Oh, to be a cat! Who hasn’t had that thought, looking with admiration at a sweetly snoozing puss, its every need satisfied by an adoring owner? Is there any animal that can seem more contented than the cat? John Gray is here to tell us we can live more like fussy felines—and, indeed, that we should. It turns out that Gray, one of the most skeptical of recent thinkers, has settled on something to embrace.

Over the course of an academic career that included stints as professor of politics at Oxford—where he received his doctorate—and of European thought at the London School of Economics, Gray wrote studies of John Stuart Mill, Friedrich Hayek, and Isaiah Berlin, among other works. His own political views famously shifted: the young Gray was, like many in his milieu, a Labour Party supporter. He became a rebel in the academy when Margaret Thatcher brought him over to the Conservatives. By 1987 he decided that her New Right had become the sort of “universal project” he saw as not just naive but downright dangerous.

He then moved back to the left before coming to the same conclusion about that crowd. Now the philosopher, himself an atheist, might best be described as an iconoclast who sees secular humanism every bit as mythmaking as religious belief.

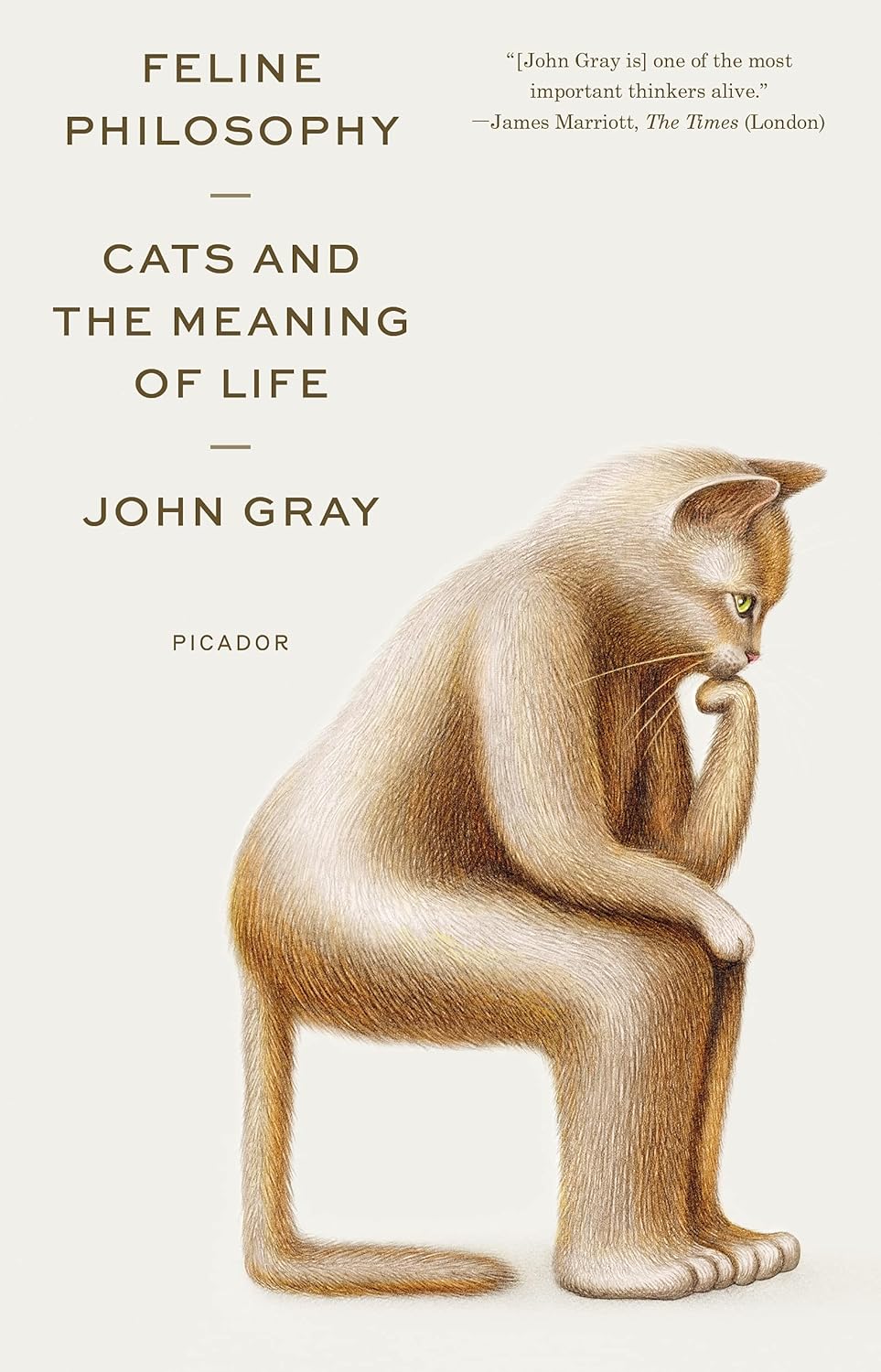

Gray has never shied away from controversy, but perhaps leaving the ivory tower has made him feel even freer. Would the seventy-two-year-old have published his latest book while an LSE professor? As Gray readily admits in Feline Philosophy, “A book on cats and philosophy is an unusual enterprise.”

Gray’s work is no analytical argument like Thomas Nagel’s pioneering paper “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” There’s plenty of philosophy here, from the pensées of Pascal to the problems of Plato. But Gray considers cats in myth, memoir, literature, and history, too. In confident, dare I say feline, prose, Gray has written a book as curious as its subjects, one that seems the culmination of his two longtime loves: cats and tearing down tendentious theories.

He begins with an anecdote that illustrates these goals perfectly. “A philosopher once assured me he had convinced his cat to become a vegan.” Gray, as always, is skeptical—and here rightly so, finally discovering that the carnivorous cat regularly ventures outside the home, where no doubt it enhances its diet. The man “only showed how silly philosophers can be. Rather than trying to teach his cat, he would have been wiser if he had tried learning from it.”

