Louis Menand’s The Free World is by turns fascinating and illuminating but also frustrating and nebulous. It describes with vigor and verve some of the most important intellectual, artistic, and cultural trends of the last half of the twentieth century during one of the most consequential periods in America’s rise to global preeminence. It is an intellectual history of the Cold War told through ideas manifest in books, art, popular culture, and philosophy.

Menand is candid in admitting that the book “reflects the period it covers.” This period, as he amply documents, is incredibly complex. That’s in one sense reality, of course: as William James calls it “one great blooming, buzzing confusion.”

But I think we can do more to make sense of this period than Menand does. His “literary approach” never goes beyond description or chronicle to actually explain whether the trends he describes were the causes of, consequences of, or merely coincidental with the Cold War. Menand makes the case that they took place “in” the Cold War but not how, or to what extent, they were actually “of” it.

Some readers may not care whether Menand establishes any precise causal link between the Cold War and these turbulent cultural currents. After all, the mere chronicle of this “exceptionally rapid and exciting period of cultural change” might be seen as sufficient for sheer epic scope. The story of late-twentieth-century American arts and culture, very broadly defined, takes up over eight hundred pages (inclusive of copious notes), and just having that account in a single volume is quite an accomplishment for one person and is useful for the rest of us

The Free World moves from international relations theory and practice to postwar continental philosophy, modern art, social science, classical music and dance, rock ’n’ roll, civil rights, mass culture, counterculture, women’s liberation, higher education, and cinema, culminating with Vietnam and the collapse of America’s effort to win the Cold War not only with bayonets but also with the pen, the baton, and the artist’s brush.

In less steady hands, such a capacious intellectual canvas could quickly become a muddle, the intellectual equivalent of a book written by Jackson Pollock in his famous drip period. But Menand successfully weaves together these seemingly disparate events and characters. One particularly effective stylistic turn in this book is to connect otherwise distinct sections of each chapter with an individual or a concept from the last paragraph of the previous section. What makes this approach so effective is that it manages to join otherwise apparently unconnected sections with a surprising thread of common individuals or ideas.

To be sure, in some instances, Menand suggests a clear link between the Cold War and his history of ideas. For example, Menand connects the final resolution of the “German problem” of post–World War II Europe to changes in philosophy and music. “The example of Heidegger showed,” in his view, “how tricky it was to disentangle German philosophy from Nazism. And the case of music was, if anything, worse, since many distinguished German composers, conductors, and performers flourished under Hitler.” But, as Menand recounts, the composer John Cage dissonantly argued in a 1958 lecture that the United States could solve the German problem precisely because it rejected “tradition,” thus ensuring it was three Reichs and they’re out.

It remains unclear in Menand’s account, though, whether Americanism or something else actually triumphed. In his retelling of the controversy over the 1964 Venice Biennale Grand Prize for painting being awarded to Robert Rauschenberg, he wonders whether it “was really an admission of surrender—not to the Americanization of art but to the internationalization of art.” Subsequently Menand notes “the final irony of the whole American cultural diplomacy effort after 1945 … that what the CIA, the State Department, the museums, and the foundation tried to do—sell American art and ideas to other countries—was accomplished by other means and with little state involvement.”

