The New York Times columnist Ross Douthat has been making a career for the past several years arguing that America, and Western civilization more generally, is in a state of decadence, which he defines as “economic stagnation, institutional sclerosis, and cultural repetition at a high stage of wealth and technological proficiency and civilizational development.” Cinema, a cultural form Douthat and I both love, is a perfect example of the decadence he describes. The medium’s technology continues to advance and the amount of money coursing through the movie business continues to grow, but, institutionally and creatively, the movies have been stuck in a rut of cheerless repetition.

The ninety-fifth Academy Awards, recently completed as of this writing, showcased both the illness and what, for some, looks like the cure. The Oscars rarely nominates sequels for Best Picture, but this year two were nominated: Top Gun: Maverick and Avatar: The Way of Water. Not coincidentally, the two films were by far the biggest money-makers of the year, the former earning nearly $1.5 billion at the box office, the latter over $2.3 billion. Between them, they are credited with saving the theatrical experience—and I found both films enjoyable. But both are also fundamentally decadent projects, one a reboot of a camp classic that reaches for greater significance by becoming a metaphoric swan song for the movies themselves, the other the transformation of an idiosyncratic blockbuster movie (built, like Star Wars before it, out of derivative elements) into a mere fragmentary episode of what will no doubt become a sprawling, multi-tentacled franchise like the Harry Potter, Marvel, or Star Wars “universes.”

If Top Gun and Avatar are symptoms of the illness, then Everything Everywhere All At Once—which was the most-awarded film in history prior to Oscar night, and became the first film in history to win six “above the line” Oscars—might look like the cure. An independent film that became a genuine pop-cultural phenomenon, starring mostly genre actors rather than big Hollywood stars, it offers the promise of escape from corporate control of our imaginations. Meanwhile, by blurring the lines between genres (science fiction, martial arts, and family drama) and blending dorm-room philosophy with low comedy, Everything Everywhere All At Once seems to be taking Ezra Pound’s dictum, “make it new,” more seriously than any other film of recent memory. But substantively, as Douthat himself pointed out in predicting its triumph, Everything Everywhere All At Once is itself a spiritual expression of decadence, an attempt to relieve the existential despair prompted by the collapse of narrative with a megadose of pure sentimentality. I’m skeptical how often that trick can be repeated.

As it happens, Pound’s dictum may itself be a mistranslation. The Chinese characters that became “make it new” in Pound’s hand may mean “do it again” or “start back at the beginning,” a call for regeneration and new growth more than to do something entirely novel or unprecedented. In that spirit, what struck me more about the state of movies today was not the battle between the blockbuster reboots and the indie kaleidoscope, but the films that went back to the source. Top Gun and Avatar weren’t the only films nominated for Oscars that were reworkings of predecessors. Three other films—all international productions, none of them aiming for blockbuster status—reached back to classics for inspiration. Whether they were able to make them new in a way that might foster future growth is the question.

The first film version of All Quiet on the Western Front won Best Picture in 1930, only the third year of the Academy Awards’ history. I revisited it in advance of seeing the new film of the same title, the first German film based on the novel, to see whether I would find it dated, in need of a new version to be able to reach contemporary audiences. Stylistically, of course, the film is of its era; the dialogue often has a stagy quality, with characters apt to make speeches, and of course the effects are not as gory as contemporary audiences are used to. Dying is far more decorous in the film than it was in real life or is likely to be in a contemporary treatment of World War I. But it is just as random and indiscriminate, just as bereft of heroism. And the scenes of battle and of bombardment remain thoroughly harrowing. The feeling of being helpless and trapped as a hostile force tries to kill you is as visceral as in any contemporary horror film.

