What does it mean to be American? One might be inclined to look to the Capitol Rotunda, the engravings of monuments in Washington, D.C., or the Federalist Papers to find an answer to that question. But maybe Oklahoma City is a better place to start.

Bruce P. Frohnen and Ted V. McAllister devote a chapter of Character in the American Experience to the settlement of Oklahoma City beginning in 1889. Unlike many earlier American settlements, it was disorderly and not immediately community-based. There was no solemn charter signed by like-minded citizens binding themselves to one another in the sight of God. Self-interest largely directed events, along with the regulatory impulses of an increasingly assertive federal government looking after special interests. There were plenty of scoundrels and cheats too.

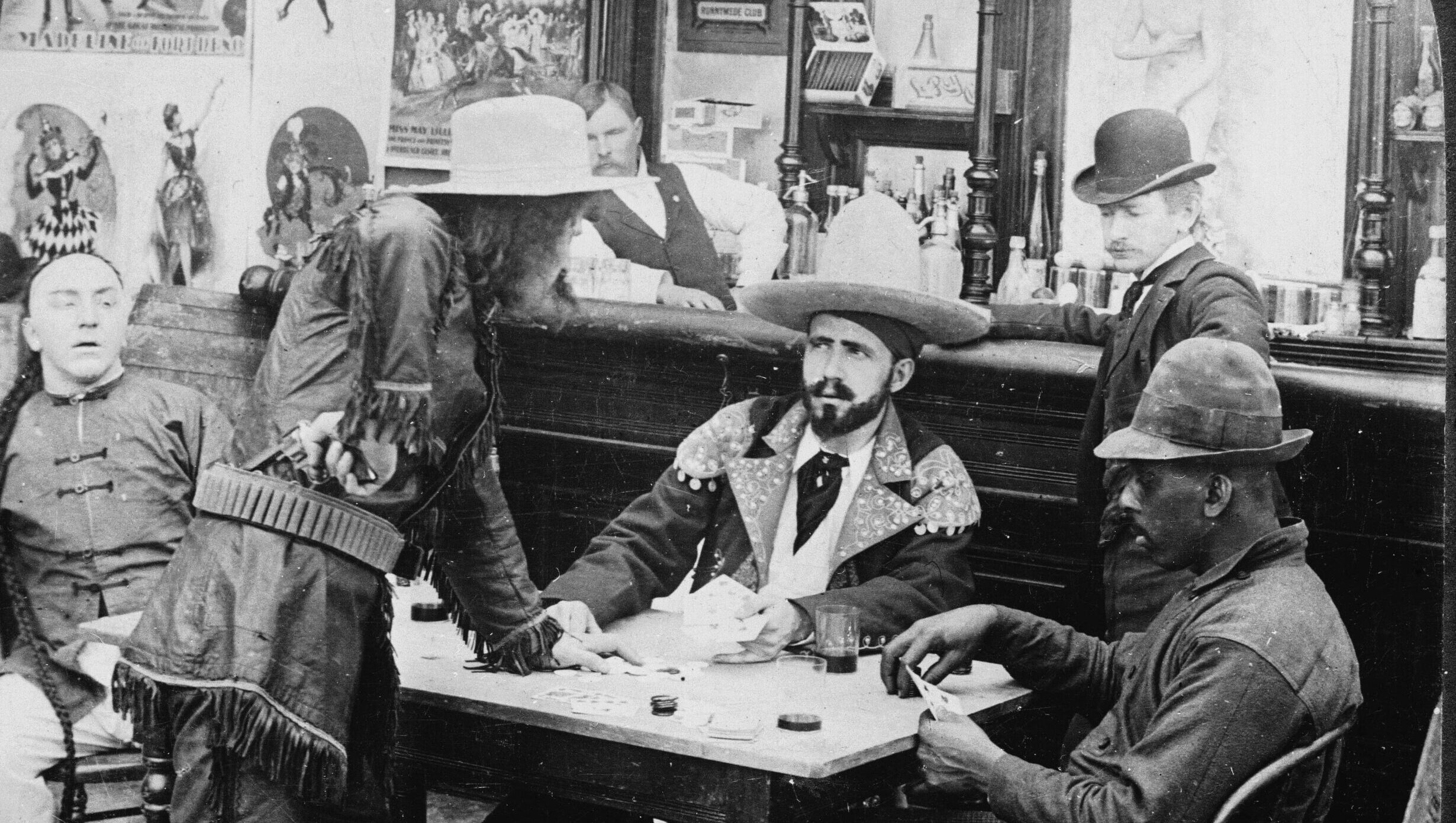

But amidst the chaos of the famous “Land Rush,” and amidst the cheaters, shysters, and power brokers, an impulse toward orderly community emerged. People found ways to balance the influence of the powerful: “Good citizens . . . kept their heads and (mostly) kept the peace as well.” And many of the bad ones eventually became “domesticated”—even as others got away with their schemes and profited heavily. Without any mythical Founder of surpassing virtue, Oklahoma City spawned churches, schools, charities, citizen planning committees, and local democracy. Eventually, the con men were even woven into the city’s (and state’s) folklore.

The Oklahoma City experience may not be an ideal model of American community, or the most representative example. But it reveals the power of Frohnen and McAllister’s subject: the character of the American people as it manifests in a specific experience.

No shortage of ink has been spilled on the question of American identity, especially in recent years as it has become clear that there is no reviving the idealized postwar consensus of the mid-twentieth century. This book is somewhat different. In this second collaboration between Frohnen and McAllister—the latter of whom sadly passed away last year—character is the subject, not agreement on ideas or a uniform culture (though both ideas and culture, of course, exert influence on character). Frohnen and McAllister identify certain qualities that revealed themselves throughout American history in different places and contexts. This character is forged not by a shared ideology or blood but by shared experience—by citizens’ relationships with one another and the things they’ve done together.

Accordingly, the authors do not put much emphasis on uniformity and sameness in terms of substantive commitments. They do point to some factors that made common life together easier: the shared English language, Protestant Christianity (recognizing the wide variety within that category), the English common law, and the traditional “rights of Englishmen.” But they do not attempt to isolate any of these to make it the defining characteristic of what it means to be an American, nor do they put them all together into a stew and call it a definitive national identity:

Whether these areas of commonality were greater than the myriad of differences is not as important as most people assume once we understand that American culture—the common ground that made nationhood possible—depended just as much on the depth and nature of American pluralism as it did on these four shared cultural traits.

