To get the whole world out of bed

And washed, and dressed, and warmed, and fed,

To work, and back to bed again,

Believe me, Saul, costs worlds of pain.—John Masefield, “The Everlasting Mercy”

During the past year over five hundred of the nation’s newspapers and magazines have carried stories, editorials, and discussions of a remarkable document, The Triple Revolution, signed by thirty-four prominent American intellectual leaders who have demonstrated high moral concern over what is called the American Way of Life. The signers include W. H. Ferry (Vice President of the Fund for the Republic), Michael Harrington, Gerald Piel (publisher of the Scientific American), H. Stuart Hughes of Harvard, Linus Pauling, Norman Thomas, Ralph Helstein, Dwight Macdonald, Robert Theobald, Francis Herring of the University of California, Robert Heilbroner, John W. Ward of Princeton, Everett C. Hughes of Brandeis, and Gunnar Myrdal.1 Mainly an analysis of the relation between automation and unemployment—put most succinctly it calls for a “redefinition of work”—The Triple Revolution seems already to have come to be regarded as a bench mark for proposals to help the poor or to solve the unemployment problem.2

In the belief that men so important and influential as our Revolutionaries will continue to preach their doctrine in season and out of season, and that although much of what they say is fantastic (in a strong sense of the word: the product of nothing more than fantasy), it nevertheless is an important fantasy and has enough plausibility to change the thinking of many, I should like to do two things: first, to state briefly the thesis of The Triple Revolution; and second, to point to and underline certain verbal confusions and errors of analysis which make it difficult to accept as well founded much of what is said.

Let me begin by quoting from the first few paragraphs of the Triple Revolution:

This statement is written in the recognition that mankind is at a historic conjuncture which demands a fundamental reexamination of existing values and institutions. At this time three separate and mutually reinforcing revolutions are taking place:

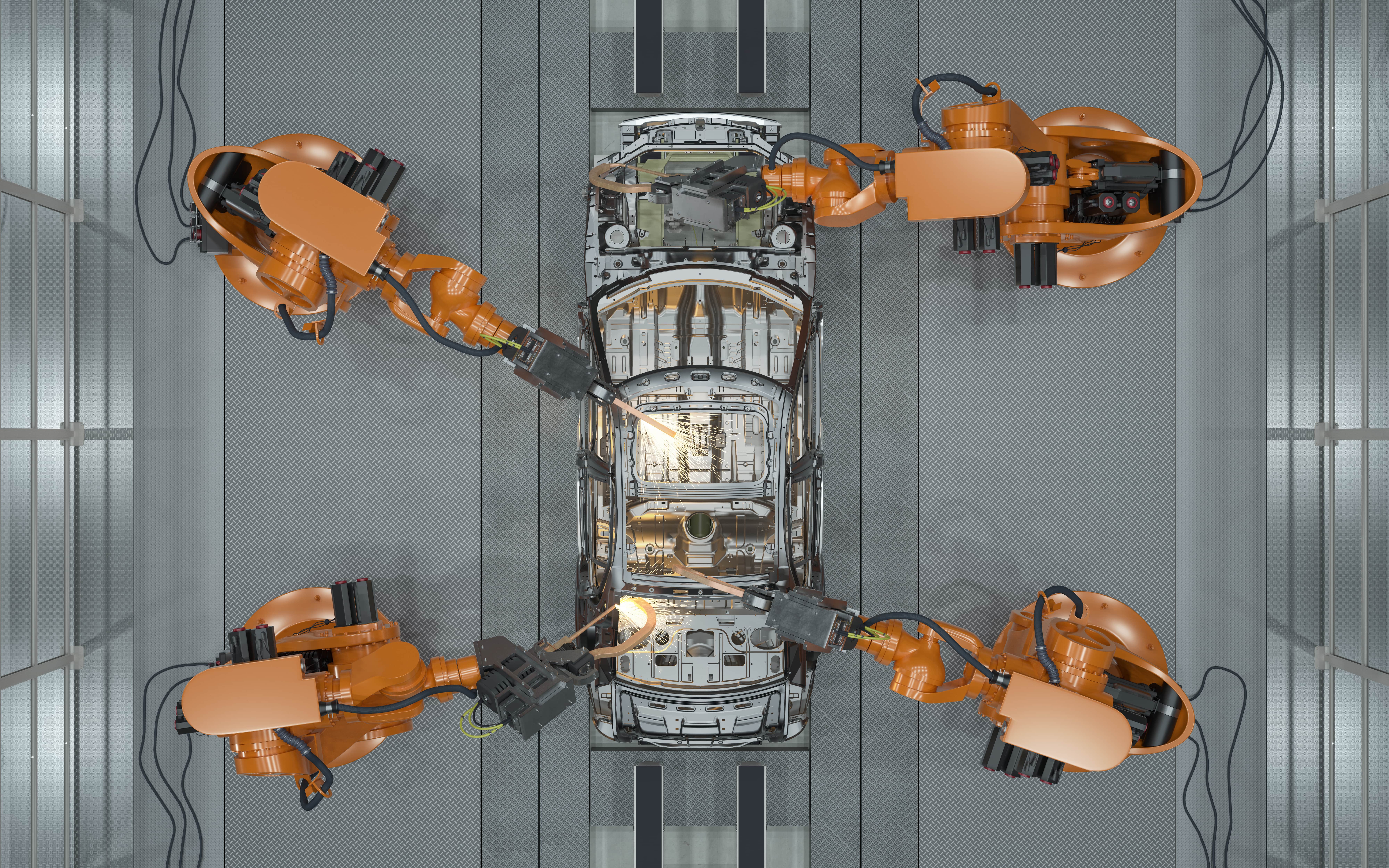

The Cybernation Revolution: A new era of production has begun. Its principles of organization are as different from those of the industrial era as those of the industrial era were different from the agricultural. The cybernation revolution has been brought about by the combination of the computer and the automated self-regulating machine. This results in a system of almost unlimited productive capacity which requires progressively less human labor. . . .

