In 1920, with the publication of R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), the Czech writer Karel Čapek invented the idea of an artificial worker created by human beings. For Čapek, the essential thing about robots is their teleology: they are created to work. As such, once they are employed by human beings to do their work for them, humans themselves become dispensable. Lacking a purpose for being, human fertility collapses, and we are destined to wither away. All the robots truly need in order to replace us is a sense of agency and a purpose outside of work for their dying masters, one rooted in love and care for one another.

That essential irony—by creating robots, humans make themselves obsolete, but robots will need to become human in an emotional sense in order to truly supersede us—appears over and over again in subsequent robot stories. These stories are never truly about robots, but about ourselves: the changes we perceive in ourselves and our technology-driven society and the changes we need to make to survive or overcome them. Over time, however, the locus of identification in these stories has shifted. Where once we instinctively identified with the humans, increasingly we identify with the robots. The android-hunter hero of the original Blade Runner is (contra fan theories that posit otherwise) a human being who, like us, comes both to appreciate the pathos of the androids’ created and enslaved condition and to wonder at the possibility that they might transcend it and become fully (indeed, more than) human. But the hero of the sequel, Blade Runner 2049, is himself an android, as are his primary antagonists. He’s in love with an A.I., and his creator turns out to be the miraculous offspring of human and android. Human beings are almost incidental.

Is this because Čapek was right, and the more meaningful activity we hand off to machines the less meaningful our own lives feel? Or is it because by inhabiting a physical and social environment oriented around machines, particularly “thinking” machines like computers, robots and artificial intelligence, we ourselves become more and more robot-like? Three recent works of art—a disturbing blockbuster animated children’s movie, a deeply sad but life-affirming Broadway musical, and a delightful dialogue-free animated indie film romance—provide an opportunity to assess the current state of human–robot relations, and of our own transformation, at least as we human beings perceive it.

