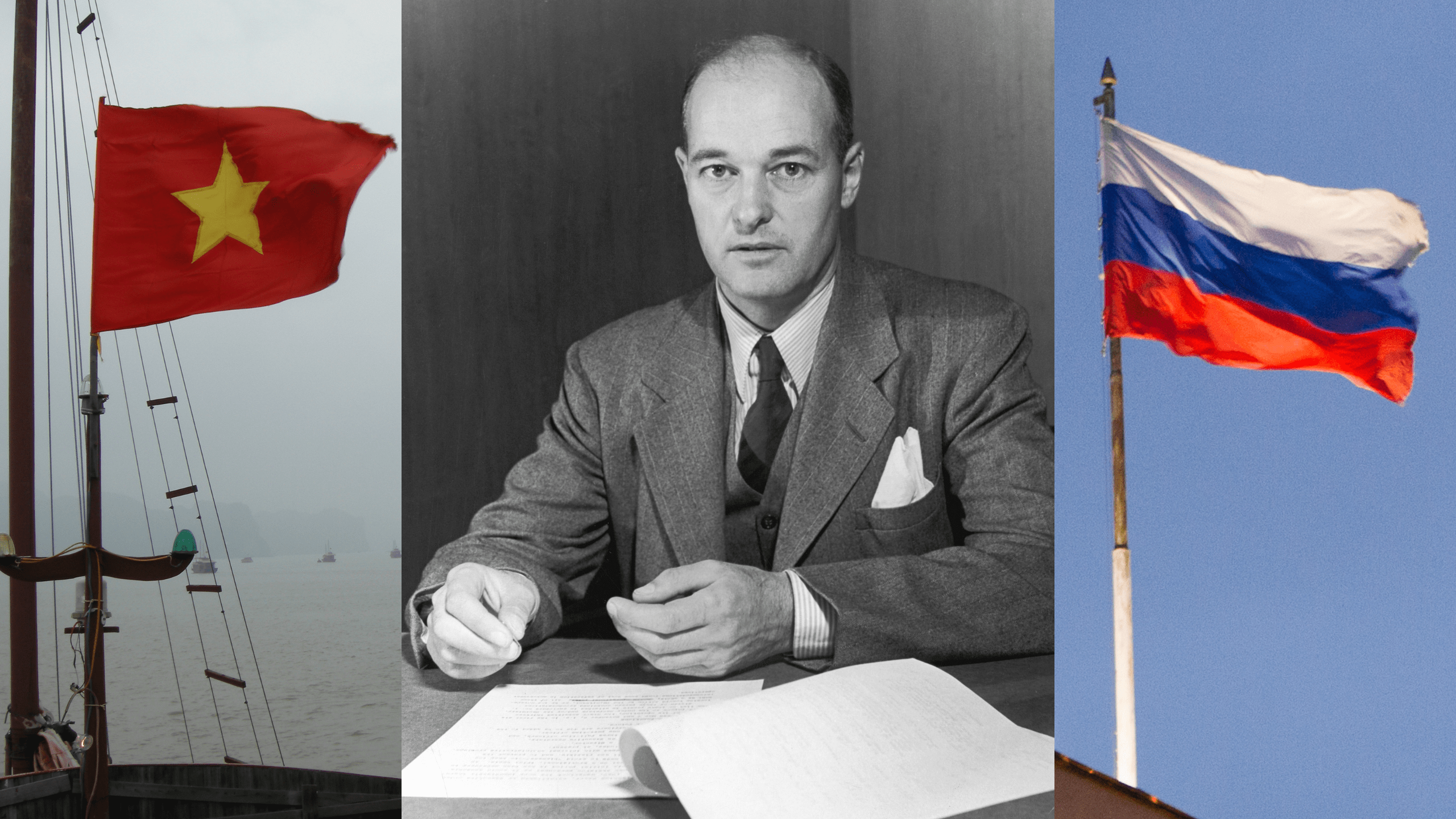

In 1946 George Kennan wrote and at substantial risk to his career in the Department of State arranged to have published anonymously his evaluation of the sources of Soviet behavior.1 His conclusions later were translated into policy for the United States by the Truman Administration. The “containment policy” was born in the series of startling pronouncements by the United States government between 1947 and 1949.

