All politics is virtue politics. The Founders understood this and thought that their new government would require virtue. They disagreed about where this might come from, however. The most obvious place would be from the voters themselves, animated by a bottom-up sense of fraternity and solidarity, like that portrayed in Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico by Ambrogio Lorenzetti in his Allegory of Good Government (1339).

During the Late Middle Ages, Siena and Tuscany had become the wealthiest and most highly urbanized regions in Europe. While Siena owed formal allegiance to the Holy Roman emperor, it was effectively a self-governing republic, a city of merchants, and more democratic than America at its founding. It was at peace, prosperous, and happy, and its council commissioned an artist to tell its story. The artist was Lorenzetti, and what he produced was a brilliant analysis of what makes for good government.

In one panel, set above the door to the council chamber, Lorenzetti showed how Siena had become so successful. On the left, Justice looks reverently upward to the figure of Divine Wisdom and on either side holds a balance from which angels dispense distributive and corrective justice. Below them, a cord descends to the figure of Concord, which binds the Sienese together as common citizens. Concord bears a heavy carpenter’s plane, symbolizing equality, and levels society so that no one person stands above anyone else. The cord then passes to a group of twenty-four citizens who symbolize the city councilors, each one of whom hands it to the person in front of him. Crucially, they hold it and aren’t held by it, since everyone is asked to take an active role in maintaining justice.

From the councilors, the cord passes upward to a regal figure who personifies the common good. He is surrounded by civic virtues represented by six female figures: Fortitude, Prudence, Temperance, Justice, Magnanimity, and a reclining figure of Peace. Above them hover the Church’s theological virtues of Faith, Hope, and Charity.

Lorenzetti’s allegory conveys the idea that virtuous government produces peace, order, and good government, but what is equally important is how this comes about. The cord runs from Justice through the popolo, who have been made equal by Concord, and from them to the city government or Commune.

The direction is bottom-up, and not top-down from the Commune to the people. The common good emerges from the citizens and their representatives, informed by a divinely inspired sense of justice. When republics fall, it is from their selfishness and vice, as described in a companion Lorenzetti fresco, The City State Under Tyranny, where “no one is ever in accord with the Common Good.”

The idea of popular virtue has always resonated with Americans. We tend to believe that the voters are pure and that our political ills can be traced to officials who fail to represent their constituents’ interests. That was the message of Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939). The guileless Mr. Smith (Jimmy Stewart) is appointed to the Senate, and when he inadvertently gets in the way of a self-dealing political boss is framed for corruption. It looks as if he’s lost, but then he draws strength from a visit to the Lincoln Memorial and filibusters his way to redemption. The film’s message is that, however corrupt things are, they can always be made right by someone “with a little, plain, decent, uncompromising rightness.”

Capra’s film portrayed the virtue of the many. Alternatively, civic virtue might be imposed from above by virtuous officials. That’s the virtue of the few, and it’s what most of the Constitution’s Framers thought would be needed. They didn’t put much faith in the many. As Horace White observed, they took their religion from Calvin and their theories of government from Thomas Hobbes. The mobs were all very well during the revolt against the British, but not after they threatened the new state governments.

If the many were less than virtuous, that wouldn’t matter, however. Virtue would be provided by the few through a system of filtration. Low-information and self-interested voters would choose more virtuous representatives, and they would elect a yet more virtuous president. In that way, cream would rise to the top.

There has always been a debate over the competing claims of the few and the many. Today, those who prefer the few comprise a Court Party and think that good government requires the guidance of a superior class that rises above the mistaken and vicious beliefs of the deplorables. Its members are composed of the pooh-bahs in our universities, the legacy media, and Wall Street. They know how to spend other people’s money, fix the weather, and address the root causes of crime.

They tell us that the people who objected to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic should have deferred to the experts at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And if the masses object? Why, they’re low-information voters who hearken to the dog whistles of racist demagogues.

Against this class of privileged insiders, the Trump voters making up a Country Party condemn the Court Party as a self interested aristocracy that is not above using the court system to silence its opponents.

The distinction between the two sources of virtue arose in early eighteenth-century British politics, was seen again at our Founding, and explains today’s political divisions.

Walking into the Constitutional Convention, James Madison strongly supported the virtue of the few and the idea of “filtration.” In the Virginia Plan he supported, this would have meant, among other things, that senators would be chosen by the House of Representatives, and both houses would elect the president. After the Connecticut Compromise, however, Madison gave up his grand design. There would still be filtration, but now the states would be doing the filtering, and as a strong nationalist Madison hated this idea.