“Cats have no need of philosophy,” Gray insists. “The source of philosophy is anxiety, and cats do not suffer from anxiety unless they are threatened or find themselves in a strange place. For humans, the world itself is a threatening and strange place.” Religion and philosophy, he says, both “try to fend off the abiding disquiet that goes with being human.” Cats never have existential crises: “Obeying their nature, they are content with the life it gives them,” Gray writes. “That may be the chief reason many of us love cats. They possess as their birthright a felicity humans regularly fail to attain.”

But there’s more to them, too, as surely Gray knows, having had cat companions for thirty years. (His last, a Birman named Julian, died at twenty-three after he completed this book.) Cats are notoriously independent and resistant to authority. These are attractive qualities to a human race that has so many people to answer to throughout life. They can be standoffish, and their playing hard to get only makes their attention, when they deign to dole it out, more worth it. But they are also easily amused, the only tools required are a little laser pointer, a piece of yarn, or just a workaday cardboard box.

As Gray points out, the singular character of cats has led humans not only to worship them but also to fear them. “So beguiling are they that cats have often been seen as coming from beyond this world,” he writes. That wasn’t always to positive effect. “Cats were buried alive under the floorboards when houses were built, a practice believed to confer good fortune on those who lived there” in early modern France.

Cats’ bad luck wasn’t limited to that country. “During pope-burning processions in the reign of Charles II, the effigies were stuffed with live cats so that their screams would add dramatic effect,” Gray writes. “In Germany the howls of cats tortured” during festivals “was called Katzenmusik.” For Gray, such rituals express the resentment of “misery-sodden human beings redirected against creatures they know are not unhappy.”

Some philosophers were just as cruel. René Descartes reportedly “hurled a cat out of a window in order to demonstrate the absence of conscious awareness in non-human animals.” He then proved the failure of rationalism by concluding that “its terrified screams were mechanical reactions.”

Perhaps Gray is right when he says, “Instead of being a sign of their inferiority, the lack of abstract thinking among cats is a mark of their freedom of mind.” They never get stuck trying to fit the facts into an ill-suited theory; they accept facts as facts and move on.

