We organize our history according to key dates, which seem to mark sharp boundaries in the flow of events. The year 1865 is an obvious American example, and 1945 plays a similar role for much of the world. These are the moments when crucial historical trends self-evidently ended or began, and we naturally choose them to frame our books or our television documentaries. When, as so often happens, history refuses to be so precisely framed, we glide over the inconsistencies. Neatness is all.

In the history of Christianity, and of the civilization built upon it, the year AD 325 represents one such natural division. May 2025 marks the 1,700th anniversary of what we usually think of as one of the most decisive moments in that history, namely the great council that the emperor Constantine called at Nicaea, near his new city of Constantinople. Of the pivotal importance of the event there seems little doubt. We speak of the church’s earliest days in terms of Ante-Nicene Christianity, or the age of the Ante-Nicene Fathers. Something, surely, must have changed at that point. But exactly what that might have been remains a matter of intense debate.

The story of Nicaea is quickly told. In 312, Constantine consolidated power in the Roman Empire and granted toleration to Christianity the following year. He accepted some leading Christians as his advisors on religious matters and felt the need to demonstrate his leadership of the larger church when it fell into crisis or division.

Such a situation developed in Alexandria, where the presbyter Arius argued that Christ the Son was not fully equal to God the Father. Because the Father was unique in being unbegotten, he must be different from the Son, who was begotten in time, and through whom the Father created the world: “There was a time when He [the Son] was not.” Just how directly these ideas stemmed from any one individual such as Arius is much disputed, but it is rhetorically useful to label any given teaching as the quirky sentiments of one lone individual, rather than a broad intellectual current. It should be noted, though, that Arius was actually not departing too far from views held by eminently respectable earlier thinkers.

Even so, as the Alexandrian church debated the issue, it was Arius personally who attracted the stigma for venturing on dangerous ground, and he was condemned. To resolve the spreading controversy, Constantine summoned a great council from the whole world, the oikou mene, which thus became the church’s first “ecumenical” council.

