“Rooted as they are in facts of contemporary life, the phantasies of even a second-rate writer of modern Science Fiction are incomparably richer, bolder, and stranger than the Utopian or Millennial imaginings of the past,” Aldous Huxley proclaimed.

One only has to imagine possibilities to be in the realm of science fiction. Imagine a species in which there are six genders. Imagine blowing up the sun. Imagine a planet where a duke becomes a messiah, a god, a conqueror of the universe, and then a blind prophet. Imagine fascism arising in America. Imagine totalitarianism being so pervasive that the leader is called Big Brother. Imagine black people solving the racial problem by a mass exodus from this racist planet. Imagine a world in which everyone lives in paradise until being executed at the age of thirty. Imagine a place in which genetics have gone so far as to create supermen and superwomen. Imagine a wagon train to the stars. Imagine . . .

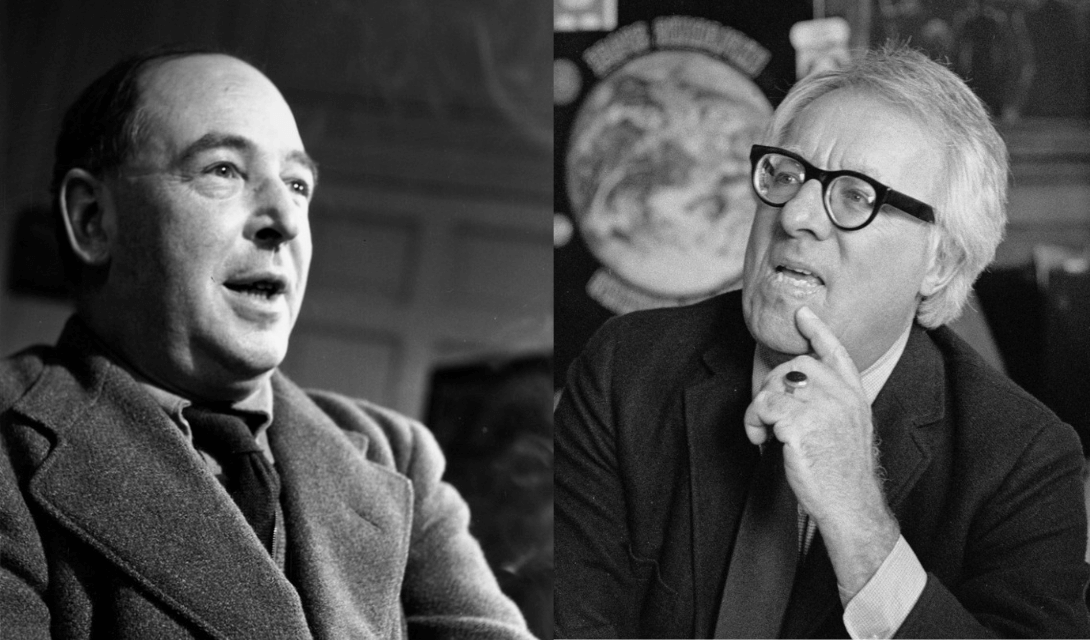

In his seminal essay “On Science Fiction,” C. S. Lewis wrote, “The proper study of man is everything.” He continued, “The proper study of man as artist is everything which gives a foothold to the imagination and the passions.”

Ray Bradbury said something similar several years later. “Over and above everything, the writer in this field [science fiction] has a sense of being confronted by dozens of paths that move among the thousand mirrors of a carnival maze, seeing his society imagined and re-imaged and distorted by the light thrown back at him,” he wrote in Yestermorrow: Obvious Answers to Impossible Futures. “Without moving anything but his typewriter, that immensely dependable Time Machine, the writer can take those paths and examine those billion images.”

He went on, listing “areas into which science fiction shoved its nose again and again”:

Racial relations. Religion. Politics. Are there more? Yes. Philosophy. Pure technology. Art on any level you wish to speak of it. Logic, Ethics, Social science. History. Witchcraft. Time travel. Well, the list, as you can see, is endless. Architecture? But of course! One of the grand thrills of being young and falling in love with science fiction was seeing the early drawings and paintings by men like Frank R. Paul on old magazine covers and inside with each story. They were more often than not pure architectural renderings of fantastic cities, incredible environments. Growing up in science fiction was, then, growing up amidst Everything. Do you see how lucky I was? I grew up in the old field that reached out and embraced every sector of the human imagination, every endeavor, every idea, every technological development, and every dream. Is there a better way to grow up? I can think of none.