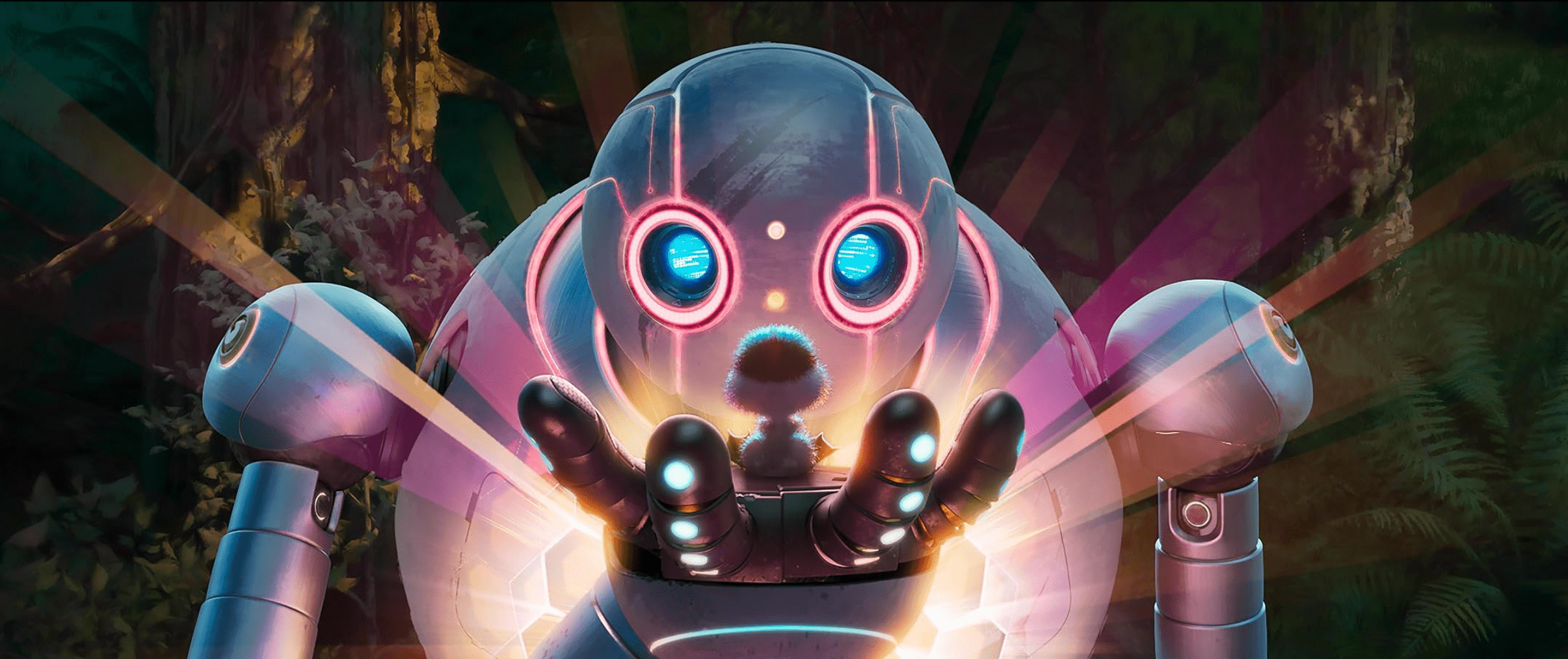

For most of its dazzling, breakneck-paced 102 minutes, The Wild Robot (written and directed by Chris Sanders, based on the book series by Peter Brown) seems like a fairly straightforward tale. It’s an alien-comes-to-Earth story—in this case, a robot that comes to the wilderness, and thereby to the experience of love, exemplified by parenthood. It’s like a cross between Starman and Horton Hatches the Egg. It also seems to be an allegory of our own alienation from nature and a call for us to return to the wild. In fact, it’s something quite different: a document of that alienation whose ethos would utterly transform nature itself.

A handful of humanoid robots are shipwrecked and wash ashore on an uninhabited island. One—ROZZUM Unit 7134 (voiced by Lupita Nyong’o), the name a clear allusion to Čapek—accidentally boots up and proceeds to search for its owner in order to acquire its first task. A robot, after all, is nothing without a task. But at first it cannot communicate with the island’s animal inhabitants, and even after it learns their languages (much as a large language model does, simply by listening to endless chatter), the animals cannot fathom what it could possibly want from them. The robot suffers both humiliation and damage as it comically bounces and flops around the rocky, forested landscape; is struck by lightning; and, as it tumbles, crushes a goose’s nest, leaving only a single egg intact.

Adoptive parenthood of this orphaned egg transforms the robot, introducing it to love, which enables it to transcend its programming. Upon hatching, the gosling imprints on the robot as its mother (nature’s programming at work). The robot decides that it has finally found a task: first to protect this vulnerable creature (whom it names Brightbill, voiced, once it is old enough to speak, by Kit Connor), to nurture it and to rear it to adulthood, and to prepare it—despite its having been born a runt—to face the challenge of migration. In the process, the robot, now called Roz, forms relationships with other animals of the forest, most prominently a fox, Fink (Pedro Pascal), who is wise to the ways of the wild, and an opossum, Pinktail (Catherine O’Hara), who has long and weary experience with parenthood.

It’s a story with charming potential to reflect on the ways in which parenthood is not a task analogous to corporate work and to satirize contemporary helicopter parenting in favor of a free-range childhood. But Roz is as intensely involved a parent as any in Brooklyn, and the call it hears from the wild is not to let be but to reform.

Roz becomes sufficiently attached to Brightbill that, even when its task of nurturing is done, it sticks around to see whether he will make it home after the winter, which proves to be harsh. During a blizzard, Roz takes upon itself the task of saving the freezing wild creatures, bringing them into its fire-warmed stone home. This motley crew did not evolve to cohabit, so before powering down (its own version of hibernation), Roz instructs them all, predators and prey alike, to maintain a truce until the winter is over, and they do. After the thaw, the beasts joke about resuming the struggle for survival, but we’re clearly meant to believe that somehow the experience of winter solidarity has enabled these wild animals to overcome the need for predation entirely.

It’s a strange turn in that it takes us decidedly away from wildness and toward, well, civilization. Is this a wild robot, I wondered, or a civilizing one? And what could the latter mean when confronting animal nature?

