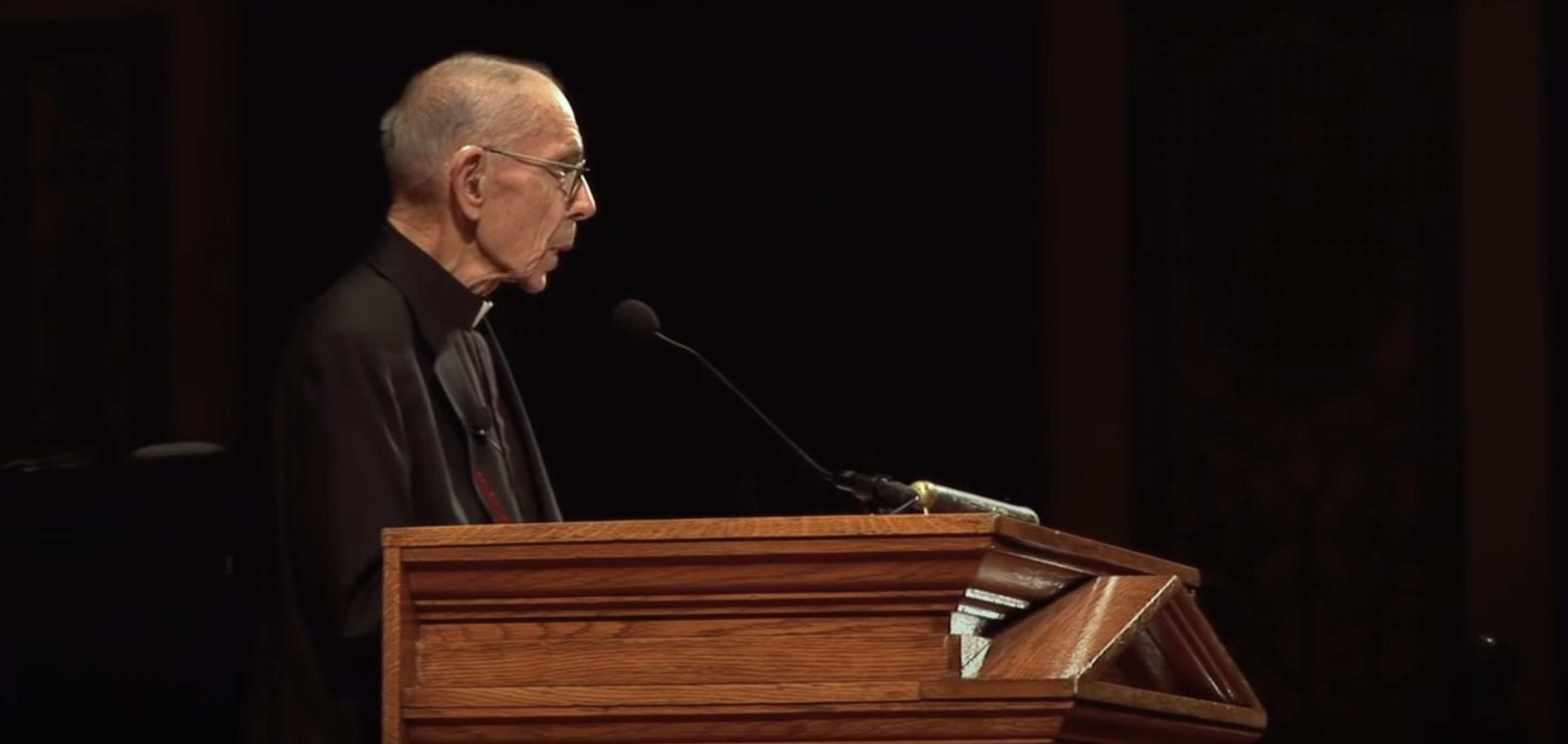

Father James V. Schall, S. J. remains a beloved figure among those who value intellectual curiosity, liberal learning, whimsical writing, and fidelity to the best of classical and Christian wisdom. He was a kind and witty man who corresponded widely with friends and admirers (myself included) right up to his death at the age of ninety-one on April 17, 2019.

