Lord Acton said that great men are almost always bad men. Their greatness, he thought, contributed to their wickedness: power corrupts, and more power is all the more corrupting. This is taken for a truism in the Western world today, and many of our institutions are built on the understanding that as long as power is limited corruption will be kept in check.

The full truth is rather different, however. Power can corrupt, but more often it provides the opportunity for corruption that was already present in the human heart to enjoy a wider expression. In this light, the task of the wise and good is to confront corruption before it rises to power—otherwise institutional or constitutional limits, however well-designed, will prove to be feeble restraints.

Conservatives are fond of quoting John Adams’s remark that “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people,” but they often recognize only half the force of his words. He was not only calling for the upholding of morality and religion but also drawing attention to the Constitution’s weakness. In the same letter of October 11, 1798, he writes, “We have no Government armed with Power capable of contending with human Passions unbridled by morality and Religion. Avarice, Ambition, Revenge or Galantry, would break the strongest Cords of our Constitution as a Whale goes through a Net.”

Elsewhere Adams criticized the Constitution for failing to establish a truly mixed regime: it contained no provision for the institutional representation, and at the same time restraint, of the elite. There was no place created by the Constitution where men who were rich and well-connected from birth could be watched by the public. Instead, the power of the great would be wielded behind the scenes, influencing all the popular channels of government. Adams was not opposed to such influence in itself, but he was alive to the danger that popular government and informal elite power would be mutually corrupting. All that could stand against this possibility was whatever strength remained in religion and moral habit.

Our Constitution, wisely devised though it was, had not solved the problem of the rulers’ character. And in the American context the problem was twofold: the popular nature of government and our highly egalitarian social order meant that the people’s character must be cultivated, while the formally unacknowledged persistence of natural and hereditary elites required an education appropriate for them, too.

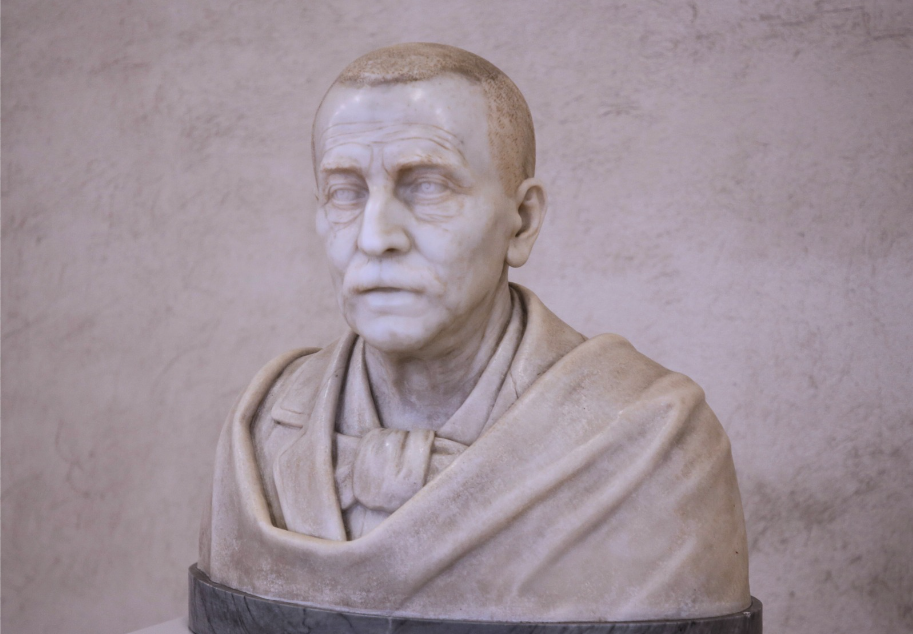

Teaching the great how to be good—to be at once aristocratic and human, even Christian—was a difficult and dangerous undertaking for most of Western history. Socrates died for it. The young blue bloods whose company he kept were in many cases a genuine threat to Athenian democracy. Their enemies charged Socrates with corrupting the city’s corrupt youth, and a jury found him guilty of the capital crime.

Socrates had not made Alcibiades vainglorious or Critias ruthless, of course. And while he may not have entertained any illusions of turning them into philosophers, whatever philosophy he could impart had a chance of strengthening their better nature against the worse—or, if it failed with them, such failure could still advance the effort with the next crop of pupils. Socrates knew his own death would drive his lesson home, too.

For two millennia and more afterward, the point of elite education, and royal education above all, was to teach rulers self-control and, where possible, humility and humanity. Mirrors for princes at their best showed the powerful their own faces alongside an image of good governorship, the better to make the one resemble the other. This became a task for drama and other arts as well. (To be sure, the aristocrats of Socrates’ day already modeled themselves after Achilles, but Plato thought they learned the wrong things from poetry and its heroes.)

Effective education doesn’t erase the passions, but it directs them to higher ends. Throughout centuries of hereditary rule, the authority of the classical tradition provided a standard for noblemen and rising commoners alike. Power could still corrupt, but there was a worldly tribunal, as well as a heavenly one, before which kings and courtiers alike were judged. It was a tribunal within the well-educated mind, however wicked and rebellious that mind—even a royal mind—might be.

The men who wrote the Constitution were products of this elite education; they might not have had titles of nobility, but they had the learning of princes. They created laws and institutions that would restrain power in the service of popular government by representation. But as successive generations of citizens have adopted commercial and democratic priorities in education, the moral and religious grounding that made republican self-government possible in the first place has eroded. As Socrates showed, a democracy needs aristocratic education in the truest sense, especially for the most talented, fortunate, and politically engaged citizens.

This education cannot be found easily at many of America’s most prestigious institutions of higher education today, which excel in investigations into the physical world but are thoroughly corrupted where humane learning is concerned. In centuries past, vices of the ruling class such as violent pride and casual arrogance had to be curbed. Today the vices of the ruling class have not been curtailed but merely complicated and disguised by the demands of democracy—the old vices are still there, only new and seemingly opposite ones have been placed on top of them. Selfish arrogance hides under self-righteousness, while pitiless disdain takes the form of impersonal compassion, or wokeism. Classical education is a remedy for these symptoms as well as a treatment, if not a cure, for the underlying disease.

Power corrupts, but to restrain power while leaving corruption unchecked—to rely on laws in place of moral education—is to surrender liberty in the long run.