The modern must be contrasted with the ancient or the traditional, and so conservatives are characteristically skeptical if not contemptuous of every modern claim. Thinkers usually regarded as conservative, from Leo Strauss to Jacques Maritain, trace the beginning of modern thought to Niccolo Machiavelli. The Machiavellian innovation was to devote human beings to the conquest of nature, to turn human efforts toward the acquisition in freedom in this world of what God had promised in the next. Machiavelli redefined human virtue as whatever works in transforming the world in the name of human security. He reduced religion to a useful tool in achieving political goals. Machiavelli even deprived philosophy of its high and independent status of contemplating the truth about nature and God by holding that the truth is that we only know what we make. Every human claim for wisdom must be tested practically; we can only know the world by changing it.

Thus, moral and political life in modern times no longer aims to cultivate human souls but to protect human bodies. The attempt to use political means to elevate the soul turned out to be ineffective and needlessly cruel. We cannot make human beings good through an appeal to moral and religious motives, but we can make them act as if they were good by using fear to predictably control their bodies. So the modern premise is that human beings are free individuals with no duties given to them by God or nature; their only duty is to obey those contracts, ultimately based in fear, which they have made with other individuals.

Characteristically, modern government uses strong political institutions—such as the separation of powers and checks and balances—to limit and direct human action. The main goal is to protect human beings from the tyranny of unlimited government without expecting too much of either rulers or ruled. Modern government, in fact, is to be limited but strong; free human beings consent to be ruled in order for their bodies to be more secure and comfortable. But they would not consent to be needlessly afraid of government or to have their souls cruelly tortured. So the American Constitution, for example, creates a strong presidency that is limited both by Congress and by the necessity of securing reelection.

This moderate and modern form of government must be praised for its effectiveness, for its protection of human security and liberty, and for providing a context for unprecedented human prosperity. But conservatives would add that no decent modern government has been wholly modern. Decent modern governments have relied heavily on their premodern inheritances, including respect for tradition, religion, and various kinds of uncalculating virtue. Strong institutions are not enough for a free society to work; good government always depends also on the existence of free and responsible citizens, and these do not just happen. Modern society, conservatives add, erodes its premodern capital. It sows the seeds of its own destruction.

Conservatives have plenty of evidence that modern thought and action are not in the long run compatible with moderation. Modern, limited government gave way to revolutionary efforts to use unprecedented forms of cruelty to perfect human existence on this earth. Marxist thought might be viewed as a more consistent form of Machiavellianism. All means necessary might be used to bring heaven to earth, and terrible cruelty in the short term might be used to obliterate cruelty altogether over the long term. Without something like revolutionary success, the modern fear became, the modern world might be judged a failure. The moderns’ success in reducing the recognized presence of God in the world and in allowing people to acquire more wealth and power, argue conservatives, has made them more anxious and restless and on balance less happy.

That the deepest modern impulse is necessarily revolutionary might first have been noticed by Jean-Jacques Rousseau: The bourgeois individual that moderate modernity brought into being is miserable and contemptible; he has no idea what virtue and happiness are. But Rousseau still embraced the modern premise that there is no going back to the simple and noble world of the citizen and the saint. He concluded that modern efforts must be radicalized to eradicate human individuality altogether. The modern paradox is that a world that began with the celebration of the free and unencumbered individual seemed to culminate in the worst form of anti-individualistic or misanthropic tyranny. Modern thought created the bourgeois individual, and then it became radically antibourgeois.

The best student of Machiavelli of our time, Harvey Mansfield, has remarked that if Machiavelli were alive today he would admit he was wrong. The Florentine’s view was that Christianity was the cruelest form of domination over the human soul imaginable, but today he would know that it was nothing compared to the ideological tyranny of the twentieth century. That fact surely would have caused him to reevaluate premodern Christian virtue, says Mansfield, which offered the most steadfast foundation for dissident resistance to communism. What Machiavelli regarded as unnecessary classical and Christian constraints on human freedom are in fact largely based on the realistic premodern distinctions that separated beast, man, and God.

