The issue today is between socialism and freedom.” Those who state their conviction in this way fear that the gradual expansion of government here at home will ultimately turn out to have been the road to communism. Is their fear well-founded? What precisely is socialism? Strictly speaking, the term connotes public ownership of the means of production. Today in the United States, socialism is a derisive name for any tendency of Washington to plan what must not be planned, to organize what should regulate itself, to regiment what ought to move in freedom. The fear of government invasion in certain areas of life bespeaks the premise that government has proper limits, that wide areas of human life should remain beyond its reach. We speak of a public and a private sphere. “Private” is not only the life of each individual person, and his relations with family and friends, but “private” designates also an entire system of social order in which not the government but the decisions of numberless individuals and their action upon each other keep house. The fear of “socialism” implies that this pattern of individual decisions constitutes a genuine order, an order that is valuable not only because it has intrinsic merit but also because its unhampered functioning guarantees the freedom of personal autonomy to all competent individuals who can exercise responsible self-control.

Public discussion of these problems is emotional and somewhat fuzzy. Clarity can be achieved only when one penetrates beyond the slogans to the underlying problems. The problems are institutional, but the institutional concepts are formed by theoretical premises. Thus when we speak of the limited state, which has been one of the perennial political problems of Western civilization, we must go further and examine the assumptions on which the notion of the limited state is founded. This takes us to the basic ideas about man, his ultimate destiny and his aspirations in life. The concept of man, in turn, inspires that of an order of life that lies beyond government action. In modern times, this idea has taken the form of a “natural order.” No more can be done here than roughly to indicate the direction of this kind of inquiry. Thus we shall explore the connection between the modern notion of the limited state and socialism, the difference between the welfare socialism of the Western variety and Marxist socialism, and the role which both socialisms play in the crisis of Western civilization. I shall try to show that socialism in the West, being a variety of liberalism, differs both in fundamental philosophies and policies from communism, but that both socialisms constitute relations between rulers and ruled that are alien to the spirit of freedom and friendship.

Aristotle said that the political community is the highest and most comprehensive of all communities. He argued that every community among men exists for a particular good, but the political community aims at the good of the whole life. Hence government, the art of politics, is the master art of them all, for it determines the respective importance and scope of all the other arts. There is nothing limited about this concept of the state. The limited state is a creation of Christian thinking, particularly of Augustine. It arose from the fundamental experience of the Incarnation, the appearance of God in human form at a definite place and time of human history. Christian thinking about politics was based on a new discovery about the destiny of man: man lived in order to attain fellowship with God. Augustine distinguished in this world two great communities among men: those who were drawn to each other by the common love of God, and those who understood each other in the similiarity of the love for themselves. The first he called the City of God. In its orientation toward eternal life, this community ranks highest among all human associations. Augustine, in other words, could not share Aristotle’s idea that the purely temporal institution of government represents the royal order, the master order. The City of God ranks higher. The state cannot be its master and director. Thus Augustine, for the first time in human history, assigned to the state a merely practical task of procuring a rudimentary sort of peace and a modicum of justice.

As a result, an entire sphere of human life, the spiritual sphere, was not only distinguished from the temporal order but deliberately put beyond the reach of the government. The spiritual and moral life of man, with its purpose of salvation, was left to the autonomous authority of the Church. The significant feature of this arrangement was that the center of gravity shifted from the state to the non-political aspects of life. Man’s chief purpose in life was pursued in an order which the government had not created and did not direct. The government, in turn, provided what amounted to a mere auxiliary framework of temporal peace and justice. Its function was limited not only in scope but also in dignity. The state’s proper activity is legislation, and legislation cannot save men’s souls. In the autonomy of the spiritual sphere from government Western man achieved both the social order characteristic of our civilization and the Western form of freedom. For the limitation of government to peace, public order, and justice also permitted and facilitated the freedom of human reason, represented by the Western institution of the university.

