Tobacco is a plant that once was not to be found in Japan. Written records unfortunately do not agree as to when it was brought in: some say during the Keichō era, and others, the Temmon era. There seems little doubt, however, that by the tenth year of Keichō, tobacco was known in various places, and that in the Bunroku era, it became universally popular.

Moreover, historians seem not at all certain of the identity of the person that introduced it to us. According to some, it was a Portuguese, and according to others, it was a Spaniard. But there is also a legend which tells us that it was without doubt the devil himself that gave us tobacco. We are told in this legend that the devil was brought here by a Jesuit priest: this priest being none other than St. Francis Xavier.

As I say this, I realize that I may displease those of the Christian faith; I cannot but confess, however, that the legend seems to me to be telling the truth. After all, is it not only natural that with the god of the West, the devil of the West should have come too? And that with the good things of the West, must also come the bad things?

I cannot prove, either to my own satisfaction or to yours, that the devil actually did bring tobacco with him. But it may interest you to know that Anatole France, in one of his books, tells us that once the devil tried to tempt a priest with a sprig of mignonette: in the face of such evidence, who can know with certainty that those who say the same devil brought tobacco into Japan are liars? And even if the story is indeed a lie, it perhaps contains greater truth than we may at first suspect.

Such are my thoughts, then, as I begin to tell you the legend of the devil and tobacco.