As understood by Lewis and Bradbury, science fiction is not only the most ecumenical of all literary genres but also the most libertarian, embracing all possibilities and a vast variety of improbabilities.

C. S. Lewis and Ray Bradbury legitimized science fiction as a genre. In his profound account of the genre, Billion-Year Spree: The True History of Science Fiction, Brian Aldiss claimed, “With the possible exception of Huxley, C. S. Lewis was the most formidable and respected champion of science fiction the modern genre has known.” And Lewis himself had this to say about Bradbury in a 1953 letter to Nathan Comfort Starr:

I have just read two books by an American “scientifiction” author called Ray Bradbury. Most of that genre is abysmally bad, a mere transference of ordinary gangster or pirate fiction to the sidereal stage, and a transference which does harm not good. Bigness in itself is of no imaginative value: the defence of a “galactic” empire is less interesting than the defense of a little walled town like Troy. But Bradbury has real invention and even knows something about prose. I recommend his Silver Locusts [the British name for The Martian Chronicles].

In other correspondence—contained in Jonathan R. Eller’s Ray Bradbury Unbound—Lewis suggested subtle differences between his own work and Bradbury’s fiction: “Is his style almost too delicate, too elusive, too nuancé for S.F. matter? In that respect I take him and me to be at opposite poles; he is a humbled disciple of Corot and Debussy, I am even humbler disciple of Titian and Beethoven.” In Billion-Year Spree, Aldiss wrote of Bradbury,

Those who became successful in the fifties refurbished the worn props. Either, like Bradbury and [Arthur C.] Clarke, by using them with fresh insight; or, like [Robert] Heinlein and Frank Herbert, by expanding the field of vision and using the props together with exotic elements. . . . It was the first writer to recombine the old props in his own way who won the greatest fame. Ray Bradbury’s flamboyant rocket ships took him into a high literary orbit. It couldn’t, as they say, have happened to a nicer guy.

When I contend that Lewis and Bradbury “legitimized” science fiction, I don’t mean to suggest that the genre wasn’t established before the late 1930s. Science fiction has been around for a very long time, even if only in shadow form. Bradbury often dated the whole genre back to Plato’s Republic, an imaginary republic of possibilities, dangers, and glories.

I agree with Bradbury and think it probably did originate with Plato. From that genius forward, we see elements of science fiction in some of the writings of the Stoics, in Cicero’s On the Laws, and in some writings of the early Church Fathers. We also see science fiction in the Renaissance writings of Tommaso Campanella and St. Thomas More, in the poetry and fantasies of the English and German Romantics, in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and in Mark Twain’s Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court.

In the early twentieth century, G. K. Chesterton offered a kind of science fiction with The Man Who Was Thursday and The Napoleon of Notting Hill. Robert Hugh Benson’s gut-wrenching Lord of the World (1907) was arguably the first dystopian novel of the twentieth century. From Benson, one can jump pretty easily to Huxley’s Brave New World and George Orwell’s Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Since the early 1950s, science fiction as a genre has exploded, and it has become nearly impossible not only to keep track of its pervasiveness in novels, film, and video games but even to track its myriad subgenres.

What would become known as science fiction proliferated in America through the pulp magazines of the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. The term “science fiction” itself did not become the generally accepted name of the genre until the 1950s. Before then, a variety of terms had competed with one another: extraordinary voyages, scientific romances, scientific fantasies, impossible stories, pseudo-scientific stories, scientific fiction, scientific stories, weird-scientific stories. These were just a few of the labels given to the genre in the first half of the twentieth century. But in the late 1940s, with the establishment of the Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, “science fiction” seems to have become the leading term.

Though Lewis published in the pulps himself, they were chiefly an American phenomenon. When science fiction such as Lewis’s began to emerge in book form in the 1940s and 1950s, British reviewers did what they could to support it. “Critics such as [Kingsley] Amis and [Robert] Conquest and Philip Toynbee did a great deal to see that it received a favourable reception,” Aldiss explained.

In writing about the pulps, Lewis revealed how ecumenical they could be and how much he appreciated them. “Far the best of the American magazines bears the significant title Fantasy and Science Fiction. In it (as also in many other publications of the same type) you will find not only stories about space-travel but stories about gods, ghosts, ghouls, demons, fairies, monsters, etc.,” he adjudged in “On Science Fiction.”

