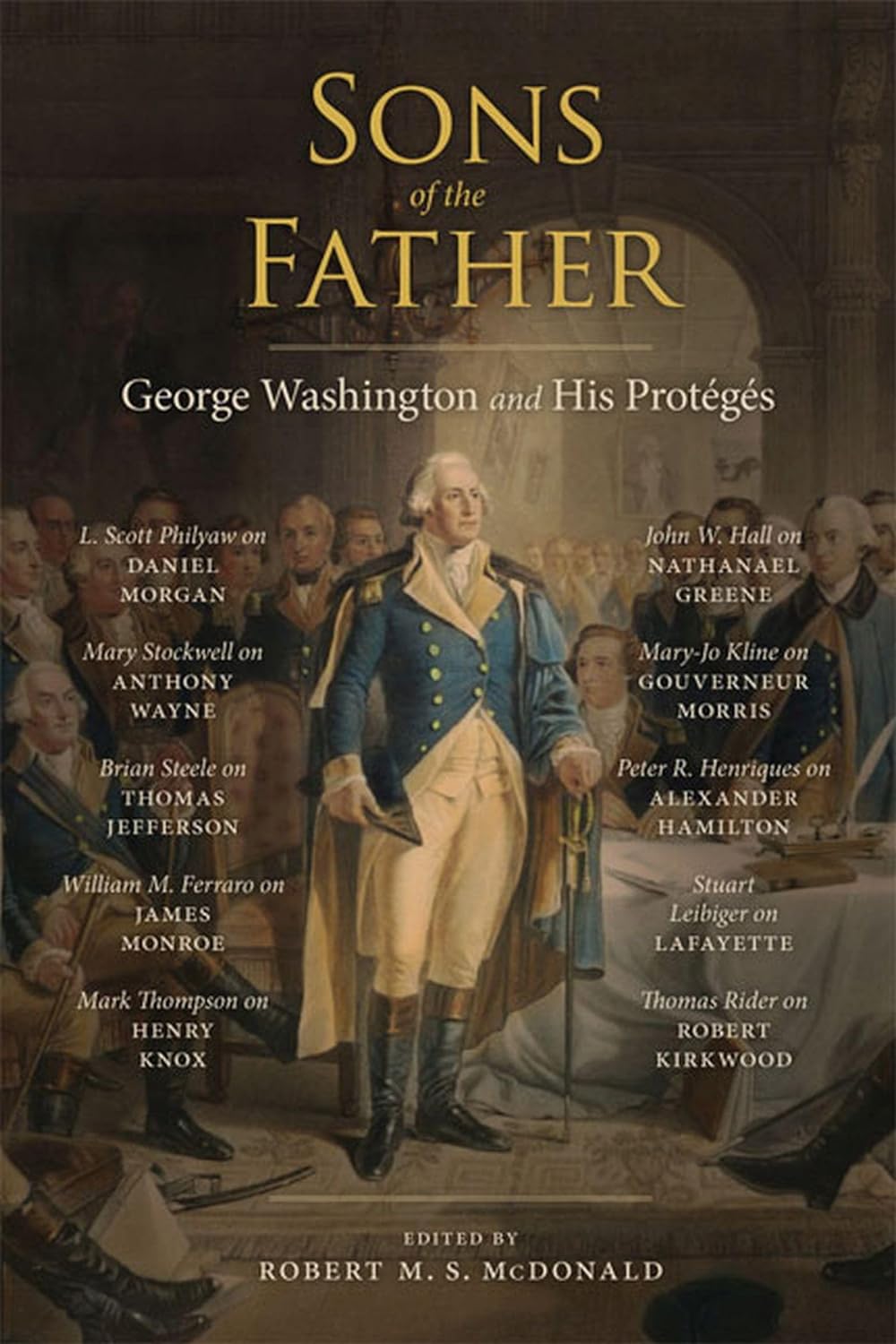

Given the sheer number of biographies and histories of George Washington and his times—including several excellent examples penned in recent years—the reader can be forgiven for wondering why this crowded field needs to be supplemented by an edited volume. The answer is simple: this book, with no fewer than thirteen contributors, in addition to editor Robert M. S. McDonald, manages to paint a surprisingly coherent portrait of our first president, and it’s one we haven’t seen before. As the editor notes in his preface, the contributors consider the lives, careers, and characters of younger men whom Washington influenced. The book is therefore a running, if indirect, commentary on the life, career, and character of Washington himself.