The Weaponry Revolution: New forms of weaponry have been developed which cannot win wars but which can obliterate civilization. . . .The Human Rights Revolution: A universal demand for full human rights is now clearly evident. . . . the civil rights movement in the United States. . . is only the local manifestation of a worldwide movement. . . .

The authors of this document concern themselves almost exclusively with the Cybernation Revolution. The United States, we are told, has been operating on the thesis that every person will be able to obtain a job if he wishes to do so and that this job will provide him with resources adequate to live and maintain a family decently. But jobs are disappearing under the impact of highly efficient, progressively less costly machines. In the developing cybernated system, potentially unlimited output can be achieved by systems of machines which will require little cooperation from human beings. As machines take over production from men, they absorb an increasing proportion of resources while the men who are displaced become dependent on government welfare measures. Our present industrial system was designed to produce an ever-increasing quantity of goods as efficiently as possible and it was assumed that the distribution of the power to purchase these goods would occur almost automatically. But this is no longer a tenable assumption; our major economic problem today is not how to increase production, but how to distribute the abundance which is the great potential of cybernation. The continuance of the income-through-jobs link as a mechanism for distributing effective demand now acts as the main brake on the almost unlimited capacity of a cybernated productive system; for our present industrial and social system is based on scarcity and cannot deal with the facts of abundance produced by cybernation. And so we have rising and excessive unemployment, the underlying cause of which is the fact that the capability of machines is rising more rapidly than the capacity of many human beings to keep pace. But might not the private enterprise sector of the economy keep pace with cybernation? No. Job creation in the private sector has almost entirely ceased except in services: of the 4.3 million jobs created during 1957–1962, only about two hundred thousand (five per cent), were provided by private industry through its own efforts. Cybernation at last forces us to answer the historic question: What is man’s role when he is not dependent upon his own activities for the material basis of his life? What should be the basis for distributing individual access to national resources? Are there other proper claims on goods and services besides a job?

Not the least of our troubles occurs over definitions. We have been using a language based on a theoretical understanding of what is really, today, a rapidly disappearing economic system, and to retain our present definitions of “work,” “leisure,” “play,” and “affluence” is as mistaken as it would be to retain Newtonian definitions of key terms in physics or pre-Darwinian definitions of key terms in biology. One might once have been justified in regarding an unemployed person as lazy, unlucky, indolent, and unworthy—but no longer! Such an implicit definition of “unemployed” is as outmoded as the economic system it reflects. Once we become aware that perhaps 10 per cent of the population will shortly be able to produce all the goods and services needed by the nation, shall we continue to regard the other 90 per cent in the same light in which we viewed yesterday’s 4 or 5 per cent unemployed? The question answers itself.

Now just what are we to do about the fact that under the impact of cybernation the traditional link between jobs and income is being broken? One can no longer have any reasonable hope that ad hoc government welfare measures—public works, “poverty programs,” and the like—can do any more than temporarily alleviate some superficial symptoms: this is the massage and Band-Aid approach. We need solutions that are more fundamental. We must redefine “work”—so that a man’s right to an income will no longer depend on the production of goods and services for which others are willing to pay. We must pay people who do no work—in the old-fashioned sense of “work.” Society must, through its appropriate legal and governmental institutions, undertake an unqualified commitment to provide every individual with an adequate income as a matter of right.

We shall in addition, of course, need to introduce democratic planning by public bodies for the general welfare, a network of agencies through which pass the stated needs of the people at every level of society, agencies which can smooth the transition from a society based on scarcity to a society based on affluence, the abundant society. Only in this way can men be unshackled from the bonds of unfulfilling labor, to become citizens, to make themselves and their own history. Thus speak the thirty-two signers of The Triple Revolution.

As I see it then, the tale told by our Triple Revolutionaries might be summarized under the following headings:

1) Cybernation is making possible the transition from an economy of scarcity to an economy of abundance.

2) This transition will inevitably lead to increasingly high rates of permanent unemployment, to an ever growing “liberated margin,” to use Ferry’s term.

3) This transition should be managed by government planning agencies which will, among other things, regulate the speed and direction of cybernation in order to minimize hardship.

4) High on the agenda of society is the provision of a guaranteed income for all citizens, independent of any work a citizen might or might not perform.

Now most of this is not really new: millenarians, utopians, Marxists and other chiliastic sects have made similar analyses and proposals for generations. As Jacques Ellul sums it up in his The Technological Society: “By the end of the nineteenth century people saw in their grasp the moment in which everything would be at the disposal of everyone, in which man, replaced by machines, would have only pleasures and play.” And more recently we have the testimony of Norbert Wiener, the father of cybernetics: “Let us remember that the automatic machine, whatever we think of any feelings it may have or not have, is the precise economic equivalent of slave labor. Any labor which competes with slave labor must accept the economic conditions of slave labor. It is perfectly clear that this will produce an unemployment situation, in comparison with which the present recession and the depression of the Thirties will seem a pleasant joke.” Still more recently we have the “affluent society” of John Galbraith who comes quite close to the pay-for-play proposal when he writes of the desirability of finding in unemployment compensation “a reasonably satisfactory substitute for production as a source of income.”

But only a heroic exercise in optimism might make it possible to ignore the impact and attractiveness of such errors, however shop-worn and oft-refuted they might be. And so in what follows I should like, first, to make some general comments on the nature of work in the United States and on the call for a “redefinition of work”; next I should like to raise a question or two about the so-called “economy of abundance”; thirdly, I shall wonder out loud about the nature of cybernation, and the nature of the “cybernation revolution”; fourthly I shall look into the crystal ball and attempt to get a balanced picture of what the future of cybernation is likely to be; and finally I shall conclude with some remarks on the proposal that Americans be given a constitutional right to a guaranteed income.

