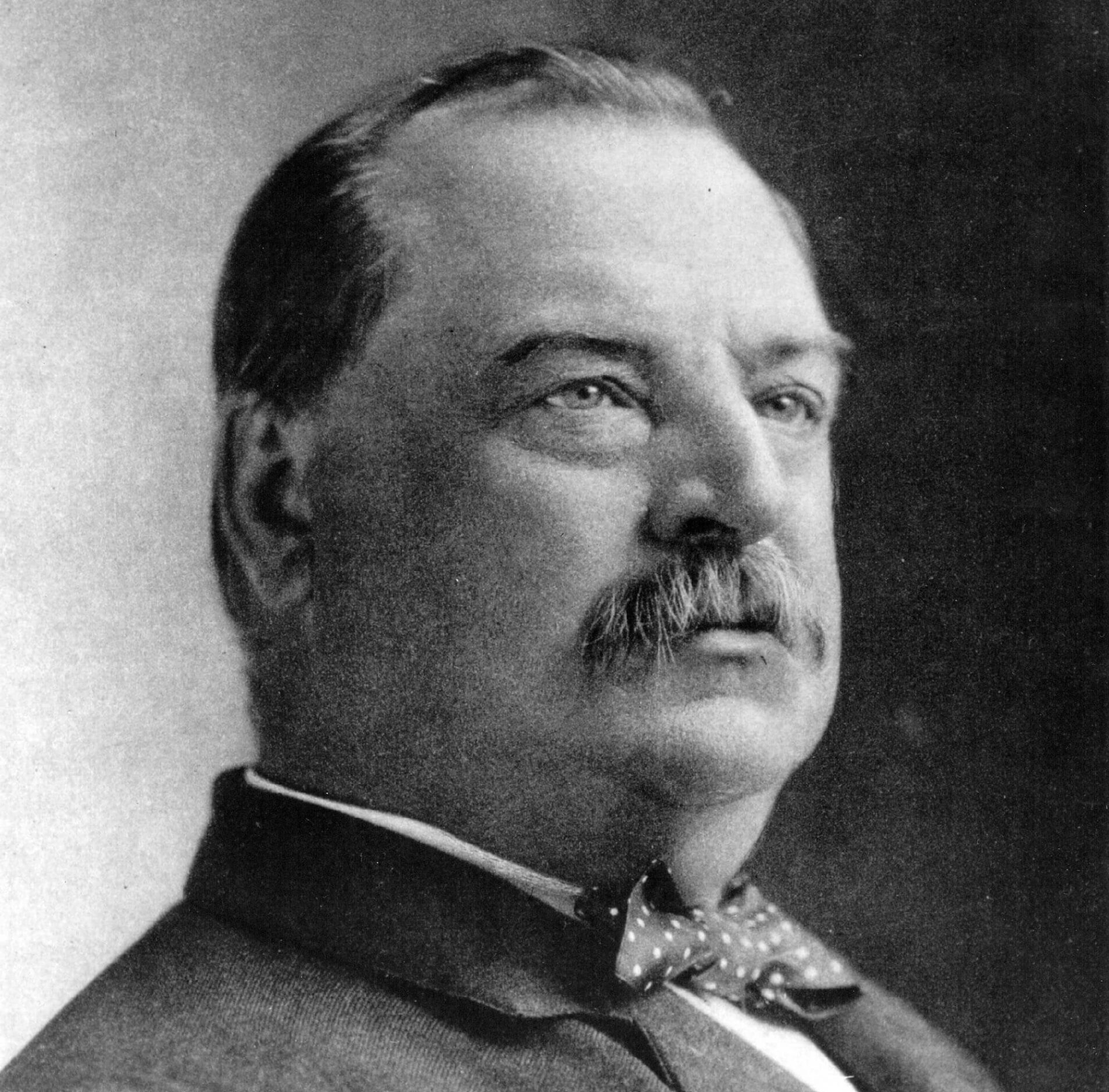

Given how the 2024 campaign has evolved, there is a decent chance that the United States will soon have for the second time in its history a president who serves nonconsecutive terms. Should President Trump win back the White House, Election Night and Inauguration Day will no doubt spawn widespread references to Grover Cleveland as the first to do so, as both our twenty-second and twenty-fourth president.