A decisive change in this pattern occurred when the rationale of the limited state was secularized by John Locke. Locke taught that “the great and chief end of men uniting into commonwealths” is property, the acquisition of wealth. This teaching, which was almost universally accepted in the West, shifted the center of gravity of human life from man’s relation with God to man’s relation with nature, from the concern for his soul to the concern for his estate. Man’s economic activity was seen as that for the sake of which governments performed their auxiliary functions. Thus Locke continued to think of the state as an order limited in scope and in dignity. Instead of being limited in favor of the autonomous order of salvation, however, he conceived it to be oriented to the service of men’s economic purposes which antedated the state. The state was seen as an order of peace, public safety, and judicial certainty, which enabled men to acquire wealth more effectively than would have been possible otherwise. Beyond the state lies the great private sphere of economics, a sphere which the state with its laws has not created and cannot create because the state has been created by it. This secular sphere of men’s chief end differed from the spiritual order in more than one respect. Above all, unlike the spiritual order, it could not be conceived or experienced as a community beside the state. Rather, it was a sphere of self-seeking activities of a multitude of men, each pursuing his own advantage, an aggregate of private personal interests. The relation of the social order to these interests was one of means to end, so that the purpose of society would be attained as the private interests of multitudes of individuals were more or less satisfied, according to each person’s abilities. The contribution of the state to this end was the procurement of suitable conditions that would facilitate each individual’s success as much as is possible.

To this new version of the limited state Adam Smith contributed the idea that the total aggregate of self-centered individual economic activities constitutes a natural pattern of order. Smith’s symbol was the “Invisible Hand,” the force that in the circulation of goods produces a general harmony. As each individual “intends only his own gain,” he is “led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention,” and “by pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.” Individual self-interest thus was seen as a social function, the motor which propels not merely individual wealth but the wealth of nations. As self-seeking individual activities produced an ordered pattern for the whole, unhindered economic initiative must eventually result in the widest possible individual satisfaction. This is the concept of a natural economic order, an order on which the intentional pursuit of society’s interest by the government could not possibly improve. Locke had said that man’s economic purposes constitute the raison d’être of the state. Smith added that these purposes were unconscious parts of a self-executing harmony which could function perfectly only when left autonomous, and which would procure the end of society, namely the best possible satisfaction of individual material welfare. Thus the economic natural order and its laws now turned into the ultimate cause for the sake of which the state should be limited to minimal activity.

The Locke-Smithean limitation of the state involves also a concept of man that differs radically from that of the Christian tradition. Augustine’s limitation of the state had derived from a psychology that sees men’s loves as the decisive factor in any community, and the love of God as the most significant fact of human life. The community formed by the love of God is then recognized as that which embodies man’s highest destiny. By contrast, Locke’s psychology sees man as significantly self-centered and self-seeking. This follows from the assumption that man’s essential relationship is not that with God but rather that with nature. Foreshadowing Marx, Locke centers man’s social interests in property, and derives property from human labor creating value out of nature’s matter. We have here the difference between what Mircea Eliade has called “religious man,” the man who conceives his entire existence in the light of the Creation and his relation to the Creator, and modem man, who vaunts his mastery over material nature. To these two concepts of man correspond two concepts of the limited state. For Augustine, the community of men in the love of God is a fact of life. As the highest conceivable community, its order lies untouchable beyond the reach of merely temporal authority. For the modern homo oeconomicus, the natural order of the Invisible Hand is his proper realm, an order of intrinsic value which involves the actuality of human freedom as well as the promise of human welfare. One cannot possibly overemphasize the importance of this change from the traditional to the modern notion of the limited state. The state is limited now for the sake of unhindered economic production rather than for the sake of the love of God; the autonomous realm limiting it is no longer the spiritual order of salvation but the natural order of economic harmony.

The difference is not merely philosophical. Unlike the order of salvation, the Invisible Hand implies a pragmatic postulate. It is supposed to function here and now, and there are tangible criteria of its functioning. What is more, the idea that the economic system’s harmonious functioning entails benefits for all arouses certain definite expectations. These soon begin to take the form of demands which people make on their society. We have noted that the task assigned to government was to procure the conditions under which individual interests could attain maximum fulfillment. Society thus became an arrangement for the ultimate purpose of a well-functioning economic order. A corresponding change occurred in the concept of the common good. Traditionally identified with justice, it now takes the form of a macro-economic perspective of society, in which individual material welfare is a function of the overall balance of productive forces. The new orientation, however, has taken a most ironic turn. For the same concepts which first instructed government to stay within limits drawn more narrowly than ever before in history later prompted an ever expanding role of government in the management of the economic system. It is the concern with the health of the economic system as a whole, for the sake of its expected benefits for the individual members of society, that has brought about the gradual incursion of the government into the economic realm and created Western welfare socialism.