First then, some general comments. Even the briefest survey of the literature reveals the fact that most of the articles and books on the “philosophy of work” and most attempts to analyze the definition and nature of work are by Europeans, most particularly by French writers. There we find an extensive literature on the need to restore the dignity and joys of work, on work as a means of transforming the world, and the like. But in the United States one finds very little such writing, for, at least so it seems to me, two reasons: first, there is not much need to defend in theory what is adequately defended in practice, and the prestige and dignity of work and of the worker is here generally acknowledged; second, there is less need here than in Europe to combat the Marxist philosophy of work on the intellectual level. Speaking in very sweeping generalities, one might say that the American, unlike the European worker, has not been infected by the ideology which represents the wage earner as the victim of ruthless exploitation; and so the American worker is relatively satisfied with his place in society and with his share of its products. In short, the American has not been persuaded that the social system in which he lives is unfair; and he has not been persuaded by the Marxist doctrine that a change in social institutions would entail the abolition of the toil and trouble, the tedium and pain of work, thus making work wholly pleasant, as it was in the Garden of Eden.

Further, it is fairly well recognized that the sort of European criticism of American capitalism which can find “the deepest vice of the capitalist economy” to be “madness of production” (or as Theobald describes our economy in his Free Men and Free Markets, “a whirling dervish economy dependent on compulsive consumption”) is criticism which misses its mark.3 For can one sensibly speak of Americans being infected with “madness of production,” even though we work fewer hours, on the average, than do the people of any other fairly advanced nation in the world? For note that although we have become wealthier and wealthier, we take only part of our increased productivity in more goods and services; another part is taken in population increase (1 ½ per cent as compared with Western Europe’s 1 per cent) ; a third part of our increased productivity has been taken in leisure, freetime: in his recent Religion and Leisure in America, Dr. Robert Lee has estimated that over the past half century, as life expectancy has been extended and the workweek has contracted, the average American has added “something like 22 more years of leisure to his life.” In the non-governmental sector of the American economy, the average productivity of labor has approximately doubled in the past 25 years. Ignoring population increase, it appears that the benefits of increased productivity have been taken by the worker on roughly a 60/40 basis of distribution between income and leisure, that is, 60 per cent of the increase in productivity has been taken in higher wages and 40 per cent in shorter hours of work, in more leisure. Should the same rate of productivity and the same rate of distribution of benefits continue, a 30-hour workweek may be in the picture in another 25 years—and in manufacturing it may occur even earlier; we should then have reached what the world has always considered a utopia as regards hours of work—for in Thomas More’s own Utopia, the inhabitants worked only 6 hours a day. (To be sure, should there be a compulsory shortening of hours with no reduction of wage rates to market levels, institutional unemployment will result, for shortening hours of work has the effect of intensifying the scarcity of capital goods.)

Now when it is asked why Americans work even as hard as they do when they have so very much, part of the answer lies in the fact that rewards are so high for so small a cost of pain and effort: because work in America buys so very large a basket of goods, the attractiveness of leisure is diminished and relatively less leisure is bought. The phenomenon of the “overtime hog” which so surprises Sebastian de Grazia in his book, Of Time, Work, and Leisure, (he says there is an analogy between the “generosity” shown by an employer’s favoring someone by giving him overtime work and the “generosity” shown by a teacher who favors his best pupils by keeping them after school to write on the blackboard 100 times: “I have been a good boy”) is understandable when one realizes that what is important is not how wealthy the worker is—the American automobile worker, for example, is wealthier than 98 per cent of the world’s population—but how high the rewards are for the expenditure of an additional unit of effort.

Gerald Piel wrote, in his famous article, “The End of Toil,” published in the Nation in 1961: “Work occupies fewer hours in the lives of everyone; what work there is grows less like work every year. . . . Compared to the day’s work that confronts most of mankind every morning, most U.S. citizens are not engaged in work at all.” (Note that by the word “work” Piel means not what is usually meant, the occupation by which a man earns a living, but rather the extraction of raw materials and the making of consumable goods from them.) It is certainly true that the character of the occupations by which Americans earn their living has changed over the past century. In the extractive or primary industries (agriculture, forestry, fishing, and mining) the percentage of the labor force has dropped from 54 per cent to 10 per cent in the past 90 years. The percentage of men employed in manufacturing and construction has, on the other hand, grown from 22 per cent to 32 per cent in the same period, though it now appears to be leveling off, that is to say, as wealth increases the elasticity of demand for fabricated products is less than it once was. Demand is however rapidly increasing in personal service and life-enriching industries; people want to spend a relatively larger proportion of their budget on education, entertainment, travel, medical services, and the like—and employment has more than doubled in these industries in the last 90 years, and now approaches a total of 30 per cent of the labor force.

Now of course increased productivity has its costs, principally those connected with the “division of labor,” “specialization,” “comparative advantage,” or what Marx called “detail work” which, he claimed, “converts the laborer into a crippled monstrosity by forcing his detail dexterity at the expense of a world of productive capabilities and instincts.” Though this description is perhaps exaggerated, it does appear to be true that as Donohue has remarked in his book, Work and Education, “the detailed division of labor, so fruitful for mass output, is pointless when the workman’s own development is the aim,” and that at least that sort of joy in labor which results from one’s aesthetic appreciation of his own skill and of its product tends to be diminished—though anticipation of the enjoyment of higher wages seems to many men worth paying this cost. The monotony and tedium of specialization may continue to be increasingly overcome by machines. But machines will not diminish the interdependence that results from a desire to increase productivity through specialization: this dependence of one man on others’ tastes and abilities may well be amplified. This is not, however, to say that interdependence creates a need for an increased range of government activity, for, as George Stigler has said, “after all, the market is the prime center for the coordination of specialists.” Finally, division of labor intensifies the innate inequality among men—if everyone had to be a jack-of-all-trades, some would be better at it, but the range of rewards would be narrowed.