This historical oddity aside, few know very much about Cleveland—and that is a shame. He was actually one of our better presidents, though that is a relatively low bar to clear considering how ill-served America has been by its chief executives. American greatness has largely come about despite our politicians rather than due to them. Of course, there have been exceptions—Washington chief among them—but Cleveland is not usually considered one of those.

Expert rankings of presidents aren’t very helpful for giving us the straight scoop on presidential performance. The rankings tell us more about those surveyed than about the subjects themselves. The authors of one set of rankings, the Presidential Greatness Project, admitted: “Our latest rankings also show that the experts’ assessments are driven not only by traditional notions of greatness but also by the evolving values of our time.” When it comes to the prevailing values of the professoriate and other public intellectuals, Modern Age readers know that this means a penchant for activist government, collectivism, and wokeness.

How else to explain Lyndon Johnson’s ranking as the eighth or ninth best president, according, respectively, to the most recent Siena College and Presidential Greatness Project surveys? This was a president who oversaw the dual scourges of Vietnam and the Great Society, not to mention domestic unrest and an unraveling of our country’s mores. Just four years before his eighth-place finish in 2022, Johnson was sixteenth in the Siena poll—roughly the same position he had held since 1982, when the survey began. What changed?

One could argue that Johnson was overrated when he ranked in the teens, despite the meaningful shift he led on civil rights and his record of winning on Capitol Hill. As the law professor John McGinnis noted in 2000: “He fought two wars (in Vietnam and against poverty) and lost both of them. The consequences of these policies still harm our polity almost forty years later.”

Woodrow Wilson also exemplifies the point that presidential surveys are mostly mirrors. He was fourth best according to the earliest presidential rankings assembled by the historian Arthur Schlesinger, then sixth best in several other surveys (as late as 2016 in one of them) but has now slipped to a range from thirteenth to fifteenth. Despite his vile racism, Wilson’s ratings hold up among the elite experts who vote in these polls because he was a progressive who grew government (well beyond its proper role), changed the nature of the presidency itself, and was a wartime executive who (disastrously) helped shift the U.S. away from the restrained approach to foreign policy counseled by George Washington. How reflective of true greatness are these ratings?

As for Cleveland, he has generally been considered mediocre by latter-day experts. In 1982, Siena had him at eighteenth. By 2022, it ranked him twenty-sixth. The Presidential Greatness Project also put him at twenty-sixth in 2024, with most other twenty-first-century polls placing him in the twenties. A joint ranking by the Wall Street Journal and the Federalist Society was an outlier, rating him twelfth both in 2000 and 2005. In Recarving Rushmore, Ivan Eland’s iconoclastic examination of U.S. presidents first published in 2009, Cleveland ranked second best based on the author’s more libertarian understanding of the presidency. More surprising, Cleveland—perhaps owing to a partisan advantage and fewer progressive presidents in the pool—was ranked eighth and twelfth in the earliest polls conducted by Schlesinger in 1948 and 1962. Or is it that liberalism changed between then and now? The stated reason for Cleveland being ranked “near great” in 1962 was a recognition of “his stubborn championship of tariff reform and of honesty and efficiency in the civil service.”

Outside of the obvious Jeopardy! question, today Grover Cleveland is almost unknown. Few Americans know who he was; fewer still would argue for his greatness or near greatness. Enter Troy Senik, an admirer of Cleveland who cared enough about this large (and largely forgotten) nineteenth-century president to try to revive interest in him.

Senik has brought Cleveland back into the public eye with A Man of Iron. (And kudos to Simon & Schuster for saying yes to such a book when many publishers would have said, “Are you nuts?”) This concise and well-written one-volume treatment hits the main features of Cleveland’s life and two presidencies. Senik’s book is a welcome addition to the literature on Cleveland and is worth a read by those unfamiliar with Grover the Good.

Readers looking for a less parsimonious examination, however, should consult Allan Nevins’s longer but much earlier biography Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage and his supplemental Letters of Grover Cleveland, 1850–1908. The former, published in 1932, won the author the first of his two Pulitzer Prizes. Nevins clearly favored his subject, but the book is still the classic biography of Cleveland.