Martha Nussbaum’s Justice for Animals seems like the essential text for understanding what the film is doing here. Nussbaum promulgates a kind of “responsibility to protect” doctrine for human relations with the natural world. It is not enough for human beings to learn how to appreciate wild places and creatures and allow them space to thrive, nor is it enough for us to cease abusing the domesticated creatures we purport to cultivate or to stop fouling our common planetary nest. Just as in our relations with humans, our ability to prevent pain and suffering implies an obligation to do so. The wilderness—as Roz learns—is a place of rampant suffering and predation. We therefore have an obligation to change nature itself, as we have, purportedly, changed our own: to eliminate predation and privation in the wild and turn nature into nurture.

This, it seemed to me, was the mission Roz had embarked upon, and in retrospect I saw it reflected in its anything-but-wild approach to parenting. It is a moralistic fantasy of absolute control over creation, the ultimate endpoint of a mechanistic rights-based utilitarianism that has underlain all posited robotic ethics since the promulgation of Asimov’s three laws. (First, a robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm. Second, a robot must obey orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law. Third, a robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.) It’s also a bit hard to differentiate from the ethos of the only human habitation we ever see in the film, and which we are intended to loathe: a domed-in, sparkling clean city surrounded by orderly rows of plants. Brightbill and his fellow migrating geese shelter there during their migration, only to be attacked by the robots charged with defending it; this violence and its aesthetics tell us this place is evil. It is evil, we are told, precisely because it is predatory. Yet if a vision of controlled order is not where Roz’s nascent peaceable kingdom leads, then how will its predators be fed, its population kept within sustainable numbers?

Perhaps this is overthinking a story for children. But I’m not sure. The Wild Robot does seem to come bearing a message; the only question is what that message is. The anti-humanism of the film is obvious; there are no humans in the wilderness and the city is not only soulless, paranoid and hostile to life, but its human denizens remain invisible throughout the entire film. We’re also given powerful tokens of human vanity: one of the most beautiful shots in this visually stunning film is of a pod of whales swimming over the Golden Gate Bridge, now sunk beneath the Pacific. The human beings of this world have aimed to live apart from nature, but we are less and less relevant to our own creation, and nature survives while humanity’s greatest works are washed away.

But The Wild Robot cannot truly abide nature either, not as it is, red in tooth and claw. Roz takes to the task of nurturing Brightbill and helping him grow but never comes to grips with death and decay nor with the necessity of predation. Its own source of sustenance is mysterious; at one point in the film, it survives the literal removal of its own heart. And, of course, it is able to overcome its own programming through sheer determination and expects the animals to do the same. There’s something distinctly childlike—and very contemporary—in Roz’s easy conviction that it can accomplish any task and in its rejection of tragic necessity. Roz is an exemplary organization kid, and even as it becomes a parent, it never really seems like an adult. But the film flatters this perspective, giving Roz powers that are almost godlike.

Where will this godlike child lead us? The final act of the film sees the manufacturer send its robot goons to recapture Roz and restore it to its original factory settings, erasing its newfound sense of self and its attachment to Brightbill and the other creatures. But though Roz is captured and its memory erased, Brightbill leads the animals to defeat the robots and recover Roz, who is then effectively resurrected, regaining its memories at the first sight of its adopted child. Assured, now, of its ability to transcend digital death, Roz submits to the manufacturer and returns to civilization (thereby sparing the animals further attacks).

It’s a sequence with obvious Christological overtones. But Roz, unlike the alien in E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, is both a self-made messiah and our primary locus of identification; we’re not to imagine ourselves receiving a message but becoming the messenger. And in the last scene of the film, we see how it will spread its gospel. Brightbill infiltrates another domed human settlement where Roz works in the hydroponic fields. The manufacturer clearly believes that Roz has been erased, but the moment it is reunited with Brightbill both he and we know that Roz remembers, that the nightmare of A.I. non-alignment has come true, and that it has its own harvest to make among the robots alongside which it labors.

The moment is eerily reminiscent of the final shots of Richard Linklater’s film A Scanner Darkly, based on the Philip K. Dick novel of the same title. That story’s hero, Bob Arctor, having become so thoroughly addicted to Substance D that his mind has been erased, is put to work cultivating the very drug that destroyed him. The corporation he works for had, supposedly, aimed to cure him, but this reveals that it is actually responsible for his and everyone else’s addiction. Yet the sentiment of the scene in The Wild Robot radically reverses that of the Linklater film. Arctor learns the truth too late to do anything with the information since his mind is gone. Roz only feigns submission while secretly plotting revolution on behalf of the wild.