Another fact about the nature of work in the United States worth a brief note—a fact which has considerable importance, as F. A. Hayek has argued—is this: we have gone from a time, in the early nineteenth century, when 80 per cent of the working population were self-employed enterprisers, to a time, today, when fewer than 20 per cent of the working population is self-employed (and included in this 20 per cent are a large number of farmers dependent on government subsidies). Thus by far the greater part of our population increase in the last 150 years has been made up of those who work for wages. Now one of the great advantages in working for another lies in the fact that when a man has sold only part of his time, only part of himself, for a fixed income, there can be a fairly sharp distinction between private and business life. In effect, the man who sells his labor for wages is relieved of some of the responsibilities of economic life in return for giving up the chance for a higher income open to one who takes bigger economic risks in his own business. But a consequence of a man’s being relieved of the responsibility of risky decisions, of his being responsible only for giving a day’s work for a day’s pay, is that if economic disaster in some form does strike his employer, he quite naturally feels that such a disaster is clearly not his fault; he is not to blame since he has been doing his part and he did not make things go sour. He, the man who works for wages—and he forms the great majority of the electorate—will want to be made secure from economic disaster, will tend to insist on economic security, a security guaranteed by government if that seems to him necessary. And if some of the government activities undertaken fail of their purpose and actually do more harm than good, the government welfare sector of the economy will grow enormously, feeding, as it were, on its own failures.

Now with all this as a background, let us return to our document. The authors of The Triple Revolution, as I have indicated, call for a redefinition of “work’’ (and also of “leisure,” “scarcity,” “abundance,” and the like). Now what could a man who says: “Let’s redefine the word ‘x’” possibly mean? One thing that could be meant, for example by a dictionary-maker, is that the range of things referred to by a usual definition of “x” is larger or smaller than the range of things people generally use the word “x” to refer to. But surely the word “work” has not yet changed its scope in this way—a man who does nothing to earn a living is surely said not to be working. Nor is it likely that our Revolutionaries are simply insisting on their own right to use the word ‘‘work” in an unfamiliar way, but in a way that pleases them. It appears to me rather, that when our authors call for a redefinition of “work,” they are doing two things. They are saying: “Let us retain the laudatory connotation presently attached to ‘work,’ but let us cut it adrift from its present objective reference, its present extension only to men who produce products other men compete to get.” But this would be an unreasonable proposal unless they were also saying implicitly what they also say explicitly: economic theory needs revision. Present economic theory is no longer useful for describing and analyzing our brave new world. And since this is so, our conceptual schemes need rearranging, perhaps in much the same way that certain medieval conceptual schemes needed rearranging when we passed from the medieval economy to the modern industrial economy. For with this passage, economic phenomena could no longer usefully be discussed in terms of “just price,” “usury,” “interest,” “surplus,” and the like—as defined in the Middle Ages. These terms, if they were to be useful at all in the modern world, needed to be redefined, for without redefinition one would find it impossible to say what one wanted to say. So when our authors say: “Let’s redefine ‘work’ and ‘leisure,’” they are saying: “Let’s disregard, ignore, cancel out of our thinking certain properties heretofore attached to the words ‘work’ and ‘leisure,’ for these properties are no longer important or relevant in our world of cybernation. We shall not understand the modern world of abundance unless we develop a new economic theory, with new conceptual schemes, and new definitions of the key terms used to talk about these conceptual schemes.”

Let us now, briefly, examine the notion of an “economy of abundance,” for everything that was said about the need for redefinition and out-of-date economics makes sense only in a context, not of scarcity, but of abundance. The thesis we are examining is that cybernation is the instrumentality that will bring the American people from an economy of scarcity to an economy of abundance. But what precisely is the nature of this goal? What would an “economy of abundance” be like if we achieved it? Well, if we use the categories of what we are told is a soon-to-be-outmoded,“pre-Copernican” economics, we can make a distinction between “free” goods and “economic” goods: of the former everyone has as much as he would like to have without sacrificing anything—the classical example is air, a free good for most people most of the time; economic goods are scarce goods, those one would prefer to have more of, those which one cannot get more of without paying a price, without sacrificing some good possessed. In terms of this distinction, one might describe an “economy of abundance” as one in which there are no scarce goods, a world in which everyone has as much of everything as he wants. The world of abundance is one in which, if everyone were to be given, as in fairy tales, three wishes by his fairy godmother, no one would bother to use up his wishes to get more goods and services.

Now in the doctrine of Karl Marx, scarcity is a historical and accidental category which will be forever eliminated by the abolition of private property, when mankind will leap from the realm of necessity to the realm of freedom. Men will still “work” (in a redefined sense), for work will then be “the primary necessity of life,” but, as in the Garden of Eden, work will no longer be painful, it will be pleasant. Of course one way to achieve such a goal would be to tinker with men’s minds so that they would not want anything more than they have—but one might have attempted this at any time in the past, no matter how wealthy or poor the population. Marx thought that direct tinkering would be unnecessary once men’s desires for private property would have been eradicated—and I agree. But the eradication of desire for private property would itself, I think, call for a great deal of brain-washing, for I see no evidence at all nor do I know any arguments which would lead a person to believe that a change in social institutions would of itself entail the eradication of desire for private property or for more goods and services than he has.

Returning now to our Triple Revolutionaries, for whom scarcity is a historical category, as it was for Marx and for the Saint-Simonians, one might put the question: suppose cybernation does make possible a doubling, a tripling, a quadrupling of the national output of goods and services—or suppose, for example, that 50 million robots marched out of the bowels of the earth and went to work for no pay other than an occasional squirt of oil on their joints. Suppose the average family income rose from $7,000 a year to $50,000 a year—would we then have an “economy of abundance”? No, not as I have defined “economy of abundance”—unless people with $50,000 a year have all their desires satisfied, which, casual observation leads me to believe, is highly unlikely; it would still be necessary to allocate (choose between alternative satisfactions) and to economize (satisfy desires with the least expenditure of resources), and so there would be no grounds for abandoning traditional economic theory. To be sure, people would be wealthier—but Americans are more than twice as wealthy today than they were a generation ago. So how is cybernation relevant to the problem of economic scarcity? If there would still continue to be scarce goods, is it reasonable to say, as does Mr. Ferry:

Cybernation signifies the opening of the era of abundance. Since economics is the science of the allocation of scarcities, cybernation as the main agent of plenty mandates the reformation of economic theory. . . . all of the sciences are burgeoning with fresh approaches to old matters except, alas, the political economic science. Here is the last pre-Copernican stronghold among natural and social scientists, heavily patrolled by economic astrologers and other magistrates of the status quo. The most notable aspect of our world of novelty and rapid change is the unwillingness of economics and political science to perceive it, and their hostility toward those who do.4