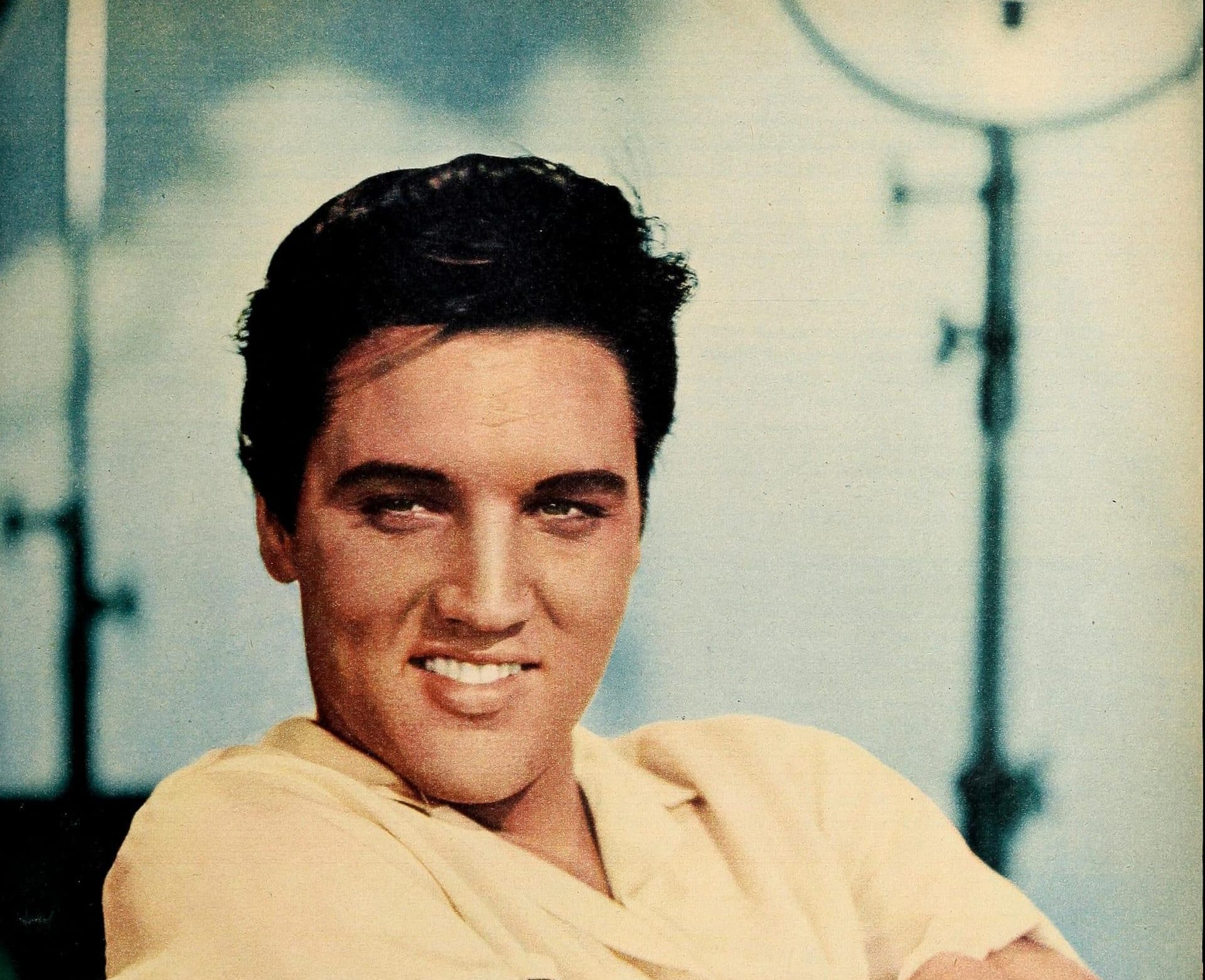

He hints that Americanism and internationalism had become largely synonymous. Menand’s fascinating discussion of rock ’n’ roll music illustrates how it survived to become, in his words, one of “the cultural winners of the postwar era.” It did so by doing the “extra-cultural work” of explaining postwar American social history, told mainly through the story of American youth culture. Through rock music, American youth culture would come to define and dominate global youth culture.

And in his important chapter on the growth of higher education in postwar America, Menand directly ties its second period of dramatic expansion (the first followed the Morrill Act from 1880 to 1920) to the exigencies of the Cold War. The GI Bill, the federal expansion of science’s “endless frontier” conceived by Truman’s science advisor Vannevar Bush, and especially the post-Sputnik National Defense Education Act of 1958 were all legacies of the previous war or preparations for the next one.

This expansion of the Cold War Beltway into the ivory tower had profound effects on American intellectual culture. In Menand’s view, “everything that got taken up into the academy ended up adopting a single discourse: the discourse of disinterestedness.” Paradoxically, the professionalization of American academia would be compatible not only with efforts to promote a “human science” approach epitomized by modern economics and its imitators in the rest of the social sciences but also with its polar opposite in the humanities, deconstructionism, which rejected any notion of objectivity.

The problem with being such a good writer and having such a broad cultural sweep is that Menand can conceal under his smooth prose and plush history some analytical fuzziness. There are two related issues here: First, was it really the Cold War or were there other developments (such as the Second World War or secular domestic changes) that affected the many important trends that pass under Menand’s magnifying glass? Second, when the Cold War was implicated in them, was it cause or effect?

On the former, Menand holds the Cold War responsible for the “enormous change in America’s relations with the rest of the world.” But while many of these momentous cultural changes had their effect during the Cold War—especially in philosophy and the arts—they were in fact the result of the rise of Hitler and the coming of the Second World War, which drove many leading European thinkers and artists (mostly Jewish) to the New World. In other words, they occurred before the Cold War. Recall that it was the Second World War, in which the United States not only won but did so without suffering large numbers of casualties (proportional to other nations) or any major damage to its industry or economy, that set up the U.S. for Cold War prosperity and global leadership.