In retirement from government service in the late 1960s, Kennan, discouraged by the direction of United States foreign relations and appalled at another war, began to write again about his original thesis.2 He concluded in 1966 and 1967 that his proposals and analysis had been misinterpreted by U.S. policy officials, overextended because the use of military force was never recommended, and misdirected in eventual application in Southeast Asia.3 The thesis of this paper is that Ambassador Kennan was prescient in his original analysis and conclusions. He was brilliant in redirecting U.S. foreign policy along a path which, after twenty-eight years, has proved to be the right one. Furthermore, the Vietnam War is the best evidence that his policy analysis was sound.

In his original work, Ambassador Kennan described the fanaticism of the Russian revolutionary leaders who “doubtless believed . . . that they alone knew what was good for society . . .” and were convinced that the accomplishment of the revolutionary goals was possible once their power was “secure and unchallengeable.” Writing in 1946, he concluded that the Soviet leaders had been unable to complete the process of political consolidation to “make absolute the power which they seized in November 1917. . . .” While engaged in this process, the Russian leaders were faced with a hostile outside world based in part on their ideology.

Kennan wrote:

. . . there is ample evidence that the stress . . . or the menace confronting Soviet society from the world outside its borders is founded not in the realities of foreign antagonisms but in the necessity of explaining away the maintenance of dictatorial authority at home. . . .

Thus, an external enemy was essential to the maintenance of an internal “state of siege.” He suggested that such a premise of Russian behavior would not permit any “sincere community of aims” with a capitalist state, an enemy who is without honor. Kennan noted that there would be times when the needs of the Russians for capitalist state assistance would alter their public behavior. He warned against those American “Cassandras” who will “leap forward with gleeful announcements that the Russians have changed . . . . But, we should not be misled by tactical maneuvers. . . .” It was his belief that the United States could expect to encounter great difficulties in dealing with the Soviet Union for a very long time.

Kennan revealed the nature of Russian policy reversals by explaining the principle of “infallibility” of the Kremlin which rests on the “iron discipline of the Communist Party.” This he said, permits the leadership to put fourth any particular thesis which they find useful to the cause with a certain knowledge that the faithful would accept and obey the government.

Thus, the Kremlin has no compunction about retreating in the face of superior force. . . . Its political action is a fluid stream which moves constantly, wherever it is permitted to move, toward a given goal. Its main concern is to make sure that it has filled every nook and cranny available to it in the basin of world power. But if it finds unassailable barriers in its path, it accepts these philosophically and accommodates itself to them. [Emphasis added by this author.]

Kennan suggested that the difficulties of the United States in dealing with this ideological and philosophical management of expansive national power would be very different from dealing with a Hitler. Russia was far more sensitive to contrary force, he said, and able to yield when such force was felt to be too strong; yet Russia will not be “easily defeated or discouraged.” Only by intelligent long-range, policies on the part of Russia’s adversaries, applied with patience and persistence and resourceful in their application, Kennan wrote, can the Russian threat be contained. Thus, “the main element of any United States policy toward the Soviet Union must be that of a long term, patient but firm, and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies. . . .” Such a policy, Kennan explained, requires that the United States “remain at all times cool and collected,” but more importantly that the demands made on Russia be set out in a sufficiently careful manner so that Russian compliance does not seriously damage Russian prestige. Russia must never be backed into a corner where compliance means surrender, for war would be the logical outcome of such policy.

Kennan reiterated, “Soviet pressure . . . can be contained by the adroit and vigilant application of counter-force at a series of constantly shifting geographical and political points. . . .” If such a policy, “to contain Soviet power,” were pursued by the Western world over a period of ten to fifteen years he projected a peaceful accommodation for several reasons. First, the terrible cost of human life, hopes, and energies in Russia as a rigid dictatorship pursues its expansionist policy will undermine the will of the people and the principle of infallibility. Such deprivation will leave its mark on the over-all capacity of the next generation to perform for the state. Secondly, Kennan said that Soviet economic deficiencies would become more pronounced and the state more vulnerable; eventually an accommodation with the hated capitalist world would be required.

