“Everything begins in mysticism and ends in politics.” — Charles Péguy

In the wake of the recent foreign policy debacle in Afghanistan, many have begun questioning the prudence of widespread U.S. interventionism in world affairs. The syndicated columnist Patrick Buchanan poignantly remarked in August, “Not once in this century has the U.S. decisively won one of the wars it launched—in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Yemen or Libya.” A week after he wrote that, the U.S. Army’s UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters departed Afghanistan for the last time, in an international crisis replete with images that evoked the 1975 Fall of Saigon. And as Kabul fell to the Taliban and thousands of men, women, and children—including 100–200 American citizens—were left to broker their fate in a land of chaos, our statesmen and military leaders and the American people at large pondered the wisdom of a foreign policy that could end so poorly.

Lest we forget, Afghanistan is but the latest in a series of U.S. military interventions with troubling track records. The 2003 invasion of Iraq to depose Saddam Hussein and establish a pro-Western government destabilized the Middle East, and the 2012 withdrawal of U.S. forces from the country created a vacuum that precipitated ISIL’s rise to power. The U.S.-supported removal of Jean-Bertrand Aristide as Haiti’s president in 2004 shook the island nation and compelled the use of United Nations peacekeeping forces in the country until 2017. U.S. military efforts to quell unrest and fight terrorism in Somalia in 2007 lasted a decade and a half, cost billions, and ended in a stalemate. The military bombing of Muammar al-Qaddafi’s forces in Libya in 2011 instigated the Second Libyan Civil War and destabilized northern Africa. And U.S. clandestine support of Syrian rebels beginning in 2012 perpetuated a civil war that has claimed a half-million lives to date.

What drives our consistent recourse to interventionist campaigns that fail? Was each of these international situations unique, or is there a common theme underlying our foreign policy decisions and behavior? The French essayist Charles Péguy said everything in politics can be traced to philosophical belief, reframing an ancient teaching of Plato and Aristotle that politics reflects the disposition of the human soul. A search for the root cause of our foreign policy failures should, therefore, begin with an examination of the philosophies and ideologies that are guiding our leaders.