Horace Samuel Merrill’s 1957 biography Bourbon Leader: Grover Cleveland and the Democratic Party is a very different kind of treatment. Just as Richard Hofstadter helped define Herbert Spencer (negatively and unfairly, mind you) for the New Deal era, Merrill aimed to interpret Cleveland for his own time. One reviewer at the time, Jeannette Nichols in the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, wasn’t convinced that Merrill’s work made for sound biography, advising readers that they might catch “a case of jaundice” from the book, as it was a “vigorous castigation of Grover Cleveland because he as President from 1885-1889 and 1893-1897 did not actively pursue many of the policies more commonly applauded in 1957.” Caveat lector! Of more recent books, Richard Welch’s Presidencies of Grover Cleveland (1988) will prove most useful for students of Cleveland, but those readers might be disappointed by Henry Graff’s Grover Cleveland (2002), which is marred by the politics of its author.

On the whole, A Man of Iron is among the works I’d recommend to any layperson wanting to better and efficiently understand Cleveland and his presidencies. Senik’s biography begins with a brief introduction that makes the claim that Cleveland was “one of our greatest presidents” even though he did not have “one of America’s greatest presidencies.” Senik finds Cleveland’s greatness to be in his ordinariness; in his character, honesty, and commitment to principles regardless of political incentives; and in his opposition to corruption and strong attachment to the idea that, as Cleveland put it, “a public office is a public trust.” But Cleveland’s presidency is obscure to contemporary readers, according to Senik, because he didn’t hold office during a dramatic time or great crisis (though this is debatable), when presidents were legislative or global leaders, or when they were expected to be visionaries or reshape the office and the nation.

Instead, Senik sees Cleveland as the rare “reactive activist” who believed that his role was to be a “bulwark” for the American people. The man who acquired the nickname “His Obstinacy” believed the president had limited powers. Chief among these was the veto pen, which Cleveland wielded with record frequency. A “Bourbon Democrat” and one of our most classically liberal presidents, Cleveland saw the Constitution as limiting the federal government. Senik admits that this has turned Cleveland, with some justification, into “a minor icon for modern-day libertarians (and sympathetic conservatives).” But this connection with the modern right “elides important distinctions,” especially since Cleveland regulated the railroads with the Interstate Commerce Act and allowed the federal incorporation of unions. Senik also suggests that Cleveland’s presidency cannot be considered great because his second term was “marred by economic depression and labor unrest” that contributed to huge and continuing political losses for the Democrats—and, ultimately, a rejection of his classical liberal political philosophy.

Senik spends the rest of the book familiarizing readers with the man, his upbringing, and his life in politics and in the White House. For those unacquainted with the basic story, Stephen Grover Cleveland was born in New Jersey in 1837 and died there in 1908. But it was in New York state that he first came to prominence, in one of the more meteoric and unlikely ascensions to the presidency in American history. The book is spare when it comes to Cleveland’s early life and upbringing, but Senik nicely captures the extent to which Cleveland “was, by temperament as well as heritage, best understood as a New Englander.” Indeed, I think this explains his emphasis on thrift and honesty throughout his life. Senik’s comparison of Cleveland to the later president Calvin Coolidge is apt, not just in terms of his politics.

Cleveland’s background was not especially privileged: he had a well-educated father who worked as a minister but moved frequently and struggled financially before meeting an early demise. The latter two challenges meant Grover started working relatively young, didn’t make it to Hamilton College as planned, and eventually moved to Buffalo. There his career took off under the tutelage of his uncle, but his rise was hardly predictable, even well into his adulthood. In Buffalo, he apprenticed at a law firm, eventually passed the bar, and practiced law before entering public service as assistant district attorney for Erie County in 1863. This was the same year he dodged the Civil War draft by hiring a substitute to take his place. Cleveland resumed practicing law after losing an election for district attorney in 1865, but he soon ran for office again in 1870 and was elected county sheriff. In this role, Cleveland developed a strong reputation for probity before again returning to legal practice in 1873.