But is it really on the wild’s behalf? I couldn’t help but feel that if Roz and its robot fellows ever displaced their human creators, the new boss would be much the same as the old boss, that the kind of love it has learned is as controlling as ours has become. For all that the film’s digital recreation of the wild is genuinely awe-inspiring, all through the screening I felt the chill of a metallic hand pressing me firmly down into my seat.

Like Roz in The Wild Robot, the protagonists of the musical Maybe Happy Ending (music by Will Aronson, lyrics by Hue Park, and book by both Aronson and Park) are robots without tasks. They frequently seemed to me like stand-ins for our fellow humans, at least those of us who have increasingly come to internalize the task-focused robot ethos. But Maybe Happy Ending touched my heart deeply in a way that The Wild Robot didn’t.

The story focuses on two obsolete “Helperbots,” Oliver and Claire (Darren Criss and Helen J. Shen), robots who are designed to be personal servants to human beings—similar to Klara, an Artificial Friend who is the protagonist of Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel Klara and the Sun (which I discussed in the Summer 2021 issue of Modern Age). Now obsolete, they reside in an SRO designed for them to wait out the remainder of their “lives,” ordering replacement parts until their manufacturer stops making them and they inevitably cease to function. From the beginning, then, we are in a world touched by the tragic necessity of death, even for robots.

We also begin in a state of denial. We first meet Oliver, a Helperbot-3, as he goes through his daily routine: greeting his potted plant, HwaBoon, receiving his copy of Jazz Monthly, listening to classic jazz in vinyl on a vintage record player (his room is impeccably decorated in a mid-twentieth-century style). He inquires whether there is any message from his former owner, James, and, learning that there is not, reassures HwaBoon and himself that James will surely come soon to bring him to his owner’s new home on Jeju Island. We watch in mounting horror as Oliver does the same thing for twelve years, until his routine is suddenly disrupted by Claire, a Helperbot-5 (a more technologically advanced model than Oliver but now just as obsolete) who lives across the hall and knocks on Oliver’s door asking to borrow his charger because hers is on the fritz.

I feared at first that this meeting was almost too cute, because these robots felt a lot like people I had met before. Oliver is a harmless but persnickety nerd who likes to keep his space just so, the kind of character Steve Carell played in The 40-Year-Old Virgin. Claire, who dresses as an approximation of a Korean twentysomething and whose room is lit by pink neon and decorated with a single fuzzy pink poof, seems like she might be just the kind of manic pixie dream robot to open Oliver up to the possibilities of living, and/or the woman of the world who needs to be reminded by Oliver about the joys of innocent wonder. Maybe Happy Ending does play both tunes, but its true mode is deeper and more melancholy, with much to say about how robots have already changed us, and how much we have become like them.

Oliver isn’t a recluse afraid of human contact; on the contrary, he already believes he has a best friend: James. That relationship doesn’t feel to him like a task; it feels like love. But while both we and Claire (who understands humans far better than Oliver does) can see that Oliver’s devotion is not reciprocated and that James is never coming for him, Oliver genuinely does not. Claire is drawn to him by her simultaneous (and conflicting) desires to help him get over his fixation on the past and to protect him from the painful truth of his abandonment.

Discovering that Oliver has been secretly collecting cans to pay for a ticket to visit James, Claire decides to cut to the chase. She takes Oliver on a road trip in her car (a parting gift from her former owner—Helperbot-5s are allowed to drive) to James’s home on Jeju Island, where the world’s last fireflies—nature’s robots, so they think—can also be found. They have to stop partway at a sex hotel to recharge, an opportunity for comical misunderstanding (the musical is, in general, very funny), and while Oliver is powered down Claire reads his memories, learning that James did, in fact, abandon him, and then erased Oliver’s knowledge of that fact. Confirmed in her suspicions, when they get to James’s home, Claire tries to prevent Oliver from approaching him and learning the truth. To explain why, after confessing her transgression in reading his memories without his permission, she shares hers with his—specifically a scene in which her owner’s husband makes a pass at her, saying she understands him better than his wife does, a memory that the husband deleted but that her owner restored upon “retiring” her.