The analysis inevitably leads to the conclusion that Russia, weaker than the United States, contains systematically the seeds of its own destruction, unless its goals and perhaps the system are modified. Thus, Kennan said, the United States should enter with confidence “upon a policy of firm containment designed to confront the Russians with unalterable counter-force at every point where they show signs of encroaching upon the interests of a peaceful and stable world. . . .”

Kennan warned, though, that such a policy would require leadership of a United States,

which knows what it wants, which is coping successfully with the problems of its internal life, and with the responsibilities of a World Power, and which has a spiritual vitality capable of holding its own. . . . By the same token, exhibitions of indecision, disunity and internal disintegration within this country have an exhilarating effect on . . . [Russia.]

Thus, Kennan believed that the ultimate success of a U.S. peace policy really would rest in full measure on the country itself. He said that the issue of Soviet-American relations was

in essence a test of the overall worth of the United States as a nation. . . . To avoid destruction the United States needs only measure up to its own best tendencies . . . and (accept) the responsibilities of moral and political leadership. . . .

The successful translation of this analysis into practical policies in the European arena from 1947 through the 1960s is well documented and needs little repetition here. The relevancy of Kennan’s detailed analysis of the causes of Soviet behavior today is revealed, however, in a description of the repetitive character of Soviet governmental activity. The contemporary headlines about the trials of Soviet dissidents in 1973 rudely remind the observer that Russian leaders today, as in 1946, have yet to “make absolute the power which they seized in November 1917. . . .” Andrei Sakharov, described as a father of the Soviet hydrogen bomb, defied government orders to avoid contact with the Western press in the summer of 1973 by holding an interview for foreign correspondents in his home.4 This flagrant, premeditated act of disobedience itself was noteworthy, but his message to the West was more than thought provoking; it was alarming.

Sakharov warned that the further progress of détente between the United States and Russia without more freedom for Soviet citizens was a danger to the West. Such a détente, he said, would confront the world with a heavily armed, closed, and therefore dangerous society. This kind of internal dissent and public outburst is embarrassing; but when linked with similar warnings by Alexander Sohhenitsyn, world renowned novelist; economist Victor Krasin; Pyotr Yakir, son of a former general; and a dozen other prominent figures now in “mental institutions,” the danger to the control of the Communist Party is evident.5 Internal repression is again the result. Under these circumstances, the need for respite from the external pressure of the very powerful United States is all the more essential. Nevertheless, it must be noted that some external enemy still appears necessary to the Russian government; hence, the shrill anti-Chinese diatribes reach new heights of bitterness. The external enemy remains a necessity to explain away the continued maintenance of absolute dictatorial authority by the state at home.

Kennan’s observation that, while no “sincere community of aims” was possible with a capitalist state, the needs of Russia for economic assistance from the advanced capitalist countries could alter her public behavior certainly appeared to be an accurate analysis in the 1970s. American headlines in 1972–1973 ranged from the announcement that David Rockefeller and the Chase Manhattan Bank were opening an office in Moscow to that of the largest wheat trade deals in commercial history. In spite of the all too apparent deficiencies in the capitalist systems reflected in monetary crises and inflation, Soviet leaders had little ideological difficulty in changing the Soviet headlines from castigation of the imperialist warmonger to warmer descriptions of the U.S.-Soviet détente. Such reversals, apparent through the entire Soviet era, require the maintenance of the “principle of infallibility,” which continues to require the iron discipline of the Communist Party. Dissent is therefore considered not only anti-Communist, it is contrary to the continuation of the present Soviet state system.

Finally, and most critically, the successful implementation of United States policy to build the “unassailable barriers” to restrain or contain the expansive character of Soviet national power has been impressive. After more than a quarter of a century of successes, the implementation has been mistakenly impeded during the last six years by a bitter and divisive war on the Asian subcontinent. It is “mistakenly” impeded because it is, in fact, this Vietnam War, following the shaking experience of the missile crisis in Cuba in 1962, which in time will be described as the final and most successful chapter in the waging of the cold war by the free world under United States’ leadership.