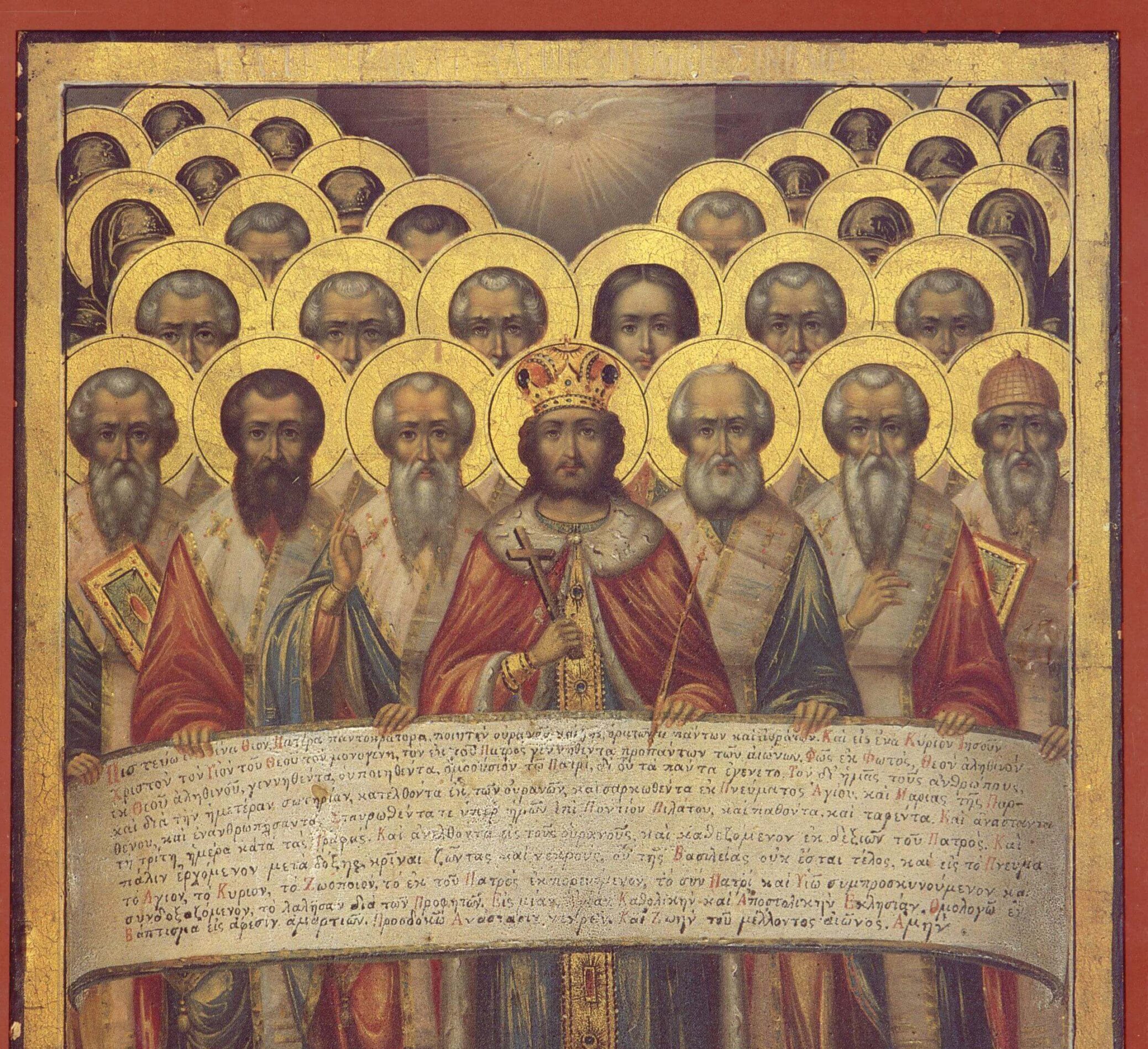

Between 250 and 300 bishops gathered at Nicaea, representing a minority of the 1,800 or so who then held that office; only five came from the Western church. Tensions ran high during the month or so of debate, and legend holds that Arius was publicly slapped by Bishop Nicholas of Myra—the historical original of Santa Claus. Ultimately, Arius was condemned, with only two bishops prepared to speak up for him. Christ’s full equality with the Father was proclaimed in a new creed, which declared him to be of the same substance, homoousion.

With their mission duly accomplished, the Fathers dispersed to their homes, and every one, we assume, lived orthodox-ly ever after.

That history seems straightforward, and far too much so for many tastes. Through the centuries, Nicaea has become a potent symbol of whatever later believers wished to find: it offers a splendid hook on which to hang whatever trends or facts need to be stigmatized.

As a target for liberal or anticlerical sentiment, Nicaea is only too tempting. This was one of the first public manifestations of the intimate alliance between an emperor and the emerging (all-male) church hierarchy, with the goal of telling ordinary Christians what they must believe. It was a charter event in the foundation of Christendom. In plenty of recent writing, the council symbolizes the transition from an effervescent early age of spiritual experiment and gender equality to the hierarchical and patriarchal church of the Middle Ages. It represents the last gasp of expiring freedom before the dark times—before the empire.

At least since the Enlightenment, a great many liberal believers have been fascinated by the thoroughly human Jesus they find in the Gospels, whom they believe is concealed behind the supernatural figure of Christ, the Son of God. Nicaea represents the turning point in understanding the supposed transition from human to divine. To borrow the title of a fine book by Richard Rubenstein, this was When Jesus Became God. Other authors suggest the deeper agendas underlying this shift. It is often said that the newly favored church had everything to gain by becoming an ideological reflection of the empire, the rulers of which had been deified. From that perspective, it made wonderful political sense to elevate Christ to full deity, as a counterpart of the godly emperor on Earth.

For a whole modern generation, the “real history” of Nicaea was expounded at great length in Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code, which borrows from a couple of centuries’ secularist critiques of Christian orthodoxy, strongly flavored with anti-Catholicism. Brown’s fictional scholar Teabing explains how Constantine formed a cynical plan to convert the empire to Christianity, but a hybrid version of the faith that incorporated vast swathes of pagan belief and tradition: “In 325 A.D., he decided to unify Rome under a single religion. Christianity.”

The Council of Nicaea was convened to announce the astonishing and wholly new doctrine of Christ’s divinity. “Until that moment in history,” says Teabing, “Jesus was viewed by His followers as a mortal prophet . . . a great and powerful man, but a man nonetheless. A mortal.” He became Son of God only through a vote taken at Nicaea and carried by a slim majority. This action “was critical to the further unification of the Roman empire and to the new Vatican power base.”