His private letters and emails were always a pleasure to receive, not least because of the infectious humor and affection that informed them. His public readers delighted in his reading lists, his enthusiasm for the wisdom to be discerned in books old and new, his joyful assent to reality, and his determined resistance to every form of utopian delusion and ideological substitute for “the truth about man.”

His learning was so broad—so eminently reasonable, so grounded in reality—that it is easy to overlook the depth of insight, the considered wisdom, that informs his intellectual corpus as a whole. With the publication of The Nature of Political Philosophy: And Other Studies and Commentaries, edited by the Jesuit political theorist William McCormick and published by Catholic University of America Press last December, we now have access to Schall’s achievement in a truly synoptic way.

This new collection of Schall’s work, outlined and prepared for publication by the author himself before his death, includes fourteen learned essays and four commentaries that are at once scholarly and accessible. The book aims to explore the relationship between political philosophy, philosophy and metaphysics, and revealed truth in a way that does justice to them all—in their relative autonomy and necessary complementarity, interpenetration, and hierarchy.

All the Schallian themes are here, but expressed and explored with unusual clarity and penetration. This is ultimately a philosophical book that aims to illumine the nature of political philosophy and its place in the scientiae humanae. In it, we hear Schall’s distinctive voice and learn about his enduring concerns.

As Father McCormick points out in his editor’s preface, Schall’s thinking reflected his confidence in the ultimate harmony of faith and reason. Schall was acutely aware of the myriad modern pathologies that haunted the proper understanding and exercise of both faith and reason. Diagnosing these pathologies was one of his specialties. As McCormick astutely remarks: “If Father Schall was not always impressed by the deliverances of modern political thinkers, it was because he viewed them as rejecting the classical tradition as much as they rejected Christianity.”

***

The substantial 2016 “Autobiographical Memoir” that prefaces these essays and commentaries is the closest thing we have to an authorial précis of Schall’s abiding intellectual concerns. Looking back on a very long life and nearly sixty years of philosophical reflection, the Jesuit political philosopher was struck by the fact that he had published forty-five books, which usually had a series of artful and leisurely essays at their foundation. He cherished the essay, where he was able to express his “delight that things are is not something I impose on reality, but something that reality excites in me.” Schall found joy in the receptivity of the human mind to the givenness of things, to a “created natural order” that allows human beings to experience its sheer abundance and gratuitousness.

In this vein, in books like Idylls & Rambles: Lighter Christian Essays and The Classical Moment: Selected Essays on Knowledge and Its Pleasures, Schall allowed a playful “lightsomeness,” as he calls it, to come to the fore. Schall never begins with complaints, with theodicy and the problem of human suffering, or even with reflection on human imperfection (a reality about which this stout anti-utopian thinker was fully aware). Joy and gratitude to God and the larger “order of things” at the heart of his Creation always took priority for Schall. They put everything else in perspective. This explains in part his admiration for, and affinity with, G. K. Chesterton, about whom he wrote widely. (See his charming book Schall on Chesterton: Timely Essays on Timeless Paradoxes.)

Having grown up in Iowa, Schall does lament a certain lack of intellectual sophistication in his youthful formation. He dryly remarks that there were no “lycées” or “gymnasia” in the Midwest of those days. He was therefore a self-described “late starter.” In his training with the Society of Jesus, he was introduced to Aristotle and Aquinas, who would become lifelong companions and interlocutors. A series of eminent teachers, including Charles N. R. McCoy and Heinrich Rommen, allowed him to study political philosophy in the light of the fullness of the Great Tradition and the experience of modern totalitarianism. By his early thirties, he was reflecting on the significance of the deaths of Socrates and Christ for the nexus of concerns tying together philosophy, political philosophy, and revelation. This nexus would remain a preeminent theme.

