“What is a conservative, after all, but one who conserves,” said President Ronald Reagan in 1984. “[W]e want to protect and conserve the land on which we live—our countryside, our rivers and mountains, our plains and meadows and forests,” he declared, “This is our patrimony.”

This is not language heard often from conservatives today.

Last year Republican Sen. Mike Lee wrote on X, “If you’re in office and you have a climate-change agenda, you’re part of the problem.” Many conservatives know exactly what the senator meant—giving into the political pressure and fear-mongering of leftist “green” advocates who are more interested in attacking free markets and enhancing government power than they are in actual conservation.

The Democrats’ “Green New Deal” of recent years was nothing more than a “socialist super-package” that would have crippled the economy and was stuffed with all sorts of items that had nothing to do with the environment. Most of what purports to be the environmental movement now really is a front for socialism and an overall radical progressive agenda.

But green scam-artists aside, should caring about the environment be exclusively a left concern? If the very word “conservative” signifies trying to conserve something, is nature off that list?

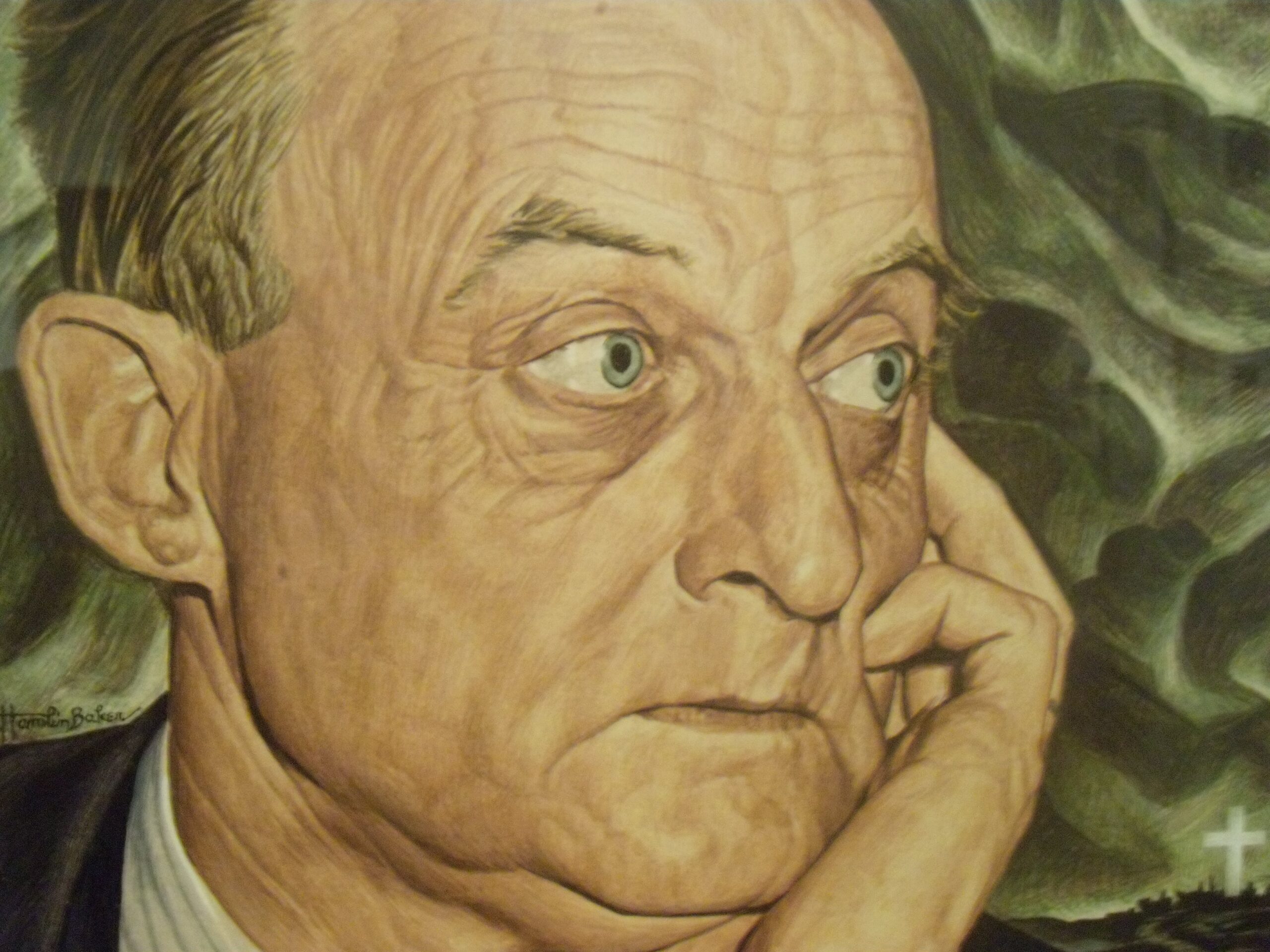

Modern Age’s founder Russell Kirk insisted, “There is nothing more conservative than conservation.”

That’s also the argument made in the recent book The Conservative Environmentalist: Common Sense Solutions for a Sustainable Future, in whose pages author Benji Backer methodically offers right-leaning, pro-market solutions to what he identifies as genuine environmental concerns, while also attacking dubious claims that the left masks as green initiatives.