Not a word of this is true. At the most trivial level, the decisions taken at Nicaea were not carried by slim margins: Arius lost by a distinctly non-narrow majority of 298–2 (though the exact count isn’t certain). And in no sense was the emerging theology an upstart concession to imperial ambitions. The idea of Christ’s divinity is firmly present in the New Testament, not least in John’s Gospel when the Apostle Thomas greets the risen Jesus as “my Lord and my God.” This view of Jesus became commonplace during the second and third centuries as Christians participated more in mainstream intellectual life and thus developed their theological discourse and technical vocabulary. And Christians were already very familiar with concepts of the Trinity. By the standards of modern Christianity, Arius’s own doctrines preached a Christ who was unequivocally divine, and few lay Christians today would be able to distinguish his opinions from the orthodoxy of any mainstream church. Arians were a long way from the humanist-inclined teachings of later Unitarianism.

Nicaea did not “make Jesus God,” nor, to take a common modern myth, did it determine the contents of the Christian Bible. In recent times, scholars have rediscovered the large body of alternative scriptures and gospels that circulated in early times, which appeal to moderns because of their psychological insights and the central role that many of them give to female characters. The abundance of competing interpretations also undermines any claims that the familiar canonical Bible might have to special divine authority.

Constantine’s era is regularly cited as the turning point in the toleration or acceptance of such alternative scriptures. Brown’s Teabing claims that no fewer than eighty gospels circulated until Constantine himself more or less overnight created our canon of just four texts: “Constantine commissioned and financed a new Bible, which omitted those gospels that spoke of Christ’s human traits and embellished those gospels that made Him godlike. The earlier gospels were outlawed, gathered up, and burned.”

The thriller writer Brown stands at the extreme end of assertions about this story concerning lost gospels, but he is not too far from other popular writers who have done much to shape contemporary views of the sources of our gospel canon, and Nicaea is generally blamed for these acts of exclusion. But as in the case of Jesus’s supposedly sudden promotion to divinity, the claims are simply wrong. The church was familiar with the standard four Gospels by around 170, and most of the alternative texts portrayed Christ as even more “godlike” than the widely accepted ones. All, moreover, were composed later than the canonical Big Four and were dependent on them.

In reality, the council of 325 never discussed, debated, or decided anything whatever about the shape of the New Testament canon.

Liberals, radicals, and feminists all have their mythologies of Nicaea, but so do the small-o orthodox heirs of the council in both East and West, whether Catholic, Protestant, or Orthodox. According to countless books and classes in church history, Nicaea marked a decisive victory for critical Christian doctrines. The church had declared and defended the doctrine of the Trinity, and from that indispensable foundation it could move on to debate the still more complex issues of the exact relationship between Christ’s humanity and his divinity. Nicaea was the end of the beginning, on this view.

So intuitively obvious is such an interpretation that we might wonder how anyone could ever describe it as a myth, but the term is hard to avoid. In reality, the triumph of Nicene Christianity was a gradual and drawn-out affair, in which victory or defeat was still undecided over half a century later. Meanwhile Arianism, loosely defined, went from strength to strength.

In the new political setup, the fate of Christianity depended on the political and religious outlook of the emperor, his family, and a tiny clique of people who had his ear. In Constantine’s later years, one of his chief counselors was Eusebius of Nicomedia (not to be confused with the pioneering church historian), who may well have baptized the emperor on his deathbed in 337. Eusebius had been a close friend and probably a fellow student of Arius, and only reluctantly had he agreed to the Nicene decisions. In turn, the next emperor, Constantius II, was a disciple of Eusebius, who acquired the crucial position of Archbishop of Constantinople. (At various times, several emperors shared the rule, but Constantius was the dominant figure until his death in 361.)

Constantius labored faithfully to establish Christianity in an Arian or semi-Arian form. He put like-minded believers in important church positions in key cities while purging stubborn defenders of Nicaea. He also encouraged a series of councils that were ever more overt in their determination to overthrow Nicaea. One contemporary complained that “the highways were covered with troops of bishops galloping from every side to the assemblies, which they call synods.”

