In attempting to assess the career of the American director Sam Peckinpah, the centenary of whose birth falls on February 21, 2025, the film critic Rick Moody, writing in Britain’s Guardian newspaper, got no further than the opening sequence of Peckinpah’s notorious anti-Western The Wild Bunch before waxing rhapsodic.

The initial scene, Moody writes, in which the outlaw gang enters town and attempts to rob a railroad,

is noteworthy for the way it juxtaposes its theme music and its incipient outlaw bloodlust with a scene of local children pitting two scorpions against an army of fire ants. In this way is innocence ruined, the title sequence seems to say, after which it reenacts this Nietzschean material, in the course of the film, again and again. . . . The west was like this, Peckinpah says, whether wittingly or unwittingly. It was not so much a place of honour as it was a place where life was cheap, where no one gave a second thought to the man standing next to him. . . . During the Vietnam years (the years in which Peckinpah operated at the peak of his abilities), the squeaky-clean western, the John Ford western, needed to give way to something far more jaundiced; a western that was more about survival of the fittest, and the will to power, and the corruption of the rugged individualist.

Leaving that—and, in particular, the idea that a film like John Ford’s 1956 The Searchers could be dismissed as a hopelessly outdated case of western mythologizing—aside, there is the curious matter in the same Wild Bunch’s opening credits of the positioning of the cast members’ names in relation to the movie’s animal population. The actor Robert Ryan, a highly estimable performer in his way, if not one generally considered a martyr to modesty, had long maintained that he, rather than the likes of William Holden or Ernest Borgnine, should receive top billing in the film. In time, Ryan’s protests on the subject so irritated Peckinpah that the director decided a small retaliation might be in order. As a result, observant viewers may notice that while they are treated to close-ups of both Holden and Borgnine while their names appear on screen, the camera by contrast lingers on several horses’ rear ends when it comes time for Ryan to be so listed.

Somewhere in that brief opening scene of Peckinpah’s most celebrated film, running from the scorpions’ death struggle with the fire ants to the title sequence introducing his cast, there surely lies a point about the director’s essential duality. Was he a high-minded auteur who brought an extraordinary lyricism to a body of work whose characters often convey an undertow of yearning for an earlier, more innocent time? Elegiac pictures such as 1970’s Ballad of Cable Hogue, and the following year’s Junior Bonner, seem to suggest that he was. Or was he a tequila-fueled prankster, to use the most measured word possible, known equally for his lowbrow humor and lifelong willingness to antagonize the likes of censors, producers, studio bosses, and his own cast and crew members, and who gloried in the sobriquet “Bloody Sam”?

Perhaps that was the essence of all fourteen of Peckinpah’s theatrical feature films: their absolute refusal to truckle or compromise, their unflinching reverence for the truth as he saw it.

The answer to the question seems to be that Peckinpah was a bit of both. I’m always reminded in this context of the time I interviewed the actor Don Gordon for a book I was writing about his friend Steve McQueen. Gordon and McQueen had been sitting together in a Los Angeles diner one day in the early 1970s when they noticed that someone had left a copy of that week’s Hollywood Reporter lying on the counter. As Gordon recounted, “Steve picked it up, tapped his finger at a story with the headline ‘Peckinpah Is Back’ and then sighed and said: ‘Yeah, but which one?’”

Perhaps we should get the “Bloody Sam” persona out of the way first. Somehow when we think of Peckinpah our minds always turn to The Wild Bunch, arguably the first Western to go full bore in its reappraisal of frontier narratives with an accumulating body count in the hundreds and its notorious prolonged slow-motion shoot-outs. Or for its fusion of violence and sheer voyeurism, there’s 1974’s Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, a picture which never misses the chance to treat a woman badly, where bared breasts are the rule and normal décor the exception, and whose reviews at the time of its release went beyond dislike into something approaching revulsion, with descriptions like grotesque, sadistic, horrific, and obscene the consensus. Or for that matter there was The Getaway (1972), whose plot found a husband-and-wife gang, played by the real-life couple Steve McQueen and Ali MacGraw, masterminding a bank heist, with added sex, infidelity, betrayal, and a climactic shoot-out that made Bonnie and Clyde look like My Fair Lady: literally rivers of blood.

But all this, impressively sanguinary as it was, would pale by comparison to the truly jarring scene in 1971’s Straw Dogs in which a character played by the young actress Susan George was subjected to a graphic rape. “I did zoom along in the script to find out where I had to take my clothes off, and saw that this was quite different from any script I had ever read before,” George remarked, a notable understatement to describe a film that the British censors banned in its uncut version for the next thirty years.