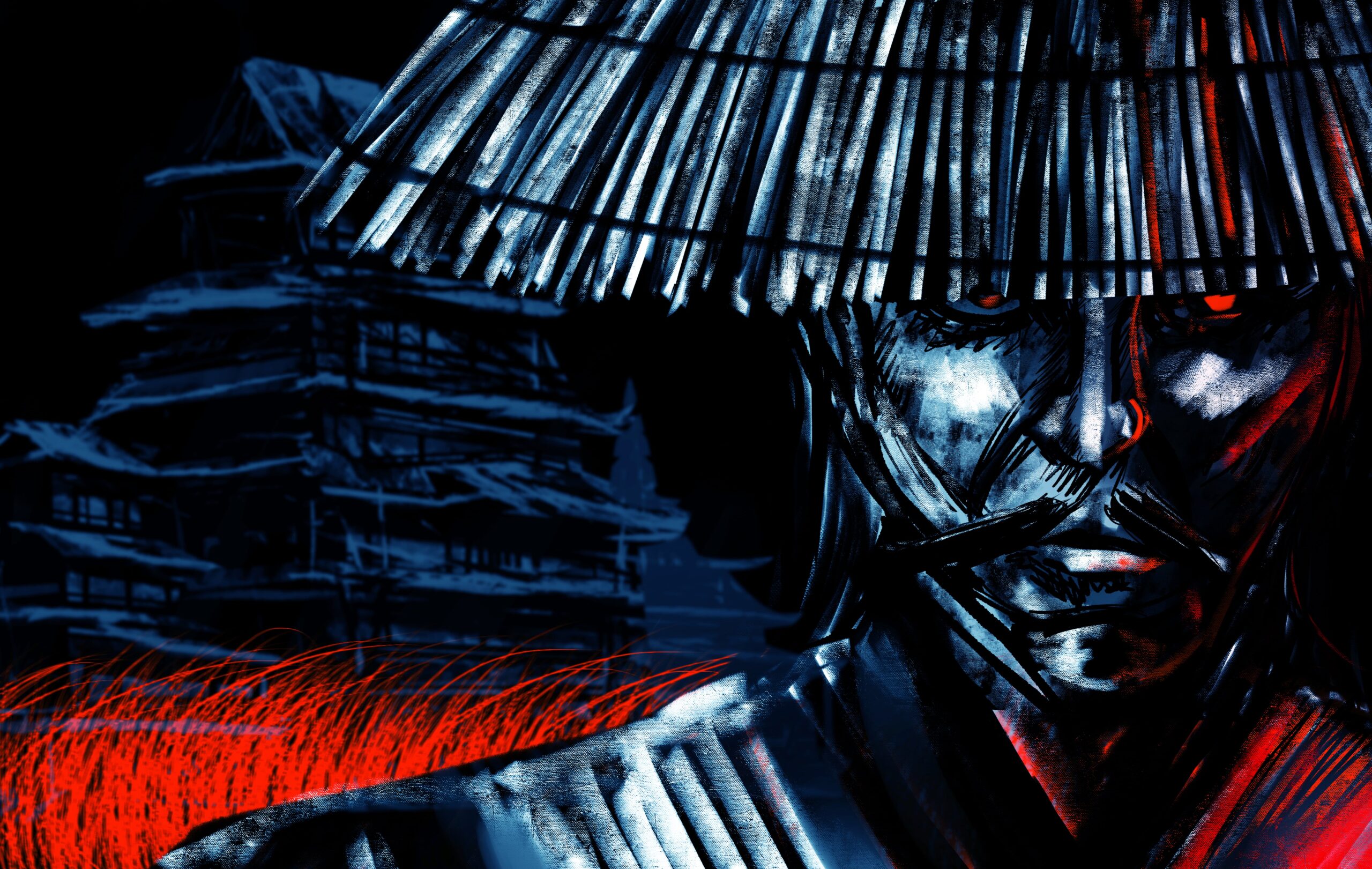

It was in the eighteenth year of Temmon that the devil, disguised as one of the brothers in the company of St. Francis, arrived in Japan after a long journey across the sea. The disguise was made possible by the fact that in some port—perhaps it was Macao—one of the brothers had stayed ashore too long, and the ship, with the rest of the company aboard, had sailed away without him. His absence was not noticed, and the devil, who was hanging upside-down from the yard-arm by his tail, watching all the while for such a chance to appear, quickly changed his form to that of the missing brother, and became St. Francis’ personal attendant. This was quite easy for one so accomplished in the art of disguise as the devil, who could transform himself into a magnificent gentleman wearing a red coat when visiting Dr. Faust.

Surprise awaited him when he first set foot in Japan. Marco Polo’s writings had led him to believe that all the streets of Japan were paved with gold; but even after a careful search, he could not find one such street. He was, however, pleased rather than disappointed; for now he could hope to tempt the Japanese with gold, which he could produce easily enough by rubbing his thumb-nail against a cross. Also, it seemed that Marco Polo had told another lie, when he said that the Japanese knew a way of regaining life after death through some magical use of pearls or some other gem. The devil saw they were as other mortals, and was pleased. It would be easy, he thought, to spread an epidemic by spitting into their wells; and if they suffered badly enough, they surely would soon forget their priests.

Such were his happy thoughts, then, as he walked behind St. Francis through the streets of Japan. There was one difficulty, however, and even the devil could do nothing about it. For it was only a short while since the arrival of the company in Japan, and St. Francis had not yet had the time to spread the teachings of Christ or to make any converts. And without converts, the devil had no one to tempt. He found himself becoming bored, and began to wonder what he could do to pass the time.

After giving the problem of his growing boredom much thought, he finally decided to while away the hours in gardening. Luckily, he had brought with him many different seeds, carefully hidden in his ears. He could easily hire a neighboring field for that purpose; besides, St. Francis wholeheartedly approved of his attendant’s plan. He was under the impression that his subordinate had brought over the seeds with honorable intent, such as growing medicinal herbs.

Having borrowed the necessary implements, the devil began to cultivate with great energy a field by the roadside.

The time was early spring, when the air is heavy with dew, and as the devil worked, he could hear the sleepy boom of a bell carried gently over the floating mist from some distant temple. The sound was quite unlike that of the Western church bells, to which he had become accustomed, and which had seemed to him so unpleasantly piercing. But even in such a restful atmosphere, he could not feel at peace.