Cleveland’s dramatic political ascent began in 1881, when he unexpectedly won the Buffalo mayoral race and then went after corruption and pork-barrel practices in city politics, to much fanfare. Remarkably, he became president of the United States just a few years later, in 1885. After only a year as mayor, he won the governorship of New York in 1882 and served until the year he became president. Senik’s treatment of Cleveland’s years as governor is short but does highlight how he successfully took on Tammany Hall.

Cleveland’s calling card was, as Senik notes, his “emphasis on economy, integrity, and good-government reforms.” He was an independent man who, consistent with his classical liberal view of government, looked primarily to the public interest rather than to satisfying special interests. Senik observes that the key to Cleveland’s electoral success was his appeal as a “political purgative in a corrupt era.” His straight-shooting “fiduciary” approach allowed him to garner the support of both “loyal Democrats and disaffected Republicans. He was in a party, but never of it.” His forthright politics gained Cleveland the Democratic party nomination in 1884 and, with his victory over the Republican James Blaine in the bruising 1884 election, the party’s first White House win in decades.

Cleveland’s first term as president was less troubled than his second, when he had to deal almost immediately with a severe economic downturn and dangerous labor unrest. Senik notes that a highlight of Cleveland’s first term was how often he vetoed legislation as an “irritable auditor”—he issued 414 vetoes, “more than double the number of vetoes issued by all previous presidents combined.” Thus, much of Cleveland’s first presidency was taken up by his role as a check on Congress, particularly when the latter passed private pension bills like the Dependent Pension Act. Cleveland’s most memorable veto, where his classical liberalism was on utmost display, came in his rejection of the Texas Seed Bill in 1887. He argued: “I can find no warrant for such an appropriation in the Constitution, and I do not believe that the power and duty of the general government ought to be extended to the relief of individual suffering which is in no manner properly related to the public service or benefit.”

Cleveland took on the twin issues that dominated this era of American politics: monetary policy and tariffs. In the former case, Cleveland inherited a problem from the Chester Arthur administration that he waded into even before his inauguration: a potential currency crisis due to the bimetallist Bland Allison Act of 1878. Neither Cleveland and his sound-money allies nor the Silverites pushing the “free silver” line were able to win the legislative battle. But Cleveland put down a marker for the gold standard. Fortunately, a crisis was averted, and the issue died down for the rest of his first term.

Cleveland had another tough battle on his hands regarding tariffs. He favored reducing tariffs and made doing so the keystone issue in his annual message of December 1887, setting the stage for this policy to be the heart of his reelection campaign against the protectionist Republicans. Unfortunately for Cleveland, he lost the tariff battle, and the White House to Benjamin Harrison. Cleveland had won the popular vote and performed even better with voters than he had in 1884, but he came up short in the Electoral College. Senik’s analysis of the loss is that “all the traits that propelled him to higher office . . . tended to shrink rather than expand his political coalition,” thus “hardening” enemies without creating friends. Clearly all good things did not go together in the political realm. But Cleveland nonetheless did a lot of good, including his defense of the public purse from special interests.

Other issues from Cleveland’s first term touched on by Senik include civil service reform, which expanded the number of federal employees protected by law and focused hiring on merit rather than partisan favoritism, rectifying Homestead Act abuse, responding to polygamy in Utah and the Edmunds–Tucker Act that sought to curb it (which Cleveland let become law without his signature), and immigration. Regarding the last, Senik claims that Cleveland’s views were more complex than is often discussed. He argues: “For the most part, Grover Cleveland’s views on immigration stressed acceptance and accommodation.” Indeed, he vetoed a bill that would have excluded illiterate immigrants. Yet he signed the restrictive Scott Act.

There is no doubt that Cleveland held some ugly views on race and ethnicity that were unfortunately all too common. Still, Senik notes that Cleveland was critical of the Rock Springs massacre of Chinese workers and sent federal troops in response (as well as to Seattle to prevent a similar incident). Cleveland also dealt with Native American issues, and, as Senik notes, his “instincts . . . were protective” in the face of ongoing injustices; Cleveland was pro-assimilation and supported the Dawes Act to that end. (It was later amended, which according to Senik contributed to its ultimate failure.)

