“I thought wonder had gone out of stories after The Sea Children and other strange tales that enchanted my childhood. Now here it is all back again. I wonder by what magic you managed to free your imagination in these crabbed times.”

—Robert Hillyer to Ray Bradbury, September 1959

The science fiction and fantasy author Ray Bradbury holds an unusual place in American letters. Ignored or undervalued by a sizable portion of the critical elite during his lifetime, he nevertheless became one of the most popular and anthologized authors of the twentieth century on the strength of such thought-provoking short stories as “A Sound of Thunder,” “There Will Come Soft Rains,” and “The Veldt” and the novels The Martian Chronicles, Dandelion Wine, Something Wicked This Way Comes, and especially Fahrenheit 451, a midcentury divination of a forced-egalitarian, tech-addicted future that reads today like creative nonfiction.

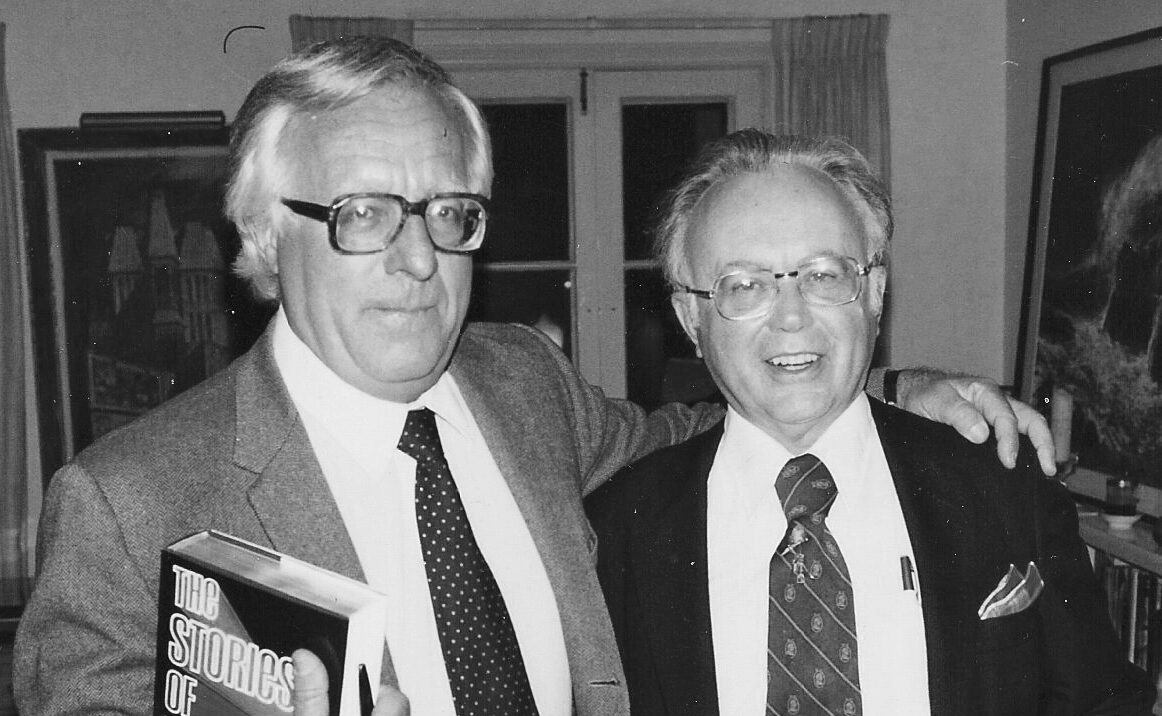

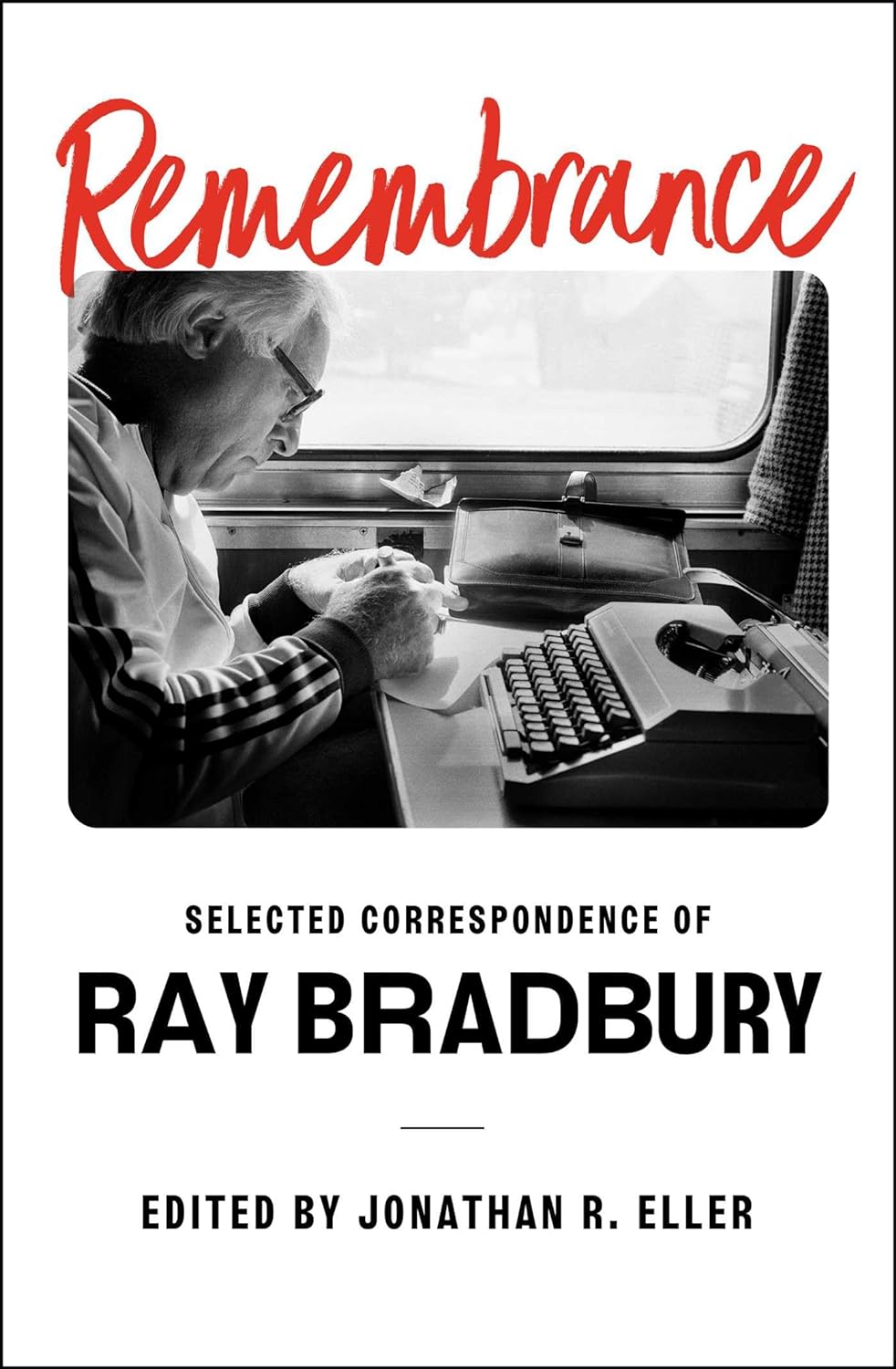

Several factors may account for the elite’s ambivalence, among them Bradbury’s meteoric early ascent through the critically unfashionable worlds of pulp magazines and scripted radio, the shaky reputation of the genre with which he was so closely identified, and his unapologetic sentimentalism. Nevertheless, a good number of writers adored this Illinois-bred, Hollywood-infected dreamer, a fact made abundantly clear in the recently published Remembrance: Selected Correspondence of Ray Bradbury. Atypical of the collected-letters genre, this volume, meticulously edited by the Bradbury scholar and biographer Jonathan R. Eller, includes both outgoing and incoming messages. The inbound missives from the likes of Robert Hillyer, Gore Vidal, Faith Baldwin, Anaïs Nin, Jessamyn West, and Helen Bevington at times resemble fan mail. Elsewhere, Thomas Steinbeck recounts his father John’s infatuation with Bradbury’s work, and collegial letters from W. Somerset Maugham, Graham Greene, and Carl Sandburg underscore these literary heavyweights’ acceptance of the one-time “poet of the pulps” as an equal.