Backer, the twenty-seven year old founder of the American Conservation Coalition—which he calls “the largest right-of-center environmental organization in the country”—injects urgently needed non-socialist ideas into environmental thought and debate. Backer wants to fix environmental problems but points out how some environmental advocates’ policies have produced harmful results.

Backer uses some of the highest-profile Republicans of the past half-century to make his case for raising environmental issues on the right. President Theodore Roosevelt gets an obvious mention. An endorsement from action movie star and former Republican governor of California Arnold Schwarzenegger, who signed the Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006, adorns the book’s jacket. Backer notes President Richard Nixon’s creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, as well as his legislative legacy which includes the National Environmental Policy Act, Clean Air Act, and Endangered Species Act. He also cites President Reagan’s efforts to “mitigate the national ozone crisis by establishing the international Montreal Protocol . . .”

Backer reminds us that President George H. W. Bush vowed to become the “Environmental President” and signed the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments (CAAA), “the most expansive environmental regulatory legislation in the nation’s history.” His son, President George W. Bush, signed the Healthy Forests Initiative, which “helped restore valuable woodlands and rangelands and reduce forest fires.”

Citing the conservation efforts of Republican presidents is smart. But there is a deeper conversation to be had about conservation and conservatism, and it should begin with that preeminent conservative environmentalist Russell Kirk.

The late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia said of Kirk, “No one had a greater role in the formation of American conservative thought,” and much of his movement-shaping mind centered on land, nature, man’s place in it, and our responsibilities toward it.

And he didn’t hold back. In 1968, Kirk wrote, “Man, Enemy of Nature,” a title that might sting right-wing ears in 2025, for his syndicated newspaper column. With a focus on his home state of Michigan, Kirk argued, “man’s assault on nature is . . . deadly and persistent. Lake Michigan is being poisoned by man’s industrial and domestic wastes, so that within this century it may ‘die,’ its fish destroyed by a human upsetting of the natural balance. It may become a vast sewer in which no one can swim: that has already happened to Lake Erie. It is happening speedily, in the neighborhood of Muskegon, to smaller inland lakes connecting with Lake Michigan.”

“In our 20th century, humankind is proud of ‘conquering nature,’ by tools that vary from the bulldozer to insecticides,” Kirk added. “But like other merciless conquests, this victory may end in the destruction of the victor.”

A human being worried about his kind ruining the environment they inhabit? Was this leftism? No—this was a genuinely conservative and practical concern before it became filtered through today’s distorted partisanship.

Kirk planted hundreds of trees at his home in Mecosta, Michigan, and throughout the county. This wasn’t simply because he had a green thumb and liked the outdoors. For Kirk, it was conservatism in practice. He wrote in 1962, “This spring my man George and I planted more than two thousand saplings upon my infertile ancestral acres. To plant a tree nowadays—particularly an oak or an elm, on badly watered land—is an act of hope and faith.”

Kirk continued: “Edmund Burke, writing at the inception of the revolutions of our age, feared that an epoch was at hand in which men would become as the flies of a summer, generation unable to link with generation. In most of the world, this has come to pass. We moderns live for the evanescent moment, and for our moment in particular.”

“But when a man in his 40s plants a tree, it is not for himself,” Kirk asserted. “By the time that tree is grown, the planter will be lapped in lead or, in our unpoetic time, hermetically sealed in a stainless steel casket in Idle Hours Cemetery. So only a man who remembers his debt to his ancestors is likely to plant for posterity.”

For Kirk, the trees he planted were part of Burke’s eternal bond between “the dead, the living, and the yet unborn.”

Ronald Reagan conferred the Presidential Citizens Medal on Kirk in 1989. In that moment, a decade shy of the new millennium, two of the most prominent conservatives of the twentieth century would have found it bizarre that their credo would ever be adverse to conservation.

To be fair, many conservatives in our time have no problem with “conservation” as a term or concept, either, and would quickly note that environmentalists today are often just promoting far left ideas which have nothing to do with conservation.

But there is a language barrier between conservatives and earnest conservationists of other political stripes. In his book, Backer notes that Republican governors with strong environmental track records, such as Georgia’s Brian Kemp and Florida’s Ron DeSantis, never use the phrase “climate action.” They talk about clean energy, clean air, upgraded infrastructure, and the like.

Language is important in persuasion. Kirk and Reagan would have been comfortable with the watchword “stewardship.”

Kirk not only believed there was nothing more conservative than conservation, he also believed conservatism was the opposite of ideology—and environmental concerns should not be ideological. They were too important. Kirk wrote in 1971, “The issue of environmental quality is one which transcends traditional political boundaries. It is a cause which can attract, and very sincerely, liberals, conservatives, radicals, reactionaries, freaks, and middle-class straights.”

The American conservative movement has evolved over time and will continue to do so. But philosophies and movements mean nothing if they don’t have definitive parameters, bedrock principles that never waiver. It is the conservative who should conserve. It is the radical who disrupts. “Every right is married to a duty, every freedom owes a corresponding responsibility,” Kirk wrote.

We can continue to debate how conservative principles should be articulated. But Russell Kirk was right: environmentalism should always be one of them.