The modern project has been to turn human beings into gods, but the foundation of that effort has been the proposition that the human being is merely a body, just another animal. It is characteristically modern to be so devoted to freedom that the limitations and directions nature and God have given human beings seem like tyranny. It is equally modern to believe that anyone who thinks that human beings have souls—are more than bodies—has fallen victim to tyrannical delusion. As Blaise Pascal predicted near the beginning of modernity, the result of that confusion has been more to brutalize than to divinize human beings.

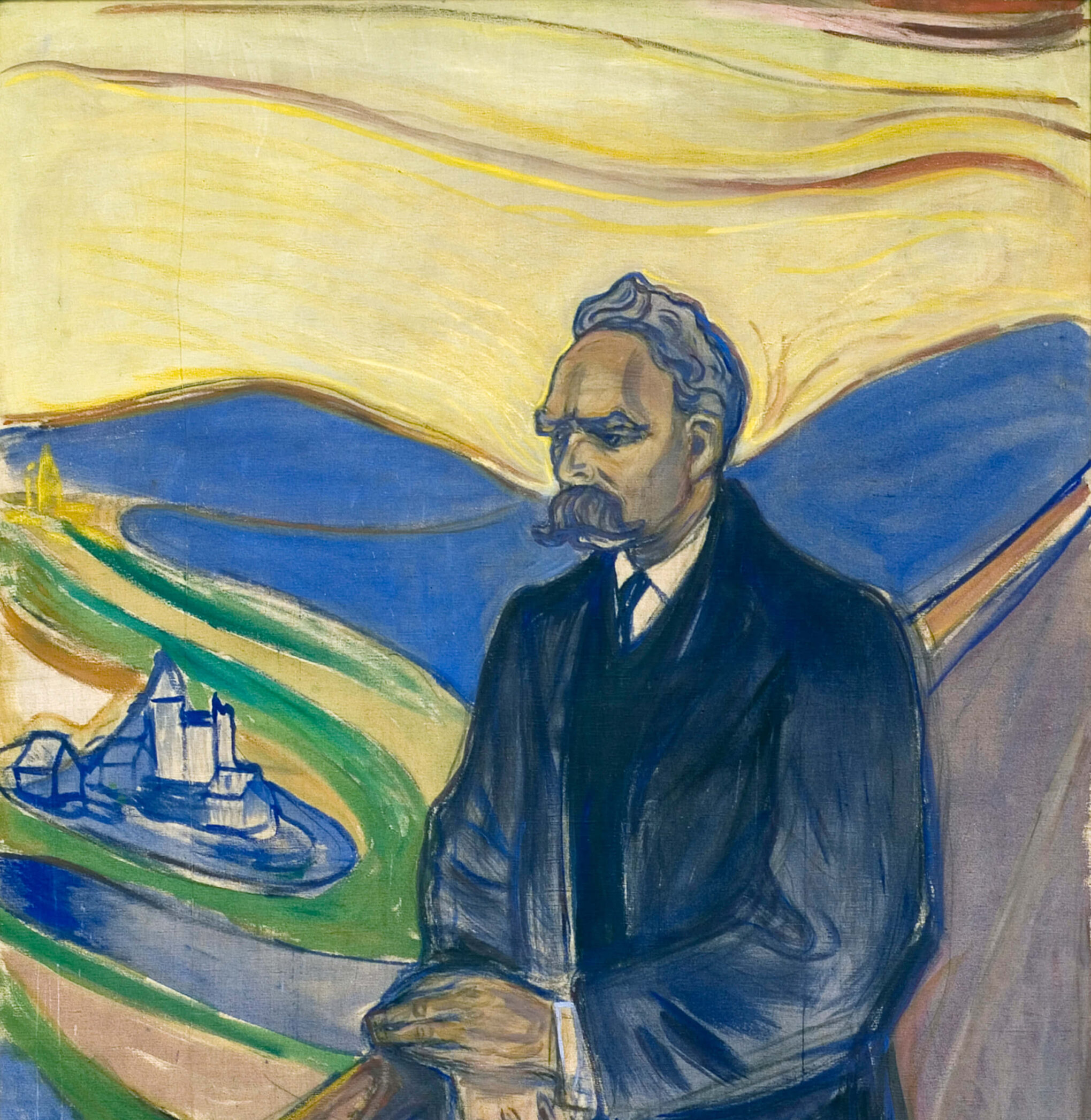

Another view of the modern paradox is the Hegelian/Marxian claim that the aim of the modern world is to bring history to an end. Modern thought understands the human being as free from natural determination to create himself or make history. So the end of history would have to be the end of human liberty. The end of our free or godlike striving is to make ourselves merely animals again. Rebellion against this conclusion is the beginning of postmodern thought. Most postmodern thought follows Friedrich Nietzsche in an effort to liberate human will or greatness from the reductionistic tendency of modern scientific reason. Postmodernity so understood is the celebration of free human creation for no particular purpose. History cannot end because history can have no real point; anything rational or predictable is inhuman.

But this alleged postmodernism is, in truth, an intensification of the modern tendency to liberate human will from natural and divine constraints. The modern project is in effect criticized by the postmoderns for not being modern enough, for having a residual faith in the goodness of human efforts and in the possibility of human progress. The postmodern view is that the modern project is even crueler than Christianity because it ruthlessly and futilely aims to impose scientific order or direction on chaotic human reality. Thus, most postmodern thinkers, on rather Machiavellian premises, reject modern science and replace it with the human imagination. Only the imagination can give human beings the experiences of security and comfort they crave. We can use the imagination to control our experiences, even if we cannot really eradicate human contingency and mortality.

Postmodernism as it has evolved would have repulsed Nietzsche, who connected great or authentically human willing with the reality of the human experience of the “abyss,” of the nothingness that surrounds our brief and accidental existence. The greatest of postmodern thinkers—Martin Heidegger—renounced resolute Nietzschean willing after his ineffective performance as a Nazi. But the murky later thought of Heidegger seems too much like fatalism to be very inspirational.

