It reads a little like Tom Wolfe on his worst day ever—like the morning his valet called in sick, he couldn’t locate his thesaurus, and his publisher was expecting the first draft of Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers.

White liberals “surrender their own dignity” to become part of a “masochistic cult which submits to outrageous and, in many cases, patently psychotic charges and attacks” by dashiki-clad “black charlatans.” These “cynical black extremists” exploit “mindless white masochism,” which takes—among other forms—the hosting of “white racism seminars and paying [to have] the most insulting and sickest blacks to come and defecate all over them.”

But that’s not Wolfe. It’s Saul Alinsky in the 1969 edition of Reveille for Radicals, in which the notorious “community organizer” and all-purpose conservative boogeyman also had sharp words for New Left activists. These choice specimens of the white middle class were guilty of “Political Hippyitus,” Alinsky wrote. These “ignorant and confused,” if well-educated, boys and girls wanted peace, equality, and freedom so they could “do their thing” before—at about the age of thirty-three—chucking it all and retreating into the comfort of the suburbs from which they sprang.

Alinsky was clearly ornerier and more unsettling in his opinions than those on the left who profess to admire him seem to realize, and they would do well to study him again. By the same token, he had much to say that would benefit their counterparts on the political right who faint at the very mention of his name.

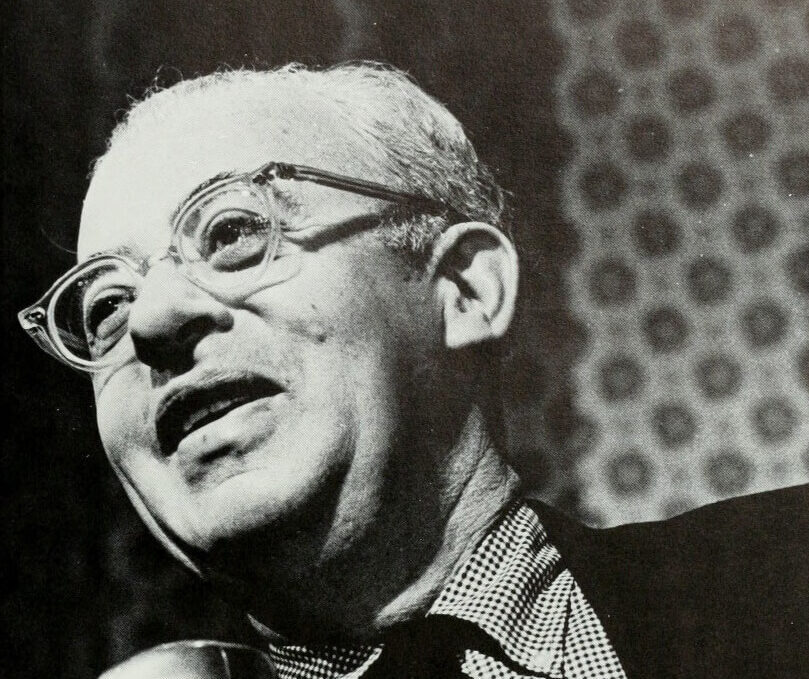

Founder of the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF), self-described “radical” and pioneering practitioner of “community organizing,” Alinsky (1909–1972) was born to Jewish immigrants from Russia in “one of the worst slums” of Chicago, studied sociology at the University of Chicago, and in the early 1930s began his career in what John Jay Chapman, in another context, called “practical agitation.”

Unusual among such organizations, the IAF lives on, though by Alinsky’s own reckoning the success of these kinds of outfits was never to be measured by their longevity. Whenever any such group achieved more or less permanent status, it almost always meant it had been taken over by well-paid bureaucrats, dependent on tax dollars and effectively neutered.