Gray contends that philosophers could learn something from cats. Rather than taking the world as it is, they often invent elaborate justifications for “local prejudices.” Gray’s criticism might work for certain targets. But it is an odd suggestion to make just before beginning a discussion of Spinoza, whose radical rationalism got him expelled from his family and community. One gets the impression Gray wasn’t a popular figure in the faculty lounge, either.Gray admires philosophers who display feline wisdom. He finds that Montaigne has a “better understanding of cats, and of the limits of philosophy,” than just about anyone else. Montaigne thought, to use Gray’s formulation, “Philosophy was useful chiefly in curing people of philosophy.” Among other things, that means curing them of the idea that we have nothing to learn from what we have thought of as lower creatures. As Montaigne wondered, “When I play with my cat, who knows if I am not a pastime to her more than she is to me?”

Other cat-loving thinkers were more sociable than the reclusive Montaigne. Take Samuel Johnson. Like Montaigne, “a devoted cat-lover” who “suffered from attacks of melancholy,” Johnson would “walk into town to buy oysters for Hodge, his black-furred feline companion, and valerian to ease the cat’s pain when it was ill.” (A charming statue of Hodge stands in the courtyard of Johnson’s London residence, now a museum.) The prolific Johnson obviously spent much time alone, but he “mocked the belief that happiness could be achieved by thinking about the best path in life.” One can’t even know the best path in life. As he wrote to that almost constant companion James Boswell, “To prefer one future mode of life to another, upon just reasons, requires faculties which it has not pleased our Creator to give us.”

In seeking an escape from fruitless contemplation, “Johnson was at one with his contemporary David Hume.” Gray thinks “the two had little else in common”—“Johnson was a believer, Hume was not”—but they were both sharp skeptics who distrusted grand schemes to rebuild society. And Hume, too, faced down depression, his doubts giving him what he called a “philosophical melancholy and delirium.” How did he dispel it? “I dine, I play a game of backgammon, I converse, and am merry with my friends; and when after three or four hours of amusement, I wou’d return to these speculations, they appear so cold, and strain’d, and ridiculous, that I cannot find in my heart to enter into them any further.” One might say that living gave Hume the will to live.

Conversation and cats—our need for one or the other, and preferably both, proves no man is an island. But is a cat? Is living “in contented solitude” the lesson we should take from our feline friends? Gray often offers a too-narrow view of the beasts. Since domestication around ten thousand years ago, cats have lived “in close quarters with humans,” he writes, “without their wild nature changing greatly,” unlike dogs. But it was cats, not humans, who initiated domestication. As humans began to store grain that attracted rodents, cats saw an opportunity for easy pickings. Cats do more than just eat and sleep, however—a human can be more to a cat than simply a can opener.

Gray says that unless confined within unnatural environments, “cats are never bored. Boredom is fear of being alone with yourself.” Did Gray never have a cat who seemed a little out of sorts? My cat, Wimsey, sometimes is. In those situations not even his favorite treats tempt him. He wants me to play or perhaps just settle in somewhere there’s a spot for him, too. “If we treat them with respect, they grow fond of us, but they will not miss us when we are gone,” Gray insists. Perhaps. But my cat sometimes wakes me up in the night and not for food; he’ll demand a series of chin rubs before I can go back to sleep. Wimsey sleeps next to me and, almost without fail, greets me every time I come home. Gray mentions the philosopher of language Ludwig Wittgenstein, but there’s one gaping hole in his book: he doesn’t mention cat language and how felines developed vocalizations to communicate with humans.

Gray has written a beautiful book, but is it one that will put the philosophers out of business? He’s right that cats take us out of ourselves and that there’s much we can learn from their “fearless joy.” As he advises in “Ten feline hints on how to live well,” a section near the end, “Forget about pursuing happiness, and you may find it.”

Cats are content with their nature, but the search for meaning is part of human nature. We’re unhappy not because we’re mortal—cats are, too—but because we know we’re mortal. “Careers and love affairs, travels and shifting philosophies are twitches in minds that cannot settle down,” Gray writes. What twitches! They’ve given us the transcendent music of Bach and the inconceivably wise words of Shakespeare, among much else.

Yes, we should learn to live in the moment, like our fascinating feline friends, and to recognize that human beings can’t come by certainty. Those who claim to possess it have led us not to happiness but to hell on earth. Gray doesn’t mention Karl Popper, but the philosopher of science and politics well understood that we must live with uncertainty even as our nature rebels against it. Curiosity might have killed the cat, but it’s led humans to great highs as well as lows. So remember to bring yourself back down to earth now and then. Contemplating a contented cat will help.

Kelly Jane Torrance is a New York Post editorial board member.