The man whom conservatives call the Father of the Constitution seems to have proposed a walkout, which likely would have split up the country. The Convention was rescued by more clever people, notably Gouverneur Morris, who gave us the Constitution’s Article II on how to choose a president.

Madison had lost, and he knew it. Nevertheless, in the Federalist he argued that, with the separation of powers, the country could do without either virtuous voters or virtuous officials. Everyone would be self-interested, but in the competition for power they’d cancel each other out. Ambition would check ambition.

It’s not a daft theory, and I am sure that on balance it did more good than harm—as Professor McTaggart once said of God. But it obviously hasn’t sufficed. The lobbyists of K Street, the trade associations ensconced in Alexandria, and vast networks of political donors have created what the historian J. G. A. Pocock called “the greatest empire of patronage and influence the world has known.” Our government is “dedicated to the principle that politics cannot work unless politicians do things for their friends and their friends know where to find them.”

What Madison had failed to recognize is that self-interested politicians are savvy enough to bargain with each other and that wheels will be greased through vote-trading and logrolling. Congressman A will trade off a steel tariff about which he doesn’t care in favor of milk subsidies that do matter to his voters with a Congressman B who has the opposite preferences. The first politician achieves his principal objective while surrendering something about which he cares less, but about which the second cares more strongly. They both win, even if the common good loses.

Madison has a twenty-first-century heir in Yuval Levin, the director of social, cultural, and constitutional studies at the American Enterprise Institute and the author of the well-received new book American Covenant: How the Constitution Unified Our Nation— and Could Again. Levin seems to think that the common good will emerge out of horse trading. In the social science literature, that used to be called “pluralism,” but nobody believes in it anymore. It was the unofficial ideology of FDR’s Democratic party, which saw politics as a Madisonian competition for power amongst different and legitimate self-interested groups—labor unions and big business, Christians and Jews, farmers and suburban consumers. There was no one power elite but instead an array of varied groups, each clamoring for political gain. Each group would cut deals with all the other rival groups, and this would protect everyone.

The pluralists thought that republican virtue was a delusion and expected powerful groups to employ every bargaining edge possible to extract gains for themselves. And so Democratic pluralists turned a blind eye to Tammany Hall and corruption, as well as to unjust advantages like those of whites over blacks. After a time, the confused compromises became intolerable, and the Democrats moved on. As for the Republicans, they never believed in pluralism. The compromises produced by horse-trading were simply the kinds of corrupt bargains with which Harry Reid cobbled together Obamacare.

Levin is an intelligent observer of American politics who recognizes that the separation of powers isn’t James Russell Lowell’s machine that would go of itself. In American Covenant, Levin argues that, pace Madison, civic virtue still will be needed. By that he means a measure of self-doubt and a willingness to concede that compromise can produce a better result than simply having one’s own way.

Levin admires Benjamin Franklin’s wise advice on the last day of the Constitutional Convention. Franklin recalled how a French lady had said that, while she didn’t know how it happened, whenever she argued with someone it was always she who had had the right of it. Don’t be like that lady, Franklin told the delegates. You might not like everything in the Constitution, but vote for it anyway.

Franklin was right, but are we willing today to compromise with our ideological opponents? There are three reasons to think that we’re not and that the kind of virtue Levin prizes is a thing of the past.

First, we’ve discovered that hating our ideological enemies is just too much fun to give up. Read the bitter online comments on stories in the Washington Post and you’ll encounter lumpen nullities chasing their anger high. They could avoid this vexation by turning to the sports section, but instead they search for rage-inducing provocations to trigger the dopamine reward receptors in their brains. And like a pusher at the corner, the Post is happy to give them their fix. The paper should be delivered in a brown paper bag, like the smut magazines of the 1950s.

The second reason why compromise is impossible is because the bargaining zone is empty. No trades are possible when whatever one side wants would be entirely unacceptable to the other. Forty years ago, Ronald Reagan and Tip O’Neill could cut a deal over tax cuts. On fundamental matters the two were in accord. Today, however, the two parties quarrel about whether we need state aid for parochial schools or for transgender surgeries, things about which no compromise is possible.

The Trump voter’s deepest wish is to break up the monastery—to defund a corrupt system of higher education, enforce free-speech rights on social media, and rein in the undemocratic regulatory state. In return, he would be willing to offer the other side left-wing economic programs about which he cares less. That kind of a bargain might have been acceptable to an older Democratic Party that championed economic equality. Today it would be rejected by the progressives who make up the leadership of the Democratic Party, who care more about their elite issues than they do about economic matters.