Letters to and from fellow science fiction writers are also well represented, but the preponderance of correspondence with artists outside of the genre speaks both to the universality of Bradbury’s work and to its uncertain position within the often rigidly defined world of sci-fi—a tension previously noted by Sam Weller in his biography The Bradbury Chronicles:

The sci-fi purists, in their myopic love affair with hardware, did not understand that Ray Bradbury cared little about technological accuracy. His stories were, at their nucleus, human stories dressed in the baroque accoutrements of his early science-fiction influences.

Bradbury was not the first “literary” science fiction writer. Indeed, Bradbury’s mentor Henry Kuttner matched his protégé for depth, linguistic facility, and inventiveness. But there was an X factor that set Bradbury’s work apart—a quality that enabled him to break into the rarefied pages of Collier’s, Harper’s, the Saturday Evening Post, Playboy, and the New Yorker. Russell Kirk, who was arguably Bradbury’s most vociferous literary booster, identified this as a longing for, and defense of, the permanent things. So many of Bradbury’s lyrical tales of far-flung space expeditions, fantastical carnivals, time-traveling safaris, and the more prosaic environs of small-town Illinois circa 1928 are suffused with a palpable wistfulness. There is the sense that, in throwing ourselves headlong toward the future, we continually risk abandoning what was most precious in our past. In Fahrenheit 451, the Great Books themselves are at risk, along with the accumulated cultural history of Western civilization. In the haunting short story “Mars is Heaven!,” an elite crew of space colonizers lands on Mars to discover that what they have truly been seeking, in their innermost hearts, is the vanished landscape of small-town America (a longing that the clever Martians use against them). And throughout the entirety of Dandelion Wine, Bradbury pays tribute to the Midwestern childhood that kept him grounded and inspired throughout his life.