In his own trilogy of space novels—Out of the Silent Planet (1938), Perelandra (1943), and That Hideous Strength (1945; released in the United States at first as The Tortured Planet)—Lewis takes the reader back to an Aristotelian–Ptolemaic view of the universe, before Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton reshaped our cosmological imagination. Lewis’s Aristotelian–Ptolemaic cosmos is a sea abundant with creatures, the planets rotating in their own separate spheres, moved by angelic powers. In this antique view, there exist the heavens rather than mere space. As Mars and Venus each have their guardian angels, Earth has Satan. Hence, Earth is the Silent Planet, at war with itself and others.

Lewis’s hero, Elwin Ransom, loosely based on J. R. R. Tolkien and Charles Williams, is a Cambridge professor of philology. Kidnapped in Out of the Silent Planet, Ransom travels to Mars and finds himself enmeshed in a war over who controls the planet—the natives and their protectors, the Eldila, or imperialist Earth scientists. In a wickedly clever showdown, Ransom outwits his captors but, in his victory, learns about Earth’s role as the Silent Planet.

Perelandra, the most complex of the trilogy in terms of plot and ideas, sees Ransom travel to Venus to prevent a second fall of Adam and Eve. Serving as the advocate for the Eldila, Ransom convinces the Eve character not to succumb to the temptations of evil. Perelandra is a cosmic struggle of epic proportions.

The best of the trilogy, That Hideous Strength, takes place entirely on Earth, with a bureaucratic entity—the National Institute for Co-ordinated Experiments (NICE)—serving as Satan’s instrument. It is revealed that Ransom is “the pendragon,” the legitimate descendant of King Arthur. He gathers a small company around him, and they do everything in their limited power to thwart the machinations of the NICE.

Set at the end of the twentieth century and in the first third of the twenty-first, Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles (1950) narrates the story of the first several expeditions to colonize Mars. Earth is in chaos and on the verge of nuclear conflict when colonists flee America and immigrate to the fourth planet. Through his masterly interweaving of a variety of short stories, Bradbury considers the most profound existential questions, especially those relating to the human condition and the nature and notion of our humanity.

Lewis’s space trilogy and The Martian Chronicles defined and then redefined science fiction as a genre, making it legitimate for perhaps the first time in its long and variegated history. “It is a fantasy as fantastic as anything ever printed in Weird Tales and the other pulp magazines of supernatural and scientific horror,” Orville Prescott wrote of That Hideous Strength in the New York Times in 1946. “The difference is that Mr. Lewis is a natural story-teller, an acute student of human character, a wise and generously minded man writing with passionate dedication to a noble cause.” Lewis received much praise like this in his own day and after.

The Martian Chronicles met with a similar reception. The New York Times took notice of Bradbury, as it had Lewis, with Harvey Breit interviewing the young author in 1951, asking him rather pointedly if he was “introducing human concerns and values into ray-ridden spaces.” Perhaps most surprisingly, the renowned literary critic Christopher Isherwood praised Bradbury to the skies. In an October 1950 review of The Martian Chronicles published in Tomorrow, Isherwood noted, “Instead of the grunts of cowboys and the fuddled sexual musings of half-plastered private detectives, we are offered adult speculation about the dangers of galactic imperialism and the future of technocratic man.” He continued, “This is not to suggest, however, that Ray Bradbury can be classified simply as a science-fiction writer, even a superlatively good one.” Instead, “he might be called a writer of fantasy, and his stories ‘tales of the grotesque and arabesque’ in the sense in which those words are used by Poe.” Indeed, he proclaimed, “Poe’s name comes up, almost inevitably, in any discussion of Mr. Bradbury’s work; not because Mr. Bradbury is an imitator (though he is certainly a disciple) but because he already deserves to be measured against the greatest master of his particular genre.”

Three things, I think, distinguish Lewis and Bradbury from their fellows.

First, Lewis and Bradbury took God—who He is, what He means, and what can be expected of Him—very seriously. Yet the two men were very different from one another. Lewis was one of the most famous converts to Christianity in the entire twentieth century, while Bradbury, though raised a Baptist, never took to anything that might be called Christian orthodoxy. Bradbury remained deeply skeptical of organized religion throughout his life. Despite this, Bradbury grappled with the notion of God very seriously in his fiction. It almost goes without saying that Lewis did so: from the opening of the space trilogy, God (though rarely named) oversees, providentially, all the events of the three novels. For his part, Bradbury, taking God seriously in his Martian tales, wonders just how the Second Person of the Trinity might appear to fallen human beings in an alien context. (And in his collection The Illustrated Man, Bradbury included a short story—“The Man”—in which Jesus continues to appear on planet after planet, with one man obsessed with chasing Him.)