Indeed, they argue that Americans have, counterintuitively, been “bound together as much by mutual distrust as by a common and shared national culture.”

How can difference and distrust bind a people together? The short answer is “local self-government.” Americans have shown themselves to be a communal people who are also deeply averse to being ruled by others—including other Americans. They have been inclined to find ways to “get on” with one another, even while jealously guarding their distinctiveness. This “unruly” character is the primary theme of the book, producing a politics defined by a “pattern of cooperation, competition, and low-level conflict.”

This character is forged not by a shared ideology or blood but by shared experience—by citizens’ relationships with one another and the things they’ve done together.

By “low-level,” the authors mean clashes not over grand ideological visions or rival attempts to remake the world in one way or another. Rather, American political conflict has mostly been “rooted in disagreements over what practical steps were necessary for peace and prosperity in the specific circumstances of particular communities.”

As readers of Frohnen and McAllister’s previous collaboration, Coming Home, would expect, the picture is markedly localist. Challenging both the individualist and nationalist elements of conservative discourse, they champion strong, self-governing towns, localities, and states that maintain an expectation of citizen involvement in social life and uphold standards of personal public behavior. Some of this translates to local government regulation, but most of it is done through civil society. Powerful, centralized government has proven to be the greatest threat to both local self-government and the distinctive American character it formed.

Their presentation puts one in mind of Schopenhauer’s hedgehogs who have found a way to huddle together for warmth while keeping enough distance to avoid one another’s quills. But in the American context, that “sweet spot” may be calculated differently among different groups of prickly mammals. The authors stress that for most of American history there was little expectation of personal privacy from one’s immediate community. (They relate more than once that drapes on windows are a relatively recent phenomenon—what do you have to hide from your neighbors?) But Americans have still been wary of one another’s spikes, especially those that threaten the freedom to participate in and build up local community.

Those complex social groupings mean that Americans have come up with many “arrangements,” “deals,” and “contracts” for structuring their public life. The authors are keen to point out early on that the notion of “contract” when applied to political and constitutional arrangements should not, as it often is, be understood to connote a “thin” social life. The problem is not so much the contract metaphor itself but the tendency to treat the contract as if it were everything. This is especially true of the U.S. Constitution, which they caution should not be understood as embodying “the hopes, dreams, and . . . ideals of the people.” Americans had hopes, dreams, and ideals, but they were embedded in their social experience, not their charters of government. The Constitution, like other kinds of “contractual” political arrangements, does not define or enforce every social value; it ought to be seen as “resting upon and seeking to support them.”