Championing the time-tested values of the past is not an aim one normally associates with science fiction authors. Perhaps it should come as no surprise that Bradbury, formerly a committed liberal and Democrat, moved toward an inchoate conservatism as he aged (although he ultimately eschewed the labels “liberal” and “conservative”). After all, the impulse to reclaim what has been lost, or reaffirm what may be in danger of being lost, is surely a conservative one.

“Bradbury’s stories are not an escape from reality,” Kirk wrote in his 1969 survey of culture and politics, Enemies of the Permanent Things. “They are windows looking upon enduring reality.” Remembrance contains several samples from these two writers’ longstanding correspondence (born of a warm and abiding friendship) that expand on this theme. Responding to Kirk’s conscription of him as one of the “chief architects of true normality, along with T.S. Eliot and Max Picard,” Bradbury responds that this idea fills him “with secret amusement and delight,” and then goes on to give a uniquely Bradburian distillation of philosophical conservatism:

Of course, each of us knows that we are not normal, each of us is some kind of monster kept each in his own tower, a private keep somewhere in the upper part of the head where, from time to time, of midnights, the beast can be heard raving. To control that, to the end of life, to stay contemplative, sane, good humored, is our entire work, in the midst of cities that tempt us to inhumanity, and passions that threaten to drive through the skin with invisible spikes.

Writing these words in 1967, Bradbury was one year away from his split with the Democratic Party to back Richard Nixon for the presidency—less an assertion of a new political orientation than a protest against Lyndon Johnson’s profligate and open-ended prosecution of the war in Vietnam.