***

In Schall’s view, justice and friendship were essential to the prospects for human happiness, excellence, and flourishing—to a well-ordered soul. But they were theoretically and practically incomplete, and even unsatisfying, within a strictly natural horizon. Human beings keenly desired permanence in their loves and friendships. Yet even the city, which purported to transcend individuals, was destined to pass away. Schall thus began to appreciate that revelation could address questions and satisfy aspirations that arose naturally in civic and human life but that were left unsatisfied on a merely natural plane. Schall also learned from the classics (and this insight deepened over the years) that an inordinate desire to achieve justice, that is, perfect justice, could lead to hell on earth, giving rise in modern circumstances to allegedly “scientific” or ideological projects to eradicate evil from the face of the earth.

In “On the Scientific Eradication of Evil,” an essay in The Politics of Heaven and Hell (re-released by Ignatius Press in 2020), Schall brilliantly restates the classical Christian attitude toward evil in the world. The possibility of evil is coextensive with human freedom and with the fallen character of human beings. But a world where evil is mixed with good should not be seen as a calamity, a reason for despair. Evil can give rise to good through patience, humble suffering, repentance, and the quest for redemption.

Schall was profoundly appreciative of the fact that out of the worst regimes, the most implacable tyrannies, men and women of integrity had arisen who refused to yield to violence and lies. He admired Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn for this very reason. Schall therefore adamantly opposed the idea so central to late modernity and progressive Christianity that evil stems not from the darkness in the human heart, as Jesus states with great forcefulness in Mark 7:14–23, but rather from unjust “social structures.” This is the view of Rousseau and Marx, not Jesus Christ or St. Paul. In Schall’s view, ideological projects that aim to eradicate the sources of evil in the world magnify evil in unimaginable ways.

Christianity, in contrast, “defined, identified, and rejected evil in any of its willed forms.” But the Christian religion has always been “instinctively uncomfortable with grandiose theoretical schemes to eliminate” evil from the world. True Christianity is above all attentive to “the movements of grace and desire” in each person’s heart and soul. Schall reminded his readers of these elemental truths. He also taught that in modernity the worst regimes are almost always tied to a perverse “substitute metaphysics” that in one way or another denies the created order. Ideological movements in particular took the “modern project” (Leo Strauss’s phrase, freely adopted by Schall) to extreme limits by sacrificing “freedom, creativity, grace, even life itself” for some “ultimate happiness” that “is not to be found in this life.” It pained Father Schall that progressivist and liberationist circles within the Church had bought into the illusion, prompted by the Father of Lies, that wickedness could be expunged from this world by human hands and without God’s grace.

***

In the progressivist deformation of Christianity, the four “last things” of the Christian tradition—death, heaven, hell, and purgatory—were replaced by a radical project of this-worldly transformation. Following the anti-totalitarian political philosopher Eric Voegelin as well as Pope Benedict XVI, Father Schall saw the “immanentization” of Christian hope as a political project rooted in a “deviant metaphysics,” a sure invitation to tyranny and terror. Friendship and justice are indeed precious goods, boons to the human soul and commodious living. But they do not reach their culmination in this world on the presupposition that men are gods and that the “natural order of things” can be changed at will. Schall warns us to be wary of any political order where men are obliged to call themselves “brothers” and “comrades.” Coerced brotherhood is no brotherhood at all. Aristotle in his Politics and Plato in his Republic had already taught this crucial lesson.

Schall also learned from Aristotle that the civic common good rests more on real friendship than justice, more on self-restraint than pushing one’s claims to justice, necessarily partial, to their logical conclusions. He states the matter bluntly: “Justice relations are harsh.” Friendship, in contrast, softens the indignation and anger that often accompany demands for justice, allowing room for a measure of civic comity and self-restraint by individuals and groups alike. Schall suspects this is the reason Aristotle dedicated two books of his Ethics to the topic of friendship in its various manifestations and only one to justice. And today’s social justice warriors too often forget that there is something higher than civic life, a contemplative order that puts our “activism” in a certain needed perspective. Nor is reckless activism the same as attentiveness to the civic common good.