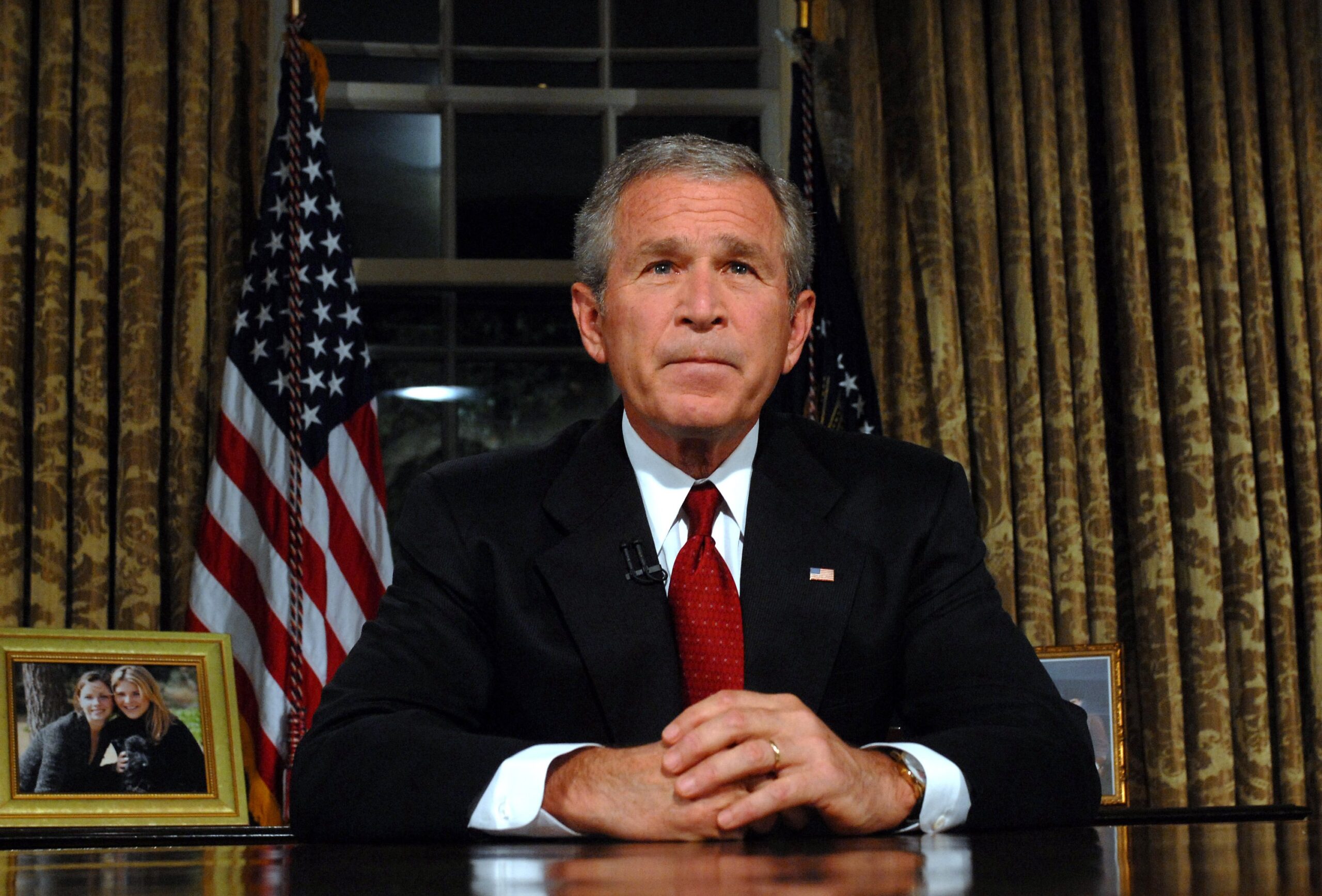

Two chief paradigms have predominated U.S. foreign policy in the post-Soviet era. The first, neoconservatism, professes that states act in their own self-interest to maximize power, and asserts that security in an antagonistic and anarchic world requires bold and unconstrained engagement in world affairs to coerce and overcome one’s adversaries. This philosophy often compels an aggressive interventionism, prompted by the need to attain or extend regional or global primacy. Neoconservatives with their bias for action tend to see the world as a zero-sum game with winners and losers, and they affirm that losing is not an option. This approach guided decision-making after 9/11 during the George W. Bush administration as leaders enacted forceful interventionist campaigns to remove Saddam Husseain from power, overthrow the Taliban in Afghanistan, and expand U.S. influence in the Horn of Africa and elsewhere. The paradigm tends to generate its own ethic: because gaining an upper hand in world affairs is paramount, neoconservatives often subjugate human reason to the human will, concluding with Hobbes that “nothing can be unjust” in politics and with the Athenians at Melos that “might makes right.” Their use of force to secure power frequently engenders discord and strife—and as ethicist Michael Walzer reminds us in Just and Unjust Wars, “Aggression opens the gates of hell.”

The second paradigm that has prevailed in U.S. foreign policy since the fall of the U.S.S.R. is neoliberalism, often called “liberal hegemony.” This theory claims that by projecting values such as human rights and democratic governance, the community of nations will promote mutual interests, overcome anarchy, and engender unity and peace. International institutions play a lead role in this enlightened transformation by resolving conflicts, propagating liberal ideals, and inspiring change. By following such a plan, neoliberals expect the world to collectively reach what Francis Fukuyama called the “end point of mankind’s ideological evolution.”

However, as they aspire to remake global society, they inevitably find themselves depending on interventionism as well, either supporting revolutions and upheavals in foreign lands to make way for the Western liberal vision or directly intervening in countries to impose it—something Nobel laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn called in his 1978 Harvard commencement address a “persisting blindness of superiority.” Neoliberalism dominated foreign policy during the Obama Administration as leaders engaged in “nation building” in Afghanistan and Iraq, supported “Arab Spring” uprisings in Libya and Syria, and relied on institutions like the United Nations to generate clout and support. This philosophy also has an ethic: because it presumes to hold liberal values in highest esteem, any methods that neoliberals devise to promote “American exceptionalism” abroad can be deemed just and praiseworthy, a dangerous claim whose genesis is pride.

A dissenting paradigm called neorealism, or “structural realism,” occasionally enters the policy debate but typically is unheralded outside of academic circles. This view tends to advocate caution in international affairs, preferring to engage selectively and only when national interests demand. Neorealists seek to balance power among states in the international system as a matter of prudence. Their aversion to aggressive intervention and the costly use of military force has marginalized them in foreign-policy discussions since the mid-1990s, when statesmen sought to reset the world by exploiting U.S. unipolarity and began to pursue an increasing militarism that has come to define 21st century U.S. statecraft.

Neoconservatives and neoliberals see the world differently and have divergent goals. But they ultimately end up in the same place, wrestling with other nations for power on the world stage. Interventionism is their common tool. Noticeably absent in their philosophies is an appeal to a higher moral law beyond the self. Rather than heeding the moral wisdom of the ages, they opt either to reject ethics as irrelevant (neoconservatism) or self-define what is right and how we must act to attain it (neoliberalism)—leading them to a tenuous morality that T. S. Eliot once called “dreaming of systems so perfect that no one will need to be good.” Even the dissenting voice (neorealism) stubbornly insists on an amoral posture, refusing to acknowledge ends higher than the furtherance of the state.

Lost in all of these modern international relations theories is a deference to enduring moral principles that transcend time and place, or the mandates of virtue, spawned from human nature, that call upon mankind to do good and avoid evil always and everywhere. Forgotten too is the true purpose of war and conflict, which is to achieve a lasting peace. Realigning U.S. foreign policy with traditional ethics would yield very different outcomes in international affairs, ones marked by prudence, justice, restraint, courage, and just warfighting. Scholar Daniel Mahoney has termed this approach “statesmanship as human excellence.”

Would this new foreign policy stop interventionism? By no means. In a fallen world, security threats will persist, and America will clash with her enemies when deterrence fails. But a foreign policy vested in the tenets of moral virtue and the common good would ensure we intervene selectively, prudently, justly, and only as a last resort. It would also recognize the folly of putting our men and women in harm’s way to fight for dubious objectives that embrace power politics over goodness. It would keep ethics front and center.

Afghanistan is over, and the troops have come home. The time for a reorientation is now. If instead our statesmen continue to adhere to the same flawed political philosophies, we might as well prepare for the next ruinous intervention. You can be sure it’s coming soon.

Joseph B. Piroch is a U.S. Air Force Fellow at RAND Corporation.

Daniel A. Connelly is an assistant professor at the Air Command & Staff College and a retired U.S. Air Force intelligence officer. The views and opinions expressed or implied are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of the Air Force, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government.