One of the most famous scenes in F. W. Murnau’s 1922 silent horror film Nosferatu takes place on a rat-infested ship. All but two of the vessel’s crew have died of plague, and in desperation the first mate descends into the hold to attack the problem with an axe. As he hacks away at the vermin, up from a long wooden box rises a ghastly figure with claws and bared fangs. A vampire! Slowly its deadly arms stretch toward him. The mate shouts for help, but it is too late. The scene is not exactly scary, but it is unsettling, mostly because of the vampire’s knees. When he rises from his coffin, they don’t bend. It is as if he has been lifted up by some external malignancy.

This scene so captivated the director Robert Eggers when he first saw it as a nine-year-old boy that he resolved to recreate Murnau’s whole film. He has been working on that project in some form ever since. In high school, he staged Nosferatu as a play with himself in the lead. He took special care to recreate the ship scene as closely as possible, fiddling with props and special effects so that when he rose from the coffin, he appeared stiff as a corpse. (A friend was stationed underneath, pushing up a wooden board with his legs.) Later, when he matured and became a filmmaker known for his meticulous approach to historical detail, he often fantasized about remaking Nosferatu. But, he indicated, unlike the vast majority of entries in the vampire genre, this one would do it right, true to the spirit of the original masterpiece. Buoyed by the success of his first three films, The Witch, The Lighthouse, and The Northman, he got his chance last year: his Nosferatu was released on Christmas Day.

If only the film were true to the spirit of the original! Alas, it is merely the work of an accomplished fan. Eggers is so awed by Murnau that he can do little more than give the master servile homage. The ship scene is a telling example of this tendency: Eggers keeps it in his version—what would the film be without it?—but he is either too timid or too respectful to attempt the languid horror of the original. In the new version, when the first mate descends into the hold, it is so dim he can hardly see. He begins hacking away at the box. The light flickers, and out of the darkness—only for a split second—a ferocious face snarls and gouges his neck. For those who have no familiarity with Murnau’s version, this jump scare may be effective, but for everyone else, it is disappointing. There is nothing of the original’s grand theosophical horror here, only a cheap thrill.

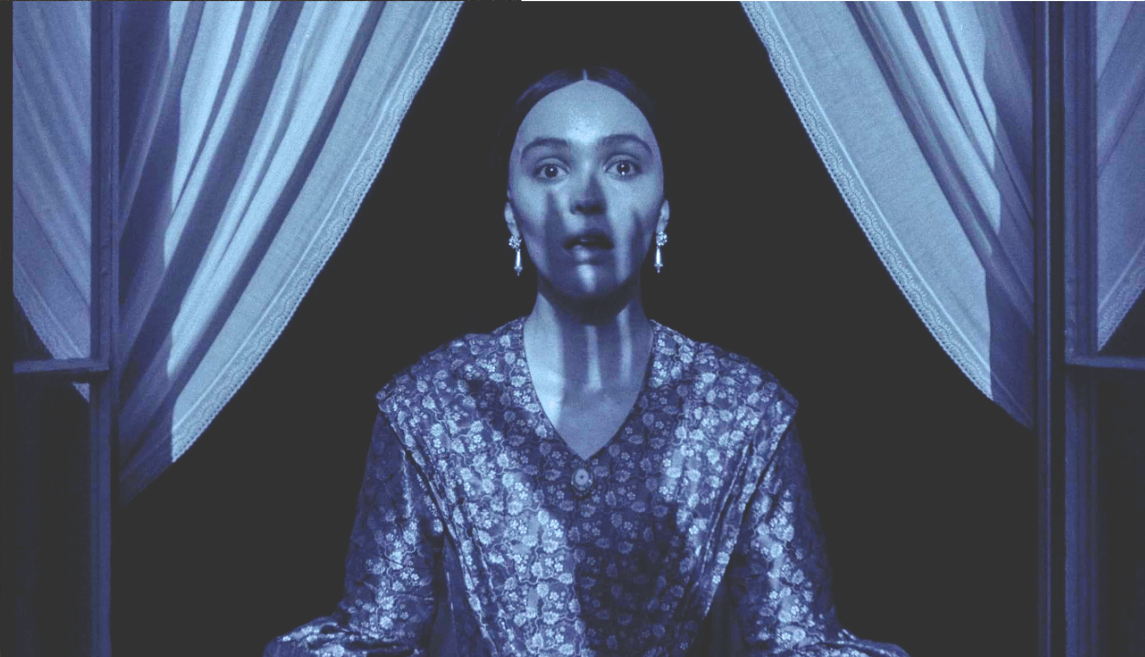

Identifying similar moments of disappointment in the film requires some plot exposition. Murnau’s Nosferatu is loosely based on Dracula, with London swapped for the fictional German city of Wisborg and the character of Count Dracula changed to the more grotesque Count Orlok. Eggers more or less maintains the major plot points: The story begins in the 1830s when the real estate agent Thomas Hutter (Nicholas Hoult) is sent by his employer to sell some land to the reclusive and eccentric Orlok (Bill Skarsgård). Once Hutter arrives at Orlok’s castle in Transylvania, matters quickly go awry, and the count reveals his vampiric nature. Back in Wisborg, Ellen Hutter (Lily-Rose Depp) pines for her husband and is troubled by frightening dreams that become all too real when Orlok descends on the city, bringing with him an army of rats and the plague. Only the Hutters and a motley crew consisting of a doctor (Ralph Ineson), a shipbuilder (Aaron Taylor-Johnson), and a cracked professor (Willem Dafoe) have the knowledge and ability to defeat the count.

There is nothing of the original’s grand theosophical horror here, only a cheap thrill.

In Murnau’s version, Orlok can only be destroyed by the sacrifice of a pure woman’s blood just before the stroke of dawn. Eggers magnifies that requirement such that what was subtly indicated in the original becomes explicitly depicted in the remake. The new Nosferatu is a psychosexual drama, where Ellen’s strange dreams are transformed into a perverse and lifelong yearning for le petit mort under the command of Death himself. “I’ve never been as happy as that moment when I held hands with Death,” she confesses of a dream to Thomas early in the film—and then to everyone else who will hear her out. Again and again, Eggers beats his audience over the head with an old truism—that sex and death are inextricable in the experience of human life—right up to the film’s last frame, where he literalizes the idea with the naked and bloodied body of Orlok intertwined with the pure and milk-white one of Ellen.

By bringing this idea so crudely to the center of the action, any delicacy in Nosferatu is lost to brute eroticism. Worse, it reveals Eggers as something of a try-hard. He seems desperate for his audience to know that he did his research, not only that can he recreate the look and sound of German society before the Revolutions of 1848 but also that he can inhabit the sexual preoccupations of the German Expressionists—what Leonard Woolf called “the second eating of the apple on the tree of knowledge.” The result is a showy but uninteresting film, the work of an overeager student lost in the library’s archives.

Yet there is one very short scene that almost makes up for the film’s faults. In the original Nosferatu, Orlok buys a house across the street from the Hutters. At night, he reaches his arm out for Ellen, and, in a trance, she reaches back. Eggers reimagines the scene in a grandiose way: Orlok buys a dilapidated mansion across town from the Hutters, and when he extends his arm, he casts a long, spidery shadow over the whole city, bringing death and despair wherever the darkness falls. This, too, is borrowed from Murnau, but from his adaptation of Faust, in one of the film’s first scenes, where Satan raises his black wing over the city, and the plague rains down on its inhabitants. Long shadows, the devil extending his dominion over the earth—this is one of the most powerful depictions of evil on film, whether in Faust or Robert Eggers’s Nosferatu. It’s the shadow, more than the substance, that frightens.