The limitation of the state, as postulated by Locke’s concept of man and Smith’s concept of the natural order of society, has a tendency to give way to ever expanding government interference in the economic system. This is the thesis I am here submitting, a thesis that can of course not be adequately substantiated in so brief a space. Only the main arguments can be briefly sketched.

The role of government is to ban from human existence certain evils. When the limits of government are circumscribed by man’s ultimate spiritual destiny and the autonomous life of moral and spiritual order, the business of government will be seen in the “punishment of wickedness and vice, the maintenance of true religion, and virtue.” When man’s purpose, however, is seen as the acquisition of wealth, and the aggregate of individual pursuits of wealth postulated as an order of natural harmony, the evil on which government should concentrate must be found wholly in external conditions which somehow are disturbing the natural harmony of things. Government thus becomes increasingly a device to procure favorable circumstances. The concept of evil is externalized, the source of evil no longer sought in the human heart but in certain undesired conditions that can be removed in order to achieve a more perfect functioning of the social order. Once this is the accepted notion of government’s role, there is room for widely divergent opinions on what precisely are the disturbing circumstances, and what should be done to eliminate them. The limitation of government will be prescribed by these opinions. Locke, for instance, felt that the only thing man lacked for his existence was the assurance of a smooth-functioning judicial system. It was not so much justice that he demanded but rather the predictability in human relations that comes from publicly promulgated laws, impartial judges, and assured enforcement. In other words, men could live well, if only government would see to it that society observed certain “rules of the game.” Now this is one idea of the conditions which man needs in order to live the good life, but not the only one. Other conditions can be postulated, particularly when attention has been drawn to the macro-economic context of the good life. When one begins to wonder under what conditions the economic system as a whole would probably operate as postulated, one may hit upon all kinds of things. The government may be called upon to provide tariffs or other means of protection, to regulate credit, even to lend a supporting hand to the pricing system—all in the name of macro-economic health. Such measures will of course be disputed by those who say that here the government is no longer engaged in the business of securing favorable basic conditions but is rather trying to run the economy, thereby disturbing the laws of the natural order. The point, however, is not whether such government interferences are or are not well conceived and compatible with premises of the Invisible Hand. Once the entire problem of order and disorder has been shifted from the human heart to external conditions, and men begin to blame circumstances rather than themselves for the evils of their social existence, and expect their government to change these circumstances, there is really no cogent reason why any external condition should be kept from government’s correcting hand. Thus the dispute between classical liberals and modern liberal socialists is one conducted on common premises. The premises are that the overall economic order of society is the basis of the good life, that it has inherent value, and that its functioning depends on certain basic conditions to be secured by the government. Given this assumption, the decision of what conditions are an impediment to the system’s smooth operation and what means are required to remove them is one on which opinions may vary widely.

A tendency toward socialist policies thus is built into the assumptions underlying our modern world, since with Locke we see man as the homo eoconomicus whose habitat is the acquisitive society. A socialist government is one that concerns itself authoritatively with the functioning of the economic system. The economic order of which Adam Smith spoke is supposed to engender its own equilibrium, but it is also, on the Lockean premise, supposed to provide individual welfare. The concept of welfare in terms of material well-being is a thoroughly modern one, differing from Aristotle’s happiness as identical with virtue, and Augustine’s goal of fellowship with God. Welfare is what modern man expects of society. The promise of welfare as the result of a well-functioning economic order can almost be called the charter of modern society. Once this promise was grasped by the masses in an age of universal suffrage, the voters would build up enormous pressures on the government to make up for any failures of the Invisible Hand to fulfill it. The welfare state is thus the psychologically and politically unavoidable consequence of the welfare concept of society that stems from John Locke.

One should distinguish between the problem of human welfare and welfare as the utilitarian rationale and purpose of the political order. The latter results from the turn which political philosophy took in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The modern welfare problem, by contrast, is a product of the industrialized and urbanized society as it emerged in the nineteenth century. Masses of individuals found, and are still finding, themselves exposed to indigence of health and estate which they are unable to handle with the resources of rented apartment dwellings and wage income. Facilities larger than those at the command of the urban family are required to cope with many personal emergencies that typically arise in modern existence. We are still groping for the most humane forms of organization capable of dealing with these problems. There is, then, a modern welfare problem. One must, however resist the temptation of jumping from the awareness of a welfare problem to the conclusion of the welfare state. The welfare state is more than an answer to an urgent need: it embodies a concept of man’s purpose in life and the function of political association that far antedates as well as transcends the welfare task in an industrial society. Western welfare socialism has arisen from the relatively recent merger of urban welfare problems and utilitarian political philosophy, compounding the fallacies of the latter with a fallacious intellectual shortcut that makes government instrumental to the solution of almost any human task.