The “cold war” was a struggle among the great powers, with Russia and the United States in particular as the primary adversaries, not for the minds of men, but for political and economic influence which would make one predominant over the other and, perhaps, to make one safe from the other. The ‘‘intelligent long-range policies” applied with patience and perseverance included the building of a worldwide system of barriers to Soviet expansionist policy. The Greek-Turkish aid act, the Marshall Plan, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the Berlin Blockade, the defense of Korea, the Southeast Asian Treaty Organization, the rehabilitation of Japan, the freeing of Austria, the defense of Israel and the Congo, the missile crisis, the modernization of Iran and Brazil, the resurgence of Indonesia, the defense of Vietnam, the pressure to end “the wars of national liberation” in Latin America and Africa comprise only a partial list of the extensive U.S. efforts to help states, nations, and areas to be free from the consequences of an uninhibited Soviet expansionist policy.

The inclusion of the last three items in this listing (Southeast Asian problems in general and “wars of national liberation’’ everywhere) has been the most difficult to comprehend in recent years. The inclusion of these items is critical, however, to a full understanding of the successes of the Kennan thesis, for these are the most important and the final pieces in the “cold war” puzzle.

A military contest between the United States and Russia (or China) need never have occurred in Southeast Asia. Certainly, the existence of any comprehensive U.S. policy for this area of the world in 1945–1946 would have prevented the French attempt to restore her empire in this theater. A Vietnam under the leadership of a Ho Chi Minh could have established at worst an Asian “Tito.” Following this policy failure, the United States could have insisted on elections in 1956, thus insuring some degree of stability and unity under Ho Chi Minh, as the late President Eisenhower believed would have been the case. Or, contrary to Eisenhower’s assumptions, the successful leadership of the late President Diem might well have been ratified at an internationally supervised election in the South. It is most doubtful that the North Vietnamese would ever have permitted such an externally supervised election in the North and they said as much; thus, a third alternative was possible, an internationally supported President Diem in South Vietnam quite similar to President Syngman Rhee in South Korea the previous decade. These policy failures were certainly deviations from the Kennan thesis which required policy constancy. With the advantage of hindsight, a number of scenarios can be written for this period, each suggesting that on the Asian subcontinent peace, not war, was at least a viable option. Opportunities were missed and mistakes were made in this early period.

After the breakdown of the Eisenhower-Khrushchev dialogue of 1959–1960, however, and the eruption of dangerous Russian cold war ventures in Cuba, Berlin, and the Congo in 1961–1962, a major change in the character of United States-Soviet interests in Southeast Asia appeared inevitable. In a period of apparent American policy vacillation, the Soviet leaders engaged in a new round of expansionist policy thrusts. Experimentation with a new type of guerrilla warfare in Latin America by Russia via Cuba rapidly became the newest and most dangerous manifestation of Soviet expansionist policy. This new experiment quickly spread across the third world with a new label: “wars of national liberation.” Indochina became the crucible for the full scale test, and the United States and Russia emerged as the principal antagonists again.

Former Secretary of State Dean Rusk, in an appearance before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on January 28, 1966, restated his understanding of the continuity of U.S. policy.6 He quoted President Truman’s March 1947 statement of the U.S. basic policy vis-à-vis the Soviet expansionist policy:

I believe that it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples7 who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures. . . . [the] central issue in the dispute between the two leading Communist powers today (1966) is to what extent it is effective—and prudent—to use force to promote the spread of Communism. If this bellicose doctrine of the Asian Communists (wars of national liberation) should reap a substantial reward, the outlook for peace would be grim indeed.