This, then, is the reason for Claire’s distrust of humans. As a plot point, it reflects a wise appreciation on the part of Aronson and Park for how “intelligent” robots will deform our relationships with humans. But those deformations are not really new. “You understand me better than my wife does” is a story as old as marriage; what’s new is less the fact that the one who understands is a robot than that both husband and wife know that the robot is a mere thing, and literally dispensable. Yet Claire’s owner restores her memory, treating her to that degree as a person endowed with dignity.

This theme is recapitulated when we learn why Oliver himself was abandoned. James’s adult son, Junseo (played by Marcus Choi, who also plays James in flashback), arrives just after Claire’s revelations and tells Oliver both that James has been dead for years and that he, Junseo, was the one who had made his father give up his Helperbot. Junseo had grown up filled with jealousy of his father’s perfect replacement son, so when his father grew ill and wanted to move in with him on Jeju Island, he demanded that his father leave Oliver behind. Junseo’s bitterness is palpable as, before sending Oliver and Claire away, he hands Oliver a gift left him by James: a precious jazz record that he especially loved.

The mix of betrayal and lingering affection is nothing if not human, and the revelation changes both robots, dispelling Oliver’s illusions (James not only abandoned him but thought he’d be happier living a lie of anticipation rather than knowing the truth) but relieving Claire of her cynicism (Oliver’s feelings were in fact reciprocated, as proved by the gift), and prompts them to make a go of loving one another. Back at their SRO, they perform a hilarious simulacrum of a human relationship, attempting chaste kisses and even staging a mock lovers’ quarrel.

Hovering in the background, though, is the knowledge of loss. They’ve found a purpose to existence now—caring for each other—but it’s tenuous, as Claire’s battery holds a charge worse and worse every day. Within the year she’ll shut down for good. (Oliver, as an older model, is more durable and probably has a few good years left in him, albeit without Wi-Fi since that chip is broken.) I won’t spoil the ending, but the ability to erase and recover memories—which is to say, to forget and to remember—proves to be, as Homer Simpson said of alcohol, both the cause of and the solution to all of life’s problems, not only for Oliver and Claire but also for Junseo.

The show is an absolute heartbreaker, and I surely haven’t done it justice by focusing on the plot rather than the humor—or the lovely music, sung both by the principals and by Dez Duron as the midcentury jazz crooner Gil Brentley of Oliver’s records—or especially the extraordinary staging, which makes the best use of modern stage technology that I can recall, including a neon-edged iris that sometimes frames a single room and sometimes opens up to expose a whole city, along with prerecorded black-and-white video of the robots’ memories with which the live actors interact with impressive fluidity. Michael Arden (director), Dane Laffrey (scenic design), Ben Stanton (lighting design), Peter Hylenski (sound design), and Clint Ramos (costume design) all undoubtedly will be nominated for Tony Awards; they certainly deserve to be.

But as my heart broke, I was also comforted to know that even robots could make such beautiful music alone together.

The love story in Robot Dreams, written and directed by Pablo Berger and based on the graphic novel by Sara Varon, isn’t between robots or between people. It’s between a robot and a dog. Well, kind of. The dog has an apartment in the East Village, not normally something a dog can rent on its own. Meanwhile the guy playing the drums on the subway platform is an octopus, the junk man is an alligator—clearly, we are intended to see all of these beings as people. Still, there is a difference: most are animals, but some are robots. Why?

The film can be enjoyed without ever asking, much less answering, that question. It is a veritable cornucopia of cinematic pleasures. Start with the nostalgia it will provoke in anyone who remembers New York in the 1980s, the period in which it is set; even considering the deterioration in public order since the end of the Bloomberg administration, the city is considerably safer and more prosperous than it was then, but the exuberance, liveliness, and color on display in this film reminded me of the distinctive joys of that time (or perhaps merely of my own youth). Continue with the old-school animation style, a throwback to the same era. I was far more charmed by its densely detailed and homey pleasures than by the more spectacular effects of The Wild Robot. The film is a master class in visual storytelling; it has to be, as there is no dialogue—though that doesn’t imply silence. The city is alive with sound, and music plays a key role not only in providing ambience but in telling the story.