Socialism in the West thus is merely one of the possible variants of Western liberalism, the concept of society centered in the individual and his material aspirations. It is an ultimate concern for private utility and individual welfare that converts itself here into an expanding public management of economic processes and resources. To be sure, the “Individual” is not the concrete living person, whom nobody really consults, but rather a type that is authoritatively defined, together with his presumed needs and aspirations, by the political thinker or government planner. Still, the motivation of Western welfare socialism stems from the same sources as that of Western classical liberalism. It is an individualist rather than a collectivist approach to man and society. It conceives of government as the servant of the ultimate value, acquisitive individual self-interest, and merely occupies one of the extremes of a wide range of conditions that can be conceived as meeting the postulate of welfare.

The socialism of Marx and Lenin roots in entirely different ideas. To begin with, its underlying concept of human nature is collectivist rather than individualist. Marx saw man as being wholly defined by the process of labor. To Aristotle’s formulation “More than anything else, reason is man” Marx might have retorted: “More than anything else, labor is man.” Man is a being whose distinctive feature is that he creates his own life through the objects that he makes out of nature, and who becomes himself in the relations with the objects of his creation. Any kind of separation between him and the fruit of his labor, or between him and his labor process, deprives him of his humanity. This view of man leads Marx into the concept of a collectivist order of labor as man’s proper way of life. For in any other economic system, man would be alienated from his fellow beings and himself, by being alienated from his labor and its products. Private property of the means of production, for instance, enables one man to make another work for him. It also entails a division of labor by which a person is constrained to do the same kind of work all his life, so that he becomes functionally dependent on others. Only if labor were organized under the management of the entire community, and the means of production became the property of all, could man become the master of his own labor process as well as of nature and nature’s laws. It is clear that the Marxist view of man differs as much from that of Locke as from that of Augustine or of Aristotle. The individual as a separate entity is rejected. Freedom and a human life is seen possible only in a collective arrangement of the labor process. All individualism, above all however acquisitive individualism, is condemned as injustice, oppression, and dehumanization. Marx, together with Locke, looks for man’s “chief end” in his relation with nature, but unlike Smith does not assume that there is a humane self-executing order of economic production, as long as private property and individual self-interest is the basis of the economic system.

Marxist socialism, however, is more than the postulate of a collectivist order of labor. More than anything else, it centers in a view of history that asserts a necessary movement of history from one type of society to another by means of revolution. Marxism-Leninism assumes that the conceivable types of society are limited, in fact that there are only five such types, and that the last of these, which is still to come, is the collectivist society in which human nature finally comes into its own. This last society of history will grow out of the revolution of the proletariat, the class of propertyless workers that arises in the last but one society in the series, the capitalist society. The struggle of the proletariat against the class of the bourgeoisie, i.e., the owners of the capitalist means of production, is thus the decisive struggle of history. Through it, the proletariat will overthrow its masters and then use political power dictatorially to “expropriate the expropriators.” The proletariat is described as the only “really revolutionary class” because it fights not for the establishment of any interests of its own but for the radical destruction of the bourgeois society and all its vestiges. Thus Marxist socialism is more than merely a vision of collectivist production. It is also a doctrine of protracted and irreconcilable struggle, a declaration of total war against every now existing social order. It proclaims the action of revolutionary forces, of revolutionaries who pride themselves in having nothing in common with all other fellow-beings and are committed to a radical attitude of hostility until every trace of the now existing society has been eliminated.