The Secretary advised the Senate that the United States was supporting the South Vietnamese as a part of “their right of individual and collective self-defense.” He recited the list of similar ventures, including the airlift to supply Berlin during the blockade and the aid to Greece, and said “nobody suggested that (those were) illegal, but were acts in pursuit of peace.” Rusk attempted to put the Indochina war question in a larger perspective by explaining a faulty peace start in late 1965. He explained that when a joint Russian-North Vietnamese statement was issued in Moscow about a proposed conference for peace in Laos and Cambodia, the United States immediately indicated a strong interest. Then, he said, “It was our information that Peking moved in . . . to block the prospect of such a conference . . .” The test of wills was never between the United States and North Vietnam as far as the U.S. policymaker was concerned, but with Russia and secondarily with China. The Kennan containment policy was still the foundation of U.S. policy vis-à-vis the Soviet Union.

The Indochina war has been examined in great detail but, as a rule, each of the studies was developed largely in isolation from the world scene. It was certainly the most unpopular war in modern U.S. history in its final years, though often for reasons the critics could not explain. Eugene Rostow notes, in his work Peace in the Balance, Richard Rovere’s conclusion that from the point of view of international politics and of American interests there is no significant difference between the (Russian-supported) attack on South Korea and the (Russian-supported) attack on South Vietnam. Rostow notes:

With memorable intellectual honesty, Mr. Rovere concludes his article by saying he was in favor of what we did in Korea and is against our course in Vietnam, but that he cannot explain why.8

Regardless of one’s view of the propriety, morality, or necessity of the Indochina war, its greatest significance to the author is not the price paid by the United States in men, material, or internal disruption, or the price paid by any of the participants. It is the important alteration in the behavior of the major powers as a result of the war. Regional, as well as nuclear conflict, appeared more remote in 1974 than at any time since the end of World War II. Further, it is concluded here that the termination of the Indochina war on any terms substantially different from those actually arrived at by the Nixon administration would not have permitted the development of the uniquely impressive new relationship among the great powers.

Peace in Vietnam was only possible when the Soviet Union, and to a lesser extent the People’s Republic of China, decided that the grand experiment with “wars of national liberation” was to be terminated, and the usefulness of such a policy in the future was minimal. Peace was possible because the Kennan thesis was followed here to its logical conclusion. The extent of the new great power relationship was made even more clear when Mao Tse-tung and Chou En-lai indicated in mid-1973 that they welcomed a continued U.S. military presence throughout the western Pacific from Tokyo to Bangkok. Even the leaders of the Soviet Union stand in awe and rage at this result of the “satisfactory” conclusion to the Vietnam War.

“Public memory in the United States is often short and quickly blurred,” wrote Henry Cabot Lodge in 1973 as he described how the war was finally ended.9 This public forgetfulness is well illustrated in the case of “wars of national liberation” which were being sponsored by Russia in Asia, Africa, and Latin America in the 1960s on a scale which seemed to be of epidemic proportions. By 1973, with the exception of minor anti-Portuguese guerrilla raids in Africa, the epidemic of these “wars of national liberation” suddenly ended without explanation or any formal pronouncement of a change in policy by their sponsors. It is reasonably certain that one would not hazard the suggestion that either the United States, or the underdeveloped states where these “wars” were occurring, had suddenly learned to deal with this threat effectively. In fact, the “wars” must have been called off as a matter of the highest policy for them to have ended so suddenly on a worldwide basis. A change in the policy of the Soviet Union was fundamental to an end to this phase of the cold war. The failure of this “liberation wars” thrust in East and Southeast Asia as it encountered the bloody barriers constructed by the Americans required this Soviet policy revision.

President Lyndon B. Johnson failed in his efforts to “smoke out” the Russians on the Vietnam War, even though he permitted Soviet ships and personnel in the war zone to become targets of U.S. airpower. Johnson, convinced that the “grand experiment” of the Soviets must be prevented from succeeding and certain that a negotiated settlement overseen by the Russians and Chinese was the only safe way to end that war, struggled to attain that goal of a negotiated settlement until he left office in 1969. His hopes for a negotiated settlement were left to be realized by his successor.

When Richard M. Nixon assumed the responsibility in January 1969, he, too, made clear that a negotiated settlement was the primary goal. By negotiations the U.S. government always meant an agreement acceptable to the great powers. Nixon, in a television address in November 1969, said, “We have declared that anything is negotiable, except the right of the people of South Vietnam to determine their own future” (e.g., “wars of national liberation”).10 This author’s appraisal is that the war critics never truly understood what the stakes in the war really were, and that today, in a sour mood reflecting neo-isolationism, they imperil the free world gains from the failure of that tragic Russian experiment.

