Not Me: Memoirs of a German Childhood

by Joachim Fest, trans. Martin Chalmers

(London: Atlantic, 2012)

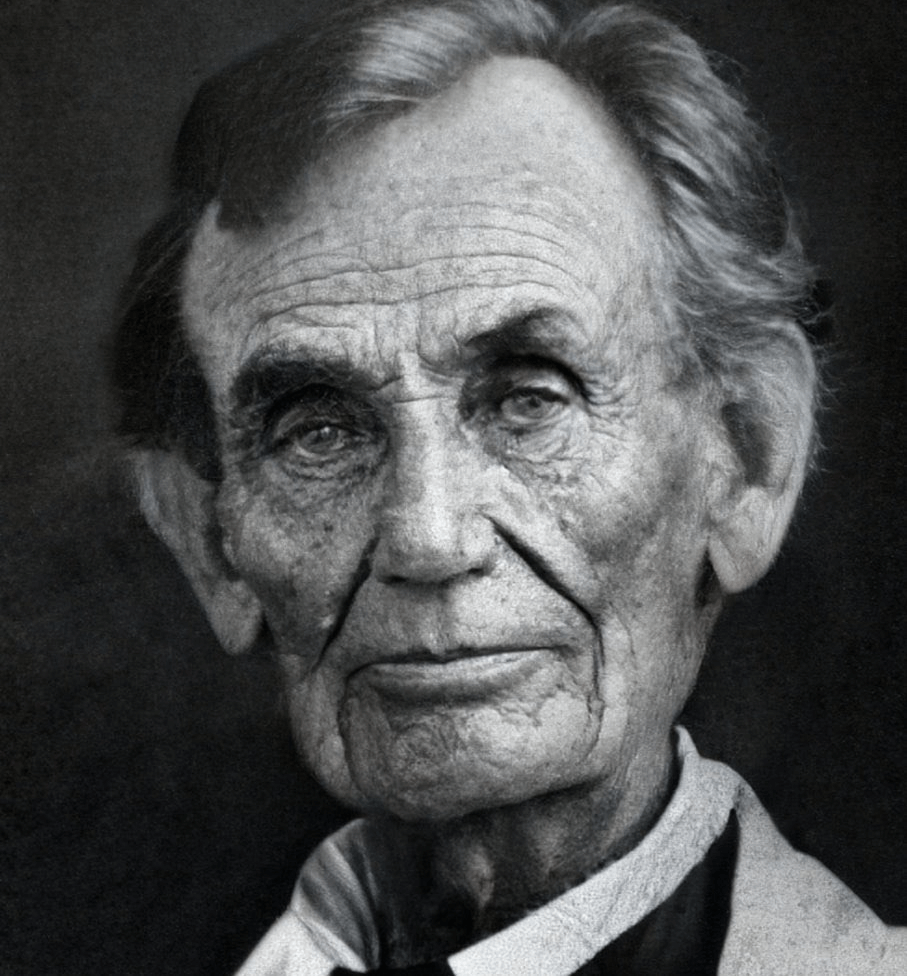

Joachim Fest, who died in 2006, was a kind of public intellectual much more common in Europe than in the United States. Beginning as a radio journalist in postwar Germany, he rose to one of the top positions in the German journalistic world as an editor of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. He also published a series of bestselling historical books and essays on the Nazi period. Most famous was his monumental 1973 biography of Hitler, which remains influential for relating the dictator’s life to the larger intellectual currents in early-twentieth-century Europe, as well as a biography of Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer, based on interviews the young Fest conducted with Speer in the 1960s. In his later years he also published a series of shorter works, including a historical study of Hitler’s last days, which became the basis for the award-winning film Downfall (Der Untergang).

Never an active partisan, Fest nonetheless became known as a critic of the left-wing dominance of German intellectual life, most publicly during the so-called Historians’ Quarrel (Historikerstreit) in the late 1980s over the uniqueness of the Holocaust. His arguments placed Fest to the right of center, but at the same time he prided himself on his political and intellectual independence. As he puts it: “If asked about my guiding principles, I would always refer to my skepticism and even to my distaste for the spirit of the age and its fellow travelers.” He traces the roots of his “political distrust” back to his father, who taught his children a motto based on a passage from the Gospel of Matthew (26:31) that became a family mantra: “Etiam si omnes ego non—even if all [abandon you], not I” (292). The point of this quotation from Saint Peter is that the most important thing in any crisis was maintaining one’s personal integrity and devotion to first principles, even in the face of overwhelming public pressure.