For the same reason, Marxist socialism is not a doctrine of state supremacy, particularly not of state management of the economic system. Marx, Engels, and Lenin agree in characterizing the state as merely an instrument of class rule which will disappear when class society gives way to classless socialism. The ultimate vision of these communists includes a society with no political order, a society held together only by the discipline of collective labor. This is not the place to pass judgment on that vision. The point is to note that Marxist socialism, unlike Western welfare socialism, sees no role for the state in the ultimate order of economic harmony which it expects. The state is, however, extremely important in the period of transition from capitalism to communism. This is the period in which the Communist Party is still relatively weak, the forces hostile to it still powerful, the dangers of a relapse into the past lurking everywhere, and the new socialist society still in gestation. Man is still beset by the habits acquired under capitalism, and therefore he is still selfish, individualistic, acquisitive, obstreperous. In this period the state must be powerful to hold down the enemies of the Revolution, to enforce labor discipline, to destroy what Lenin called the “terrible force of habit,” and to press men into a new mold. Thus in Marxist communism the state is above all an instrument of combative power, the major weapon in that protracted struggle that is to fill the entire period of transition from capitalism to communism. It must be totalitarian because the Communist Party is engaged in a total struggle against everything that has existed, because its power is supposed to be adequate to the task of remaking human beings into something they never have been, and, as far as we know, do not want to be. The communist state is totalitarian because the Communists want to play God. They intend to master the human soul, to converge all its powers of loyalty on the Party, to create the world according to their idea of what it should have been. In this enterprise, the state’s monopolistic management of the economy plays an important role, but it is the role of engendering more and more power for the Party. In the period of transition, unlimited and unlimitable power is the Party’s main concern. State management of labor and production represents not yet the way of life, the social order for which communism ultimately hopes. Rather, it is another manipulative operation designed above all to suppress and eradicate everything in the hearts and minds of men that is not wholly amenable to the Party’s leadership.

There is, then, a Western socialism distinct from the Marxist variety. Between the two there are fundamental differences in assumptions and motivations. The socialism that is a noticeable tendency in this country stems from the liberal tradition of Locke-Adam Smith-John Stuart Mill. Its basis is the concept of the acquisitive individual who expects from society the satisfaction of his material interests. Its orientation is toward a nebulous value called welfare. Marxist communism comes from the tradition of speculations about history that runs from Fourier and Saint-Simon to Hegel and Comte. Its basis is the expectation of a wholly new and transfigured world that is to emerge from the revolution of the proletariat. Its orientation is toward the requirements of the struggle that precedes the coming of that world. The difference of assumptions and motivations results in different policies and legal forms. Western socialism emphasizes the supremacy of government in the economic process, but one may say that with all that it is not wholly committed to the abolition of private property or the free labor contract, so that it is likely to retain these institutions while putting an ever heavier hand of government regulation on the freedom of their use. Marxist communism can never reconcile itself with any part of the existing order, but it will readily make use of existing institutions to further its power strategy. One could trace these differences in many details, and one is likely to come out with the clear-cut result that, no matter how objectionable Western socialism may be, it is in no way a road to the regime of Communists. That is an enterprise of quite a different nature.

The differences, however, should not induce us to overlook the similarities among all kinds of socialisms. After all, one could possibly discover still more varieties of socialism around, for instance, the unity-oriented socialism of the Fascists, and the modernity-oriented socialism of Nehru and Nasser. What characterizes all socialism in an institutional respect is the combination of political power with the power of controlling the means of material existence. Political power, we all would agree, consists in the authority to make laws that bind people’s wills in conscience and obligation. Thus, the individual citizen can properly be said to be subject to political authorities. Now if the same set of people or the same agency that makes laws also holds the key to every person’s livelihood and material betterment, the individual is not merely subject to, but dependent on, the government. There is quite a difference between subjection to authority and dependence on controlling power. Not only does a government combining both political and economic power become impossible to control, but it also acquires the means of manipulating people into unresisting subservience. It does not even require the open and harsh methods of compulsion, such as penalties, jails, police force. It needs only to withhold employment, deny advancement, raise the bread basket or lower it, as its interests may require. Instead of addressing the citizens, through the command of laws, as moral beings capable of rational obedience, it controls them as natural creatures who cannot escape their animal needs for food, shelter, cover. In a socialist system, the entire relation between rulers and ruled is changed. A normal political relationship is cast in terms of rational moral assumptions and persuasion within that framework. Under the socialist type of authority, the relation between ruler and ruled is based on the people’s dire necessity, a necessity to which the government alone holds the key. Even should a socialistic government conceive of itself as the servant of people’s needs rather than the exploiter of people’s dependence, it would still be that government which determines which needs should be recognized, and in what way people should be served. The entire public order is distorted when it centers in the material aspects of life where men are by necessity unfree, rather than in the rational-moral order where man, by virtue of the spirit, is free.

