, one that involves immigration policy, economic growth, and workforce development in the United States.

Just what are these troublesome things? H-1B visas allow U.S. employers to hire foreign workers in specialized fields such as computer programming, electrical engineering, and medicine. Proponents of the program argue that these visas are essential for filling critical skill gaps in the American labor market, promoting innovation, and keeping the country competitive in the global economy. Many of the world’s leading tech companies rely heavily on H-1B workers. But critics raise concerns about the program’s potential to lower American wages, displace domestic workers, and create dependency on foreign labor.

It is notable that both sides of this debate are represented in the MAGA camp, with Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy defending the use of specialized visas (if perhaps not the current setup of the H-1B program), and longer-term supporters of Trump, such as Steve Bannon, arguing against it.

As happens so often in these debates—especially when they rage on social media—the partisans on both sides have put forth misleading arguments. The pro–H-1B camp claims that there is a “domestic worker shortage” in high-skilled tech jobs, while the visa opponents take it for granted that “lowering US tech salaries” makes Americans worse off. As we’ll see, neither of these claims, stated in such stark terms, makes economic sense. We won’t take a stand here on whether the H-1B program should be maintained as is, expanded, or scrapped, but we will give readers a more coherent framework for thinking about the tradeoffs.

Let’s first consider the members of the pro–H-1B camp. Their primary argument is that (allegedly) there simply aren’t enough home-grown Americans to fill the high-skill tech jobs needed to ensure U.S. competitiveness in the coming decades. Such proponents often say that tech companies need the ability to bring in foreign workers to alleviate the “shortage” of qualified Americans.

But let’s test out this language in a different scenario. Imagine that you go shopping for a diamond ring, intending to propose to your girlfriend. You have saved up $1,000, but when you head out to the jewelry stores, you are shocked to discover that a reasonably sized ring will run you $10,000 or more. You decide that there is a shortage of diamond rings and that we need a government program to do something about this terrible state of affairs.

Of course, this is nonsense: there are plenty of diamond rings available for anyone who wants to pay the market price. You simply wish that that market price were lower than it is.

What makes the price what it is? There are any number of factors, such as the difficulty of finding sources of diamonds. But there are also legal factors, such as laws banning the import of so-called “blood diamonds”—diamonds whose sale helps to fund an insurgency or civil war. If such import bans were lifted, the supply of diamonds in America would increase, and the price of diamonds at U.S. jewelry shops would fall. In your desperation to get a nice ring for your fiancée, you might start a political campaign advocating for the lifting of such bans: “America faces a critical shortage of diamonds: we need to import more to fill that gap!”

To be clear, bans on the import of so-called blood diamonds may or may not make sense; we aren’t taking a stand on that issue. But either way, the campaign slogan in our hypothetical story would be dishonest: the truthful slogan would be “I want to pay less for diamonds than the current market price, so let’s import more of them.” The case is similar with H-1B visa workers: whether or not you agree with restrictions on foreigners immigrating into the U.S., it’s an abuse of terminology to say there is a “shortage” of American-born tech workers. No, the reality is that U.S. tech companies don’t want to pay (or might be unable to pay) what the market rate would be to fill their tech slots if the H-1B program didn’t exist.

Some defenders of the H-1B program have claimed that the supply of computer programmers is not like the supply of, say, ditch diggers, because it takes so much time to train programmers. “It takes six years to get a B.A. and M.S. in computer science,” they argue, “and therefore it will take years for the supply of American programmers to increase in response to an increase in salaries offered.”

It is true that the supply of programmers cannot increase as rapidly as the supply of less skilled labor. Nevertheless, this counterargument is of very limited validity. For one thing, a requirement for any sort of computer science degree for a programming job is itself evidence of the large number of people who would like to work at such jobs. It is a filtering mechanism, not a necessary step in the training of a competent programmer. (See Bryan Caplan’s book The Case Against Education on this point.)

To be sure, formal computer science programs teach a lot of interesting things about the theory of computing, but almost nothing in that curriculum is necessary to be a competent programmer. The vast majority of the people who founded the discipline of computer programming had no computer science degrees, since, for the most part, these types of classes didn’t even exist when they were learning to program. For a new hire with reasonable aptitude, a couple of months of on-the-job training is sufficient to become a productive programmer. (One of us knows this is true, since it is exactly how his own programming career—with decades of experience in the financial sector and then academia—was launched.)

Furthermore, the argument citing the long training period ignores many marginal cases. There are any number of Americans who already can program and are not doing so today but would take up doing so if offered a sufficiently high salary. Examples include someone retired from programming who would go back to work if the salary offered were high enough; a competent programmer working in another field such as finance, physics, chemistry, or biology who would be motivated by a salary increase to switch to full-time programming, and STEM-adept workers entering the workforce and deciding on a particular discipline to pursue. (This “marginal analysis”—where U.S. workers have much better fallback options than foreigners desiring a master’s degree to gain easier access to the American job market—helps explain why, as of 2019, 72 percent of graduate students in U.S. STEM programs were foreign.)