The Arians enjoyed repeated victories at those gatherings, surprisingly so in light of the common assumption that they were cranky heretics who were unable to understand the plain Trinitarian truth. In fact, the critics of Nicaea were asking excellent questions, focused particularly on the loaded word homoousion/homoousios (“of the same essence”). It had long been associated with the third-century heretic Sabellius, who had denied the Trinity and saw the different divine Persons as parts or modes of one undivided deity. Critics charged that Nicaea had accepted this crude doctrine. Semi-Arians attacked what they saw as Nicene excesses while resisting the temptation to demote Christ to the status of a creature. They tried to avoid or eliminate such contentious terms as the Nicene homoousion and the Arian homoiousion (“of a like essence”), not least because that philosophical language lacked biblical roots.

In 357, the position of “a plague on both your ousia” was accepted by the Third Council of Sirmium (in modern Serbia), which declared that the Father is greater than the Son. Allegedly, even the Roman pope, Liberius, signed the final document. The orthodox Father Jerome reported with horror that “the term ousia was abolished: the Nicene Faith stood condemned by acclamation. The whole world groaned, and was astonished to find itself Arian.”

Political currents were clearly flowing against the Nicene faith. A new assembly at Rimini in 359 drew four hundred bishops, far more than had attended Nicaea itself. This gathering initially endorsed the Nicene Creed, but political maneuverings led the delegates to approve a text that declared the Son to be like the Father, but not necessarily in substance. This is technically termed a Homoian stance, from hómoios, meaning “like” or “similar.”

That formula became the basis of a new creed approved at a council in Constantinople in 360, where debates were firmly guided by Constantius himself. The Son was now proclaimed “similar to the Father who begat him, according to the Scriptures, and whose generation no one knows but the Father only that begat him.”

After a brief pagan interlude under the emperor Julian, his successors resumed their pro-Arian stances. When he came to power in 364, the Western ruler Valentinian tried to balance competing interests, but his brother, the eastern emperor Valens, was aggressively Homoian, a “Liker.”

For forty years after Constantine’s death, the foes of Nicaea enjoyed significant imperial favor. Conversely, the Nicene supporters whom the church remembers as the champions of orthodoxy had to walk a delicate path. At first sight, the pro-Nicene Athanasius seems to have enjoyed an amazingly long tenure in his office of Patriarch of Alexandria, serving from 326 to 373. But that span includes no fewer than five periods of exile, totaling twenty years, when he was shuffled around many distant corners of the empire.

Church historians recall this era as the time of the great Cappadocian Fathers, who did so much to formulate orthodox theology for centuries to come, particularly in the doctrines of the Trinity. The group included Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus. Yet at the time, the Cappadocians were an embattled group that repeatedly had to confront imperial displeasure. If Valens had not respected him so much personally, Basil might have faced martyrdom.

The pro-Nicene cause was saved only by an event that lay far outside the realm of theology. This was the military cataclysm that befell the empire in 378, when Gothic forces defeated a Roman army at Adrianople and killed Valens. He was succeeded in the east by the Spaniard Theodosius, who eventually ruled the entire reunited empire until his death in 395 and became known as “the Great.” In terms of Christian history, he was the most important Roman emperor whom nonspecialists have never heard of.

As I have suggested, Constantine’s career has enjoyed a bright spotlight in popular religious memory. According to that mythology, he made Christianity the empire’s official religion (rather than merely tolerating it), which must have involved suppressing heretical variants of the faith along with their scriptures. Many of those alleged deeds did come to pass, but in the 380s rather than the 320s, and they were chiefly the work of Theodosius rather than Constantine.

For reasons that are still unclear, Theodosius was personally devoted to the Nicene cause. In 381, he summoned the church’s second ecumenical council, which was held at Constantinople and definitively established Nicene doctrines. The new gathering actually expanded the original creed proclaimed at Nicaea to the longer version that has been recited ever since and that is technically known as the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed.