The majority of the short book consists of a brisk walk through American history that highlights this theme of an unruly, plural people finding ways to order their common life together. It starts with David Hackett Fischer’s classic Albion’s Seed and the English “folkways” that defined the cultural divisions of early America. Local self-government and traditional rights play a leading role in the story of the American Revolution and retain their influence on the American mind through the adoption of the Constitution. Neither romanticizing the past nor dwelling inordinately on its flaws, the narrative offers thoughtful commentary on the rise of Jacksonian democracy, the causes and aftermath of the civil war, the progressive era, the world wars, Sixties radicalism, and further developments up to today.

“Where did it all go wrong?” will undoubtedly be the most pressing question for many readers—and to be clear, the authors do believe it has gone wrong. But not all at once. They point back to the nascent “spirit of party” in the Jacksonian era as a potential turning point: that is when narrow interests began to realize the power of combination and consolidation, which eventually allowed them to go beyond the protection of their own sphere and seek out more comprehensive control of social and economic life. That ability to consolidate power, along with the idea that the national government could be a more efficient and rational “guarantor of the public good” than local communities, gradually undermined the old form of self-government. Eventually, it gave rise to a bureaucratic, technocratic national government that (generally in a corporatist alliance with powerful, nationwide companies) oversaw economic life and redefined American rights and liberties.

There was plenty of resistance to this general trend, but it often did not take productive forms. The authors, for instance, are sympathetic to the late-nineteenth-century populist movement’s motivations, but that movement grasped for counterproductive “solutions.” Seeking to cabin the power of big business, its members placed hope in an overly powerful regulatory government, not realizing that in the long term those two behemoths generally feed off of one another.

Even more surprising—and disastrous—was the student radicalism of the Sixties. Notably, Frohnen and McAllister explicitly reject the increasingly popular understanding that the radicalism of the Sixties was mostly the product of foreign, Marxist ideology. On the contrary, they argue that “like the plants so many youth leaders smoked, the 1960s were largely homegrown,” the product of concentrated power and disappointed expectations. The student protests started with frustration over the cold, technocratic character of modern America and a “romantic” yearning for community. Their reaction, however, was not to recover a healthier concept of communal authority but to lash out against all traditional forms of authority. The final result, therefore, wound up attempting to impose a new kind of social justice on the bureaucratic state rather than finding genuine community and authority in our homes.

Given their complex and nuanced account of American history, it is somewhat surprising that in the final chapters they suggest that today there are two fairly straightforward forces at work: one vision that rejects traditional American self-government and the character that comes with it as parochial, backwards, or hateful; and another that champions it and seeks its revival.

One could be forgiven for thinking that assessment too optimistic—for wondering whether the kind of self-government the authors praise has been so distorted today that even those who mean well are largely uninterested in doing what would be necessary for true recovery. Such a recovery would require a radical rethinking of the way we practice politics today. “We will survive as a people only if the raucous spirit of liberty is greater in the American people than any collective sense of national purpose,” they advise. But wrangling over the “collective sense of national purpose” now seems to be the only game in town. Is there any major political movement today that genuinely seeks “not merely to make the nation itself great, but to tame the nation-state and return it to its proper role of guarding rather than running the communities in which Americans actually [live]”?

Moreover, looming over the end of the book is a gloomy question: When is it too late?

When our government becomes our protector, when we defer to the judgment of administrators and other helping professionals to take care of us in realms we had long controlled ourselves, then the very conditions necessary for honor are destroyed. We become servants of a distant government that gives us what it deems in our best interests. Under such conditions we can no longer have the self-respect necessary for honor; we have given up any meaningful self-rule in favor of ease, safety, and comfort. We have relinquished the obligations that defined our character.

Can one reinvigorate constitutional self-government once the character necessary for it is gone? Can one revive that character without the institutions that shaped it? Is America’s political tradition doomed by that catch-22?

But perhaps the settling of Oklahoma City should give some hope. The American character may not always be plainly visible. Even when vice, avarice, chaos, and disorder seem to reign, that unruly instinct for both order and liberty may still have the strength left to cultivate something better.