So nothing gets done, and the people who are shortchanged are the median voters, the men in the middle. They’re social conservatives and slightly left-of-center on economic issues, and they decided the outcome of the 2016 election. They’re not right-wingers, and they’re not progressives either. If we really could have the kind of compromises that Levin wants, they’d call the shots. If they don’t, and we can’t get all the nice things they want, blame the Constitution.

The median voter is better represented in parliamentary systems that lack a separation of powers and in which the House of Commons is all-powerful. Those countries also rank higher on measures of political liberty and freedom from corruption than the unfortunate countries to which we exported our Constitution. The judgment of the world is that parliamentary constitutions are superior, and securus iudicat orbis terrarum.

We’ve remained free, but that is in spite of and not because of the Constitution. We remained free because, until now at least, we possessed something that didn’t travel along with the paper parchments we exported to presidential regimes such as those in Venezuela and Nicaragua. And that was civic virtue, the willingness to compromise that Levin rightly praises and that today is so lacking in our politics.

The third reason why compromise is impossible, however, is that under our presidential form of government we’ve found we can do without it. Levin assumes that with the separation of powers Democrats and Republicans must learn how to compromise. But the separation of powers is nullified when every important political decision is made from the White House and the president doesn’t have to bargain with anyone. Then the system is winner-take-all, which is how Democrats play the game.

This should not have been unexpected. A separation of powers is inherently unstable. Like wrestlers in a ring, the separate branches will contend for supremacy. In parliamentary systems that began with a separation of powers, the House of Commons ultimately became the dominant branch. In presidential systems, the executive branch emerged on top. That explains why presidential regimes have been found to be less free than parliamentary ones. A presidential system designed to prevent the accumulation of power in a single person perversely produces just that result.

Madison’s error was to think that ambition might counteract ambition indefinitely and that the different branches would always remain in equipoise. That was a conceit which Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. (the jurist’s father) satirized in his poem “The Deacon’s Masterpiece.” The deacon had thought that when a machine falls apart it’s because one piece wears out before the rest, but that if each part were as strong as every other a one-hoss shay (or carriage) would last forever. So he builds a shay on those principles, and as expected it endures year after year. It outlasts the successive deacons until exactly one hundred years to the day after it was built. A new deacon takes it out, but in the middle of his ride he finds himself sitting on a pile of sawdust:

You see, of course, if you’re not a dunce,

How it went to pieces all at once,—

All at once, and nothing first,—

Just as bubbles do when they burst.End of the wonderful one-hoss shay.

Logic is logic. That’s all I say.

The message of the poem (written three years before the Civil War) is that we shouldn’t expect things to last forever, neither shays nor balanced constitutions. Logic is all very well for brittle little theorists, but let’s pay attention to how the world works.

That was how the separation of powers collapsed in Britain. The balanced British constitution of King, House of Lords, and House of Commons seemed written in stone to most of the Framers of our Constitution, who thought they had mimicked it in the plan they devised. In 1787, the Westminster system required the assent of King, Lords, and Commons before a bill could be enacted, and this was more than a matter of mere formality. George III had been weakened by the loss of the colonies in the American Revolution but still retained important powers. The monarch’s veto had last been used in 1708, but George’s unwillingness to agree to Catholic emancipation brought down the ministry of Pitt the Younger in 1801. Through his power of patronage, the King could also rely on the support of the “King’s Friends” in the House of Commons, and while this smacked of corruption, David Hume defended it as necessary to ensure that the separation of powers survived.

Over the next fifty years, however, the King and House of Lords lost power to the House of Commons, and by the time of the 1832 Reform Bill the Commons had emerged as the dominant branch of government. A determined House of Commons could insist on getting its way and might require the King to appoint new peers to the House of Lords to overcome any objections from that body. Looking backward in 1867, Walter Bagehot, writing The English Constitution, saw clearly that the “efficient secret of the English Constitution may be described as the close union, the nearly complete fusion, of the executive and legislative powers.”

Beyond its human drama, the Netflix limited series The Crown was a graduate seminar on Bagehot’s constitution. The eighteenth-century constitution had been one of separation of powers, of checks and balances, which continued to describe what Bagehot called the “dignified” part of the constitution, the part in which the Queen was the head of state and the House of Lords shared legislative powers with the House of Commons. After the Reform Act, however, there was a chasm between the dignified part of the constitution and the “efficient” one, in which real power was located. The House of Commons was now all-powerful, and as it determined who would serve as prime minister and who might be appointed to the House of Lords, the legislative and executive branches of government now were merged in the lower house. The efficient secret of the English constitution was the abandonment of separationism.