Alinsky’s approach, as the New York Times reported in the mid-Sixties, was “an explosive mixture of rigid discipline, brilliant showmanship, and a street fighter’s instinct for ruthlessly exploiting his enemy’s weakness.” He could be mean, uncouth, and outrageous, but was hardly doctrinaire. “For Saul,” according to the late journalist and author Nicholas von Hoffman, who worked for Alinsky in the 1950s, “organizing varied in method, shape, and scope depending on the times and the circumstances.” He was a “radical” but never an ideologue. This makes Alinsky and his work hard to pigeonhole, though God knows people have tried.

Conservatives have reviled Alinsky for decades, knowing little about him and his work but associating his gleefully disruptive, often pro-union and anti-management activities with all that they found objectionable about the Sixties. This includes Alinsky’s involvement with Cesar Chavez, whom he advised, and the United Farm Workers’ table grape boycott of 1968. (Loving nothing quite like a good grudge, some people are still steamed at how, in 1876, Hayes beat Tilden.)

Right-wingers also associate Alinsky with other people they don’t like, notably Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama. Clinton, then Hillary Rodham, wrote a college paper about Alinsky, leading the American Spectator journalist David Brock—before his conversion from right to left—to dub her “Alinsky’s daughter.” When Obama defeated Clinton for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2008, critics on the right redirected their wrath at Obama, who actually worked as a “community organizer” in Chicago from 1985 to 1988, by which time Alinsky had been dead for more than ten years. David Horowitz, in Barack Obama’s Rules for Revolution: The Alinsky Model, traced the Obama administration’s “effort to subject America to a wholesale transformation” to that “guru of Sixties radicals.” About that time, Glenn Beck did his part, too, alerting his country men to Alinsky’s “vision for a Godless, centrally controlled utopia.”

What’s remarkable, considering this garish backdrop, is the extent to which a number of right-of-center activists have been learning from Alinsky, if not ever admiring him or his colorful career. There’s evidence that Tea Party activists took to heart some of his tactical preachments, and they have certainly encouraged others to do so. Michael Patrick Leahy, one of their early honchos, has circulated “sixteen rules for conservative radicals based on lessons from Saul Alinsky, the Tea Party Movement, and the Apostle Paul.” Steve Deace of Blaze Media has published Rules for Patriots: How Conservatives Can Win Again, based in part on Alinsky’s “infamous” Rules for Radicals, sporting a similar cover design, “with foreword by David Limbaugh.”

None of this is as mysterious as it might first appear, given the areas in which Alinsky’s analysis and that of theorists on the right in fact converge. Both oppose what has been called the Deep State and the overweening power of big institutions associated with it, dependent upon it, and contributing to its growth. Alinsky “feared the gigantism of government, corporation and even labor union,” von Hoffman wrote in Radical: A Portrait of Saul Alinsky:

The hope of his life was democratic organizations which could pose countervailing power against modern bureaucracies. It was only in that way, he thought, that personal freedom and privacy could be maintained. He did not trust the courts and legal protections to preserve individual liberty. It had to be backed up by countervailing power. For him, as he would often say, it was the struggle of the little man against big structures.

Alinsky, that is, put his trust in the importance of what Peter Berger, Richard John Neuhaus, Michael Novak, and others in the late 1970s and early 1980s called “mediating structures,” those voluntary, independent, often local institutions that stand between the individual and the state, which has since then grown only more meddlesome, obnoxious, overbearing, and incompetent (and also more costly and wasteful).

In language reminiscent of Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, Alinsky expressed his disgust, too, with the “gigantic welfare industry” that by the late Sixties was gaining a foot hold in major cities. This generously funded “welfare establishment” had “mushroomed to the extent that it must now be classified as one of urban America’s major industries,” enriching its administrators while solidifying their near stranglehold on addressing the problem of poverty, and with precious few successes.

Such talk would appall today’s liberals, if they read Alinsky, which it seems apparent they do not. If they did, they would be brought up short repeatedly and have less reason to wonder why such great chunks of the electorate have come to despise the Democratic Party leadership and support Donald Trump.