Truthfully, Bradbury’s political thinking was underdeveloped. He trended Republican from the late 1960s onward, but his thoughts on the relative merits of George W. Bush, Reagan, Nixon, Johnson, et al., (which can be found in Weller’s Listen to the Echoes: The Ray Bradbury Interviews) are typically less interesting than his insights on the psychological undercurrents that drive us to our political choices in the first place. Eller largely avoids showcasing Bradbury’s amateur political punditry in Remembrance (probably a wise move, though it would have been fascinating to read any extant exchanges with Kirk during the Reagan era, when, according to Eller’s biography Bradbury Beyond Apollo, the two men were in sync politically), opting to highlight two letters from 1952 that, taken together, arguably encompass the full range of Bradbury’s thinking on these matters. The first, his well-known “Letter to the Republican Party,” which ran in Daily Variety (and later in the Nation), calls out a then-contemporary target:

In the name of all that is right and good and fair, let us send McCarthy and his friends back to Salem and the 17th Century. And then let us all settle down to the job of moving ahead together, in our own time, without fear, one of the other, and with the good of everyone, each lonely individual in our country, firmly held in mind.

Just one month later, Bradbury got into a heated exchange with the left-leaning journal the California Quarterly, which had rejected a story he had submitted, not due to any lack of literary merit but because its contents didn’t sufficiently toe the magazine’s ideological line. Bradbury’s “thunderous” response (Eller’s description) deserves to be quoted at length:

I do not want to read a magazine edited with your bias, for I do not believe in tampering with other people’s philosophies. If a story is good, it is good, if bad it is bad. You completely neglected to say in your letter whether my story was good or bad. Jesus! If you edit all your stories this way, God help your writers. I, praise the Lord, will not be one of them. . . . I shall continue to fight for the things I believe right. . . . I shall oppose any damnfool thing we do as a country, and anything Russia does as a country. I shall go merrily on with my flag which bears a snake and which reads: Don’t tread on me. May the California Quarterly collapse within the coming year.

The political right and left’s willingness to suppress free expression in the interest of pursuing an agenda underpins the plot of Fahrenheit 451, in which firemen of the future are tasked with burning books along with the houses that harbor them. As Daniel J. Flynn observed in a 2012 profile of Bradbury for The American Conservative:

The obvious reading of Fahrenheit 451 reveals a story about censorship. This view lends itself to competing left-right interpretations, making Fahrenheit 451 the unique politically charged book that transcends the controversies of its day and finds welcome in conflicting political camps. Is it about McCarthyism or political correctness? The flexibility of political readings helps explain the 5 million copies in print.

But Flynn notes a deeper theme: the prediction that an America capable of such measures would arrive at that crossroads not through a totalitarian political takeover but due to the mass adoption of consumer technology. Writing decades before the invention of the personal computer, Bradbury accurately predicted reality television, mobile devices, virtual reality, and the issues of addiction and suicidality, alongside the loss of the ability to read deeply and think critically, that would result from a society turning collectively toward these soul-traps. As Beatty, the fire chief, explains to the novel’s protagonist, the demise of books “didn’t come from the Government down. There was no dictum, no declaration, no censorship, to start with, no! Technology, mass exploitation, and minority pressure carried the trick, thank God.”

The Fahrenheit-era letters in Remembrance underscore this point. “The great centrifuge of radio, television, pre-thought-out movies, etc. gives us no time to ‘stop and stare,’” Bradbury writes to the author Richard Matheson in 1951. “Our lives are getting more scheduled all the time, there’s no room for caprice, and caprice is the core of man, or should be the tiny happy nucleus around which his mundane tasks can be assembled.”