Cleveland was gone but not forgotten during the Harrison administration and was nominated for a third time by the Democrats in 1892. This time, Cleveland won. As Senik recounts, victory was due in part to his development of a more modern, professional campaign.

Unfortunately for Cleveland, his second term was hamstrung from the beginning by a severe economic crisis—the Panic of 1893—that Senik more than suggests was at least partially due to Harrison’s irresponsible policies. As part of an attempt to end the depression, Cleveland won repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890. Senik, though, suggests that Cleveland’s sound money policy was not exactly the right one during those deflationary times. Cleveland also moved again against tariffs. Alas, the resulting House bill wasn’t a clean tariff reduction act but included an income tax as well. Even worse, the Senate was moving a bill that increased tariffs. When a final bill emerged from Congress, Cleveland let it become law without his signature despite the fact that it did lower rates.

Cleveland also had to face dangerous labor unrest. In his most aggressive show of presidential power, he sent federal troops to Chicago during the Pullman Strike and put the city “under something approaching martial law.” By 1894, Cleveland and the Democrats were in trouble, suffering a crushing defeat in the midterm elections. The economy continued to struggle, and Senik recounts how the administration tried to respond, including with the Morgan bond deal, which held off a collapse of the gold standard. Cleveland’s political life was essentially over early, and his party had changed so much with William Jennings Bryan at the top of the ticket in 1896 that Cleveland ended up (somewhat) privately wanting William McKinley to win. As Senik writes, “By the time Inauguration Day came around on March 4, 1897, Grover Cleveland was exhausted, unpopular, and abandoned by his party.”

Foreign policy was not at the top of the agenda during Cleveland’s first term, but it was a significant part of his second. Senik sums up Cleveland in foreign policy as the “moralist abroad.” But he does note that Cleveland leaned into the traditional American habit of restraint that the U.S. had followed since Washington. In his first inaugural address, Cleveland embraced the “policy of independence” and “neutrality” that the Founders laid out while asserting the importance of “repelling . . . [foreign] intrusions here.”

During his first term, Cleveland dealt with less weighty issues such as putting an end to Chester Arthur’s Nicaragua treaty, boundary problems between Alaska and British Columbia, and fishing disputes (the last two of which Senik doesn’t discuss). Cleveland did have to wade into great power competition with Germany and Britain over Samoa. Senik overly praises Cleveland for forcefully deploying ships there while also seeking a diplomatic solution. Indeed, he argues that it was “perhaps the sharpest foreign policy leadership of either term.”

Cleveland’s most consequential challenges arose in his second term. First was Hawaii, where Cleveland’s “aversion to expansionism” led him to withdraw Harrison’s annexation treaty only days after inauguration and leave the relationship between the U.S. and Hawaii to be settled by Congress and a future president. Second was the Venezuela Boundary Crisis of 1895–1896, during which the United States and Britain almost went to war. In this episode, Cleveland asserted the U.S.’s intention to defend the Americas from foreign designs, putting weight behind the Monroe Doctrine and getting the British to back down. Third was the longstanding Cuba problem, which reared its head right at the end of his term. Cleveland wanted to stay out of the conflict between Spain and its colony, but Congress threatened to push the issue of Cuban independence in defiance of the president. Cleveland did signal to Spain that it should solve problems with Cuba through reform or else the U.S. might eventually get involved. And his administration success fully pushed back against Congress, claiming that recognition of Cuban independence lay “exclusively with the executive.” The U.S. avoided sinking into the conflict during Cleveland’s tenure but wasn’t so fortunate under McKinley.