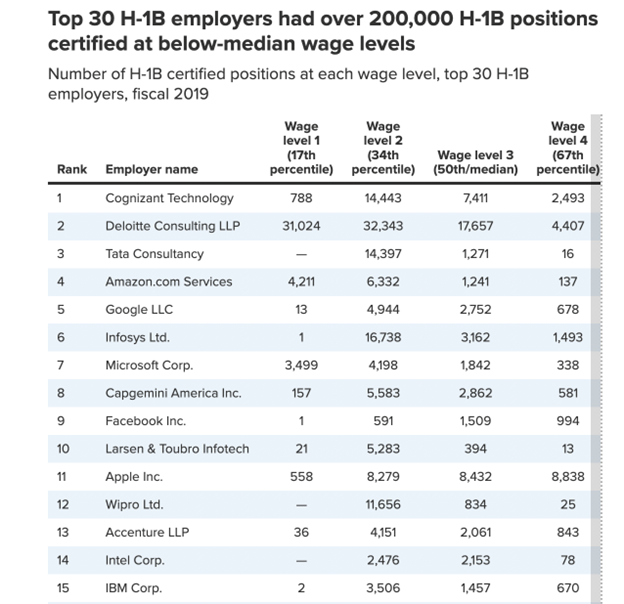

When we switch away from armchair theorizing and look at some of the data, it becomes clear that the H-1B program is a vehicle for U.S. firms to pay below the prevailing salaries for various occupations. This is an important point, since the H-1B program ostensibly has requirements for firms to pay at least the prevailing domestic wage. As this 2020 report (based on 2019 data) from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) explains, however, in practice the Department of Labor is quite liberal and allows H-1B applicants to pay below the actual median level for their region and occupation. Consider the following (abridged) table, reproduced from the EPI study, showing the top fifteen H-1B employers in 2019 and the distribution of their certified positions according to the local labor market wage levels:

Some readers might be confused by this table because they had thought the H-1B program was relatively modest in size, involving only 85,000 foreign workers. But that figure is the annual quota of newly issued slots. The total number of H-1B employees is some 600,000.

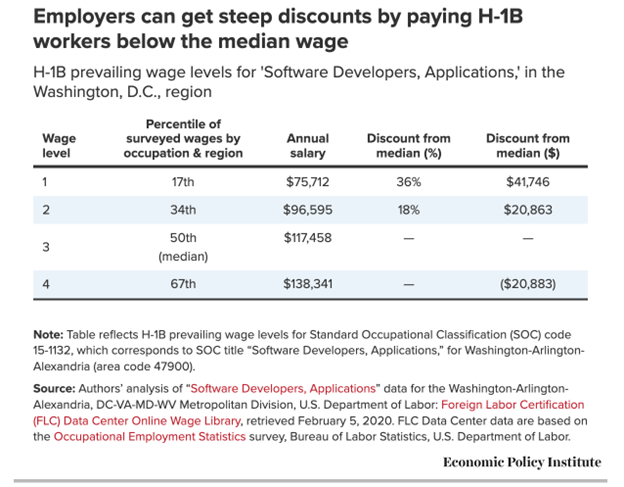

We should be clear that even though the majority of H-1B workers are paid at or below the median wage for their location and occupation, in absolute terms these are still high-paying jobs. For example, the same EPI report presents the following information on Washington, D.C.–based software application developers in 2019:

As these numbers indicate, both sides in the debate are making accurate statements: the H-1B jobs are high-paying slots for talented individuals, but they still are not as high-paying as comparable slots staffed by Americans.

Now that we have spent so much time poking holes in the standard pro–H-1B arguments, we can very quickly make one important point regarding the critics of the program. Their main objection is that the H-1B program’s true purpose is not to recruit elusive superstars from around the world but rather to bring in standard workers (who admittedly have tech skills) and pay them lower wages than comparable Americans would require. Many of the critics of the program seem to think that this alone proves that the H-1B system makes Americans poorer.

Rather than focusing on the impact of reduced wages, it would be more accurate for the opponents of the H-1B program to emphasize the simple fact that limits on immigration exist for a reason.

But this too fails basic economic analysis because it only looks at one side of the equation. Yes, other things equal, if a U.S. firm can hire cheaper foreign labor for certain jobs, that option will hurt the American workers who now will have to accept a pay cut or find work in a different sector. But lower costs also translate into lower prices (or better products) for American consumers. If we focus purely on the economics of wage levels, importing foreign labor is equivalent to importing foreign goods, and we have the standard argument of free trade (which can hurt certain U.S. workers but in general benefits American consumers).

Rather than focusing on the impact of reduced wages, it would be more accurate for the opponents of the H-1B program to emphasize the simple fact that limits on immigration exist for a reason. To return to our “blood diamond” analogy from above: The ban on such imports might be a good idea or a bad idea, but it would be missing the point to argue about a diamond shortage, on the one hand, or to claim that cheap imported diamonds will just hurt married American women by depressing the resale value of their rings, on the other. No, the issue is whether it’s good policy for the government to restrict the importation of diamonds tied to criminal activity; market prices will adjust to the situation once the policy is set.

So too when it comes to the H-1B program and immigration policy in general. There are many issues involved, on which we do not take a stand here. But once the caps on various types of immigration are set, U.S. wage rates will adjust accordingly. As far as the pure economics go, everyone in the debate should be aware of the basic facts: if the H-1B program is curtailed (or outright eliminated), then wage rates in the relevant occupations will rise so that the quantity of workers supplied will still equal the quantity demanded; there won’t be a “shortage.” On the other hand, these rising wage rates for American-born workers won’t be a pure boon to the citizenry because then American consumers would have to pay higher prices for the output of the affected firms.

Any society benefits from some openness to new members, who bring with them new ideas and skills, or it will tend to stagnate. At the same time, any society that does not have a sense of solidarity among its already existing members will tend to fragment into the “atomic individuals” of social theory. Economic science can help us quantify some of the tradeoffs involved, but it cannot tell us how to balance these competing values.