Every time the distant bell sounded, the devil would grimace, as though it gave him greater displeasure than the bells of St. Paul’s, and would set himself to work harder than before. For he found that what with the soothing sound of the bell and the warm sunshine, he was lapsing into a state of pleasant lethargy. He did not mind being too lazy to do good, but he saw that if he was not careful, he would lose all desire to do evil, and so fail in his mission, which was to lead the Japanese into temptation. Therefore the devil, who hated manual labor, worked with the hoe in his uncalloused hands, so that he might rid himself of his desire to sleep.

Finally, after many days on the field, he was able to draw the seeds out of his ears, and to plant them.

Some months passed, and the seeds sprouted, and the stems grew; and by the end of the summer, large, deep green leaves covered the entire field. But there was no one who could tell the name of the plant. And even when St. Francis asked him what the plant was that grew in the field, the devil said nothing. He merely smiled, in a knowing and somewhat oily manner.

Then, there began to appear pale blue flowers that were shaped like a funnel; and perhaps because they were the result of his own labor, he appeared to be very pleased with them. Every day, after his day’s work was done, he would go to the field, and tend the flowers.

One day, during St. Francis’ absence—he had gone away for a few days on a mission—a certain cattle-trader happened to pass by the field, leading a cow. And he saw, over the fence, a foreigner dressed in the black clothes of a religious order, standing among his flowers, and busily picking bugs off the leaves. The cattle-trader was much taken with the flowers, the like of which he had never seen before; so he stopped, and taking off his hat, politely addressed himself to the foreigner.

“Pardon me, sir priest, but what is the name of the flower?”

The brother turned. He seemed to the trader to be a pleasant-looking foreigner, with a small nose and small eyes.

“Oh, you mean this.”

“Yes, sir.”

The brother leaned over the fence, and shook his head. Then, in halting Japanese, he said:

“I am sorry, but I cannot tell anyone the name of this flower.”

“I see. Perhaps it was master Francis that forbade you to tell?”

“No, that is not so.”

“Well, in that case, won’t you be good enough to tell me? As you see, I have been receiving instruction from master Francis, and am now of your faith,” So saying, the trader pointed proudly at his chest. A brass crucifix hung from his neck, shining brightly in the sun. Scowling slightly—it may perhaps have been the glare—the brother lowered his eyes for a moment; then he began to speak a little more familiarly, in a tone half serious and half playful.

“I am afraid not. You see, it is against the law of my country to tell anyone. But why don’t you try and make a guess? You Japanese are a very intelligent people, and I’m sure that your guess will be right. And if it is, I’ll give the produce of this entire field to you.”

It is likely that the cattle-trader thought the brother was pulling his leg. With an exaggerated air of concentration, he cocked his head to one side. There was a smile on his sunburnt face.

“I wonder what it is,” he said. ‘‘I don’t think I can give you the answer right away.”

“Oh no. There’s no hurry. I’ll give you three days to think of an answer. I won’t mind if you go and ask someone else. And if you guess right, I’ll give you all this, and some foreign wine besides, or if you wish, a nice religious picture.”

The cattle-trader seemed a little surprised at the brother’s earnestness.

“But what if I guess wrong?”

The brother laughed. And his laugh was so sharp and crow-like, that it gave the cattle-trader a momentary shock.

“If your guess is wrong, you can give me something. Why don’t we make it a bet? Don’t forget, if you are right, you’ll get everything that’s in this field.”

“Well, all right. I’ll give you anything you ask for.”

“Anything? Even that cow?”

“Oh yes. If you want it, I’ll give it to you right now.”

Laughing, the cattle-trader stroked the cow’s head. He seemed to persist in thinking that it was all a joke on the part of the good-natured brother.

“But if I win, you must give me all those plants.”

“All right, it’s a promise then.”

“Certainly, it’s a promise. And I’ll swear by the name of our holy master, Jesus Christ.”

When he heard this, the brother seemed very pleased. His little eyes were shining as he grunted contentedly. Then, resting his left hand on his hip, he began to caress a nearby flower with his other hand.