Political philosophy thus has a complex practical task. It must educate the prudent politician in such a way that he will never be tempted to kill Socrates or Christ. That is for the sake of the city as much as to protect philosophy and religion for pursuing their noble and humanly necessary tasks. Politics must never think that it is higher than philosophical thought or religion, the goods of the free human soul. Conversely, the prudent statesman must “explain to the philosopher that there are ideas and habits among the philosophers that are truly disruptive of any good life among the citizens.” Here Schall appropriates an important Straussian theme. Finally, political philosophy must defend the “healthy degree of good sense” that is generally “found among normal citizens.” In that sense, Schall insists, “good politics usually depends on good philosophy” keeping bad philosophy (i.e., ideology) at bay.

There is a crucial “Augustinian moment” in Schall’s political/philosophical reflection. With Augustine, he held that one should not expect too much in this imperfect world, certainly not a cessation of suffering and strife or some eschatological fulfillment. Augustine was a quintessential political realist. Conversely, though, Schall expressed a profound appreciation of the “personal transcendent destiny” of human beings. Schall’s complex political philosophizing, informed by classical wisdom, St. Augustine, and St. Thomas, allowed him to honor “political life as the natural end of man while he is in this world.” Yet while intrinsically choice-worthy, politics “is not everything.” “The mind that is Catholic,” as Schall liked to put it, appreciates that “revelation is a knowledge that points to the limits of both politics and philosophy.” At the same time, “it confirms the validity of each in its own order.” There is an admirable equanimity and balance to Father Schall’s estimation of political philosophy in its relation to revealed truth and politics proper.

***

In The Nature of Political Philosophy, Father Schall eloquently defends “what is,” the natural order of things, against every form of “voluntarism,” of human will unbeholden to natural or divine limits. Schall is particularly sensitive to the way “will” replaces “nature” in the self-understanding of the modern project, the self-conscious philosophical enterprise informing the Enlightenment. Like Strauss, Schall sees Machiavelli as the modern par excellence, the subverter of a prudence subordinate to higher goods and truths. In The Prince, the Florentine emancipated the political art from the superintendence of the Good. The emancipation of the will is in turn a precondition for the conquest of nature, which culminated in various ideological attempts to conquer human nature itself. Schall knew that human nature can be wounded, assaulted, undermined, and left half dead by tyrants and ideologues who war with it. But can it be “conquered”? About that Schall was less sure, as the natural order of things had an integrity all its own.

Schall draws provocative parallels between modern philosophical voluntarism and a radical voluntarism evident in Islam’s self-understanding. When the will of the Prince or the will of Allah “deny the stable nature of any existing thing,” the human world is opened to forms of coercion bereft of moral conscience, of any sense of humanizing limits. Schall therefore saw Pope Benedict XVI’s much-maligned September 12, 2006, Regensburg Lecture (about which he wrote widely) as a wise effort to challenge both modern secularism and an Islam committed to the excessive voluntarism of the Qur’an. Such voluntarism fails to do justice to the role of reason and restraint at the heart of true religion and true politics. The God of Scripture is in no way the apotheosis of the human will, a vengeful tyrant in the skies. He is at once our Father and Friend, the antithesis of an all-too-human cosmic tyrant.

The modern project in its most radical philosophical articulations, however, wishes to free human beings from all natural and divine superintendence. That ill-advised emancipation gives earthly tyrants an open field to impose their wills on the raw material that is the human members of the body politic. Islamic voluntarism recreates the problem on a different plane. If Allah himself is pure will, then the very idea of a self-limiting natural order becomes impossible.