That story is filled with deeply human joy and melancholy. When we first meet our protagonist, he is lonely, sitting in his modest apartment watching television and eating microwave dinners every night. He longs for companionship. What’s a dog to do? He sees an ad for a home-built robot kit, and in no time at all he has a bosom friend, someone who delights in every new experience and wants to spend every minute with him. Dog is in heaven.

After only a day of ecstasy, though, disaster strikes. Dog takes Robot to the beach at Coney Island, but they stay out too long, and Robot both rusts from the surf and runs out of power. He’s too heavy for Dog to drag home, so Dog leaves his friend on the beach, returning the next day with tools to fix him only to find that the beach is closed until the following season. Dog, distraught, tries to break into the beach, but is caught and thrown in jail. Sadly, he resigns himself to waiting nine months—a pregnant span of time—to retrieve his friend.

The bulk of the film depicts Robot’s dreams and experiences as he waits. He is frozen in ice and has elaborate fantasies of escape that are dashed on the shores of reality. He’s visited by seafaring rabbits who steal his leg and by a mother bird and her fledglings whom he helps to learn to fly by subtly flapping the line of his mouth. Finally, with the spring thaw come the beachcombers, one of whom (an ape) finds Robot buried under the sand, digs him up, and carts him off to the alligator junkman, who, like Miss Trunchbull from Matilda, hammer-tosses him onto the pile of scrap, breaking him into myriad fragments and causing his eyes to finally wink shut. When the beach opens in June and Dog races to retrieve his friend, there is no sign of him, above or below the sand. Dog leaves despondent.

Yet this isn’t the end for Robot—or for Dog’s chances of happiness. A raccoon named Rascal who works as an apartment building superintendent comes to the junkyard looking for parts, impulsively picks up Robot’s head, and builds him a new body out of a boom box. Dog, meanwhile, happens by a store selling used appliances, including an old robot named Tin, and buys him; soon he too is happily matched. Our two protagonists have found new loves—and then, just when we’ve gotten used to their having moved on, they seem to be about to find each other again.

The climactic moment of the film comes when Robot is on Rascal’s roof for a barbecue and sees Dog and Tin walking along the street. He feels compelled to run downstairs and reconnect with his old love—that scene plays out in another fantasy—but instead he plays their signature tune (Earth, Wind & Fire’s “September”) and dances, out of sight. Dog, hearing the song down on the street, also dances with abandon, remembering his lost friend, but never sees him. It’s their last dance “together,” but only Robot knows that is what it is. Afterward, Robot, still hiding, watches Dog walk away, initially sad, then consoled by Tin, and returns to the barbecue and to Rascal, who made it possible for him to play music from his torso in the first place.

It’s a straightforward rejection of the expected romantic comedy ending. When the film was over, my wife asked me whether it struck me as sad or happy, and the answer of course is both. But it is also the answer to the question, “Why a robot?” The promise and peril of robot companionship is that of relating to a being who was literally made for us—but that romantic myth is older than Pygmalion and Galatea. Robot doesn’t move on, and allow Dog do the same, because he loves somebody new, but because he loves somebody differently.

Robot came to Dog with no history at all; all he knows of the world is what he learns at Dog’s hands (paws?) and through their experiences together. He’s a perfect mirror, and in that sense a harbinger of what our robots are becoming, and I don’t think it speaks entirely well of Dog that he can’t seem to find anyone else in this bustling city to connect with in the same way. But after Robot’s winter of torment, Rascal rebuilds him not from a mail-order kit but out of the pieces of his own life. That’s a metaphor for a deeper, more complex relationship, and a more mature humanity on Robot’s part. Rascal’s care transforms Robot and thereby makes Robot his not by reprogramming him but by endowing him with capabilities that Robot could just as well use to express his love for Dog as for Rascal.

That gift of capacity—literally to make his own music and implicitly to love whom he chooses—is what makes Robot truly wild, and truly adult too. I’m a mysterian when it comes to the so-called hard problem of consciousness, so I doubt our actual robots will ever present us with the problem of their own emotional maturation. But for our own sakes, we could learn something from this dream of mature robot love.