On October 7, 1780, in the wilds of northwest South Carolina, some nine hundred colonial rebels from the colony’s backcountry, fighting for the cause of American independence, executed a coordinated attack on a superior force of pro-British Americans dug in atop a rocky peak called Kings Mountain. The outnumbered rebels, known as “Overmountain men,” charged up the height from several directions, braving withering fire from the entrenched loyalists and eventually overpowering them. It was a signal victory for the rugged revolutionaries.

The loyalists, numbering slightly more than 1,100, suffered horrendous losses: 157 killed, 163 seriously wounded, and nearly 700 taken prisoner (though many captives managed to escape as they were marched to what the rebels considered safer ground). Beyond such numbers was the “depression and fear,” as one British officer put it, spread among Southern loyalists by the rebel victory. Recruitment suffered, and General Charles Cornwallis, commander of British and Tory forces in the American South, now was forced to postpone his planned campaign to move his army north into Virginia, from where he planned to squeeze George Washington’s Continental Army from the south as Britain’s commanding North American general, Henry Clinton, squeezed it from the north.

Indeed, writes Alan Pell Crawford in This Fierce People, “Something seemingly impossible had occurred: an outnumbered gaggle of utterly untrained volunteers . . . had whipped a larger force of well-disciplined, well-supplied provincials and militiamen.” The war, he adds, “had entered a new phase.”

Crawford, a resident scholar at the International Center for Jefferson Studies and author of four previous books of American history and biography, believes that the Revolutionary War’s southern campaigns have received insufficient attention from historians over the decades. In reality, he argues, those campaigns actually determined the war’s outcome. “In battles too few Americans have even heard of,” writes Crawford, “fought by armies commanded by largely unsung heroes, this book seeks to account for the American victory, the reasons for which would otherwise remain a mystery.”

Crawford’s demystifying narrative rests upon a foundation of extensive research and is rendered in sparkling prose, with plenty of vividly drawn profiles of formidable figures caught in the vortex of big, fraught, bloody events. The Kings Mountain battle presents a case in point. It occurred at a pivotal location and a crucial time for pro-British and anti-British forces, both of which were facing plenty of military opportunity and danger in a rapidly fluctuating theater of war.

Until Kings Mountain, the southern war had been going quite well for Britain and its colonial allies. In March 1780, a British flotilla arrived at Charleston (then called Charles Town), South Carolina, with several thousand troops, mostly British redcoats. Soon the city, which was the South’s leading port and a crucial supply hub for anti-British rebels, was under siege. This was bad news for General Washington, back in New Jersey with his army. He had Britain’s General Clinton and his troops penned in at New York, but Clinton seemed in no hurry to hazard a breakout thrust and face Washington’s forces on a field of battle. And Washington certainly had no intention of initiating a foolhardy effort to pry Clinton out of his New York redoubt.

Hence, the war in the North had become a stalemate, with little prospect for any kind of engagement that could win the war. And now things were turning ugly in the South as well. If Charleston fell, Washington told his leading southern officer charged with preventing any such defeat, the result would be “calamitous.” He added that, in such a consequence, “there is much reason to believe, the Southern States will become the principal theatre of the war.” To forestall that worrying possibility, Washington dispatched a trusted major general to South Carolina with 1,400 troops. This was the intrepid Johann de Kalb—German-born, veteran of the War of Spanish Succession and the Seven Years’ War, and utterly committed to the cause of American self-government. He was to join the Continental Army’s southern department.

He didn’t get there in time. On May 12, Charleston fell following a fearsome bombardment from British forces. Along with the city and harbor, the British captured some 5,500 bedraggled rebel soldiers who constituted the main force of southern opposition to British rule. Cornwallis, writes Crawford, “could now secure South Carolina, as Clinton had ordered him to do, and then sweep through North Carolina and into Virginia.” Along the way, he could cajole large numbers of loyalists “to fight back against their independent neighbors, putting down the rebellion once and for all.”

The only battle-ready Continental soldiers left in South Carolina now were the four hundred or so Virginians pulled together by Colonel Abraham Buford. He was promptly ordered to withdraw his troops to safety in North Carolina. But soon he found himself pursued by the so-called British Legion, a cavalry and light infantry force of American loyalists under the command of the British Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton (later promoted to colonel). In late May, the Tarleton force, though outnumbered by Buford’s nearly 380 troops, outmaneuvered them and forced a surrender. In the chaos that followed, Tarleton’s horse was shot from under him, whereupon his men, thinking their commander had been shot during truce talks, commenced a spree of indiscriminate killing of Buford’s wounded soldiers. In the end, 113 Buford men died, while another 150 suffered severe wounds and 50 were taken captive.