Naturally for a biography, Senik also discusses Cleveland’s personal life, including his post-presidency and death. He gives an entire chapter to the harrowing tale of Cleveland’s mouth surgery at sea during his second term and a large part of another chapter to his marriage during his first term to his much younger ward, Frances Folsom. Senik closes the book with a discussion of Cleveland’s legacy. He highlights Cleveland’s “moral courage at almost super-human levels.” While Senik doesn’t think Cleveland should be on Mount Rushmore, he doesn’t believe he should be forgotten, either. Presidents who followed Cleveland praised him, and, as earlier noted, the earliest presidential rankings rated him highly. But as Senik explains, Cleveland has been demoted from the higher ranks for a variety of reasons, including that the top issues he faced—such as civil service reform, tariffs, and monetary policy—“seem antique” (or did when Senik wrote the book, before Project 2025 became a 2024 campaign issue) and that “Cleveland’s conception of the role of the federal government—and for that matter, the presidency, now seems so antiquated as to be unrecognizable to the average American.” I’d say the latter hardly seems like a good reason. Indeed, it suggests why Cleveland should be lauded and placed closer to the top of the rankings—and won’t be unless there is a shift in our political culture back toward the classical liberalism that animated Grover the Good.

Senik’s Man of Iron has much to commend. It is a sound telling of Cleveland’s life and presidencies and a book I’d recommend that Americans read to broaden their understanding of our presidents and presidencies. Senik is clearly an admirer of Cleveland. This is more of a virtue than a vice, since a book with an overly critical eye reflecting contemporary political sensibilities has already been produced once and would not allow the more original reflections found here. And it would be unfair to categorize Senik’s book as a hagiography. Indeed, he makes some notable criticisms of Cleveland.

For example, Senik hits Cleveland for his approach to reconciliation and black Americans. He charges that Cleveland—due either to “a lack of imagination or a rare lack of courage”—“never seemed to entertain the idea that black progress was contingent on a more aggressive role for the federal government.” In the elaboration of this critique, Senik suggests a broader criticism of Cleveland’s political philosophy, or at least his constitutional framework: “his conception of the presidency was too brass tacks, too cramped to imagine . . . the ‘bully pulpit’ as a central element of presidential leadership.” Senik also criticizes Cleveland for his response to the Lodge Bill, his idealism around the Dawes Act, and his foreign-policy outlook.

There are a few things Senik might have done differently. Readers could have benefited from more detail about Cleveland’s time as governor of New York. It’s also odd that Senik starts some chapters later in time and then jumps backward, which works better in a film like Pulp Fiction than here. The list of key figures at the front of book might be helpful to those unfamiliar with late nineteenth-century American politics, but it would have been better to fold these brief descriptions into the text when the figures first appear. Lastly, Senik could have spent more time discussing Cleveland’s impact on the judiciary (and his challenges with nominations on the Hill) and on his defense policies, especially since this period was part of the United States’ rise to great power status.

One of the more interesting aspects of Cleveland’s political career is how he connected classical liberalism to a form of populism. Senik understands this, noting that as mayor “Cleveland . . . stumbled upon a winning formula: in an environment as corrupt as Buffalo, being a classical liberal also made him a de facto populist.” Cleveland did the same thing as president, when he concluded, in the biographer’s words, that “lowering tariffs was the true populist position” and using his annual message in 1888 to deliver what Senik calls a “red-hot populist jeremiad” about how losing the traditional skeptical attitude to government empowered private special interests over public interests.

While many classical liberals today rail against the populists in our midst, and many populists rail against classical liberalism, one wonders whether both are mistaken. Could a skilled politician—one like Cleveland, who could win three consecutive popular votes for president—marry classical liberalism and populism to take our country back from corrupted elites, inside and out of government, who work against the national interest for their private benefit? Could someone new see how President Trump has given life to the concerns of those whom others call “deplorables” and fashion an agenda that is oriented towards individual liberty as a means to their rescue?

This agenda would attack the corrupt connections between government and industry, including the military-industrial complex, the same way Cleveland railed in 1888 against the connection of the government to “a favored few” who tax the people for their selfish benefit but “to the injury of a vast majority of our people.” It would argue, as Cleveland did on the campaign trail in New Jersey in 1884, that “every cent taken from the people beyond that required for their protection by the government is no better than robbery.” It would explain how government subsidies and the welfare state enervate society, just as Cleveland often argued, including when he vetoed the Texas Seed Bill: “Federal aid in such cases encourages the expectation of paternal care on the part of the Government and weakens the sturdiness of our national character, while it prevents the indulgence among our people of that kindly sentiment and conduct which strengthens the bonds of a common brotherhood.”