All this was in the future when our Framers met in 1787. Of them, perhaps only Gouverneur Morris saw the shape of things to come. Over time, however, America came to resemble Britain with its distinction between a dignified and efficient constitution. In the dignified constitution, senators and representatives give speeches to which no one listens, and on occasion they enact laws which none of them have read. They’re required to pass spending bills to keep the government open, and this they always do. In the efficient constitution, however, real power resides in the executive branch.

The president of the United States has slipped off many of the constraints of the separation of powers. He makes and unmakes laws without the consent of Congress, spends trillions of government dollars, and the greatest of decisions, whether to commit his country to war, is made by him alone. His ability to reward friends and punish enemies exceeds anything seen in the past.

In periods of divided government, when Congress is in the hands of the other party, a president might in the exercise of an unfettered discretion refuse to enforce laws that were properly enacted. A notorious example is the Biden administration’s open-border policies, which showed a complete disregard for the president’s constitutional duty to “take care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” A president might also bypass Congress and adopt essentially legislative policies that trench on the Constitution’s allocation of legislative powers to Congress. In office, President Obama urged Congress to pass the Dream Act, which would have given conditional permanent residency to illegal immigrants. When Congress voted down the bill, Obama issued an executive order that the immigrants not be deported. The new program provided for a formalized procedure, called the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, which would allow an estimated 1.7 million young undocumented immigrants to live and work in the United States.

Obama had done more than decline to enforce the old law: by executive fiat he had replaced it with a new law. Then his Deferred Action on Parents of Americans program granted five million illegal aliens immunity from deportation and gave them work permits. It read like a statute, but it wasn’t one, and it wasn’t even a regulation or executive order. Instead, it was a memorandum from the secretary of the Department of Home land Security. As the Democratic advisor Paul Begala put it: “Stroke of the pen. Law of the land. Kind of cool.”

All of the features of the Constitution that Yuval Levin admires, the way in which things can’t happen unless the different branches are in accord, have merely served to shift power to the executive branch. Levin even likes the Senate filibuster, which makes it harder still to get anything passed. That means that people will have to compromise, he says. No, it doesn’t. It really amounts to a transfer of power from Congress to the presidency. It makes the president more powerful when something has got to give and only the president can make it happen.

We might not like where that leaves us. In the Constitutional Convention, George Mason warned that the president would become an “elective monarch,” with more legitimacy than that of an unelected king. Mason was right about that. Today, American presidents have more power than George III ever had. We are repeating British constitutional struggles between king and parliament in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, between Charles I and Cromwell, and this time the king is winning. When Democrats tell a president like Joe Biden to ignore Congress, they’re the new Tories.

People who used to be called Whigs, and who object to one-man rule and kingly government, will be troubled by this state of affairs. But it’s simply the logic of the structure of government. The American Constitution is a “prisoners’ dilemma” game in which joint cooperation means that both parties will play by the rules and not overstep the limits on presidential power. Defection means running the country from the White House as if Congress doesn’t exist. The problem is that, while joint cooperation produces the best overall result, joint defection is individually rational for both parties. That means an unbounded executive power, and in game theory it’s the solution of the game.

That won’t sit well with Whigs like Levin. They’ll observe Democrats playing outside of the lines but ask Republican presidents to refrain from doing so. So Democratic presidents get to do what they want, but Republican presidents don’t. Game theorists call that being a patsy.