Curiously enough, all these actors, and many others besides, would continue to express an exasperated affection for their director, whatever indignities he heaped upon them. As James Coburn, veteran of three Peckinpah campaigns, as he called them, once told me, “The thing about Sam was that he forced you to do your best work. He may have been a nasty bastard, but it was all in the name of the film. You didn’t just phone it in. It had to come from some place within you.”

Perhaps that was the essence of all fourteen of Peckinpah’s theatrical feature films: their absolute refusal to truckle or compromise, their unflinching reverence for the truth as he saw it. His protagonists are often men out of time, outlaws or misfits or faded cowboys who can’t accommodate change. Even amidst the violence, there’s an undertow of yearning for an earlier, more innocent time that serves to encapsulate the two sides of the Peckinpah myth. There is the sacred monster (even if some studio heads would quibble with the adjective) and alcoholic tyrant whom one could imagine coming to work dressed in jodhpurs and carrying a riding crop. And there is the surprisingly soft-spoken artist with a disappointed but clear-eyed view of man’s fallen nature, who continued to see the potential nobility in individual human beings even when the fabric of civilization around them had been lost.

This was the side of Peckinpah perhaps best expressed by 1965’s Major Dundee. At its core, it’s a tale about the eponymous Union officer, played by Charlton Heston, who finds himself put in charge of a military prison filled with lowlifes. In time, Dundee leaves the prison in order to lead the search for two young children who have been abducted by a group of Apaches. In true Peckinpah fashion, the movie takes its charge not so much from the pursuit itself but from the internal tension amongst the posse, which includes a leathery, one-armed scout (James Coburn), assorted horse thieves and drunkards, and a group of freed prisoners in a precursor to the plot of The Dirty Dozen two years later. There’s also a bitterly resentful former friend, memorably underplayed by Richard Harris, who it turns out was once a West Point classmate of Dundee. At its core, the movie is about the fractured relationship between two old comrades who have gone in opposite directions as much as it is a straightforward chase story, albeit one with an obsessed, Ahab-like commander to drive it forward.

He should be remembered for being fearless, if also reckless, in his single-minded pursuit of what he thought his evolving craft required.