To achieve a negotiated settlement, the Nixon Administration decided that it was absolutely essential to draw both the Soviet Union and China into the Vietnam War directly. This was done successfully by the decision to risk closing the ports of North Vietnam by mines on the eve of the U.S.-Russian summit meeting. In the waning hours of the war, it apparently was necessary to deliver one final warning to North Vietnam that the termination of this experiment with “liberation wars” would not be blocked. The virtually non-lethal mass bombing raids in December 1972 constituted that warning. The raids were condemned at home and abroad by critics, often well-intentioned persons who never understood the stakes in the struggle with or the goals of expansionist Soviet policy.

The Soviet Union and China, however, both cognizant of the peril of direct conflict with the United States, increasingly fearful of each other, and both in serious economic difficulty which the United States alone could help overcome, were fully aware of the issues. Further, they probably were prepared to close down the experiment well before their ally and proxy, North Vietnam.

The benefits of a satisfactory end to the Vietnam War are incalculable. “Satisfactory” certainly included President Nixon’s “peace with honor” with Russia and China’s continued public support for their fraternal ally, North Vietnam. In short, “satisfactory” meant that, while neither side achieved its immediate goal of victory, neither side lost any essential or definable goal and most importantly neither side lost “face.” The new great power relationship just was not realizable if either side had suffered defeat or the perception of defeat. The constructive results of the end to the Vietnam experiment include the Soviet and Chinese summit meetings with the United States, a reduction in the probability of great power conflict through further arms control negotiations, an understanding of the Middle East, and an array of proposed cultural, scientific, and economic arrangements.

The successful end to the war permitted the conversion of a two-power world into a multi-power world. Courtney Sheldon wrote in June, 1973, “Americans have played roles before in reorganizing the world and reestablishing peace after wars, great and small. But this is the first time that an American (Kissinger) in Washington has played a major role in reorganizing the whole structure of the world.”11 This new structure, however, is very fragile. It will require careful nurturing by all of the major powers to become strong.

The Soviet Union remains aware, not only of the significance of the idea of wars of national liberation, but of United States’ sensitiveness to the problem. In a thinly veiled warning to the United States, following a visit by Dr. Kissinger to Peking in February 1973, Vladimir L. Kudryatsev, Isvestia’s political observer, spoke on a series of radio programs about the issue. He spoke of the significance of the “Vietnam victory” and said that the Soviet Union would continue to sponsor revolutionary national liberation movements all over the world.12 The threat to revive the Vietnam experiment was a warning to Washington not to permit the U.S.-China negotiations to endanger the developing U.S.-Soviet arrangements for peaceful coexistence. Further evidence of the fragile character of the emerging great power relationships is seen in remarks by Premier Chou En-lai in September 1973. On the occasion of a visit of French President Pompidou to Peking, he denounced Soviet détente efforts in Western Europe. The Premier indicated his belief that Soviet successes at military détente with Europe may be paving the way for intensified Soviet pressures on China. The Vietnam War ended satisfactorily to permit the building of a new great power relationship. While all parties to these détente discussions are wary, each has indicated a believable intention to pursue a policy of peace.

Thus, the Vietnam War was indeed won! The people of the world now standing closer to true peace than at any time since 1945, perhaps in all modern history, are the victors. The price was an admittedly high one in human life, material goods, and disrupted families and societies. Yet, the price was a bearable one, if, as it now appears, the weapons for nuclear war are to be maintained solely for defense and the weapons systems for regional wars are to be more rigidly controlled by the great powers. The great powers apparently, and logically, have agreed that nuclear war for almost any reason would be suicidal, and that regional wars, in particular “wars of national liberation,” are counterproductive.

If one chooses to reject any part or all of this line of reasoning, however, the conclusions are still inescapable that the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China have arrived at a modus vivendi with the United States regarding war.