Of course it is true that people who have $50,000 a year to spend have demand schedules different from those who have only $7,000 a year to spend—but do not both have unsatisfied wants (or velleities, if you will)? To sum up: if cybernation will bring about an era in which everybody’s wants are satisfied, economists will certainly be out of a job; but if cybernation will only make possible considerably greater wealth, then economists will still find a world of scarcity to analyze and on which to exercise their talents. We have never yet been favored with a world in which even a single person has had all his needs, wants, desires, velleities, and whims satisfied; to expect cybernation to bring about a world in which everyone has all his wants satisfied—with the inevitable mutual conflicts of desires—is not only unlikely but logically impossible, given men as we know them. Lewis Mumford once classified Utopias as being either Utopias of retreat or escape from the world, or Utopias looking toward the world’s reconstruction. With all respect, I submit that the notion of an “economy of abundance,” at least as presently described, is an element of the former and not of the latter sort of Utopia. But saying this is not at all to minimize the impact or the applicability of another of Mumford’s remarks: “Nowhere [Utopia] may be an imaginary country, but News from Nowhere is real news.”

Now I might very well be accused of the fallacy of ignoring the issue by a misinterpretation of what Marx and/or our Triple Revolutionaries have meant by “economy of abundance.” Surely neither is talking about a world in which all goods are free goods. Rather what both are saying is that each and every citizen will have all his needs satisfied, not that he will have all his wants satisfied. Cybernation will give us the power to satisfy not all our wants but all our needs. Now the “logic” of the word “need” is interesting. If I say “I need x,” there is by contrast with my saying “I want x,” a connotation of constancy, absoluteness, definiteness, a suggestion that what I say I need is almost physiologically demanded, and a suggestion that costs are irrelevant. I can compare, for instance, my wife’s telling me, “I want a new rug” with her saying, “We need a new rug.” In English we speak not of urgent, critical, crying, vital, or essential wants—but of urgent, critical, crying, vital, or essential needs. To speak then of an economy as potentially capable of satisfying all our “needs” is to imply that there is a constant and unchanging set of goods and services called “our needs” and also that a finite amount of wealth will enable us to satisfy these needs. But as economists point out over and over again, the notion of “need” is not an analytically useful one. We are inclined to say that we need too many sorts of things, from more protein in our diet or a longer vacation, to a new car, more highways, more and better teachers, more missiles, more water in California. This is to say that “need,” like “want,” is a vague word, connoting constancy and definiteness but denoting nothing more definite than “want.” “I need” is used persuasively to say “I want.” When someone says: “I (or more usually, we) need x,” one should, I think, follow Alchian and Allen’s suggestion (in their brilliant new textbook University Economics) and respond: “You say you need x, but in order to achieve what? at what cost of other goods or ‘needs?’ and at whose cost?’’ These questions are obviously relevant when someone says “I want x”; they are no less relevant when someone says “We need x.” The only practical way, of course, of distinguishing “wants” and “needs” is to give some authority the power to define what are to be counted as “needs” and what are to be counted only as “wants”—but this course of action has some rather obviously undesirable consequences which need not be discussed here.

And now we come to Cybernation. What does the word mean? What is cybernation likely to bring us? and when? There is a story told about the Monroe Doctrine which illustrates what I first want to say about cybernation. It seems that there were two patriotic Americans who met on the street one day.

“What’s this I hear about you?” demanded one, “That you say you do not believe in the Monroe Doctrine?”

The reply was instant and indignant: “It’s a lie. I never said I didn’t believe in the Monroe Doctrine. I do believe in it. It’s the palladium of our liberties. I would die for the Monroe Doctrine. All I said was that I don’t know what it means!”

I too am often puzzled about the meaning people attach to “cybernation,” or “automation,” the more usual word. In many contexts these words are nothing more than symbols standing for progress and change in the twentieth century. People are fascinated by the fantastic performance of automated machines, and perhaps no topic since the evolution of the human body whets the appetites of Sunday-supplement readers more. Now the authors of The Triple Revolution are admirably clear about what they mean by “cybernation,” defining it as the coupling of computers with automated self-regulating machines. What is somewhat puzzling about what they say is precisely why “cybernation” rather than “automation” is the sign in the sky: why is the marriage of computers with automated machines more important than so-called “Detroit automation” (by which is meant the use of transfer equipment to move work from one automatic machine tool to another and interlocking these tools to get high utilization), or more important than automation resulting from an invention through which, at no greater outlay of capital, the same job can be done with less labor. Whether one or another particularly advanced form of technology is used would appear to be unimportant in the context in which our Triple Revolutionaries speak. The only advantage I find in the word “cybernation” over the word “automation,” other than the fact that “cybernation” is more likely to displace white collar workers in some jobs than is “automation;” is that “cybernation” has a slightly stronger emotive impact on those who are struck—and who isn’t?—by the prestige of science and science-laden technology.

Now for the question, is automation something new? The answer is yes and no. The principles themselves are embodied in many natural processes, both living and non-living. And not only have men recognized the existence of self-regulating mechanisms, they have deliberately constructed them for a hundred years or so: witness Basile Bouchon’s technique for weaving patterned silk in 1725; Edmund Lee’s automatic control for windmills that permitted the tower to turn with the breeze, invented in 1745; James Watt’s flyball governor for regulating the speed of steam engines—and even back in ancient Greece, Hero of Alexandria invented a machine embodying an automatic mechanism for opening and closing temple doors. (Another ancient Greek, Aristotle, caught a glimpse of an automated utopia when he wrote: “If every instrument could accomplish its own work, obeying or anticipating the will of others . . . if the shuttle would weave and the pick touch the lyre without a hand to guide them, chief workmen would not need servants, nor masters need slaves.”)

Nonetheless, though the general notion of automation is not something new, it is certainly true that it is only in the twentieth century that automation has come into its own. As Ernest Nagel, the eminent philosopher of science from Columbia, has written:

When human intelligence is disciplined by the analytical methods of modern science, and fortified by modern material resources and techniques, it can transform almost beyond recognition the most familiar aspects of the physical and social scene. There is surely a profound difference between a primitive recognition that some mechanisms are self-regulating while others are not, and the invention of analytic theory which not only accounts for the gross facts but guides the construction of new types of systems.