What about the antiwar “message” of the old film? There’s a cliche that there is no such thing as an antiwar film, because film inherently makes war seem exciting, and there’s a lot of truth to that view. But the 1930 All Quiet on the Western Front does about as good a job as could be expected of making war itself seem pointless, wasteful, and unheroic. There are other ways in which an antiwar film can wind up valorizing the experience, though, and one is by giving us a taste of the comradeship of arms. The first All Quiet on the Western Front certainly does this. The friendship that Paul (Lew Ayres) forms with the gruff, working-class Kat (Louis Wolheim) clearly surpasses any relationship he had or could have had in civilian life, something brought home forcefully when Paul goes home and discovers that no one back there has the foggiest idea what he’s been through, and that he’ll never truly accommodate himself back to that life. He longs to go back, not for the excitement of combat but for the fellowship. The movie kills Kat off very shortly after his reunion with Paul, but the audience inevitably feels, along with the sense of pointless waste, a sense of “better to have loved and lost.”

But the old film’s ending performs a reversal of viewers’ sentimental feeling about the death of Kat. While Paul is home on leave, we learn that he and his sister used to catch butterflies as children, and the butterflies are still mounted on the wall of their home. At the end of the film, Paul sees a butterfly, and lifts himself above the protection of his position to reach for it. An enemy sniper spots the motion, and kills him dead with a single shot. Though the moment is brought home in a sentimental fashion, the clear point is that any emotional attachment is a liability in this world of war.

Before I saw it, I had already heard negative things about the new film, directed by Edward Berger, which was nominated for nine Academy Awards, including Best Picture, and won the Oscars for Best International Feature, Best Cinematography, Best Original Score, and Best Production De-sign. But I was still unprepared for just how thoroughly it would upend not only the narrative but the aesthetics and even the point of the earlier film. Right from the beginning, the story diverges profoundly. Whereas the 1930 film (like the novel) begins near the outset of the war, the 2022 film begins in 1917, after the war has already dragged on for nearly three years. We are given no vision of civilian life to contrast with the horrors of war; on the contrary, the home front appears thoroughly infected with the regimentation and brutality of the war effort. Even the patriotic speech of the professor who convinces the students to join up is fundamentally altered. The 1930 version has the professor talking about duty but also individual honor and heroism, values that Paul will learn are meaningless in the trenches. By contrast, the 2022 version has the professor frankly talk about how individuality is meaningless and the point of patriotism is subsumption into the collective. There’s an honesty to this appeal that immediately undermines the narrative of disillusion that is so central to the original.

Perhaps the reason is that this film does not chart a narrative of disillusion. On the contrary: this film charts Paul’s “progress” from weakness to competency to apotheosis as a killing machine. Where the Paul of the 1930 film joined up for idealistic reasons, the 2022 Paul joined up to prove he was tough enough to handle it. And while in the early scenes he is mostly terrified and incompetent, with Kat’s help he learns how to handle himself and survive life on the front. In the end, he is killed not for a moment of sentiment, but after hand-to-hand combat with a nameless enemy, a fight that takes place after the armistice has already been signed (but has not yet gone into effect).

The intention is undoubtedly to highlight the absurdity of the killing—that’s why the new film moves so much of the action to the very end of the war, and why it inserts endless scenes of empty diplomatic wrangling between German and French leaders over the terms of the armistice. There’s no narrative tension here, because we know how the war is going to end, and I’m not sure who comes off worse in this depiction of the leadership of the two warring nations. But I could not help recalling that while the 1930 film gave the common soldiers the dignity of being able to debate what their leaders were up to, the new version implicitly suggests that thinking was always above their pay grade. Since we’re “with” the soldiers, though, and since they have been largely denuded of individual psychology or character, the framing has the opposite effect of what was intended. The final battle becomes an absurd apotheosis, the moment that Paul becomes who he wanted to be at the beginning, an action hero of sorts. He’s still largely anonymous, still little more than a cog, but this is the only nihilistic achievement available to an anonymous cog. Whatever the head registers by way of message, the heart and guts register it as a kind of victory.