There is also a less noticed conservative postmodernism—postmodernism rightly understood. This authentic postmodernism is based on a criticism of modernity for its lack of realism, for its inability to tell the truth about the greatness and misery of being human. The basic human experiences are of limitation and of responsibility; to live well, human beings must accept the distinctively human duties that come with living in light of the truth. The bad news is that human beings are not free to impose their own will on nature; they cannot make and remake the world to suit their convenience. The good news is that they are fitted by nature to know the truth they did not make and to be open to God. They were born to know and love, not just to suffer and die. This sort of postmodern thought is associated with Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and American literary Thomists such as Marion Montgomery, Walker Percy, and Flannery O’Connor.

Conservative postmodernism does not entail the wholesale rejection of all that the modern project accomplished. The achievements of modern science and technology, for better and worse, will remain with us, and the postmodern task is to subordinate them to properly human purposes. The genuine successes of the best modern forms of constitutional government deserve to be perpetuated, but the liberty they protect has to be understood as the liberty of human beings, not beasts or gods. Human liberty must be freed from any confusion with either liberationism or libertarianism. Postmodernism is in many ways a revolution in thought, but it is not intended to produce revolutions in practice. Perhaps the shortcoming of late modern political thought is the completely unsubstantiated belief that political revolutions could ever be relied upon to cure what ails human beings.

Further Reading

Romano Guardini, The End of the Modern World

Peter Augustine Lawler, Postmodernism Rightly Understood: The Return to Realism in American Thought

Mark Lilla, The Reckless Mind: Intellectuals in Politics

Darrin M. McMahon, Enemies of the Enlightenment: The French Counter-Enlightenment and the Making of Modernity

Daniel J. Mahoney, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn: The Ascent from Ideology

Leo Strauss, Natural Right and History

This entry was originally published in American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia, p. 580.