Nagel also notes in his article on automation that the introduction of automated machinery was only in part motivated by rising labor costs:

Many articles in current use must be processed under conditions of speed, temperature, pressure and chemical exchange which make human control impossible, or at least impracticable, on an extensive scale. Moreover, modern machines and instruments themselves must often satisfy unprecedentedly high standards of quality, and beyond certain limits the discrimination and control of quantitative differences elude human capacity.5

Regardless, however, of how new automation or cybernation is, surely what is important in our context is whether these new forms of technology are likely to cause changes of a different quality or of considerably different magnitude than technological changes in the past. The meaningful socio-economic test of the putative newness of automation is to be found in the difference it is likely to make in the ratio of substitutability of capital and labor. I find in the discussion of this issue in The Triple Revolution, and elsewhere, an implicit confusion of considerable importance: a confusion between technologically efficient production and economically efficient production. Another confusing assumption I find implicitly made is that automated machines and computers are free goods—much as though these machines were like the hypothetical 50 million robots I mentioned earlier which marched out of the bowels of the earth at no cost to anyone. Let me speak briefly on these points, in order.

A technologically efficient technique is one that maximizes the product given the inputs and the technology used. But there is generally more than one technically efficient way of producing any specified output. The socially important question is: which of the technically efficient processes is the economically efficient method, the one that achieves a given output at minimum cost? Morris Motors of England first used “Detroit automation” in 1927; the method was technically but not economically efficient at that time, because the output might have been produced at lower cost by the simpler, labor-intensive techniques then available. In Alchian and Allen’s textbook this problem is given to the student: “A jet plane can fly across the U.S. 3 hours faster than a propeller plane. Which is the more efficient?” The answer given at the back of the book is short and sweet: “Can’t tell from that information. Don’t know costs.” (Compare W. H. Ferry’s analysis: “Let us consider the vexing situation of our airlines, squirming and tortured in the technological vise. There are not enough passengers to fill the bigger and swifter and far more expensive jets. But the airlines have to buy these commodious and speedy machines, not because they are profitable but because they have been made available by technology.”)6

That brings me to my second point, a point so obvious that I can with equanimity be quite dogmatic: machines, whether automated, married to computers, or what have you, cost money—they are not free. Ignoring entirely for the moment the impact of new machines on employment, let me quote some estimates on the cost of automating from a recent article by Yale Brozen of the University of Chicago, who speaks with considerable authority in this field:

To automate as completely as possible with present technology, only one major segment of the American economy, manufacturing, would require an expenditure of 2.5 trillion dollars [this comes to $12,000 per man, woman, and child, and the total stock of inanimate goods in the United States has been estimated to be worth only ⅙ more, 3 trillion dollars]. Even to modernize manufacturing to the levels of the new plants built in the 1950s would require over 500 billion. Since total spending on new plants and equipment in manufacturing amounts to about 15 billion per year, American manufacturing could not be modernized even to the technology of the level of the 1950s for over 30 years, and this is under the extreme assumption that all the expenditure is used for modernization and none for expansion. With the current division of capital outlays between modernization and expansion, modernization to the level of new plants of the variety built in the 1950s would require about 50 years. To automate completely the manufacturing industry with no increase in total output would require two centuries at current rates of modernization. If we expand output at the rate necessary to keep up with population growth, however, present rates of capital formation will never result in complete automation of manufacturing unless the cost of automation is reduced to less than ⅙ of its present expense. This is unlikely to occur within the foreseeable future.7

Having given some evidence for believing that automated machines are not free goods in the world we live in, let me, in effect, relax that assumption and, forgetting about the way things really are, proceed on the assumption I sometimes find implicit in The Triple Revolution, that machines are free or, what is equivalent, talk about a world in which 50 million (free) robots march into factories and offices and replace workers. Would this be a bad thing? Yes and no. It would be wholly good for those who were working at jobs robots did not take over: robot-produced goods would be considerably cheaper, and an automobile that today costs $2,000 might tomorrow cost only $1,000 or less. It would be partly good for those whose jobs robots took over—goods would be cheaper for them too; but partly bad for this class to the extent that, like any technological change, job reallocation would occur and cause hardship. I think it is perfectly clear, assuming that the introduction of robots does not give us an economy of abundance in which all wants are perfectly satisfied at no cost, assuming that people would still want goods and services not supplied fully by robots, assuming, that is to say, that economic analysis is still viable, that there is no reason to believe that any permanent unemployment would occur, that the problem we would face would be anything other than a monstrous task of job reallocation. In effect, if I were fearful of being automated out of a job, my fear would not be a fear of not finding some job or other, but a fear that the process of reallocation would be costly in terms of paying the price of informing myself about the best and highest-paying and most satisfying alternatives. These costs might be very high, but they are no different in nature from the price I would have to pay if I were fired tomorrow because, say, of a drop in enrollment in my college. If fired, I would certainly not take the first job offered (cutting my neighbor’s lawn, taking a paper route, etc.) for I should consider it rational to spend time finding the most productive job I could perform—the job that someone would be willing to pay me most to do (given my taste qua teacher for doing as little “work” as possible). It would be costly to remain unemployed; but I should consider the cost worth paying. “The problem is not one of too few jobs, but of too many jobs; the problem is deciding which jobs or tasks to perform and which jobs to leave unperformed because they would yield a less valuable product. This is the persisting problem of labor reallocation.”8

Now I must confess that I am to some extent avoiding a problem posed by our Revolutionaries, for although at times they speak of “progressively less costly machines,” they also speak, at other times, of expensive machines taking away jobs from men—the salary, as it were, goes to the machine. But I cannot even imagine a world in which the men who make machines are not paid, or in which the machines themselves are somehow “paid” but do not spend the money, or hoard it, nor . . . well, I just don’t know. My imagination boggles at this sort of economic ribaldry, at the notion of machines permanently disemploying, not forcing the reallocation of, ever-increasing numbers of men. As Ramsey has said: “What you can’t say, you can’t say, and you can’t whistle it either!”