Moreover, as Menand notes, “the existence of the Cold War was a constant,” but in his account it had varied effects across the many different intellectual currents in the wide river of the Cold War. You cannot use a constant to explain a variable. Relatedly, Menand claims that “the artistic and intellectual culture that emerged in the United States after the Second World War was not an American product. It was a product of the Free World.” But what was the “Free World” if not the Pax Americana?

Menand makes a compelling case that Cold War concerns—how can we champion non-whites in the developing world as part of our Cold War rivalry with communism when we have segregation at home?—added fuel to the civil rights revolution. But his effort to make a similar move to explain women’s liberation falls flat. It was, once again, the Second World War that opened kitchen doors and freed the distaff side from domestic bondage; but the Cold War was different in that its smaller manpower requirements and its limning by a small coven (mostly male) of nuclear Wizards of Armageddon meant that it could be kept from going hot without mobilizing half of the population.

An important subtext in Menand’s book is that the period from the end of the Second World War through the Vietnam War was eroded by an undercurrent of introspection about American liberalism, which was the political, economic, and social software that ran our domestic system and large parts of the global order. Not only did it produce unparalleled freedom and prosperity at home and abroad, it also discomfited some thoughtful Americans.

His discussion of American diplomat George F. Kennan and his post–World War II realist fellow travelers makes clear how America’s dominant and domineering liberal culture sat ill at ease with the Old World, nineteenth-century views of these realpolitikers. Kennan and his ilk not only rejected the Cold War as an international crusade of good (us liberals) versus evil (them commies) but also harbored deep skepticism about the virtues of “Americanization” of the postwar world, which connected our domestic politics with our foreign affairs.

More comfortable in a bygone age peopled by Castlereagh, Metternich, and Bismarck, American realists like Kennan saw containment as “a middle path, a way to be anti-Communist without going to war.” The balance of power was realism’s theory of peace, a view most Americans then and since have unfortunately not found congenial. Realists such as Kennan worried that liberalism was antithetical to the realism that ought to guide the West through the treacherous shoals of the long struggle with the Soviet Union.

Others were more preoccupied with domestic pathologies, especially the paradox Menand highlights “that the American political system was a protector of liberty, but that American society was a dangerous realm of conformity.” But there are two very different ways of analyzing America’s liberal tradition, each of which has very different strengths and weaknesses.

Menand himself attributes his literary approach, which many associate with Columbia University professor and social critic Lionel Trilling, to Commentary editor Elliot Cohen, whose “mind was dominated by his sense of the subtle interrelations that exist between the seemingly disparate parts of culture, and between the commonplaces of daily life and the most highly developed works of the human mind.” This constitutes Menand’s preferred method.

For Cohen, Trilling, and Menand, literature provides the best means of seeing limitations of American liberalism. Politics, in their view, is complex and often irrational, something that a literary sensibility both recognizes and understands. But like liberalism, the literary approach has both strengths and weaknesses, many of which are evident in Menand’s account of the social history of the Cold War.

There is another way of understanding American liberalism. I would characterize it as the historical/philosophical approach, which emerged around the same time in the early Cold War. Its foremost proponent was the Harvard University government professor Louis Hartz, who famously argued in his book The Liberal Tradition in America that American liberalism, which he associated most closely with John Locke, “contains a deep and tyrannical compulsion,” or what David Hume characterized as an “imprudent vehemence,” to remake society and the world in its own image.

In Hartz’s telling, American liberalism developed in a political environment where it faced no serious ideological alternatives. In contrast to Europe, where liberalism had to contend with feudalism and conservative political, social, and economic orders, American liberalism faced few such serious alternatives—the Puritan Northeast vanished, and the quasi-feudal South was crushed. The result was a liberalism that regarded its premises as self-evident and anyone who did not share them as defective at best and dangerous at worst.

Compared with the literary approach, Hartz’s historical and philosophical approach is clearer about cause and effect and offers, at least to my mind, a more satisfying account not only of the peculiar dynamics of American Cold War domestic politics—in which, for example, Wisconsin could send ultra-anticommunist Joseph McCarthy to the Senate while electing a Socialist mayor of its largest city—but also its behavior abroad.

Three fine illustrations of how this approach illuminates aspects of the Cold War period include Samuel Huntington’s magisterial The Soldier and the State, which uses Hartz to great effect to connect domestic and international politics; Huntington’s American Politics: The Promise of Disharmony, which updates Hartz on the recurrent tumult of American democracy; and Robert Packenham’s Liberal America and the Third World, which dissects U.S. interventions in the Third World through a Hartzian lens.

Imagine the fascinating patterns we would find if we looked at the rich tapestry of Menand’s account of the Cold War through a more disciplined and systematic lens like this.

Michael C. Desch is Packey J. Dee Professor of International Relations and Brian and Jeannelle Brady Family Director of the Notre Dame International Security Center.