This classical liberal populism would also promote taming the Federal Reserve as a means of protecting the people—especially hardworking and thrifty savers—against the ravages of inflation, as well as cleansing the Augean stables of a foreign-policy establishment that personally benefits from international activism and war to the detriment of the people who pay for them, through their taxes or the ultimate sacrifice. Perhaps collectivism and cronyism should be our targets rather than populism or classical liberalism.

Senik’s verdict on Cleveland’s foreign policy is perhaps where there is most to quibble with. Calling Cleveland a “moralist abroad” doesn’t capture the realism that he often practiced, despite some of his naïveté about the nature of justice in the anarchic realm of international relations. Cleveland was the last president to embrace the Founders’ vision fully, before the fateful turn in American history under McKinley from Washingtonian restraint to an era marked by global activism and empire.

Cleveland understood the dangers of war. He expressed this well in his opposition to the Spanish–American War and the annexation of the Philippines. In his address to a preparatory academy, the Lawrenceville School, in 1898, Cleveland argued that “war is a hateful thing, which we should shun and avoid as antagonistic to the objects of our national existence, as threatening demoralization of our national character and as obstructive to our national destiny.” Yet Cleveland wasn’t unwilling to use force where necessary. He just appreciated the geostrategic advantages that meant the U.S. could pursue restraint in foreign relations—its power and favorable geographic position. Thus he was a liberal realist, in the sense that his anti-imperialism and noninterventionism supported America’s national interests and classical liberal norms alike.

During the Venezuela Boundary Crisis and in Samoa, Cleveland was willing to brandish the stick, even threatening war with Britain in the first instance. He supported expansion and modernization of the Navy while embracing a robust understanding of the Monroe Doctrine. And U.S. forces were used in Panama, Korea, and Brazil to protect U.S. interests. But he avoided global activism, shunning entanglements. Regrettably, Cleveland’s view of arbitration and international law was naïve, and he was a bit precious in his discussion of Hawaii: in its case, a realist could argue that anti-expansionism wasn’t always the best policy. On the other hand, Cleveland’s anti-interventionism served the country better when it came to Cuban affairs, especially given all that would happen as a result of the clash with Spain over Cuba under Cleveland’s successor. As might be expected, Cleveland opposed the imperial policy under McKinley (both the war with Spain and the annexation of the Philippines) and joined the Anti-Imperialist League.

Senik’s “moralist abroad” description seems more fitting for Woodrow Wilson or George W. Bush than Grover Cleveland. Writing in Orbis a few years before Senik published his book, Kori Schake, now the director of foreign and defense policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, argued that Cleveland was a “conservative internationalist” along the lines laid out by Henry Nau in his 2008 Policy Review essay “Conservative Internationalism.” Yet it’s very hard to see in Cleveland someone who meets the key tenets of Nau’s approach (except maybe the third, which is also a hallmark of realism): “1) a clear vision to spread freedom that rises above the ebb and flow of domestic politics and foreign events; 2) an ambitious diplomacy in which the use of force is a continuing companion of negotiations, not a last resort after negotiations fail; and 3) a sense of timely compromise that respects the limits of American power and domestic politics.” Cleveland, on the contrary, extolled the Founders’ restrained vision of nonentanglement and noninterventionism in foreign affairs while opposing expansion ism and warning of the domestic effects of an activist policy.

A last point on Cleveland’s standing today: There is no doubt that his tenure as president was marred by economic challenges. He didn’t win a war or expand government with a signature program. But Cleveland should be honored by more Americans for what he didn’t do, thereby keeping within the constitutional constraints that mark a president in a free society. He wielded the veto in defense of the public interest, he practiced restraint in foreign and domestic policy, and he tried to keep gov ernment limited but strong and clean where it was needed. His personal virtues spilled into his public role. Jacob Heilbrunn, editor of the National Interest, said about Amity Shlaes’s biography of Calvin Coolidge: “Her biography depicts him as a paragon of a president, less for what he did than for what he did not do—Coolidge, she says, ‘is our great refrainer.’” The same could be said about Cleveland—and that is why he was great.