This is the other major way a purportedly antiwar film can fail: by turning the protagonist into a nihilistic hero. That’s what happens at the end of Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket. It’s what Robert De Niro’s character explicitly aims for in Michael Cimino’s Deer Hunter, but consciously rejects at the end, leaving the audience bereft of heroes. The new All Quiet on the Western Front doesn’t seem even to be aware of that risk. Nor is it aware of the consequences of aestheticizing the experience of combat—such stunning vistas, so much gorgeous slanted light, so many misty mornings and firelit nights. Even the trenches feel spacious enough to get the desired shots, and even the most hideous corpses are, in their way, beautiful. The heavy-handed score, with its three repeated notes, tells us how ominous the story is supposed to be, but its main effect is to contribute to the dehumanization of the tale, and winds up underscoring less the audience’s dread than its anticipation of some kind of climactic release.

German critics have largely repudiated this version of their sacred text, and I’m tempted to agree with them in ascribing its failures to the baleful influence of video games, Netflix, or America’s infatuation with dystopian action flicks. But I suspect that the deeper problem is that there is no reason for a German to make a movie of Remarque’s novel today. Germany’s current struggle is whether and how to address its deficiencies in self-defense, a topic that has become unavoidable in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Inevitably, any talk of rearmament will bring up the ghosts of the past, but all this film proves is the degree to which those ghosts have become domesticated, and the experience of the war abstract and aestheticized rather than visceral and present. That’s no way to oppose a war, and no way to augur in a necessary return to arms either. A contemporary version of All Quiet on the Western Front might have a better chance of being true to its source material if it were made not in German, but in Russian.

I yield to no one in my enthusiasm for Kazuo Ishiguro, whose novels I have written about in these pages before. When I learned he had penned the script for a remake of the classic Akira Kurosawa film Ikiru, and that the film would star Bill Nighy, I was intrigued in the extreme—but also a bit surprised. Ikiru is a 1952 film that treats some very familiar Ishiguro themes, of service and the meaning of an individual embedded in a larger social system of a dubiously ethical nature. But it comes at them very differently from how Ishiguro usually has done. Kurosawa, with Ikiru, had transplanted Tolstoyan ideas onto Japanese soil. I was curious to see whether a further transplant, to postwar Britain, might take when effected by Ishiguro, himself a youthful transplant from Japan who has always observed the culture of his home country through a veil of difference.

Ikiru’s hero, Kanji Watanabe (Takashi Shimura) is a municipal bureaucrat, a functionary in a larger system to which he has dedicated his life. That system, though, is dedicated first and foremost to stasis, its functionaries far more concerned with their positions within it than with the people whom it is intended to serve. We first encounter this system’s resistance to any activity as a group of poor women beg Watanabe’s section of the bureaucracy to help them. Their out-of-the-way corner of the city has an empty lot with poor drainage that has filled with raw sewage; they want the area cleaned up and turned into a playground for children. Instead of helping them, Watanabe tells them to try their luck in another department; when they return, he takes their request and files it away, where it will never be dealt with.

Then Watanabe learns that he has terminal stomach cancer. He learns it by surprise—his doctor had been planning to hide his condition from him, because what would be the point of ruining his final months of life with a death sentence? Another patient, however, warns him that a reassuring diagnosis requiring little treatment is the worst possible sign. Watanabe knows, suddenly, that he will soon die, and he is struck immediately by the realization that he has wasted his entire life, has never truly lived.

He sets off, then, to try to learn how to live. First he meets a poet, a proto-beat, in a bar where Watanabe is trying to drink himself into a stupor. The poet determines to show Watanabe what life is really about, taking him drinking, gaming, dancing, and to a hostess bar where he can find female companionship. But Watanabe wanders through this hellscape of amusement with a desperate look on his face. Even when he is seated in the hostess bar, he can only sing a sad, sweet song from his youth that breaks the mood of forced merriment. He is not distracted. He knows he is still not living.