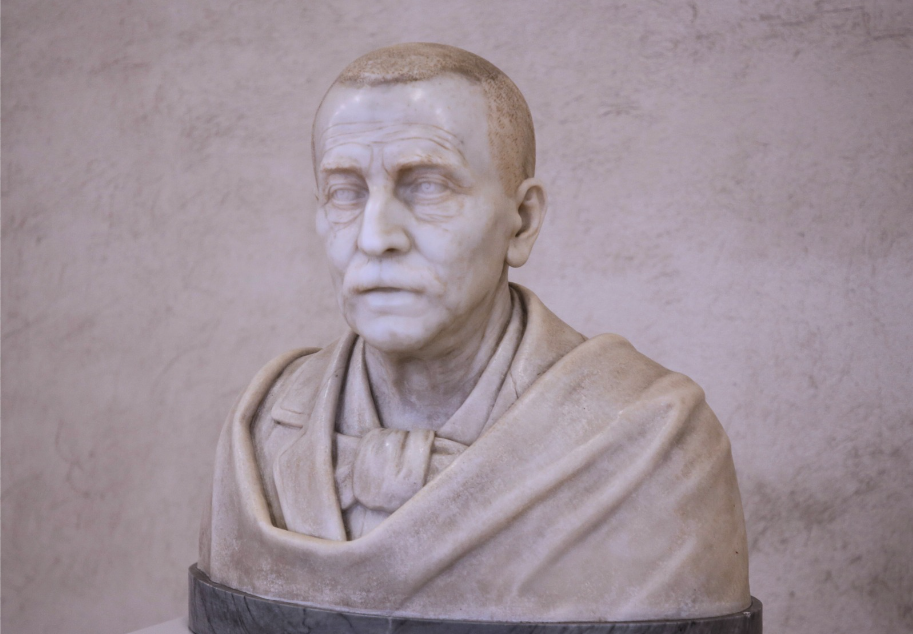

Such events induced an anxious Washington to send to the southern theater a new commanding general. He was the British-born Horatio Gates, a stooped figure of fifty-six years who was known as an adept administrator and popular military leader. Washington didn’t much like the man. He considered Gates to be a bureaucratic maneuverer who sometimes seemed bent on undermining Washington with Congress so he could usurp his command. But Gates had been the hero of the Continental Army’s decisive victory at Saratoga earlier in the war, and so he seemed like the right man for the job.

The immediate task was to work with de Kalb in rebuilding a southern army, beginning with the transfer of troops who had been recruited in Maryland and Delaware. Another infusion came that summer with the arrival of five thousand French soldiers under the command of the Comte de Rochambeau. This represented, as Crawford writes, “the latest . . . expression of French support for the American cause.” With a rebuilt army, the mission would be to engage with Cornwallis’s army and destroy it. That plan didn’t seem very realistic, though, particularly after the next big southern battle, at Camden, South Carolina, in August 1780. As the Gates and Cornwallis armies converged in a pine forest between two swamps, Tarleton’s cavalry quickly encircled the ill-trained Gates regiments, which promptly abandoned the fight and fled. De Kalb was killed trying to rally his men.

It was a devastating day for Gates and his army, with some 900 men either killed or wounded and a thousand captured. In a follow-up battle two days later, Gates lost even more: 150 men killed, 100 wounded, and 300 captured. Tarleton also seized some 800 horses for his cavalry.

Gates survived the battles but lost his job. Washington recalled him to the northern headquarters and sent a new man into the southern cauldron. This was Nathanael Greene, just thirty-eight, an asthmatic who walked with a limp. Though self-educated, he was extremely well-read and seemed to be a military genius. Washington, writes Crawford, “was astonished by Greene’s ability to absorb information and ideas and put them to practical use.”

Greene brought with him what Crawford describes as “a mounting appreciation of . . . what later generations would call guerrilla warfare.” He also quickly concluded that the colonists probably couldn’t win the war by fighting conventional, European-style battles. More to his liking were the exploits of men such as Francis Marion, a laconic backcountry farmer with small appetite for neighborly socializing and a festering yen for adventure. He had gained attention, along with some seventy recruits, for his hit-and-run tactics against the outer flanks of pro-British military units. These actions disrupted the enemy’s supply and communications lines and diminished its mobility and effectiveness. Soon other guerrilla fighters were joining the cause under various spirited leaders who together constituted what Washington called “a flying army.” He urged Greene to maintain a fleet of large flatboats for river crossings that would keep the guerrilla forces highly agile and elusive throughout the region.