In conclusion, we may ask the question why socialism, seeing that it perverts the public order, attracts so much support. The answer can be submitted only in the form of an hypothesis which cannot be proven. It has nothing but plausibility to recommend it. It claims that socialism is a reaction meant to counteract the void left by a state limited on a purely secular basis, a void that left Western man without any order or guidance for his soul and his spirit.

The limited state has been created by Christian political thought. In the Christian order of things, it was man’s community in God that imposed limits on government. Because God himself had created this community, the government was reduced to the practical function of procuring peace, public order, and a modicum of justice. But throughout the Christian era, the government discharged this function side by side with the Church. Thus the realm beyond the temporal order was also a kind of public order, one concerning the spiritual and moral aspects of human life. The temporal and the spiritual order together covered the fullness of human life. The two realms were separate but co-ordinate, and this arrangement allowed for greater human freedom than had ever been achieved before. The limited state could operate within its bounds because beyond its limits the Church provided guidance and community.

The modern era began when the Church first was split, and then rejected by the European intelligentsia. A number of perceptive thinkers then noticed that, with the dropping out of the Church from the public order, a dangerous gap had opened. There was now no publicly recognized spiritual and moral community. Hobbes and Rousseau, among others, attempted to fill that gap by the creation of a “civil theology,” a minimal public philosophy that would be substituted for the spiritual community of the Church. These attempts, as we know, came to nothing. Instead, the place of the former autonomous order of the Church was taken by the autonomous economy. It is for the sake of the system of production that limits were now imposed on government action. This provided for a rationale of the limited state, but not for community. For in his economic activities, man is centered on himself, competing rather than communing with others. And the economic system as a whole is a pattern of regularities rather than one of common values. The new limitation thus placed the state side by side with a realm of public order that spiritually is a void. Man, in so far as he was left to himself by the state, found himself individually alone, or at most embedded in a business company. Society outside of the state became a statistical universe rather than an experienced community. The modern world presents itself to individuals as a medium through which one must claw one’s way to individual goals. As the last remnants of the former community fell victim to the freedom of modern homo oeconomicus, complaints about the emptiness of human existence began to multiply. Man’s loneliness, that is, his lack of community with others, has become the dominant theme of our time, from Riesman’s sociological analysis to the elevation of loneliness to a philosophical axiom by the Existentialists and its endlessly varied representation in modern art.

In this situation, socialism has offered itself as a kind of patent medicine to cure man’s illness. It postulates an extension of the state’s order to embrace the whole man, through the medium of the care for individual material welfare. There is a feeling that somehow, if only the economic system can be managed by the government as the common authority, the economy can become the vehicle of true community. Needless to say, this hope is illusory. Under socialism, man’s loneliness has not decreased. Rather, it has been compounded by boredom resulting from the absence of risk, adventure, and personal achievement which are characteristic of an individualistic economy. We are gradually beginning again to recognize that community among men is a matter of the spirit. It resides only in the acknowledgment of common truths, common meaning, common values, which in turn are rooted in a publicly shared theology or philosophy, a recognized view of what is man, society, nature, and the meaning of life.

The characteristic feature of Western political order is the “civil government,” that is a government barred from publicly entertaining theological or philosophical orthodoxies. The state that is thus limited can administer a true social order only in combination with an antonomous unity representing spiritual truth, be it spontaneous or directed. Our limited state in itself is unable to provide a full social order, and it cannot represent a communal order if supplemented by nothing but the economic system. People can be united only by a shared view of the meaning of life. In other words, the limited state makes sense only in combination with religious community. This does not mean a community of abstract contemplation or mere cult: in the West, spiritual community must always entail active brotherhood and mutual help. The sharing of transcendent truth creates common responsibilities of practical love. It is in the framework of a spiritual community that the task of providing for the welfare of the needy must be solved if that task is not to degenerate into an occasion for the soulless bureaucratic power of an apparatus over dependent beings.

This view could be criticized as a mere personal preference if it were not for the massive evidence of the totalitarian movements that have threatened us in our time. In both cases, we have a kind of substitute church, the totalitarian party, designed to take its place beside the state to provide meaning and coherence to the whole. Needless to say these parties are profound perversions of what a church is and should be. The question is not how we should judge them. The question is why so many millions have acclaimed these perverted churches as filling a deeply sensed need. We cannot have any doubt as to the answer, for the evidence is overwhelming: the people recoiled from the social structure of the West in which they failed to find satisfaction for their spirit’s hunger. We have traditionally kept the authority of faith and that of reason apart from political authority. This order, the glory of the West, worked as long as “separate’’ meant also “coordinate” and “together.” The crisis of the West cannot be solved merely by falling back from totalitarianism to the system of free enterprise. There must be a re-creation of an order of the spirit, in conjunction with which limited government alone is capable of ordering human life.