Next, he latches on to a young member of his department, a girl who has been chronically dissatisfied with its pointless busywork. He asks to take her out, making no sexual advances, only wanting to enjoy the company of someone who seems so alive. She pities him, and enjoys seeing that he has another side than the walking dead man she had taken him to be. Watanabe’s son and daughter-in-law, with whom his relationship has been distant at best for years, discover what they take to be his dalliance, and confront him about it, which drives a stake through the heart of what remains of their relationship. But friendship with a young woman does not turn out to be the catalyst for Watanabe’s new lease on life; on the contrary, she finds his presence increasingly disturbing, and when he reveals his medical situation, and his consequent desperation, she recoils from him.

She does prove the catalyst in another way, however. By this point in the film, she has left her job in the bureaucracy and become a factory worker, making toys. The work is much more difficult, much more tiring, but it has meaning for her in a way that the paper-pushing never did, in that she can imagine all the children who will find joy playing with the toys she makes. This is what leads to Watanabe’s epiphany, as he decides how he will spend the rest of his life meaningfully.

In an extraordinary structural decision, the film then flashes forward to Watanabe’s funeral and wake, where his family and colleagues have gathered to pay their respects, and unravel the mystery of Watanabe’s last months of life, which were so different from all that came before. Over the course of the wake, it becomes clear that Watanabe devoted the rest of his life to assisting the ladies with the sewage-logged plot to get their playground. Initially, the various bureaucrats at the wake are unwilling to attribute the achievement to Watanabe; everyone wants a bit of credit for the accomplishment, and no one wants to acknowledge that it would never have happened had not Watanabe behaved in a very out-of-the-ordinary way. Once their consciences force them to admit his crucial importance, they struggle to understand why he did it, only slowly coming to the conclusion that he must have known he was dying.

The bureaucrats, quite drunk by this point, swear to uphold the principles of honorable service that Watanabe showed them—only to betray that promise the very next day in their sobriety. The final shot of the film shows Watanabe, days before his death, singing the same sad, sweet song as he sits on a swing in the snow on the playground he built, heedless of the fact that he is likely killing himself being out in the cold in his condition, because this is what he lived for.

It’s a deeply beautiful film, often compared, and justly, to It’s a Wonderful Life in both its structural innovation and its blend of deep melancholy with the redeeming light of hope. And while it was inspired by Tolstoy’s Death of Ivan Ilyich, the Japanese setting transforms the story profoundly in two key ways. First, the film was made in postwar Japan; the bureaucracy in which Watanabe is embedded had only a few years before served Japan’s fascist military dictatorship. When we see, in flashback, Watanabe’s son going off to war, it is to fight for the Emperor in China or southeast Asia. That he came back at all is notable; that Watanabe spent much of his life simply keeping his head down is, by contrast, the most unsurprising thing of all.

Second, and relatedly, the way Watanabe achieves his goal of a meaningful life is not merely through persistence, but through the complete abandonment of the requisites of personal honor. He begs; he pleads; he abases himself shamelessly; he makes himself an embarrassment, and when asked how he can smile at people who treat him with contempt, explains that he doesn’t have time to have any enemies. Watanabe’s behavior is not merely a revolt against bureaucratic norms; it is a revolt against the hierarchical fabric of Japanese society as a whole. Ikiru is a fable that transcends time and place, but in its original time and place it was a far more radical broadside against its society, pointing to the need for a profound spiritual transformation as the key to national rebuilding.

These, I thought, were the very threads Ishiguro would surely grasp in rethinking the film for the remake. His breakout novel, The Remains of the Day, is set in the same period (though much of the action takes place in flashback to the 1930s, the period with which the protagonist is reckoning), and the novel ends on a note of epiphany of wasted life and necessary transformation very like where Ikiru begins. How disappointed I was, then, that he did precisely the opposite. If Ikiru is a subtle but powerful critique of a society facing the need for great change, Living is a nostalgia piece, its mild critique of British reserve long since assimilated to conventional wisdom, and more interested in any event in lionizing its purported virtues instead.