As Greene’s quick-hit guerrillas scampered across the landscape, keeping the enemy off balance, the general concentrated on building up his conventional forces. The first sign of success for the new approach was the Kings Mountain victory on October 7. Many other such victories soon followed. In southern locations with homespun names such as Blackstock’s Farm and Cowpens, the Continental forces scored a number of important victories. At Blackstock’s Farm, writes Crawford, “For the first time, American militia had defeated British regulars.”

Greene demonstrated a remarkable bent for unconventional, even highly risky, battlefield maneuvers. At one point he split his force as Cornwallis approached with a larger army, which was considered a foolhardy move by all conventional thinking. But the threat posed to an outlying Cornwallis outpost made it necessary for the British general to split his own force, which paved the way for Greene to outmaneuver him and defeat him in battle. He also set up numerous parallel lines of defense in preparation for combat, telling his men that they could withdraw to the rear after getting off just three good shots. This helped his officers maintain order in the heat of battle and prevent panicked flights.

As the challenges to British rule mounted, some of the Motherland’s inherent weaknesses became evident. As Crawford points out, Britain’s nearly three-thousand-mile supply line posed serious difficulties, and back home economic woes stemming from the expensive Seven Years’ War posed a risk of civic unrest. In the best of times, it wasn’t easy to meet the empire’s global manpower needs, and now the news of more battlefield difficulties was discouraging American loyalists from signing up for the cause. Meanwhile, provisioning Cornwallis’s army was getting increasingly difficult, particularly as General Greene had sent his guerrilla forces into the hinterlands to disrupt the supply and information flows from Britain’s farflung outposts throughout the Carolinas.

Crawford’s narrative makes it easy to see how this American adventure, full of hardship and glory, was the start of something big.

Soon Cornwallis found himself under increasing pressure. He had lost control of the Carolina backcountry and the provisions it produced. He could barely keep his troops fed. It wasn’t even clear that he could maintain control over Charleston, particularly if colonial forces should gain dominance in Virginia. He begged General Clinton to send a contingent of his northern troops down to Virginia to fortify that strategically crucial territory. Clinton refused.

But Clinton eventually allowed a slow transfer of focus, men, and resources from the New York region to Virginia, where supplies were more readily available and from where he could maneuver his troops with greater flexibility. Cornwallis took control of the harbor at Yorktown as an entry point for troop reinforcements and supplies. From there, Cornwallis reasoned, “our cruisers might command the waters of the Chesapeak.”

With Cornwallis concentrating his position at Yorktown, General Washington seized upon the fresh new opportunity. “If the French fleet now in the West Indies could be induced to block off the harbor from the British,” writes Crawford, “Yorktown could be surrounded and the main British army in the South could be destroyed.”

At Washington’s request, Admiral de Grasse of the French navy agreed to proceed to Yorktown with 27 warships and 3,200 men in order to pin down Cornwallis at the Virginia harbor. That meant that generals Washington and Rochambeau had just two months to move their armies, totaling some 7,000 troops, 400 miles from New York to Virginia. “Matters have now come to a crisis,” Washington wrote in his diary, and he “was obliged to give up all idea of attacking New York.”

Though some skirmishing ensued in Virginia and the Carolinas as various military units maneuvered into position, it was now clear to all that the big events would unfold at Yorktown. Washington arrived at the fateful destination on September 14, and his army appeared two weeks later. Cornwallis had about 8,000 troops at the port town, with Washington and Rochambeau surrounding it with a slightly larger force. Washington placed the harbor under siege on September 28, and a bombardment commenced on October 9. After a number of successful attacks on Cornwallis’s fortified redoubts, the British general could see that he was in a hopeless situation. He sent a message to Washington proposing a ceasefire so that representatives of the two armies could negotiate a surrender.

Crawford emphasizes that this didn’t immediately end the war. Though 7,500 British troops were captured at Yorktown, that still left 17,000 in New York and plenty of military challenges for Washington, not least the recapture of Charleston. But it soon became clear that Cornwallis’s surrender had demolished British support for the war. It took some time, but the Continental Congress finally proclaimed the end of hostilities in April 1783.

Crawford is right about the Revolutionary War in the South. It was decisive in bringing the American war effort to a successful conclusion, and it probably hasn’t received the attention in history that it deserves. This book is a tidy corrective to that, and one likely to enliven as well as enlighten most readers. Beyond that, Crawford’s narrative makes it easy to see how this American adventure, full of hardship and glory, was the start of something big.