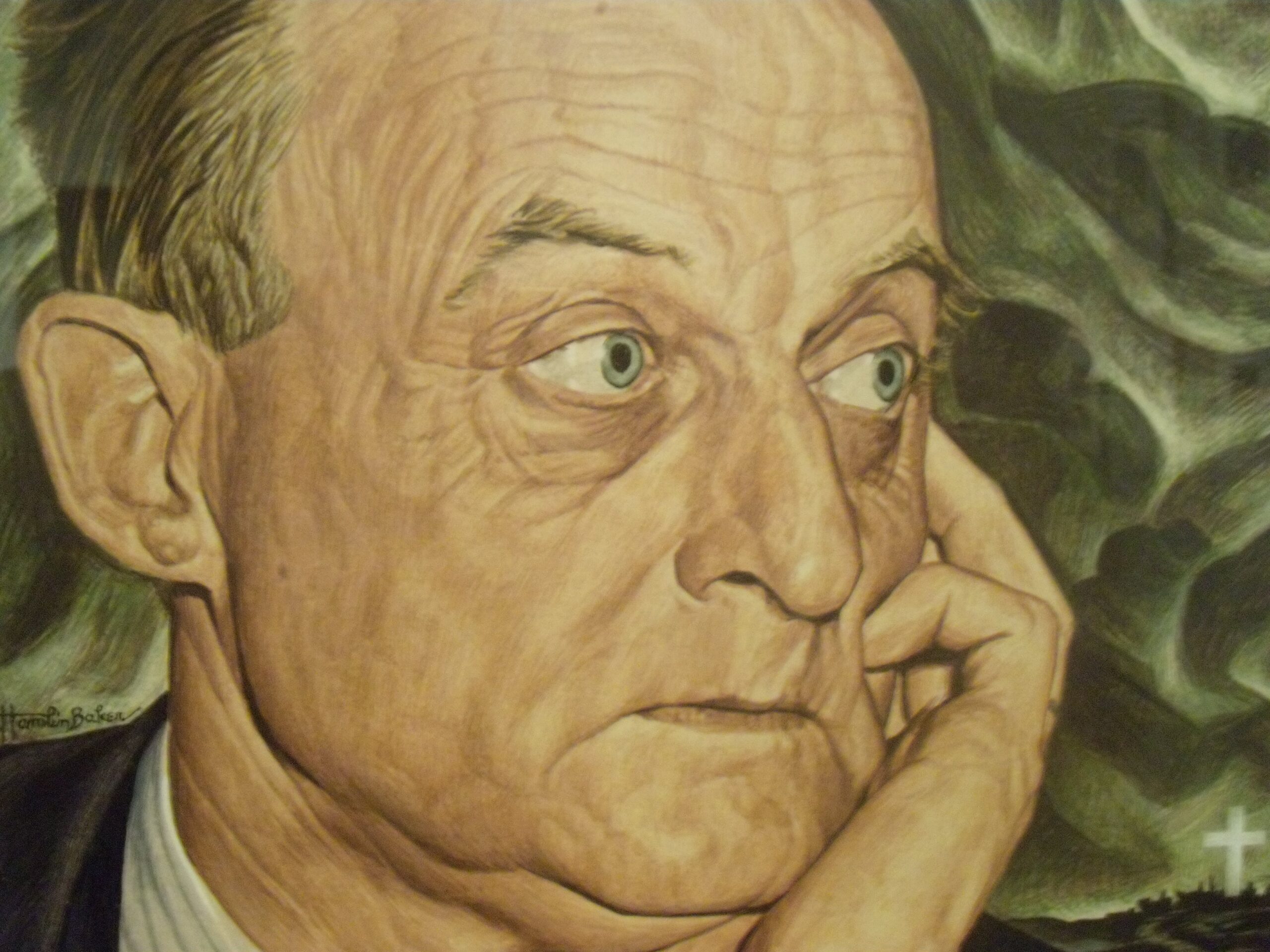

Gerhart Niemeyer was a political theorist and a professor at the University of Notre Dame.