Schall says none of this to condemn individual Muslims, many of whom should be lauded for their piety and righteousness. The majority of Muslims are no doubt men of goodwill. But to insist that Islam is by its nature a “religion of peace,” as almost every secular and religious leader does today, and to treat Islamic voluntarism as an “accident,” a “contingency,” is at odds with the self-understanding of Islam itself. It does little or nothing to aid the cause of self-knowledge, moderation, and reform within Islam itself.

Father Schall exposes the voluntaristic roots of the modern project because he cares profoundly about the liberty and dignity of the embodied souls and spirits that we are. There is, he suggests, less reason and less “nature” (at least in any purposive or directive sense) in Enlightenment thinking than we often acknowledge. Bereft of both, radical modernity, “modernity without restraint” as Eric Voegelin called it, leads down a path beyond freedom and dignity. In speaking of “modernity,” Schall sometimes paints with excessively broad strokes, and he certainly does not write to undermine aspirations to moderation within philosophical modernity. But those aspirations almost always depend on dialectical openness to the premodern traditions of the West.

The Nature of Political Philosophy also makes clear that Schall remained skeptical to the very end about the Church’s increasing tendency to baptize the growing catalogue of “rights” to which late modern men feel entitled. Such rights too often coexist with “collectivism” or authoritarianism, the state enforcing new and spurious rights and thus coercively undermining authoritative norms and humanizing traditions. In making his case, Schall drew on the work of the theologian and political philosopher Father Ernest Fortin, a Catholic student of Leo Strauss who brilliantly documented how the modern tradition of Catholic social thought increasingly accepted ideological assumptions tied to “human rights” that were incompatible with the Catholic faith, right reason, and the natural law.

Did rights really have ontological priority over the duties and obligations that must necessarily accompany and inform them? Are some soi-disant rights simply a means of fleeing from the most elementary civic, moral, and religious obligations? Building on Fortin’s work, Schall noted that most Catholics, including numerous theologians, clerics, and even the most recent pope, failed to separate rights from the “pejorative meanings” with which they have become associated. Prominent Catholic politicians today openly stigmatize opposition to abortion, same-sex marriage, gender ideology, and the ideological cause du jour. Increasingly, transgressive rights rule the public order, and the Church finds it difficult to explain its opposition to them.

***

Schall liked to quote Voegelin’s wise remark that “No one is obliged to participate in the spiritual crisis of a society.” Father Schall found powerful resources to renew classical Christian wisdom in the writings of Pope Benedict XVI and Solzhenitsyn, who learned the truth of human nature in the Soviet gulag. The debt to Benedict and Solzhenitsyn becomes particularly apparent in Schall’s lovely little book A Line Through the Human Heart: On Sinning and Being Forgiven, published in 2016. In that work, Schall recovers the indispensability of repentance, and an accompanying sense of sin, to mercy and forgiveness rightly understood. When caritas is reduced to natural compassion and emotivist fellow-feeling, when sin is blamed nearly exclusively on “unjust social structures,” there is a denial, implicit or explicit, of the basic distinction between good and evil and the need of fallen man for divine sustenance and grace. Christianity becomes little more than a call for social activism at the service of eliminating the social sources of injustice. The Holy Spirit becomes “the spirit of what is happening now,” and progressive Christians unthinkingly “kneel before the world,” in Jacques Maritain’s apt formulation.

Or, worse, Christians succumb to ideologies that replace Christian hope with a “faith in progress,” as Pope Benedict XVI put it in Spe salvi. That luminous encyclical took aim at the ideological deformation of reality in the name of the theological virtue of hope. As Benedict said elsewhere, modern godless ideologies promised to “create a new, just, correct, fraternal world. Instead, they destroyed the world.” As the Marxists used to say, this was “no accident.”