Theodosius demanded acceptance not just of Christianity but of that faith in its precise orthodox and Nicene form, as affirmed in the great churches of Rome and Alexandria. Those who rejected these ideas were adjudged “demented and insane,” to be condemned accordingly: their meeting places were denied the name of churches. Contrary to later triumphalist mythologies, however, Theodosius did not actually forbid paganism, except in a few regions. But the new and harsher religious environment made active pagan worship far more difficult. Led by fanatical monks, Christian mobs destroyed some of the most renowned temples and shrines of pagan antiquity, including the Serapeum in Alexandria. In 385, the Roman empire carried out the first execution of a Christian heretic, the Spaniard Priscillian, although this was notionally for his sorcery and immorality rather than his deviant belief.

This was also the moment at which many of the alternative scriptures genuinely were destroyed or concealed. Again, the new monastics led the charge, taking full advantage of the new imperial commitment to orthodoxy to seek out and destroy vestiges of heresy. Many suspect scriptures were now tucked away, including the famous collection that lay hidden until its rediscovery at Nag Hammadi in 1945. Other texts were presumably fed to the flames.

By 390, the Roman Empire was officially Christian, Catholic, and Nicene, and militantly so on all points.

In an ideal world, this would mark the triumphant conclusion of the long story that began in Nicaea, but in fact we have barely reached the middle of the tale. Not only did Arians survive, initially beyond the Roman frontiers, but they went on to conquer much of the world that Constantine had known.

Through Rome’s long wars with its neighbors, many ordinary people were carried off into slavery, and some of these served as unintended witnesses to Christian faith. Around 310, a boy named Ulfilas was born to a Gothic father and a captive Greek mother in the barbarian lands around the Danube. Ulfilas became a Christian leader among the Goths and undertook a crucial translation of the scriptures into their Germanic language. He was also an Arian Christian, a theology that spread widely among the Goths and neighboring Germanic peoples. In the 350s and 360s, after all, it was the official creed of the still-glorious Roman Empire. Ulfilas also attended the great Council of Constantinople in 360, a fact that acquired a massive new importance at the end of the fourth century when barbarian peoples poured into the Western Empire. Many casually assume that the culprits of these invasions—the Goths, Vandals, and others—were pagans. Most were Arian Christians. The Goths who sacked Rome in 410 were Arian, as were the Vandals who repeated the feat in 455.

By the late fifth century, much of western Europe was dominated by Arian kingdoms, to the horror of a Roman papacy that found itself surrounded by well-armed heretics. Arian Goths ruled Spain, Italy, and southern France; Arian Burgundians controlled the land that would later bear their name. Across much of western Europe, the Latin-speaking heirs of Rome complained that their Nicene or Catholic beliefs were despised and persecuted. When St. Augustine drew his last breath in 430, he did so in the North African city of Hippo, which was then under siege by Arian Vandals. Hippo fell shortly afterwards, followed in 439 by Carthage, which the Vandals made the capital of their powerful kingdom, complete with its own Arian ecclesiastical hierarchy. The Vandals bitterly, albeit sporadically, persecuted Africa’s Nicene Catholics.

If God was seeking to vindicate the truths of Nicaea, he was doing so in a strangely leisurely way. Yet hope lay on the horizon. Around 500, the Frankish king Clovis accepted the faith in its Nicene, Catholic form, and his successors aggressively spread their power over their Arian neighbors. This didn’t happen overnight. Only gradually were the Arian states defeated or converted, and the Lombard peoples of Italy remained Arian well into the seventh century. Europe’s last Arian kings reigned in the 670s.

The Council of Nicaea ended in 325. A mere 350 years later, its principles were firmly established throughout Christian Europe.

Nobody can doubt the significance of the Nicene debates and the council’s conclusions: after all, people were still literally fighting and dying over these issues centuries afterwards. But in no sense was the council itself a decisive ending. The fact that scholars have recorded it in this way indicates the need for historical milestones, especially in matters where truth and error seem to confront each other so clearly. We don’t pay enough attention to the nuances and blips that contradict our neat narratives and their simple chronologies.

In The Sound and the Fury, William Faulkner wisely wrote that “no battle is ever won . . . They are not even fought. The field only reveals to man his own folly and despair, and victory is an illusion of philosophers and fools.” That analysis certainly applies to the Council of Nicaea, which sparked more battles than it settled. Through the centuries, its complex narrative has been concealed by the florid growth of historical and religious mythologies. As we approach its anniversary year, we have an opportunity, and a duty, to treat that well-documented history with the respect that it demands.