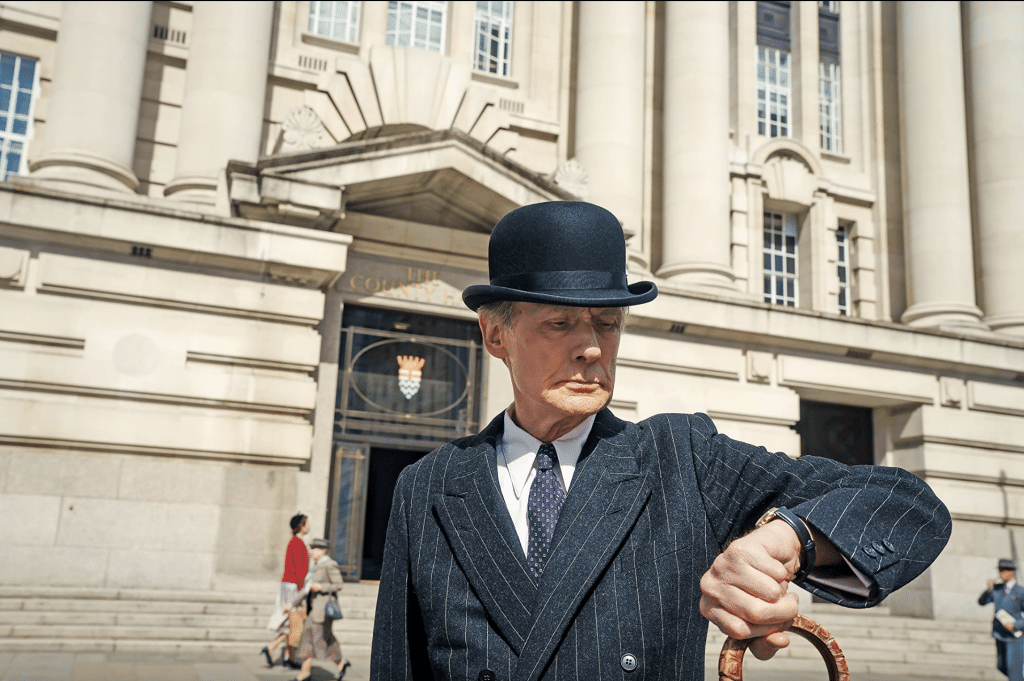

The film follows Kurosawa’s original plan, down to the time period, which is now postwar London. But the film labors to protect its hero, Williams (Bill Nighy) from the strain of spiritual transformation, and this completely alters the tone and meaning of the film. Unlike Watanabe, Williams learns of his diagnosis from his doctor, and takes the news with proper stiff-upper-lip British stoicism. Instead of going to a bar to drink himself into a stupor, he meets his poet in a pleasant seaside resort cafe. He certainly gets tired out following his guide on his tour of the world’s amusements, but he betrays no sign of desperation. And far from being treated as an out-of-place intrusion, he is welcomed everywhere he goes.

Similarly with the relationship he establishes with his young colleague. They go on their little outings, and she is clearly charmed by him, and him by her. When she begins to fret that people may talk, seeing them together, she is pained to reassure him that she doesn’t think he had any untoward intentions—and he is pained to spare her the embarrassment of gossip. He reveals his illness, and his desire to figure out how to be alive, as she is, and, far from repelling her, this brings a sentimental tear to her eye. She herself has not changed the bureaucracy for the factory, but instead for waiting tables, which she had expected to be a managerial position, so there’s no opportunity for her experience to trigger an epiphany. So the epiphany comes without a trigger: Nighy simply rises, goes back to the office, and launches upon his plan with a little smile on his face.

The effect of all of this is to turn the protagonist from a desperate man in search of spiritual conversion into a sweet but befuddled fellow who just needs to see where his duty really lies to buckle down and do it while there is still time. He is, in other words, an exemplar of quiet virtues that we identify with the Britain of the postwar period, and the mission of the film seems to be to convert us back to them.