“If you guess wrong, I shall have your body and soul.” And so saying, he drew himself up, and took off his broad-brimmed hat with a majestic sweep. Growing out of his thick curly hair were two horns, like those of a mountain-goat. The cattle-trader turned pale, and dropped his hat on the ground. At the same time, perhaps because the sun had gone down, the flowers and leaves in the field lost their brightness. Even the cow, as though afraid of something, hung its head, and began to low.

“A promise is a promise, even when it’s made to me. And don’t forget, you swore by the name of someone I myself cannot mention. We shall meet again when three days have passed. Well, fare thee well, my dear sir.”

And so saying, he bowed in mock politness.

The cattle-trader was of course extremely sorry that he had so unwittingly thrown himself into the devil’s hands. Now, it seemed almost certain that the devil would possess him, and that he would burn, body and soul, in eternal hell-fire. It seemed that his recent conversion to Christianity, and his rejection of his old faith, had done him little good.

But having sworn by the sacred name of Jesus Christ, he could not now break his promise. Had St. Francis been there, he no doubt would have helped him out of his predicament, but unfortunately he was away.

He spent two sleepless nights desperately trying to think of a way to find out the name of the cursed plant; but if even the great Francis Xavier did not know, who could possibly know, except . . . ?

The last night of the promised three days finally arrived, and the cattle-trader, leading the same cow, slowly and silently made his way towards the house of the brother, which was on the same side of the road as the field. The brother apparently had gone to bed, for no light showed through the windows. Though the moon was out, it was not a clear night, and over the silent field, the flowers were gently swaying; in the semi-darkness, they looked like ghosts. The cattle-trader had come with a plan, but in the still of the night, he began to be afraid, and wished he were home. And it was not comforting to think of the horned gentleman behind the walls, having pleasant dreams, no doubt, of the inferno. But he could not afford to be a coward. His body and soul were at stake.

And so the cattle-trader, praying to the Virgin Mary for protection, decided to act. He unleashed his cow, and giving it a mighty smack on the rump, drove it towards the field.

Jumping with pain, the cow crashed through the fence, and began to run wildly around the field, More than once, its horns collided with the walls of the house. The sound of beating feet and loud moans broke through the thin mist of the night. Then a window opened, and a face appeared. In the dark, the cattle-trader could not see it distinctly, but he was sure it was the devil’s. Perhaps it was his imagination, but he thought he could see the clear outline of two horns.

“Confound you, you beast, you are ruining my tobacco field!” cried the still sleepy devil, waving his arms about angrily. Indeed, he seemed very annoyed that his sleep had been interrupted.

To the listening cattle-trader, these words of the devil seemed to ring through the night as though they came from God.

“Confound you, you beast, you are ruining my tobacco field!”

Our story, as with all stories of this sort, ends happily. The cattle-trader, much to the devil’s dismay, revealed that he knew the name of the plant, and won the bet. All the tobacco in the field became his.

But, I sometimes wonder, cannot one see a hidden meaning in this ancient legend of ours? True, the devil failed to gain possession of the cattle-trader’s body and soul; but did he not also leave tobacco behind, to be smoked by everyone in Japan? Was there not, perhaps, an element of failure in the cattle-trader’s success, and an element of success in the devil’s failure? The devil falls, and when he rises again, he does so at some cost to us. And sometimes when we resist temptation, we may unwittingly be the losers.

As to the fate of the devil in this country after his encounter with the cattle-trader, I shall say very little. Upon the return of St. Francis, the devil was driven out of the neighborhood. But it appears that he remained in Japan, and wandered about from place to place, still disguised as a brother. According to one account, he was occasionally seen in Kyoto, after the establishment of the Christian church. He lingered for a while even after its abolition under the Toyotomi and Tokugawa governments, but finally he disappeared. There is no more mention of him in the records.

The black ships and the Meiji Revolution brought him back to us, but nothing seems to be known of his movements in recent years—which is a pity.

Akutagawa Ryunosuké was a Japanese author known as the “father of the Japanese short story.”

Edwin McClellan was a British scholar of Japan and translator of Japanese.