In a later dispatch to his agent, Don Congdon, Bradbury conveys his excitement at finding the themes of Fahrenheit echoed in the work of the influential technology critic Lewis Mumford and the Revolt of the Masses author José Ortega y Gasset. And yet Remembrance reveals some internal waffling on technology. It may have been easier for Russell Kirk, with his distance from the gadget-curious world of science fiction (and Los Angeles) to remain steadfast in his tech-skepticism. But while he and Bradbury both refused to drive, shunned television (though Bradbury eventually relented), and preferred typewriters to computers, Bradbury couldn’t wholly shed his childlike “gee-whiz” reaction to shiny new objects. In a 1974 letter to the BBC documentarian Brian Sibley, Bradbury seems to have shrugged off the disconcerting warnings of Mumford, Ortega y Gasset, and his own work to declare, “I am not afraid of robots. I am afraid of people, people, people. . . . Robots? God, I love them.” Which puts Sibley in the awkward position of responding with the sort of blinders-off argument Bradbury the fiction writer might have employed: “I can’t agree with all you say about robots (though I love the way you say it) because I think the one flaw in your philosophy is that it is the people you fear who control the robots you trust, and therein lies the danger.”

Bradbury’s views on space travel went through similar contortions. The Martian Chronicles (1950) predicts a number of tragic consequences for humanity’s attempts at space colonization, and a 1958 letter to the art critic Bernard Berenson conveys a lingering ambivalence as the Space Age loomed:

I would prefer that space-travel waited on the maturity of man. But since it is obvious we children are going into space, regardless, I can only hope that it will eventually turn into a United Nations Project. The Idiot jumps at the stars. With myself half in that Body and half-out, and with others like myself, perhaps the whole thing won’t come to complete ruin.

But once space exploration actually began, the child in Ray Bradbury—never far from the surface—won the day. (Perhaps, too, the realization that there was no life on Mars—hence no native culture under human threat—eased some of his concerns.) The urge to get into the mix—to advise, cheerlead, and occasionally caution NASA—proved impossible to resist. And how could it be otherwise? This was, after all, the future he had been thinking and writing about since childhood. Inevitably, his creative output slowed as “Ray Bradbury, Professional Visionary” began to crowd out “Ray Bradbury, Fiction Writer.” Bradbury penned nonfiction paeans to space exploration in Life and other outlets, hosted the 1979 ABC TV documentary Infinite Horizons: Space Beyond Apollo, and participated in the creation of the “Spaceship Earth” ride for Disney’s Epcot Center. He continued to write stories and novels, but there are noticeably fewer letters in the collection from these later years.

Jonathan R. Eller is to be commended for his editorial discernment, his doggedness in tracking down far-flung correspondence, and his success in procuring permissions for the many incoming letters. The structure of the collection is unique; instead of proceeding chronologically, Eller has opted to organize the book into themed sections: “Mentors and Influencers,” “Literary Contemporaries,” “Filmmakers,” “Editors and Publishers,” “Agents,” “War and Intolerance,” “Recognition,” and so on. The result is a literary mashup of Groundhog Day and Rashomon in which we keep cycling back to key moments in Bradbury’s journey—the publication of The Martian Chronicles, the writing of Fahrenheit 451, the tumultuous collaboration with John Huston on a Moby Dick screenplay (Huston’s resulting film was released in 1956), and so on—but from different perspectives. Thus, appropriately, the sometimes-stuffy genre of letters has been infused here with the lyricism, attitude, and hallucinatory quality of a vintage Bradbury tale. Along the way we get insights into the private Bradbury, so often obscured by his public persona of eternal Peter Pan crossed with carnival barker. Beneath that colorful surface we find a wide-ranging, if easily distracted, intellect; a gift for friendship (Bradbury’s correspondence with several compatriots, including Don Congdon, Richard Matheson, and Frederik Pohl, spans decades); and a generosity toward the many fledgling writers who sought his counsel.

We also gain insights on Bradbury’s intuition-based creative process, his work ethic, and perhaps his finest quality: a lifelong cultivation of gratitude for being alive, “the one time round in a miraculous experience that never ceases to be glorious and dismaying,” as Bradbury wrote to Kirk in 1967. With the permanent things under continual threat, and with our appreciation of the miraculous seemingly at a low ebb in our materialist era, Remembrance has arrived at just the moment when it would do us all a world of good to remember Ray Bradbury: his past and his futures.