Drawing on that basic insight, Not Me offers a sympathetic portrait of the traditional German middle-class world and its collapse during the Third Reich. Published in 2006, the year of Fest’s death, this impressionistic biography, now available in a very readable English translation, traces his life from childhood in the comfortable Berlin suburb of Karlshorst through school days in Berlin and Freiburg, his service in the Wehrmacht during the last year of the war, and subsequent experiences as a POW, concluding with reflections on the postwar world. Fest clearly has great affection for the world that produced him, solidly bürgerlich (a much less pejorative term in its German usage than the French import bourgeois is in English)—learned, devout, and patriotic. At the same time, he saw that this world carried within it the seeds of its own destruction. “Seen as a whole,” Fest writes, “what I had experienced was the collapse of the bourgeois world, a world of civic responsibility. Its end was already foreseeable before Hitler came on the scene. . . . What survived the years of his rule with integrity were solely individual characters—no classes, groups, or ideologies” (281).

Both Fest’s affection for that lost world and his critical autopsy of it focus on one particular character with integrity—his father, Johannes. Fest senior was a pillar of the traditional Berlin Bildungsbürgertum. Although a Catholic, which made him part of a sometimes embattled minority, Johannes Fest was in many ways a stereotypical Prussian schoolmaster and paterfamilias—strict, devoted to duty, and serious about the power of learning. He raised his family to revere the classics of German culture and to cultivate serous conversations on art, literature, and music. A strong supporter of the Catholic Centre Party, he was anti-Nazi and pro-republic, skeptical of utopianism of all kinds. Even as the republic collapsed, he clung to a deep Prussian and German patriotism.

Those qualities served him when the Nazis came to power. Forced from his job and unable to gain any other employment, he remained unbending in his refusal to accommodate himself to the regime. As a result, the family lived in straitened circumstances, dependent on help from friends and relatives. In 1939 a colleague offered him a job as director of a language school. But the authorities intervened, vetoing the appointment but declaring: “As soon as there was evidence before the department that the petitioner had come round to a positive assessment of the National Socialist Order, and of its leader Adolf Hitler, then it would be prepared to review the matter.” His laconic response, after an angry laugh: “The bastards will wait a long time for that” (100). To add insult to injury, Fest senior was drafted into the armed forces in the last year of the war and sent to the Eastern Front. Taken prisoner by the Soviets, he returned from captivity an emaciated shell of his former self, to a family shattered by the war and its aftermath, broken but unbowed.

Fest does not overdraw his portrait. Johannes Fest was no active resistance fighter. His moral courage played out in private (though it cost him in public), but was no less admirable for that. Meeting one of his colleagues on the day he left his school for the last time, in 1933, a colleague asked simply, “Fest old man . . . did it have to be like this?” To which he replied, “Yes, it had to be!” (35). His father’s unbending devotion to his principles clearly impressed Fest, even though he does not hide the tensions this produced within the family. Fest expresses deep sympathy for his devout and devoted mother, whose plans for a comfortable existence were dashed by the criminal regime and her husband’s rigid rectitude. Occasionally frustrated by the elder Fest’s political obstinacy, she bore all silently. She was herself built of stern Prussian stuff. Her watchword was “Just don’t get sentimental!” (77). It was necessary to avoid political discussions in public, Fest told his two oldest boys, but “a state that turns everything into a lie shall not cross our threshold as well. I shall not submit to the reigning mendacity, at least within the family circle” (53). By 1936 they had resolved to have two sittings at dinner—an apolitical meal for the smaller children and a later sitting for the older boys and their parents, where current events were debated. After the war, he had no regrets: “One sometimes has to keep one’s head down, but try not to look shorter as a result” (277).

As his small circle of friends continuously narrowed, Fest’s father remained philosophical. When one friend claimed that it was good that the end of the republic had eliminated “all that ‘political blathering,’” he responded with the observation that “in reality, everyone was simply searching for an excuse to look away from the crimes all around” (42). When a former Centre Party colleague explained that the semilegality of Hitler’s rise to power had made it difficult to organize a formal uprising, he responded ironically that he understood: “As proper Germans, upholding the law was more important to them than right and wrong” (43). When another colleague claimed in 1938 that the Nazis were not monsters and that people should accommodate themselves to the regime, which was more efficient than the republic, he could only sigh at the dinner table: “One more thing that’s incomprehensible . . . Someone who didn’t notice that he was down on the ground. ‘Even when you shout it in his ears’ ”(75).

The elder Fest recognized that some things may have improved in Germany during the first years of the Nazi regime, but the Germans who were untouched by the regime’s brutality “didn’t want to see the means by which Hitler had achieved his successes. They thought he had God on his side; anyone who had retained a bit of sense, however, saw that he was in league with the Devil” (85). He despaired over the continued successes of the regime through 1938, wondering how this fit with his belief in God’s plan. Watching Britain and France appease Hitler was as painful as watching his neighbors give in. Fest’s mother summed it up well with the simple statement: “[We] saw it through, even if to this day I don’t know how we managed it” (51).