Perhaps it might be appropriate to say a word about unemployment among the unskilled—which ties in with the third of the revolutions discussed by our Triple Revolutionaries, the one which involves the struggle of Negroes for employment. Again the appropriate question to ask is: are there goods and services that people want and that could be provided by the unskilled? But rather than argue the point, let me simply point to what seems to me to be the relevant experience of West Germany since 1948. In a recent article in the New Republic, Edwin L. Dale, Jr., writes as follows:

. . . the influx into the German labor force during many of the past 15 years was greater proportionately than our present labor force growth. In addition to the refugees, the movement off the farm in Germany was greater than here and all these people have jobs too. Still the demand for labor was not satisfied. And so now half-literate Turks are being transported to Germany and put to work. They are about as unskilled as it is possible to be, and they cannot even speak the language. Yet they all have jobs. This is to say nothing of Italians, Greeks, and Spaniards. And to cap this story, the rate of “automation” in Germany has been consistently faster than ours, as measured by the annual rise in the output of each worker per hour or day or week. Today, despite all these things, there is a severe labor shortage in Germany, with 6 vacancies for each unemployed worker.9

Dale also says that there is “some evidence that the rate of unemployment among the unskilled is lower, in relation to the total unemployment rate, than it was ten years ago.”

We come now to “the democratic requirement” of “the conscious and rational direction of economic life by planning institutions under democratic control.” There is implicit in such characteristically socialistic proposals two assumptions: first that individuals do not know what is good for them; and second, that government agents do know what is good for people. The first assumption is perhaps more fundamental. As Stigler has written: “The decline of confidence in the competence of the individual has in fact been the basic reason for the vast extension of the state’s regulatory activities.” But note that even if the first assumption were warranted, its truth would not entail or even imply the truth of the second. Let us, however, suppose what is contrary-to-fact, let us suppose that both assumptions are true. Then it seems to me to follow as does night the day, that unless our omnicompetent planners are Gods who permit evil in order to bring forth greater good, it would be wrong, terribly wrong, to let people live in a non-totalitarian society. We (morally) ought to demand to live in a closed society built on the Platonic or Russian or Chinese model! We might still call our state “democratic” as the Russians define “democracy,” or as our Revolutionaries define it: “a community of men and women who are able to understand, express and determine their lives as dignified human beings” (or as Ferry independently defines it: “I identify democracy closely with a concern for the general welfare and as the best means of achieving it”). But no matter what we call our desired and warranted form of government, if we can be sure that somebody surely knows what is best for us and is surely willing to act in our best interests, it would be wholly unreasonable and vicious of us to refuse to welcome with tears of gratitude our salvific masters.

But of course all this is absurd—the second assumption of omniscient and omnicompetent and benevolent master-planners bears no relation to reality. And why is this fact not analytically self-evident to our Revolutionaries? I must confess that I do not know.

Now we come to the feature of The Triple Revolution which has aroused more criticism and scorn, and sometimes amusement, than any other—the “pay-for-play” proposal, the proposal urged that “society, through its appropriate legal and governmental institutions, undertake an unqualified commitment to provide every individual and family with an adequate income as a matter of right.” It was this feature that aroused the most editorial comment: “Just Roll Around Heaven All Day” was the title of the New York Herald Tribune’s editorial; “The More Abundant Hell,” said the Chicago Tribune; “Program For A Frightening Future,” proclaimed the Wall Street Journal. Other editorials were headed: “Shiftlessness in High Gear,” “Funny Money People,” “All Pay And No Work.” Mr. Ferry wrote recently: “Many if not most readers got the impression that we were in effect advocating the indolent society, a cushioned technological epiphany in which cashing government income checks, beer drinking, television watching, and general lollygagging would be the main activities of the majority of the people.”10 I am reminded of a brief Boswell-Sam Johnson dialogue: Boswell says, “So, Sir, you laugh at schemes of political improvement?” Johnson: “Why, Sir, most schemes of political improvement are very laughable things.” My own position on this “guaranteed income” proposal is not that it is laughable, but that it is unnecessary, for reasons I have suggested. Victor Borge tells the story of his physician-uncle who became despondent on realizing that he had discovered a cure for which there is no disease. There is a sense in which, I think, this ought to be true of our Triple Revolutionaries.

Nonetheless, I find some merit in the proposal, not to cure the plague of increasing permanent unemployment caused by automation—there is no such plague—but as a way of helping those who are both poor and unemployable, a way preferable to the hodge-podge of welfare measures now in existence. The authors of The Triple Revolution are aware of this feature when they write that: “The unqualified right to an income would take the place of the patchwork of welfare measures—from unemployment insurance to relief—designed to ensure that no citizen or resident of the United States actually starves.” (I confess to some uneasiness over the expression “unqualified right to an income,” for one normally speaks of “rights” in a context of justice, and this is, using words as people ordinarily use them, a “right” to charity or mercy.)

Ferry, in some of his very recent articles, notes that the authors of The Triple Revolution might have cited Professor Milton Friedman in support of the minimum income scheme. And well they might. Friedman has proposed what he calls a “negative income tax,” which sets a floor below which no man’s income, including the subsidy, is to be permitted to fall. According to this plan, if a man’s income is low enough, he not only pays no income tax, he even receives a subsidy to bring his income up to a given minimum. In support of this, Friedman argues, first that help would be given in the most useful form, cash; second, that this scheme makes explicit the cost borne by society; third, that it operates outside the market, and so does not, as do most present welfare measures, distort the market or impede its functioning; and finally, that this program would help the poor precisely because and to the extent that they are poor, not because they are farmers and some farmers are poor, or because they are too old to work and some who are too old to work are poor. Friedman notes in a recent article that in 1963, $45 billion was spent on direct welfare payments and programs: old-age assistance, social security payments, farm price-support programs, public housing, and so on.11 (This figure does not include payments to veterans or the indirect cost of minimum wage laws, tariffs, and the like.) But if this $45 billion had been used to give cash payments to the poor, each consumer unit among the poorest 10 per cent of our population could have been given $7,800; or the poorest 20 per cent could have been given $4,000; or $2,250 could have been given to that one-third of the nation which is ill-fed, ill-clothed, and ill-housed. (Observe also that today only one-eighth of the population has an income as low as that received in the middle Thirties by Roosevelt’s one-third.)

