What do you do when your political champion, Barry Goldwater, is trounced in a presidential election, winning only 38.5 percent of the popular vote, and the media proclaim that his ideas are irrelevant and the movement he headed is dead?

Do you take early retirement from the political wars? Seek encouragement from Frank Meyer, senior editor of National Review, who pointed out that despite the unrelenting campaign to make conservatism seem “extremist, radical, nihilist, anarchic,” two-fifths of Americans still voted for Barry Goldwater for president in 1964? You can build a formidable political movement with a base of 27 million voters, Meyer said.

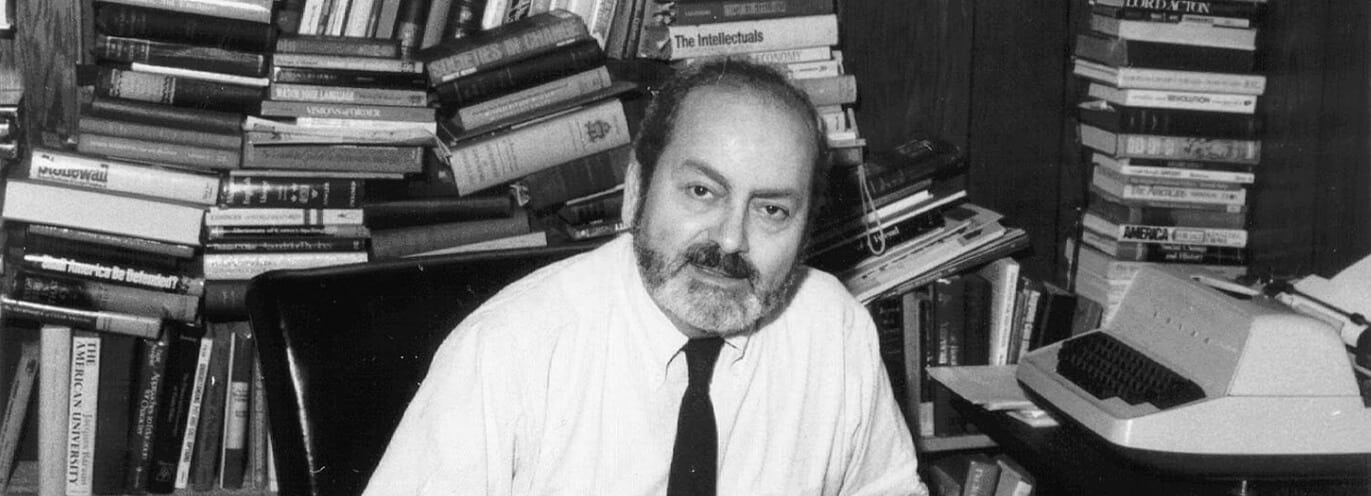

From his Philadelphia office, midway between the political enclaves of New York City and Washington, D.C., Vic Milione, president of the Intercollegiate Studies Institute (ISI), was not downcast by the electoral results. The critical thing, he said, was to assert the importance of education, not politics, “in shaping the course of future events.” Ideas have consequences, Milione said, and in the long run conservative ideas will prevail. He was right: just sixteen years later, conservative Ronald Reagan was elected president of the United States in a landslide.

The Sixties were a major test of ISI’s long-range “educating for liberty” strategy. Radical students chose the University of California, Berkeley as their first major battleground. In September 1964, returning students encountered an impassioned “Letter to Undergraduates” that urged them to “organize and split this campus wide open!” The conflict climaxed in early December with a giant nighttime rally and sit-in at the administration building. Police were called in to clear the hall, and 773 young people were arrested, radicalizing the campus. The Free Speech Movement morphed into the Filthy Speech Movement, a loose alliance of radical students, hippies, and street people who kept alive the spirit of protest at UC Berkeley for the rest of the decade.

Student activism across the country was reinforced when President Lyndon B. Johnson sent the first contingent of American ground troops to Vietnam (they totaled 184,314 by the end of 1965) and his administration began using the draft for manpower. Campus demonstrations against the war surged. The mid-1960s also marked the birth of the counterculture, which rejected traditional American values such as faith, family, and work. The counterculture championed sexual experimentation and instant gratification, leading young people by the thousands to, in the words of Timothy Leary, turn on, turn in, and drop out.

Just as Vic Milione had anticipated Goldwater’s defeat because of the political forces arrayed against him, so too was he prepared for the campus chaos of the Sixties through his deep reading of historians like Hermann Rauschning and Jacob Burckhardt. A “great crisis,” wrote Rauschning, is marked by “the breakdown of the intellectual and ethical norms, of the ideas and principles, of the creeds and ideals which comprise the content of a civilization.”