There are many riches in this book beyond Johannes Fest’s quiet heroism. Readers interested in early-twentieth-century family life in a European metropolis and the lived experience of dictatorship and war will find much to enjoy. Fest’s story also has other unforgettable characters. In addition to the Mozart-loving priest next door, Father Johannes Winterbrink, there was Dr. Meyer, the family’s elderly and cultured Jewish friend, whom the schoolboy Fest visited regularly for poetry readings and philosophical conversations. Dr. Meyer taught Fest many things, such as the simple maxim, “It is less of a problem for the world if people are stupid than that they have prejudices” (95).

Dr. Meyer did not survive the Holocaust, nor did many other Jewish friends and neighbors. Fest does not avoid this subject. He describes the initial confusion about the disappearances but also leaves no doubt that people such as his father and others willing to face the truth knew the terrible things that were afoot. During the Christmas holidays in 1942, his father told Fest and his brother of atrocities described by the BBC. He followed up on those stories, and Fest leaves no doubt that Germans could and did know quite a bit about the Holocaust even as it happened (165, 175–76).

What made Johannes Fest special was not who he was before the Nazis came to power, but the fact that he, unlike so many exactly like him, stayed the person he was even afterward. After all, even Saint Peter saw his confident declarations collapse into denials at the critical moment. Fest’s admiration for his father sharpens the contrast with others and fed Fest’s subsequent development into a political skeptic. Fest admits that he and his older brother distanced themselves from their parents, as did many of their generation, but with a difference. “Unlike the overwhelming majority of Germans, we were not part of some mass conversion. Whenever talks came round to the 1930s and 1940s, many of our contemporaries felt remorse, but we were excluded from this psychodrama. We had the dubious advantage of remaining exactly who we had always been, and so of once again being the odd ones out” (276).

Although he does not make it explicit, Fest also makes an important argument about the nature of the Nazi regime. For all his and his father’s conservative contempt for the character of leading Nazis (Fest senior complained, “Historians like myself were giving them a historical dignity to which they were not entitled” [287]), Fest does not fall for the fairy tale that the Germans had the Nazis thrust upon them. Part of their dangerous appeal was precisely that comfortable conservative citizens could and did see in them a refuge against the complexities of the interwar world.

One of the most controversial elements of Fest’s Hitler biography draws on this insight. In the opening pages, after describing a failed assassination attempt on Hitler in 1938, Fest speculates that if the attempt had succeeded, many Germans would look back on Hitler as one of Germany’s greatest and most successful leaders. This conclusion flowed from the recognition that, at least in those first years, the Nazis were carrying through a program whose main elements had been embraced by most mainstream political parties. The more one knows about Fest, however, and especially after reading this book, the more one sees that observation as a meditation on the seductive nature of the Nazi program. In his own life he had seen how the Nazis appealed to members of the middle class and the price paid by those who chose to resist the temptation. Noting the crisis of the republic, he remarks that “broad but fickle sections of the population, who were essentially well disposed to the republic, believed themselves to be threatened not only by radicals of the Right and Left, but increasingly surrendered to the idea that nothing less than the spirit of the age was against them. With Hegel in one’s intellectual baggage, one was even more susceptible to such thinking” (279–80).

Johannes Fest blamed other German intellectuals. Thomas Mann, for example, despite his later rejection of Nazism, discredited himself in Fest’s eyes with his Reflections of an Unpolitical Man. “Precisely because it was so well written it had done more to alienate the middle classes from the Republic than Hitler” (98). People who treated the actual politics of the republic with contempt, throwing up their clean hands and refusing to participate, were complicit in both the destruction of the republic and in the horrors that followed. “Too many forces in society had contributed to the destruction of this world, the political Right just as much as the Left. . . . Basically, Hitler had merely swept away the remaining ruins. He was a revolutionary. But because he was capable of lending himself a bourgeois mask, he destroyed the hollow façade of the bourgeoisie with the help of the bourgeoisie itself; the desire to put an end to it all was overpowering” (281).

The perhaps paradoxical message of Not Me is that a healthy society depends on individuals who refuse to compromise their integrity, even if that means standing in opposition to what appears to be the majority opinion. At the same time, it is a reminder that republics die when citizens abandon politics to the unprincipled. In a modern world where politics often appears irredeemably corrupt, and where many are tempted to abandon hope and indulge in blanket statements rejecting the electoral process, Fest’s story is a reminder of the quiet heroism of upright citizens. That heroism produced “a life full of privations” and “for compensation, my father had only the knowledge of meeting his own rigorous principles.” It may not always have been enough, but “it nevertheless provided him with a significant degree of satisfaction” (277).

Not Me is a reminder that citizens need to embrace the responsibilities of citizenship. Not in pursuit of utopias, or in the mere cultivation of private gardens, but in the constant daily struggle against our own weaknesses. That is one collective enterprise that even Johannes Fest would join. ♦

Ronald J. Granieri is the executive director of the Center for the Study of America and the West at the Foreign Policy Research Institute and a contract historian with the Office of the Secretary of Defense.