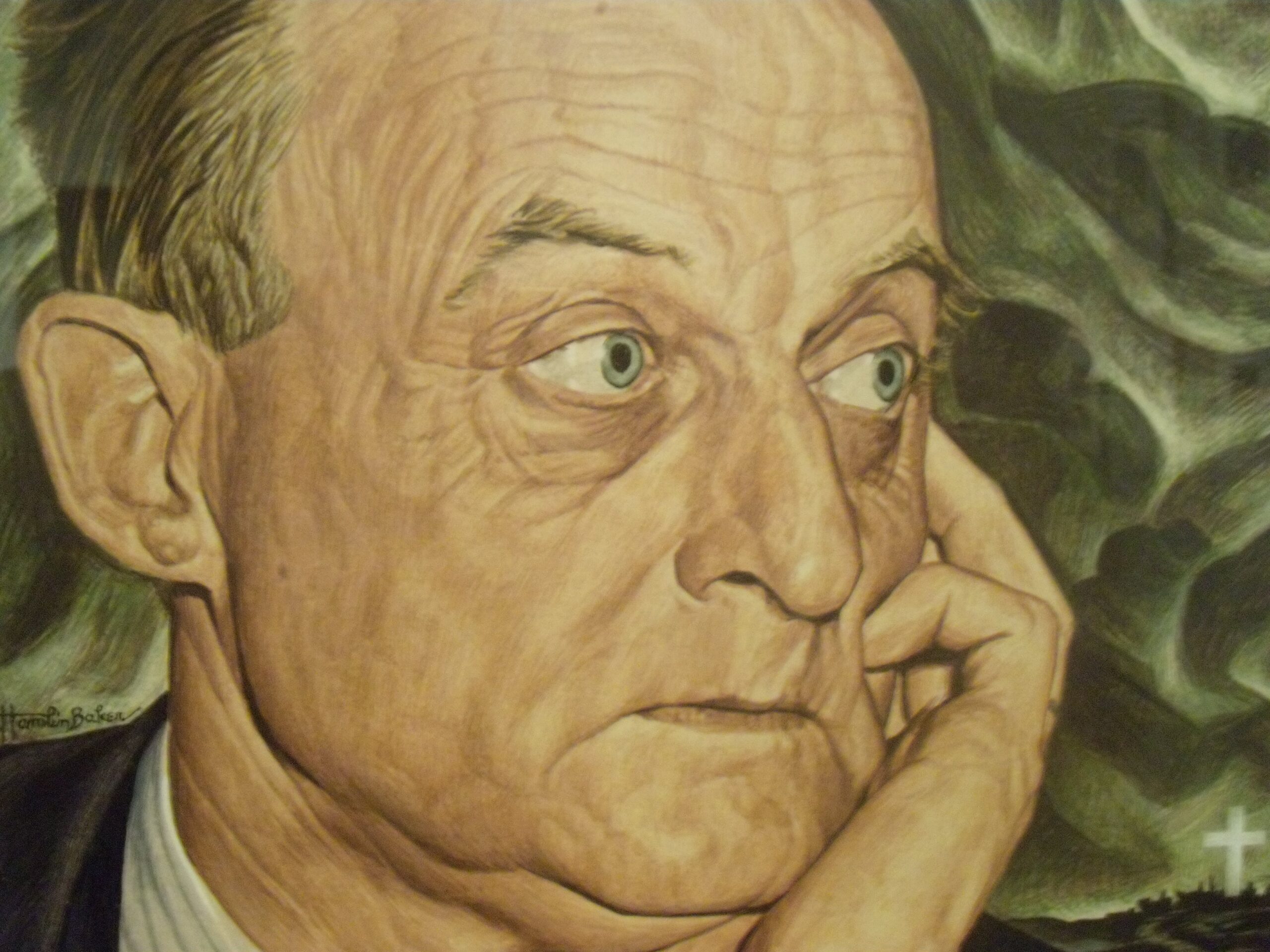

There’s another reason why power gravitates to the executive branch under the separation of powers. Congressmen have lousy incentives. They’ll want to favor their district at the expense of the entire country, as seen in the “Louisiana Purchase” and “Gator Aid” payoffs when Harry Reid had to scramble for votes to get Obamacare passed. By contrast, presidents are elected by the country as a whole, and their incentive is to promote the good of the entire country. They will naturally tend to become the kind of leader whom Viscount Bolingbroke proposed at a similar moment in British politics.

Speaking for a Country Party that opposed the Robert Walpole ministry’s corruption, Bolingbroke in 1740 argued for the return of political virtue through a “Patriot King” who would seek the common good. Today the logic of American government points to a similar solution, with a Patriot President who alone defends the common good against self-interested factions and interest groups.

The Democratic party’s constitutional principles can be summarized as “by any means necessary,” and a Trump-led Republican party seems poised to join them in embracing winner-take-all presidential politics. The problem begins to look irreversible, and Bolingbroke’s Idea of a Patriot King has become essential reading for anyone who seeks to understand American politics.

Patriot Kings and Patriot Presidents present their own dangers, however, and a constitution meant to preserve political freedom might in the end weaken it. The separation of powers has served to create a system of strong presidentialism that in other countries has led to one-person rule. That hasn’t happened here, but if Levin thought that civic virtue would protect us, the wellsprings seem to have run dry.

Of course, that doesn’t necessarily mean that we’re about to become another Venezuela. The Supreme Court constrains executive overreach and was quick to do so when Trump took office in 2017. Of a Supreme Court that might be appointed by Kamala Harris and face a Democratic president, however, I am more far more skeptical. But it is foolish to try to predict the future.