As disturbing as the breakdown was, the proper response, Milione insisted, was to concentrate on the root causes and offer root solutions. “If you want to win in the current conflict,” he wrote an ISI trustee, “you get the best minds possible . . . into contact with the best students possible.” That had been and would continue to be ISI’s mission, he declared, even if an intellectual approach lacked sufficient “sex appeal” for some conservatives. Considering the stakes, Milione said, “it would be disastrous to sacrifice substance for sex appeal.”

ISI lecturers calmly challenged the radicals. Professor Lewis Feuer, who had taught at the University of California, Berkeley and publicly debated Free Speech founder Mario Savio, said that the New Leftists “were possessed by a terrible, compulsive irrationality which corrupted their idealism.” He argued that the modern intellectual should turn to Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, who tested their ideas by action and were prepared to answer for their actions. “This,” said Feuer, “is the tradition we must try to recapture by working through American democratic institutions.”

ISI set about expanding its reach on the campus and beyond. In 1968, the institute distributed more than 300,000 pieces of literature, assisted campus representatives at 190 schools, published three issues of its journal the Intercollegiate Review, and maintained a list of more than 30,000 members, including students and faculty. Milione was especially proud of what the Weaver Fellowship graduate program had accomplished in three short years.

Of the thirty fellows, one-fourth of them were already teaching full-time, and three-fourths were studying for an advanced degree. “Many graduates . . . would turn their backs on graduate education,” said Weaver Fellow John F. Lehman of the Foreign Policy Research Institute and later secretary of the Navy under President Reagan. They would have been “lost to the professions of teaching and research were it not for the Weaver program.”

ISI’s burgeoning activities elicited more student requests, producing a painful paradox. “The Institute,” reported National Director John Lulves, was not “able to service properly the minimum requests of students who came to ISI—to say nothing of the thousands yet to be approached.” Expenditures for 1968–69 doubled the ISI budget of six years earlier but were still less than what was needed to guide the young conservatives who believed, with Plato, that the purpose of education was to assist students in gaining wisdom and virtue.

Vic Milione responded calmly to the financial challenge, informing trustees that several major foundations had agreed to contribute to an “ISI Reserve Fund.” Neil McCaffrey of the Conservative Book Club was helping with a test mailing for a national direct-mail campaign. Through trustee and golden donor Henry Salvatori, Milione met with potential major donors on a California trip. As a result, ISI entered the 1970s “in a much healthier financial condition” than in recent years. But, Milione assured his board of trustees, “we do not intend to sit on our duffs.”

Unique indeed was the relationship between Milione, the student of political philosophy, and Salvatori, the master of business. In one letter, Milione offered reflections by William Penn on government—“As governments are made and moved by men, so by them they are ruined too. Therefore, governments depend upon men rather than men upon government”—and by Tocqueville on rekindling an essential virtue. The “impulse of patriotism which never abandons the human heart,” Tocqueville wrote, may be revived, for “every fresh generation is a new people.”

Responding to Salvatori’s concern that ISI might be “overextending itself,” Milione admitted that “ISI does operate close to the bone. . . . The fruits of its efforts are remote.” But there was a critical need to combat “the pernicious influence of relativism” through ISI publications like the Intercollegiate Review and the Political Science Reviewer and the Weaver Fellowships. As to what a university should be, Milione said that ISI ought to convey to students “a comprehensive and overarching view of life.” Most of modern education, he said, “is too fragmented and diffuse to serve this end.” He concluded by stating: “You may well say, ‘To hell with it, the issue is too involved.’ You may, but I hope not and think not. You are one of the most thoughtful men I know and the only one to whom I would hazard sending such a letter.”

The aged philanthropist responded by thanking “Vic” for providing “much food for my thoughts.” Their personal meetings in New York when the Californian came East on business, or in Los Angeles when the Philadelphian visited trustees and supporters in the West, cemented a friendship that explains the generous support that Salvatori gave ISI year in and year out. His support and his belief in ISI’s mission centered on the man who presided over the institute for thirty-five years.

Victor Milione was born in May 1924 in the Philadelphia suburb of Penfield to devout Roman Catholic parents. His father was a sculptor who loved to read, especially the classics. Vic went to public schools as a boy and then to West Catholic High School in Philadelphia. Following Pearl Harbor, he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps and wound up in Colorado. At the war’s end, he took advantage of the G.I. Bill and enrolled at St. Joseph’s College, graduating in 1950 with a BS in political science.

He encountered his first Keynesian professor at St. Joseph’s, who argued that while government could be small in the “pastoral” world of the eighteenth century when the United States was founded, a large government was now needed “to accommodate the changes” wrought by the Industrial Revolution. Whereupon Milione sought, but failed to find, material in the college library to “refute the ideas of centralized government.” Thus was planted a seed that would flower into the limited-government, free-enterprise philosophy of ISI.