Nostalgia, though, cannot achieve that end because it is not an encounter with the real past. Living’s director, Oliver Hermanus, has said that he wanted the film to be a love letter to British films of the period. But when I think of postwar British films that have stood the test of time I remember their ironic relation to stereotypical Britishness, as in the Ealing Studios comedies like Kind Hearts and Coronets; or a quietly desperate grappling with the emotional consequences of repression, as in a film like Brief Encounter (which, to be fair, isn’t quite postwar); or the transplanted noir of Night and the City. Those films were, indeed, living. Hermanus’s remake, though it won Oscar nominations for both Ishiguro (for Best Adapted Screenplay) and Nighy (for Best Actor), sadly feels more like a dead sentiment walking.

My final pairing does not technically involve a remake. Nonetheless, EO, a Polish film directed by Jerzy Skolimowski which was nominated for the Oscar Best International Feature, was quite plainly inspired by Robert Bresson’s 1966 classic, Au Hasard Balthazar. Both Bresson’s and Skolimowski’s films tell the story of a poor abused donkey on a picaresque journey through a brutal human world. But the comparison ends there. Where Bresson’s film reaches for a profound spiritual insight (as Kurosawa was inspired by Tolstoy, Bresson was inspired by Dostoevsky’s novel The Idiot), Skolimowski’s explicitly rejects ascribing any meaning to the suffering its protagonist endures.

Au Hasard Balthazar is a difficult movie to watch and to fully understand. It begins in a kind of pseudo-Eden: a young donkey living on a farm near the Pyrenees is removed from his mother to become a pet and plaything of a man’s children, who literally baptize him and give him his name. His life with them is idyllic, but fated not to last; when one of the children dies, her family leaves the country, and they give Balthazar to the one local girl, Marie, who had become attached to the bereaved father’s young son. She doesn’t keep him long, though, as her father soon sends him off to work for local farmhands.

From this point and over the course of the rest of Balthazar’s life, the girl’s and the donkey’s lives will repeatedly intersect, and parallel, to an extent, in their suffering. Balthazar escapes the farm after an accident and returns to Marie, now a teenager (played by Anne Wiazemsky). She takes him back, but her home life is troubled; her father is feuding with the donkey’s first owner over property, and treats the man’s son, Jacques, who has loved Marie since his childhood and still loves, with contempt. Marie’s father sends Balthazar away to work for Gérard, a local thug whose legitimate job is delivering bread for a bakery but who moonlights in robbery and smuggling. Marie is threatened and then seduced or raped by Gérard, and then falls into an ongoing abusive relationship with him from which she cannot, or does not wish to, extricate herself.

Subsequently, Balthazar is put to work for a drunkard, Arnold, who leads tourists through the mountains on Balthazar’s back; he joins a circus, where he performs feats of arithmetic; he is bought by a miller who plans to work him to death. The film is episodic; each episode and each major human figure represents a different human vice or sin. Marie’s father lets his pride destroy his relationships with everyone he loves; the miller is greedy, exploiting Balthazar and using his money to try to extort sexual favors from Marie; Arnold is gluttonous, ultimately dying when, after inheriting a small fortune from an uncle, he throws a wild party, then falls off Balthazar in a drunken stupor and hits his head. The most complex human characters are Marie and Gérard, the latter a creature of pure envy, wrecking Arnold’s party in rage that he should have inherited wealth and ruining Marie out of sheer malice because of her beauty and kindness, the former perversely attached to him even as he repeatedly abuses her, and rejecting the repeatedly offered love from her childhood sweetheart, Jacques.

If the humans are tortured by their sins and the sins of others, however, Balthazar is something else. He harms no one, but suffers largely in silence. Marie’s mother calls him a saint, and perhaps that is what he is meant to be. His death is certainly evocative. Gérard employs him to smuggle contraband over the border, then flees when spotted by a patrol, which shoots Balthazar; the donkey wanders the mountains until the next day, when he finds a flock of sheep, lies down in their midst, and quietly expires. This is not long after Marie’s father dies, and the contrast is profound. On his deathbed, Marie’s father is visited by a priest, who tells him to forgive Gérard for raping his daughter, assuring him that because he has suffered he is assured a place in heaven, and now he must forgive so that Gérard has a chance as well. Marie’s father replies: “Perhaps I suffer less than you think,” and turns away. The next thing we know, Balthazar is carrying his ashes on his back.