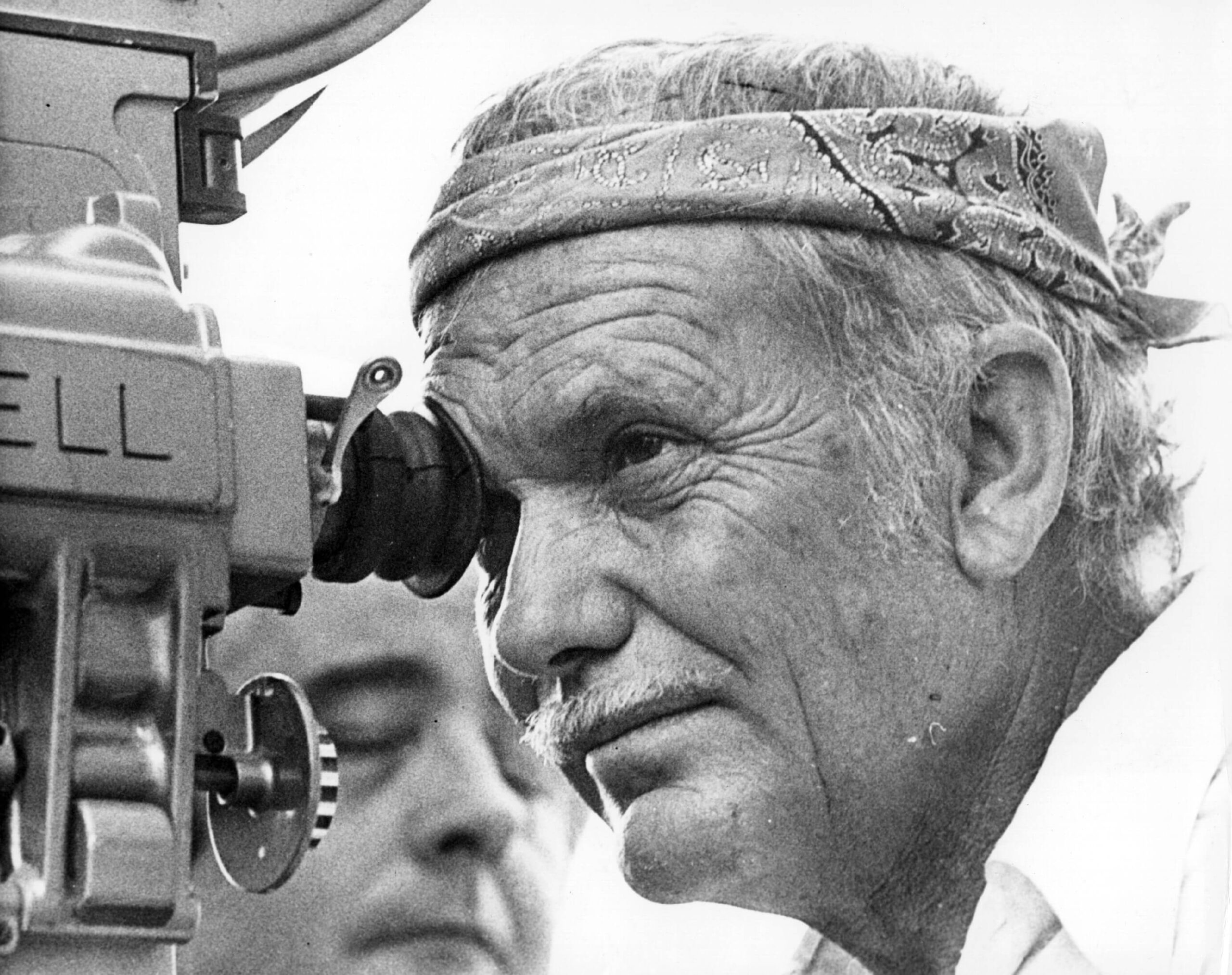

Set against the movie’s higher vision there was on-set strife that rivaled anything on the screen. Major Dundee was a deeply troubled project from the outset. The studio involved, Columbia, slashed the budget by a third days before shooting began. The script was never completed. Within a week, the studio tried to sack Peckinpah. Charlton Heston once told me that “Sam was hard to be friends with on set,” and that in his measured assessment “it was difficult to fully relax with a director who typically turned up for work wearing a bandana and a duster coat, with a bottle of tequila clamped in his hand. People knew to keep their distance.” It soon became one of those nightmarish projects where the filming process itself was a war zone, not far removed from the brutal conflict it portrayed. Nonetheless, Heston, who deferred his salary to get the picture made, stood by the director. “I recognized a creative artist when I saw one,” he added. Columbia eventually wreaked its revenge by cutting the film’s running length from four hours to just two. In 2005, the same studio released an “expanded” version of Major Dundee, including several restored scenes, twenty-one years too late for Peckinpah himself to enjoy his artistic vindication.

For all the excesses associated with “Bloody Sam” and the tragic gunslingers of The Wild Bunch, there’s a strain of romanticism, of old-fashioned chivalry and integrity, to many of Peckinpah’s characters. Perhaps the line that best sums up this essential vein of decency comes in 1962’s Ride the High Country, when Steve Judd, an aging lawman portrayed by Joel McCrea, tells his friend Gil Westrum, played by Randolph Scott in his final screen role, “All I want is to enter my house justified.” The line stands as an article of faith about the need to remain true to a guiding vision, and it was one Peckinpah frequently used in relation to his own life. As James Coburn said, “Sam could be a monster, but he was also a genius at least five or six hours a day, sometimes more, depending on how much he was drinking.” Coburn was one of the scores of actors and technicians who would look back on their working relationship with the monster-genius in question with a kind of wistful affection. “Sam’s real tragedy was the sheer amount of his time and energy he spent on fighting with studio executives, a class of person he ranked only slightly above child molesters, instead of working to get his vision on the screen.”

Lest the point not already have been made, Sam Peckinpah was not necessarily the sort of individual to do things the easy way, nor to invariably follow the conventional career path. There are directors whose last film is very like their first. Having learned their trade and mastered it once and for all, they practice it with little variation to the bitter end. Peckinpah was not quite like that. He should be remembered for being fearless, if also reckless, in his single-minded pursuit of what he thought his evolving craft required. That restlessness took him from the artistic pinnacles of Major Dundee and The Wild Bunch to the indignity of shooting the MTV video for Julian Lennon’s forgettable song “Too Late for Goodbyes,” an especially poignant title in light of the fact that the commission—which came with a $10,000 payday—proved to be Peckinpah’s final directorial effort; he died almost the moment he completed it, of heart failure, in December 1984. He was still two months short of what would have been his sixtieth birthday.

At his best, Sam Peckinpah was a superbly vivid storyteller with a keen grasp of the frailties and contradictions of the human condition. Several of his films pushed technical limits for their times and developed techniques for visual narration. His work pioneered the use of multi-camera filming and montage editing, quite apart from the famous slow-motion sequences that can seem almost suspended in time, like the terrifyingly paralyzed moments of a bad dream. It’s impossible to say with any certainty whether at the end of his life he felt he was entering his house justified. Perhaps the central enigma about this peculiarly American artist is whether he used violence to illustrate larger truths about man’s fallen nature, set alongside his capacity for redeeming moments of grace, or whether he just enjoyed the spectacle. It’s a question that has never been decisively answered, which is one reason why his films still make such compelling, and sometimes unsettling, viewing today.