Vic Milione was a conserver of classical education, a defender of ordered liberty, a realist and an idealist.

Following graduation, Milione considered studying law but, eager to preach the advantages of the free market, especially to young people, went to work for Americans for the Competitive Enterprise System (ACES), an educational organization supported by Philadelphia businessmen. He traveled throughout the Philadelphia area, mostly visiting high schools but also Rotary and other service clubs, even farmers’ groups. He initiated an economic-education program for plant employees to whom he explained the economic fundamentals of a free society, stressing that profits were not evil but good, because they led to jobs and prosperity.

At an ACES board meeting, Milione met Charles H. Hoeflich, a successful banker who became a lifelong friend and nearly permanent ISI secretary-treasurer. “It was always his brain,” said Hoeflich about Milione, “that fascinated me.” That brain was filled to the brim with the ideas of the great thinkers of Western civilization. In a single conversation, Milione would quote in extensio John Henry Newman, Alexis de Tocqueville, Seneca, Jacob Burckhardt, Ortega y Gasset, James Bryce, and Richard Weaver, his favorite twentieth-century conservative.

An ISI staffer once quipped, “Vic may not have been the most quoted conservative, but he was certainly the most quoting.”

Undeterred that ISI, then called the Intercollegiate Society of Individualists, had only $2,300 in its bank account, Milione signed on as its first and only campus organizer. Limiting himself to visiting schools in the East to save traveling expenses, ISI’s intrepid representative provided college students with the arguments that supported free-market economics, a respect for private property, and self-determination of the individual. It was these ideas, Milione said, that had motivated the Founders of the Republic, and “they must be part of the education of our young people.”

The young ISI organizer was constantly on the go, driving from campus to campus in a car filled with pamphlets and books, covering as much territory as possible as quickly as possible, conscious of the society’s scant funds. For example, his total expenses for two nights and three days in November 1953 were $54.97. On one trip he drove 395 miles at an estimated gasoline cost of $31.60.

Elected ISI president in 1962, following the resignation of the society’s founding president, the libertarian Frank Chodorov, Vic Milione led ISI in a new direction through the adoption of new bylaws. The “purposes” clause was amended to read:

The particular business and objects of [ISI] shall be to promote among college students, and the public generally, an understanding of an appreciation for the Constitution of the United States of America, the Bill of Rights, the limitations of the power of Government, the voluntary society, the free-market economy and the liberty of the individual.

The changes from the old bylaws were subtle but significant. Gone was any mention of “individualism”; added were references to “the voluntary society” and “the limitations of the power of government.” With this new clause, ISI ended its commitment to an individualism narrowly conceived and committed itself to a more humane understanding of man and society. No longer would there be a singular concern with “homo economicus,” but rather a broad examination of what constitutes the whole man, spiritual as well as economic.

Under Milione’s leadership, ISI forged enduring relationships with students, professors, trustees, and donors that enabled the institute to survive the revolutionary Sixties and attain significant influence in the Reagan years. Through the ups and downs, Vic Milione ensured that ISI stuck to its mission—“To Educate for Liberty”—a phrase Milione fashioned from the exhortation at the base of the Liberty Bell: “Proclaim Liberty throughout all the Land unto all the Inhabitants thereof” (Lev. 25:10). In the words of ISI executive vice president Jeff Nelson, Milione was “the animating soul of the intellectual movement for liberty on America’s college campuses.”

He built an independent network of students and professors. Through the Weaver Fellowship program, he financially supported generations of conservative teachers. He promoted the first principles of the Founding in the pages of the flagship publication, the Intercollegiate Review. He brought together future conservative leaders at summer schools and lectures. He supported a campus network of alternative student journals and newspapers. As Nelson wrote, Milione created the only institution that welcomed every strand of contemporary conservatism—libertarians, traditionalists, Straussians, Voegelians, Burkeans, anticommunists, communitarians, Protestants, Catholics, Jews, the secular—anyone and everyone who appreciated the signal importance of Western civilization and the American experiment.

Vic Milione was a conserver of classical education, a defender of ordered liberty, a realist and an idealist, who spread the word from campus to campus, community to community, person to person. His legacy is all around us in institutions like Thomas Aquinas College in California, the Claremont Institute, the Philadelphia Society, and the historic ISI campus in Wilmington, Delaware.

Laid to rest in 2008 at the age of eighty-four, Vic Milione may be an unsung hero to most Americans, but he and the institution he built inspired generations of conservatives to go forth and proclaim the blessings of liberty to all the inhabitants of this blessed land.