Both Lewis and Bradbury saw poetic knowledge and language as the highest expression of the imagination.

Second, and critically, both Lewis and Bradbury took seriously the Western tradition, even when in disagreement with it. In Perelandra, Lewis has his hero take a breather before fighting the Unman (the anti-Christ). As he rests and prepares himself to fight, Elwin Ransom remembers “the Iliad, the Odyssey, the Aeneid, the Chanson de Roland, Paradise Lost, the Kalevala, the Hunting of the Snark, and a rhyme about Germanic soundlaws which he had composed as a freshman.” Refreshed, Ransom goes into battle.

With a similar appreciation for civilization’s patrimony, in The Martian Chronicles one of the early explorers, distraught over the devastation of the Martian people by chicken pox, claims that the modern West has done nothing but corrupt all that it touches. The Martians “knew how to live with nature and get along with nature. They didn’t try too hard to be all men and no animal. That’s the mistake we made when Darwin showed up. We embraced him and Huxley and Freud, all smiles. And then we discovered that Darwin and our religions didn’t mix. Or at least we didn’t think they did. We were fools. We tried to budge Darwin and Huxley and Freud. They wouldn’t move very well. So, like idiots, we tried knocking down religion.” (This Huxley, of course, is not Aldous but his grandfather, “Darwin’s bulldog” T. H. Huxley.)

Third, both Lewis and Bradbury saw poetic knowledge and language as the highest expression of the imagination. And each embraced—to the fullest extent possible—the idea of the mythic. Lewis tried to explain his own thought process and the role of imagination in a New York Times article from 1956:

Let me now apply this to my own fairy tales. Some people seem to think that I began by asking myself how I could say something about Christianity to children; then fixed on the fairy tale as an instrument; then collected information about child-psychology and decided what age-group I’d write for; then drew up a list of basic Christian truths and hammered out “allegories” to embody them. This is all pure moonshine. I couldn’t write in that way at all. Everything began with images; a faun carrying an umbrella, a queen on a sledge, a magnificent lion. At first there wasn’t anything Christian about them; that element pushed itself in of its own accord. It was part of the bubbling.

Lewis elaborated on this in a conversation with Aldiss and Kingsley Amis shortly before his own death:

Lewis: The starting point of the second novel, Perelandra, was my mental picture of the floating islands. The whole of the rest of my labours in a sense consisted of building up a world in which floating islands could exist. And then of course the story about an averted fall developed. This is because, as you know, having got your people to this exciting country, something must happen.

Amis: That frequently taxes people very much.

Aldiss: But I am surprised that you put it this way round. I would have thought that you constructed Perelandra for the didactive purpose.

Lewis: Yes, everyone thinks that. They are quite wrong.

A similar story can be told of Bradbury. Shortly after The Martian Chronicles was published, he received Aldous Huxley in his tiny Los Angeles home. As Bradbury recalled in an introduction to the novel,

The Martian Chronicles was published in late spring of 1950 to a few reviews. Only Christopher Isherwood placed a laurel wreath on my head as he introduced me to Aldous Huxley, who, at tea, leaned forward and said “Do you know what you are?”

Don’t tell me what I’m doing, I thought. I don’t want to know.

“You,” said Huxley, “are a poet.”

“I’ll be damned,” I said.

“No, blessed,” said Huxley.

We are all blessed by the imaginative works of C. S. Lewis and Ray Bradbury. We are better human beings because of them. We might even say in the spirit of Edmund Burke, Irving Babbitt, and Russell Kirk that science fiction is the ultimate expression of the moral imagination. It seems only fitting to end with Kirk, who writes in Enemies of the Permanent Things,

Thus the champions of decadence and deliquescence, the enemies of the permanent things, accurately discerned in Ray Bradbury a man of moral imagination, who must be put down promptly. For like Lewis, like Tolkien, like other talented fabulists, Ray Bradbury has drawn the sword against the dreary and corrupting materialism of this century; against society as producer-and-consumer equation, against the hideousness in modern life, against mindless power, against sexual obsession, against sham intellectuality, against the perversion of right reason into the mentality of the television-viewer. His Martians, spectres, and witches are not diverting entertainment only: they become, in their eerie manner, the defenders of truth and beauty.