The men portrayed range from the famous—among them Gouverneur Morris and the Marquis de Lafayette—to the obscure, including the likes of Captain Robert Kirkwood. If Americans are really to understand Washington as a model of human excellence—as patriots of various stripes have been wont to do for centuries—it’s worth their while to read a series of case studies that dilate on the contemporaneous perceptions, and results, of Washington’s example. Or, as McDonald wisely puts it, “Understanding the full range of Washington’s leadership, which embraced all shades of persuasion and coercion as well as multiple modes of command and solicitude, requires the examination of his relationships with a particularly broad cast of characters.” These examinations are mostly convincing, although they do occasionally lapse into armchair psychology, leaving the reader the difficult task of determining just what lessons in statesmanship they teach.

Before getting to its central theme, the volume opens with a chapter by Fred Anderson on Washington’s mentors. Anderson offers some insight into the patron-client politics of colonial Virginia, through which social mobility was achieved and managed, and dangerous ambition curtailed in the face of weak governing institutions. Through patronage connections, including to the influential Fairfax family, the fatherless Washington was known to Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie before the two met at the end of Washington’s teen years. In short order, Washington was appointed emissary to the increasingly threatening French, and from thence quickly rose to colonel of the Virginia Regiment charged with defending the colony’s frontier.

An ambitious man like Washington was making his way, but he was doing so within the confines of a system that frustrated him. Those frustrations manifested in displays of “pride and imperfect control of temper” that resulted in a falling out with Dinwiddie. Anderson is perhaps too quick to dismiss the merits of Washington’s complaints, instead attributing them to the lack of a father to educate him in the art of deference. Yet he does note that the rigors of war developed skills and habits of self-control that would serve Washington well in later years.

L. Scott Philyaw offers the first chapter wherein Washington is the senior partner, detailing his relationship with Revolutionary War commander Daniel Morgan, a Virginian only a few years Washington’s junior. Morgan shared with Washington a commitment to independence and a nascent American patriotism forged out of common experiences in the Continental Army. Loyal to Washington despite perceived slights, Morgan enjoyed a long if not particularly close relationship with the commander in chief. Washington’s eventual appointment of Morgan to lead the occupation of Pittsburgh in the aftermath of the Whiskey Rebellion—because he was the best man for the job—illustrates the ascendancy of the Revolutionary idea of merit over the colonial idea of deference.

Similarly, Mary Stockwell’s treatment of Pennsylvanian general Anthony Wayne’s relationship with Washington suggests that loyalty and patriotism on the part of Wayne could and did overcome personal misunderstandings on the part of Washington. It was a patriotism that would eventually cost Wayne his life in service to his country. The book makes clear that, in America, ideas of merit and honor rose to the occasion the founding times demanded, and the high regularly triumphed over the low.

And as Brian Steele shows in the third chapter, even Jefferson, despite his many suspicions of the nation’s tendencies from at least the second Washington administration, did what he could to separate the Father of His Country from lesser men—the Federalists who tried to claim his legacy. “Because he remained aware of Washington’s value as a national icon, Jefferson was already, by 1800, beginning the process of transforming Washington from the partisan he had become late in life.” But this was not simply a matter of utility. Despite personal alienation, Jefferson genuinely believed Washington was willing to give republicanism a fair trial and would sacrifice his blood in support of it. Rescuing Washington from partisanship was part of the Jeffersonian effort to preserve the republic.

William M. Ferraro also makes plain that James Monroe, too, had what might be called an on-again-off-again relationship with Washington; yet in the end the ordinary vicissitudes of human affairs were always resolved in Washington’s favor. As his death approached in 1831, Monroe saw Washington as he had early in his life—a noble role model deserving of a “reverential tone.” That Americans were all republicans, all federalists—at least in their understanding of George Washington—was borne out by both Jefferson and Monroe.

* * *

Washington could spot talent and was willing to take risks in promoting those who had it, a fact illustrated by his relationships with Henry Knox and Nathanael Greene, according to Mark Thompson and John W. Hall, respectively. On Washington’s recommendation, Knox became America’s youngest major general, putting his considerable book learning together with remarkable energy on the battlefields of the Revolutionary War, and as Washington’s first secretary of war. Greene, like Knox, rose rapidly to become one of Washington’s most trusted military subordinates. Despite various personal stresses and strains associated with extraordinarily trying circumstances, both Knox and Greene remained loyal friends of Washington’s until his death.