And may I add parenthetically in reference again to the third Revolution referred to by our authors, that if one wants to help Negroes, the most effective way to help them would be to give them cash: they would never consider themselves worse off with cash than with, for example, below-cost public housing; and if they preferred other goods to housing, they would consider themselves better off with cash. Perhaps the utopian spirit of our Triple Revolutionaries is catching, for I’d like to conclude with a utopian proposal of my own. If one can argue that a man who has been unjustly incarcerated for a period of time is owed, in justice, some monetary recompense for the injustice done him, then one might argue that Negroes who were coerced into slavery are owed recompense. I should find nothing inconsistent with my own principles in visiting the sins of fathers on children to the extent of taxing ourselves to give each Negro now alive a monthly (say for 10 years) sum of money as a gesture of recompense for the injustice done their ancestors in the past. Note too that it is easier to refuse to serve a poorer Negro than to refuse to serve a richer Negro, and that almost everyone who finds Negroes objectionable for one reason or another, finds richer Negroes less objectionable than poorer Negroes.

Robert L. Cunningham was professor of philosophy at the University of San Francisco.

- Myrdal, in signing comments, “I am in broad agreement with this Statement, though not entirely so.” ↩︎

- The same “revolutionary” thesis is propounded in a series of important articles and monographs published by the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions, Santa Barbara, California; see especially, Ferry’s “Caught On the Horn of Plenty,” “Jobs, Machines, and People” by Helstein, Piel, and Theobald, and John Wilkinson’s “The Quantitative Society.” For a persuasive response to some of the basic errors made by our revolutionaries, see George Reisman’s “The Triple Revolution: The Revolt Against the Mind,” Verdict, Oct. 1964. ↩︎

- E. Borne and F. Henry, A Philosophy of Work (New York: 1938), p. 146. ↩︎

- “Further Reflections on the Triple Revolution,” Staff Paper, Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions, Sept. 14, 1964. It is of course possible to define “scarcity” as shortages, insufficiency, and dire poverty (all of which have nearly disappeared in the United States), and to define “abundance” as the contrary of scarcity. And, no doubt, our Revolutionaries do sometimes use “scarcity” and “abundance” in this sense. But it is important to note that none of the predicted consequences of automation follow if the words are used in this sense. (I had not realized it was so easy to confuse “scarcity’’ in the economic and in the poverty, etc. senses until I happened across A. Edel’s Method in Ethical Theory [Ch. 12, “Scarcity and Abundance in Ethical Theory”]: “For if they do these things in a green tree, what shall he done in the dry?”) ↩︎

- “Self-Regulation,” Scientific American, 1955. G. P. Shultz and G. B. Baldwin, in their Automation: A New Dimension of Old Problems (Washington, D.C.: Public Affairs Press, 1955) shed additional light on the novelty of automation: “How does automation differ from other forms of technological change? . . . Most forms of technological change . . . are specific to a single industry in their application. Automation . . . stands for a generalized form of technological change, one potentially applicable over a wide range of manual and white collar operations in a great many industries. In this sense, it promises to have an impact like that of mass production . . . True enough, it is primarily a technological development. But in a more abstract sense it consists of a new way of thinking about the total conduct of a business. . . . The key to this new perspective is flow or continuous process, in contrast to intermittent or stop-and-go methods. . . . Automation is basically a technological development which allows us to realize this flow principle more perfectly.” ↩︎

- “Economic Institutions and Democracy,” published by The Society for Democratic Integration in Industry, London (n.d.), italics mine. ↩︎

- “Automation,” American Enterprise Institute, March, 1963, pp. 4–5. ↩︎

- Alchian and Allen (Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth, 1964), p. 474. ↩︎

- “The Great Unemployment Fallacy,” Sept. 5, 1964. Dale believes that the solution to our unemployment problem lies in stimulating aggregate demand; but for evidence and argument to the contrary, see H. Demsetz, “Structural Unemployment: A Reconsideration of the Evidence and the Theory,” Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. IV, 1961, pp. 80–92, where Demsetz effectively defends, against the aggregate demand position, the thesis that “minimum wage laws and union wage rates make it impossible or difficult for a growing component of our labor force to offer its services at wage rates sufficiently low to be employed.” Let me, in order to illustrate part of Demsetz’s thesis, cite the classical example of the elevator boys in Chicago. A few years ago elevator boys in downtown Chicago were earning $1–$1.25 per hour. Then they were organized, and their wages rose to $2.40 per hour. But automatic elevators could be bought and maintained at a cost of approximately $7,000 per year. Now at the old rate of pay, two shifts of elevator boys cost about $5,000 per year; at the new rate, it was cheaper to introduce automatic elevators, and the elevator boys were disemployed. But notice: there was a time lag between the introduction of the new, higher rate of pay and the introduction of the new elevators—for 6, 9, 12 months the boys were making highly satisfactory wages. Then the new elevators were introduced. And to what did the boys (and the union) attribute their lost jobs? To automation. Not to the rise in wages above market level. It goes without saying that one concerned with the problems of juvenile delinquency would find it hard to approve this sort of union activity (or the raising of minimum wage rates above market level). Cf. “The Real News About Automation,” C. E. Silberman, Fortune, January, 1965. ↩︎

- I am grateful to Mr. Ferry for making available to me his files of newspaper and magazine clippings, and his recent unpublished writings on this topic. ↩︎

- New York Times Magazine, October 11, 1964. Cf. Capitalism and Freedom (Chicago: 1962), Chs. 11, 12. For an excellent analysis of the nature and extent of poverty in the United States, and for a critique of the analysis on which the War Against Poverty is based, see Rose Friedman’s Poverty: Definition and Perspective, American Enterprise Institute, February, 1965. ↩︎