Bresson clearly intends us to find something deeply meaningful in the spectacle of suffering taken on willingly. Whether that meaning “plays” for a contemporary audience is another matter. But if you expurgate it, and leave only the spectacle of suffering, what are you left with? That seems to be the question EO wants to ask, and its answer is not particularly edifying.

EO, like Balthazar, is a donkey, and the protagonist of his story. Where Balthazar’s name has rich associations, EO is simply the sound the donkey makes. His story begins at the circus, where he is tended to by a beautiful girl, Kasandra (played by Sandra Drzymalska), who dotes on him, and who loves a man we are to assume is disreputable because he rides a motorcycle. Animal rights activists get the circus shut down, with the result that EO is left unemployed. So he is sent to a horse stable to work, and on the way he watches horses running free. At a stable, he kicks down a case of trophies the horses have won. Later, he is sent to a farm, where he refuses to work. Kasandra visits him there and feeds him, which prompts him to escape the farm and run after her. But he cannot find her. Instead he wanders through the woods at night, hearing other animals, and the human hunters who shoot at them, coming at one point upon the bleeding corpse of a wolf.

In the most darkly humorous escapade of EO’s life, he happens upon a local soccer game and is adopted by the fans for one team. He brays at a key moment in the action, enabling “his” team to win, and the fellows take him out drinking afterwards. But the humor is only a prelude to more violence. Supporters of the other team attack the pub where the winners are celebrating, smash the place up, and beat EO nearly to death. He is taken to an animal hospital, where a vet tries to save him, and an orderly asks why he bothers.

EO’s miseries continue. Subsequently, he is taken to work at a fur factory, where he kicks the man responsible for killing the caged foxes; later, he is loaded with other animals on a truck whose driver, after trying to seduce a woman by offering her food for sex, gets his throat slit. In his final outing, he’s brought by a wayward priest, who treats him kindly, back to the priest’s aristocratic stepmother’s home. We see the humans argue, the stepmother smash crockery, the priest perform a private communion service; even when there is no explicit brutality, emotional brutality is still present. EO wanders the grounds, then wanders off. EO’s death finally comes when he wanders into a slaughterhouse with a herd of cattle, and in the darkness we hear a bolt pistol fire.

What does this sequence of events mean? It seems to be a mere litany of cruelty, a kind of brief against humanity. But EO is not only not a passive sufferer; he is actively indignant at his place in this cruel world. He doesn’t just envy the horses their freedom; he envies their achievement and kicks over their trophies (or perhaps he is simply disgusted that the trophies belong to their human owners). He doesn’t just observe the killing of the foxes; he kicks the man responsible, possibly killing him. EO has relatively little power in this world, but he resents that fact, and we, as his partisans, are clearly intended to wish that he had more, not only so that he could escape his fate but so that all the other abused animals could as well.

But is this indignation by proxy efficacious? I cannot help but be skeptical. I came out of Au Hasard Balthazar wrestling uncomfortably with its implications; its message is hard, but the human beings it depicted were all recognizable, all suffering themselves, and if Balthazar’s patience seemed incomprehensible, well, maybe that’s because he is a saint, and I am not. By contrast, I came out of EO feeling irritated at its unremitting bleakness about human nature and the possibility of living meaningfully in a cruel world.

When EO wanders through the woods at night, the scene, with its moonlit river and silhouetted figure, is strongly reminiscent of the scene in The Night of the Hunter where the children flee Robert Mitchum’s Harry Powell by night along the water, and he hunts them on horseback. Powell of course was a twisted con artist presenting himself as a man of God in order to abuse and exploit people. I can’t help but think that there’s an allusion to what Skolimowski thinks of Bresson’s film and of its message. If that’s the case, then EO is not an homage at all, and the Polish director shares a bit of kinship with his enviously indignant protagonist, a donkey who kicks over the trophies of racehorses.

Noah Millman is theater and film critic for Modern Age.