And indeed, Washington was capable of lasting friendship even with the cosmopolitan Gouverneur Morris, a man twenty years his junior with no military background and who sported something close to the opposite of Washington’s reserved behavior. Mary-Jo Kline is perhaps a tad reductionist in seeking commonalities in their childhoods, but she does allow that the two men shared common views of important public questions, as well as a mutual regard for each other’s merits. As Morris wrote to Washington in 1793: “Happy Happy America governd by Reason, by Law, by the Man whom she loves, whom she almost adores. It is the pride of my Life to consider that Man as my Friend and I hope long to be honor’d with that Title.”

Alexander Hamilton, by contrast, expressed less fulsome affection, instead cultivating his connection to Washington in service of his own ambition, according to Peter R. Henriques. In spite of this—not to mention his having enemies across the political spectrum, for both personal and political reasons—Hamilton became Washington’s most influential adviser. One of America’s great public documents—Washington’s Farewell Address—was a product of their close cooperation. The desire for glory united them at various stages of their lives and careers, both military and political, and Washington remained a genuine friend in spite of scandal. The desire for glory, on the part of both men, was rarely distinct from their patriotism, and Hamilton was gifted with unique knowledge, abilities, and qualities of character that served the new nation well.

According to Stuart Leibiger, the Marquis de Lafayette’s relationship with Washington also married convenience with friendship and mutual respect. Washington always had a way of commanding that. Even a relatively minor figure like Captain Robert Kirkwood of Delaware illustrates Washington’s power to affect others. As Thomas Rider argues, the junior officer, who participated in so many of Washington’s Revolutionary battles, fully imbibed the model of military virtues Washington provided, as did tens of thousands of others.

While Washington often comes across as human (all too human) in these studies, the overwhelming impression the reader takes away is of a patriot firm in resolve, consistent in principle, and prudent in action. Our first president betrays an ambition to found not a nation of desiccated Lockean individualism but instead a republic of virtue. As the editor notes, “George Washington fathered no children, but he never lacked for sons. . . . Nearly all of these ‘protégés’ at one point or another professed a level of respect for Washington that bordered on reverence, or even love.” On a more practical level, the book provides insight into Washington’s capacity for “management, motivation, control, and cultivation of talent.” As such, it can be read profitably not only by historians and political scientists with an interest in the American founding era but also by those with an interest in the various forms of “leadership studies” now so prevalent in American higher education.

In an afterword to the volume, Jack P. Greene offers some reflections on how a group of relatively underdeveloped colonies came to find leaders of the stature of Washington and his protégés. Indeed, the caliber of leadership that sprang up in the America of the 1760s surprised the British, and their underestimation of the possibility of such a thing was a “fatal and massive miscalculation.” According to Greene, the colonies from the early 1700s onward were accumulating large stores of human, social, cultural, and political capital that provided fertile ground for the creation and exercise of individual talent. But there was a bit more to it than that: some combination of extraordinarily good fortune and divine providence.

In his History of the American People, British historian Paul Johnson uses characteristically colorful language to get things about right, when he compares the leadership of the day on each side of the Atlantic. In England, we see historical “nonentities” and “boobies.” Yet he surmises that this fact might not have made much difference if

the men they faced across the Atlantic had been of ordinary stature, of average competence and character. Unfortunately for Britain—and fortunately for America—the generation that emerged to lead the colonies into independence was one of the most remarkable group of men in history—sensible, broad-minded, courageous, usually well educated, gifted in a variety of ways, mature, and long-sighted, sometimes lit by flashes of genius. . . . And what was particularly providential was the way in which their strengths and weaknesses compensated each other, so that the group as a whole was infinitely more formidable than the sum of its parts. They were the Enlightenment made flesh, but an Enlightenment shorn of its vitiating French intellectual weaknesses of dogmatism, anticlericalism, moral chaos, and an excessive trust in logic, and buttressed by the English virtues of pragmatism, fair-mindedness, and honorable loyalty to each other. Moreover, behind this front rank was a second, and indeed a third, of solid, sensible, able men.

And of this group, Washington was indeed first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.

Bradley C. S. Watson is author or editor of many books, including Living Constitution, Dying Faith: Progressivism and the New Science of Jurisprudence (ISI Books).