What is forgotten is what Schall, following the famous words of The Gulag Archipelago, calls “the line between good and evil [that] passes through every human heart.” It is “this human heart” that is “the proper locus for forgiveness and repentance.” Without an acute sense of personal responsibility, without repentance at the service of truth, Christianity gives way to a “humanitarian” counterfeit. Without repentance, there is no proper reordering of the soul or genuine receptivity to the saving grace of God.

In the closing chapter of A Line Through the Human Heart (“Fifteen Lies at the Basis of Our Culture”), Schall suggests that for those shaped by “universal principles of reason and revelation” current Western culture, including American culture, is patently “based on lies.” These lies are legion and often camouflage themselves as new rights and privileges. For Schall, it is an obvious lie to say that abortion does not “kill a specific, actual human being,” however small and vulnerable. That is hardly a legitimate choice for morally self-aware human beings. It is a lie to say that marriage has no natural foundation in the “permanent, legal bond of one man and one woman who together form one flesh, inhabiting a home in which they beget and raise their own children.” It is a lie to say that war is “always immoral and never has any legitimate justification.” (As Leo Strauss once said of Socrates, Schall was not a pacifist precisely because he loved peace and loathed soul-destroying tyranny.)

It is a lie to say that the poor are poor because the rich are not; that is to justify class struggle, envy, and resentment in the name of “social justice.” It is a lie to claim that human beings uniquely threaten the survival of the earth, as if human “dominion” (tied to stewardship) has no legitimate place in the natural order.

Going back to his 1971 book Human Dignity & Human Numbers, Schall saw an undue pessimism and a not-so-covert nihilism underlying the more radical forms of environmentalism. He saw that its premises would inevitably justify collectivist coercion and demands for draconian population control. As a result, Schall did not hesitate to call out “green totalitarianism” as a specter haunting a West that had lost its sense of purpose.

The claim that there are no fundamental truths about man is perhaps the lie par excellence that gives rise to all the rest. It is a lie that “rights,” ever expanding and increasingly enforced by heavy-handed government decrees, exhaust what we know about human beings and how they ought to live together. It reflects a diminished philosophical anthropology and an impoverished political philosophy. To appeal to spurious psychological and sociological (and, we could add, racial, gender, and cultural) categories of an impersonal and deterministic kind in order to explain away evil and sin is to propagate a lie of the first order. Religious believers should never succumb to such reductionism.

And it is a lie of cosmic significance to deny that human beings are under judgment, not from a vengeful deity but from a God who respects human freedom and whose graciousness always informs His merciful judgment. Even the unbeliever should acknowledge something sacred and transcendent above the human will. “We did not make or establish ourselves,” Schall writes. He argues that this is an empirical truth independent of revelation—a foundational truth available through both reason and experience.

Father James V. Schall was a determined foe of every ideological effort to undermine the precious freedom and dignity of human beings, who are finally called to natural and supernatural felicity. Rooted in what one used to call the perennial philosophy (he sometimes called it “Roman Catholic political philosophy”), Schall’s political philosophy affirms and articulates the joy inherent in a free response to a moral universe and a spiritual cosmos that is purposive to its very core. In a brilliant essay in The Nature of Political Philosophy entitled “Political Philosophy and Bioethics,” Schall concludes by stating that human persons are “better made from nature,” in the capacious classical Christian meaning of that term, “than from anything [we] might propose as an alternative.” Realism, joy, and hope stand or fall together. Accepting benevolent limits saves us as individuals and polities.

Such is the wisdom of Father Schall: a humane realist, hopeful but never utopian. A great friend, priest, philosopher, and human being, his luminous writings will continue to shine a joyful light on “the order of things.”

Daniel J. Mahoney is a senior fellow at the Claremont Institute and professor emeritus at Assumption University. His most recent books are The Statesman as Thinker: Portraits of Greatness, Courage, and Moderation and Recovering Politics, Civilization, and the Soul: Essays on Pierre Manent and Roger Scruton.