These are, of course, Americans referred to in 2016 as “deplorables.” They are men and women whose attitudes on so-called social issues tend to be time-honored and traditional; they are uncomfortable with change, especially when foisted on them by those who consider themselves more enlightened. They did not for the most part matriculate at Ivy League universities, and, as Obama put it, they “cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren’t like them or anti-immigrant sentiment or anti-trade sentiment as a way to explain their frustrations.”

Even in his day, Alinsky saw how these people were looked down on by their better educated countrymen affecting “liberal, democratic, holier-than-thou” attitudes, as he wrote in his 1971 book Rules for Radicals, and that they resented it. They were “hurt, bitter, suspicious, feeling rejected and at bay” as they witnessed “values they held sacred sneered at.” At the same time, taxes “on incomes, food, real estate, and automobiles, at all levels—city, state, and national” ate away at their earnings. And this was before the neoliberal agenda of the Clinton years led to globalism, the export of jobs, and the closing of mines and factories.

Feeling “threatened from all sides,” Alinsky wrote, they often embraced an “extreme chauvinism” as their “fears and frustrations” built “to a point of a political paranoia.” The worries and grievances of these “fearful people,” as Alinsky called them, were real and should be treated with the same respect as those of more ideologically favored constituencies. “They cannot be dismissed by labeling them blue collar or hard hat,” as was the case not so long ago, and if “we fail to communicate with them, if we don’t encourage them to form alliances with us, they will move to the right.” Alinsky wanted his followers to work with them, “as one would work with any other part of our population—with respect, understanding, and sympathy.”

References to “blue collar” workers and “hard hats” sound quaint today, in part because so many plants and mines have closed, and old ways of earning a living and supporting a family have disappeared. Alinsky used the language of his day, and it sometimes does evoke an America that no longer exists. It is language from the time of Tom Joad and FDR, with references to “the common man,” the “workingman” who shows up every morning at “the factory gate.” The bosses Alinsky refers to are always men, and wives seem to stay home to look after the kids. Home for the most part was a neighborhood near the factory inhabited for generations by families of the same ethnic and religious background.

But Alinsky was also, by 1971, coming to see how America was changing. In the “highly mobile, urbanized society” that was emerging, our understanding of “community” itself had to change. Even then, community had begun to mean “community of interests, not physical community,” and would require different methods to connect, unite, and motivate members.

What would not change was the need for “originality” in our activism, and he had no shortage of ingenious ideas. He also understood, as almost no one in politics does today, the importance of an enlivening spirit of whimsy and mischief. His response to Chicago Mayor Richard Daley’s failure to move promptly on inner-city health and safety problems was to threaten to let loose a thousand rats at City Hall. Alinsky called this a “sort of share-the-rats program” and a “form of integration.” Then, in Rochester, determined to stimulate the city’s cultural and political elite to action, he let it be known that he would host a baked-bean only dinner to precede a performance by the Rochester Philharmonic. A “flatulent blitzkrieg,” as he called it, would follow: once Alinsky’s dinner guests took their seats in the concert hall, as von Hoffman recalled, “they would sit expelling gastrointestinal vapors with such noisy velocity as to compete with the woodwinds.”

Neither the rat release nor the “fart-in” ever took place, but that is almost beside the point. “The threat is usually more terrifying than the thing itself,” Alinsky explained, and you know what is even more terrifying still? Ridicule. “Ridicule is man’s most potent weapon. . . . It is almost impossible to counterattack ridicule.” Effective ridicule—unlike schoolyard name-calling—requires a sense of the absurd, and that is almost wholly lacking in American political life today. We have worked ourselves into such a lather of righteous indignation that we have lost our ability see how comical it all is, and it’s just no fun anymore. “A good tactic,” Alinsky said, “is one that your people enjoy,” and who these days finds any of it enjoyable?

Any political movement that takes itself too seriously will sooner or later pay the price, at the very least by losing the talent of imaginative members. Whenever he was asked why he never became a card-carrying communist, Alinsky had a ready response. “I didn’t join,” he said, “because I had a sense of humor.”