George Kennan was fundamentally correct in saying that Soviet expansionist policy could be contained only by the “vigilant application of counter-force at a series of constantly shifting geographical” locations. Any review of post–World War II United States activity will quickly illustrate the necessity for flexibility over a long span of years. Kennan’s prediction of a fifteen year struggle was short by a decade, perhaps only because the United States was at times too inflexible, but more probably because “adroitness” in policy application was a casualty in the final years of the Eisenhower administration. The cost of the cold war to the Soviet Union has been a terribly high one requiring that “iron discipline” which, as the technology of communication advanced, has become increasingly difficult to maintain. “Soviet economic deficiencies” have become more pronounced, not only making the state vulnerable in a world economic system, but requiring the new generation of Soviet leaders to compromise publicly and to accommodate with the despised capitalists.

The systemic seeds of state weakness described by Kennan were imaginatively exploited by the United States in a way that permitted a change in basic Soviet policy towards détente. The final piece in the puzzle was carefully set in place by the Nixon-Kissinger opening to China.13 This confronted the Soviet Union with an unacceptable political situation which, when joined with a deteriorating economic situation, logically required fundamental policy changes.

The great concern now is that the new and workable arrangements with the socialist states will be disturbed or undermined because the United States, torn by internal political strife, may not have the “spiritual vitality” and confident, supported presidential leadership necessary to complete the task about which Kennan wrote. As Kennan suggested, exhibitions of weakness, disunity and, in particular, a lack of national purpose, have an “exhilarating,’’ and therefore very dangerous effect on the Russians. Thus, the question in 1975, as in 1946, may be whether the United States can “measure up to its own best traditions” and provide the ‘‘moral and political leadership” without which the probability of failure is dramatically heightened.

Appeals to reason do not always meet with success when directed to competing partisan political leaders. Senators and congressmen in particular, who have a normally greater interest in domestic affairs and recognize that the conduct of foreign policy is largely an executive matter, can be especially obstructive in their approaches to foreign policy problems. The danger inherent in this executive-legislative relationship is that the frustrations of two undeclared wars in the last twenty years will lead the United States to repeat the errors of judgment now manifest to historians who write about the period between the two world wars. Eugene Rostow says, “it is hard to imagine our repeating (those) follies. . . . But we may. After all, we did so once before.”14

Neither the Soviet Union nor the People’s Republic of China has cut back on its defense efforts. In fact, the Russians have increased their expenditures in selected areas, all of which are included in offensive war capability. Chou En-lai at the Party Congress in August 1973 indicated the reasons why China must increase expenditures. He said that the Soviet Union and the United States “while hawking disarmament . . . are actually extending their armaments every day. Their purpose is to contend for world hegemony . . .” As an aside, for the benefit of the United States, he did add that “Sino-United States relations have been improved to some extent.” While peace is the ultimate goal, immediate fears for state security have certainly not been overcome.15 The U.S. Secretary of Defense, on the other hand, finds himself in a constant battle to prevent the emasculation of U.S. defense programs and to prevent a change in defense capability expenditures which is inconsistent with U.S. foreign policy goals. Adam Ulam warned in a recent work that:

Realism will demand a sober appreciation of . . . the Communist world . . . (to avoid) a strong temptation for both the government and public to exaggerate the extent of the Soviet Union’s moderation . . .16

Charles E. Bohlen in the concluding passages of Witness to History 1929–1969 expresses this danger in stronger language:

I do not think we can look forward to a tranquil world so long as the Soviet Union operates in its present form. The only hope, and this is a fairly thin one, is that at some point the Soviet Union will begin to act like a country instead of a cause.17

A collateral problem is that in the United States a political attitude that is unhealthy for the country has emerged from the scandal of election politics. At the same time an anti-war climate, shaped by disillusionment with an unpopular war and its inflationary consequences, is becoming increasingly pacifist and is ignoring the necessity of essential defense. The time when the “vigilance” about which George Kennan wrote in 1946 has not passed. If the Vietnam War is someday described in history books as the last military battle of the cold war, perhaps the last important war of the twentieth century, it will be because vigilance is maintained for years to come. Further it will require, as Kennan stated, that the United States make the con-commitant financial sacrifices under a vital leadership “which knows where it wants to go . . .” and can continue to cope “with the responsibilities of the World Power. . . . Thus the decision (peace or war) will really fall in large measure to this country . . .” in the 1970s and beyond, as it did twenty-five years ago.

