A succession of character types tells the story of what kind of country America is supposed to be. Thomas Jefferson invested his hopes in the ideal of the independent yeoman. His opponents—and some of his friends—favored a character of the sort to be found in the essays of David Hume: a sophisticated citizen well adjusted to a commercial republic.

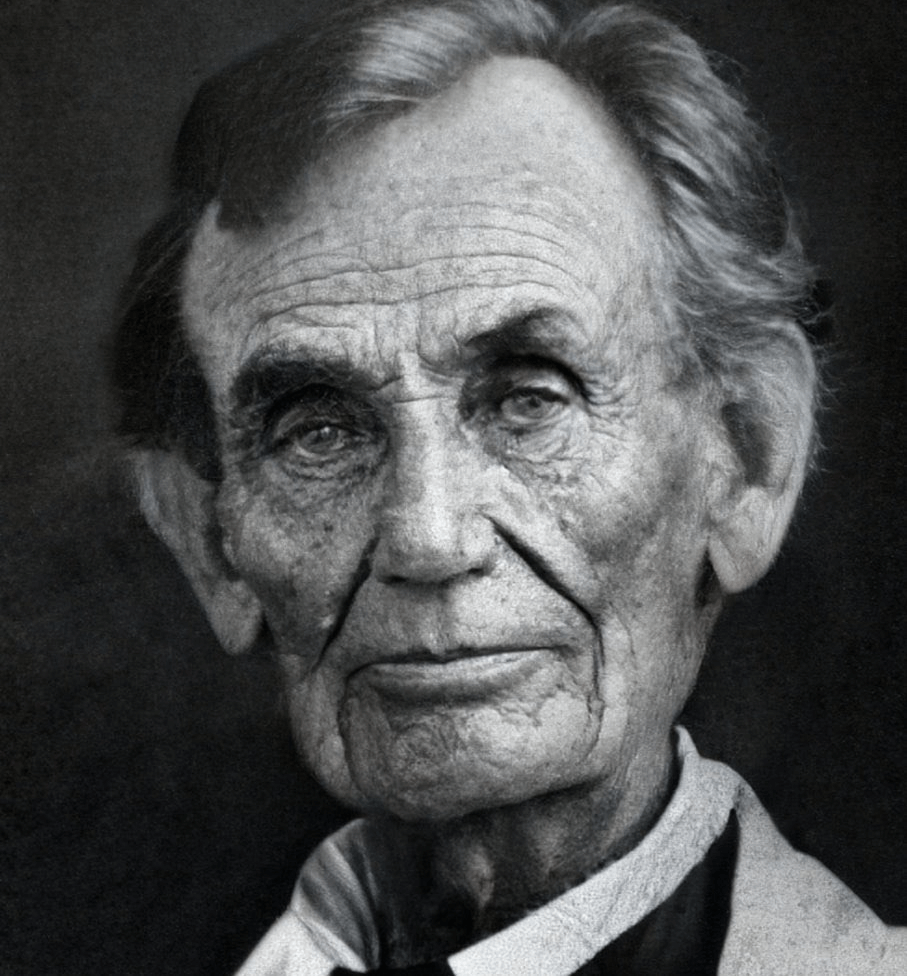

The rabble that made Andrew Jackson president fell short of both models, in the eyes of the gentlemen of the founding generation. But that rabble became the basis for an ideal shared by Jacksonians and Whigs alike: the American as the enterprising workingman, whether farmer or tradesman. His aim was self-improvement, which would inevitably improve the lot of his family and his community as a whole. The Whigs and early Republicans like Abraham Lincoln understood their task as putting government to work for the workingman—the free workingman, that is, who is not a slave and exercises his free agency with respect to employers.

The mid-twentieth-century ideal was something else again, involving an employee who could aspire one day to become an employer, or at least a manager. He could afford a car or two, a house, and a family, and college education for his children. This archetype acquired a feminine counterpart in the career-oriented, college-educated woman who successfully balanced work and family. Private and public sectors alike were supposed to serve these ideals, with Republicans and Democrats differing chiefly on the mix of public and private roles.

What, then, is the archetypal American of today? What kind of society and government does that archetype imply? For progressives, the twenty-first-century American is an autonomous individual with respect to “identity”—everything but race is a choice—yet not autonomous at all where economic existence is concerned. The model American of “The Life of Julia,” an interactive campaign graphic put together for Barack Obama’s reelection effort, is economically dependent on government for the social independence of her lifestyle: federal programs make possible her education and access to health care, her child’s education (she’s apparently a single mother), and even her sex life, thanks to the contraceptive coverage mandated by Obamacare. The life of Julia is a life of minimal agency, responsibility, or human connection.

That life remains the mainstream liberal image of the twenty-first-century citizen, except that Julia today would be a gender-neutral Julium. Jefferson wanted a democracy with the spirit of an aristocracy, every farmer a proud nobleman jealous of his liberty. The humbler, more realistic archetypes of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries envisioned a democracy of self-driven mobility, in which households would have a share to call their own in the commonweal—if not literally a plot of land, then the virtual equivalent of one in human society, an active if not entirely independent place in the community’s order. Now a passive ideal, the citizen as weak and needy—even a victim—has taken hold on one side of the cultural (and not just political) spectrum.

Libertarians propose as an alternative the citizen, or simply the individual, as entrepreneur, whether venture capitalist or Uber driver. It’s a dream derived from the Whigs, but without a strong government underwriting the rules and ground conditions. And the end of the dream is a life that looks a lot like Julia’s, only with the free market rather than government supplying the means to a liberated lifestyle.

Conservatives might ask for something different—a model in which independent citizens and households are nonetheless socially joined up, with government protecting this warp and weft, though not doing the weaving. The economic conditions of the decades to come may be radically unlike those of the nineteenth or twentieth century, however, and much of our society has already been dissolved into atoms. Where does this leave the conservative ideal of American life? Must it be only a rebuke and counterpoint to the other contemporary images?

This issue considers the past and present of these questions, as well as the example of revolutionary social and political change represented by the rise and fall—and aftermath—of the Soviet empire. Conservatives are called today to think radically: first about what would be necessary to bring into being a better American future, if such a thing is still possible; and then about what the conservative’s place and role should be if the country is fated to remain liberal. There are moral, literary, and historical sources to draw upon in pondering this, not least the ones indicated in these pages.

Daniel McCarthy is the editor in chief of Modern Age.

Subscribe to Modern Age »