In 1946, George Kennan, in an intellectually superior analysis came to these conclusions about a forthcoming era and set his country and the world on a path toward eventual peace. The essential correctness of his analysis is unchallenged.

The discouragement and disillusionment which have become increasingly prevalent in the United States are a product of the belatedly unpopular Vietnam War. The doubts and recriminations were premature, since the Vietnam War has proved to be substantial evidence that the original thesis was correct and continues to be the basis for sound U.S. policy in the 1970s. The Soviet Union found “unassailable barriers in its path” to its expansionist policy over the last quarter century. It has accepted them reasonably philosophically and now, once past the ultimate test in Vietnam, has finally chosen the path of accommodation. George Kennan was right and the Vietnam War is the most convincing evidence of the validity of his thesis.

The differences in observable opportunities in the 1970s for peace, as a result of the successful implementation of Kennan’s analysis, are monumental. Assuming that the United States remains militarily alert and able, the tools for great power competition in the last quarter of the twentieth century will be economic rather than military ones. Their successful employment will mean economic competition and cooperation as a truly world economy develops. Thus, the competition will be economic rather than military, and the gains or losses recorded on the national balance sheets will be financial rather than human.

Eric Weise is a professor emeritus of political science at the University of Cincinnati and authored an extensive newspaper series on U.S. policy in Asia.

- “X” (George F. Kennan), “The Sources of Soviet Behavior,” Foreign Affairs, July, 1947. ↩︎

- Kennan had been concerned about the Truman administration elaboration on his analysis from an early date. ↩︎

- George F. Kennan, Memoirs: 1925–1950 (Boston: Atlantic-Little Brown and Co., 1967), pp. 314–21, 357–67; excerpts in Jerald A. Combs, Nationalist, Realist, and Radical: Three Views of American Diplomacy (Evanston: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1972), pp. 447–64; “The Statement and Testimony of the Honorable George F. Kennan,” Vietnam Hearings (New York: Vintage, 1966) pp. 107–14, 129–33. ↩︎

- “Soviet Dissent on Trial,” Christian Science Monitor, September 1, 1973, pp. 1, 6. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 6. ↩︎

- Vietnam Hearings, pp. 3–5, 17–21. ↩︎

- A discussion of the phrase “free peoples” is not relevant here since it clearly included, as a matter of U.S. policy, those peoples or territories not then under the control or hegemony of the “Communist” states, and was certainly not a reference to the character of the relationship between the governors and the governed. ↩︎

- Eugene V. Rostow, Peace in the Balance (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972), pp. 190–91. ↩︎

- Henry Cabot Lodge, “How the Impossible Peace was Won,” Readers Digest, June, 1973, pp. 70–74. ↩︎

- Richard M. Nixon, Television address, November 3, 1969. ↩︎

- Joseph C. Harsch, “Summit 11: Keeping the Peace,” Christian Science Monitor, June 25, 1973, p. 1; Courtney R. Sheldon, “Summit 11: Kissinger Strength Aided U.S.,” Christian Science Monitor, June 26, 1973, p. 1. ↩︎

- Paul Wohl, “Kissinger’s China Visit Triggers Soviet Invective,” Christian Science Monitor, February 21, 1973, p. 5. ↩︎

- Alan M. Jones, “Nixon and the World,” in U.S. Foreign Policy in a Changing World, ed. Alan M. Jones (New York: David McKay & Company, 1973) pp. 27–44. ↩︎

- Rostow, Peace in the Balance, p. 340. ↩︎

- Dana Adams Schmidt, “New U.S. Pattern in Asia,” CSM, September 5, 1973. ↩︎

- Adam B. Ulam, The Rivals: America and Russia Since World War II (New York: Viking Press, 1971), pp. 389–90. ↩︎

- Charles E. Bohlen, Witness to History 1929–69 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1973). ↩︎