At a recent meeting of the Philadelphia Society at the Saturday luncheon a prayer-person graced the meal with her benediction. After sundry reminders of our prosperity and well-being she got down to the nitty-gritty of the prayer, which was thanksgiving to God for His bestowal of market economics on a long-suffering world. Poor old God gets blamed for everything!

One might dismiss this bit of theological-economic hyperbole as an overly enthusiastic effusion induced by the excitement of the occasion were it not symptomatic of a deeper dislocation of religious thinking. God did not invent economic systems, just as He has not invented political systems and cultural forms. These systems and forms are of human making and devising. They are more or less satisfactory and are always conditioned by man’s inadequacy and sinfulness. To elevate a human invention, even though it mirrors inadequately and unsatisfactorily God’s order, is to worship man rather than God.

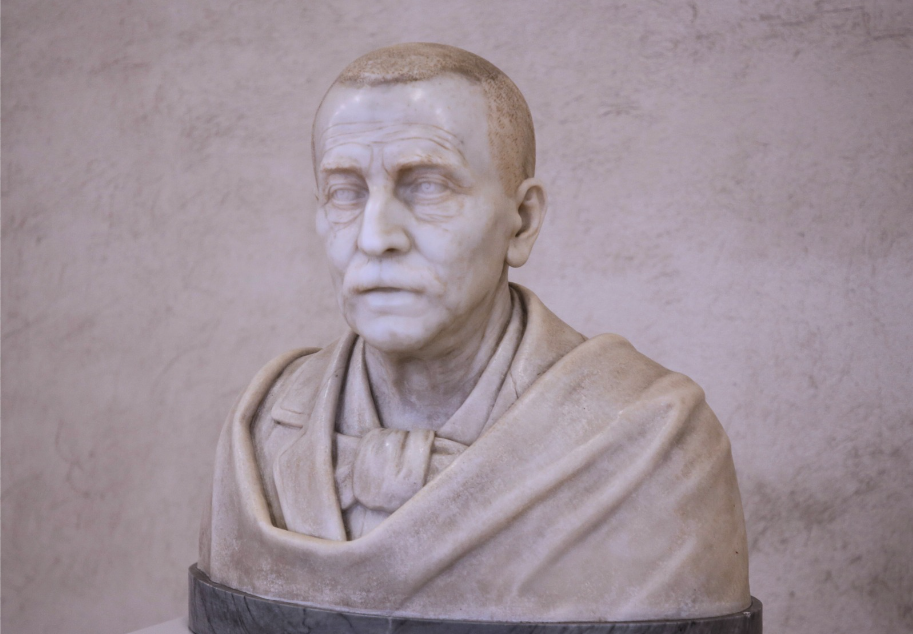

Karl Barth called such excesses of enthusiasm “idolatry.” Although Barth was a socialist, he was very careful to distinguish his socialism from the “will of God.” It seemed to Barth that socialism was the best social, political, and economic form that sinful man could manage. Today the ragged coat of last year’s socialism seems very far indeed from God’s will and very close to what sinful man would devise under certain circumstances.

There is, of course, an important lesson in this for contemporary conservatism. We have come increasingly to identify conservatism with the will of God and to give its forms and opinions a religious emphasis. Revelation and Christian tradition have not spoken on the legitimate and illegitimate forms of politics and culture. Indeed there are few men who, like William George Ward, wish a Papal allocution every morning with the Times of London to enable one to make a proper political judgment. That would be dyspeptic.

The Constantinian-Eusebian heresy which made the Emperor the head of the Christian Church and tied religion indissolubly to politics was, until the Reformation, believed to be incompatible with orthodox ecclesiology. Then Luther, Calvin, and Henry VIII confused constitutional forms with the sources of religious orthodoxy. This confusion was finally annulled by the American Revolution and the Second Vatican Council.

Is there then no relationship between religion and conservatism? One must approach this question with some diffidence. It is obvious that major “conservative” thinkers and political activists have been agnostics and atheists, or if nominally religious, saw their religious conformity as an expedient pragmatism. Even the religion of Edmund Burke is clouded with uncertainties. Burckhardt, Santayana, and, yes, if we are to allow that David Hume and Henry Adams were conservatives, all bore the weight of atheism. No one would dare to propose a litmus test for religiosity for membership in the Philadelphia Society. If being Jewish does not necessarily imply belief in the God of the Old Testament, being conservative need not imply an active religious faith.

Being “conservative” means the acceptance of certain postulates and insights into the nature of reality and human behavior. Being “conservative” implies, moreover, historical consciousness, a sense of tradition, family, and community. Not all conservatives are religious, but orthodox religious commitment is apt to imply a conservative political and cultural posture.

Being conservative is a quest for order in the realms of human experience. This order is not a humanly created order, invented as a form of political and cultural wish-fulfillment, but a discovery, through experience and history, that such is the way things are. The notion that man can create his own order, fashion his own paradise, build a universal utopian society, has been the human calamity of the past two centuries.

This underlying order which is perceived in the course of human experience and history never reveals itself in its completeness and perfection. Human limitations, passions, and sinfulness always stand in the way of a complete vision and harmonious accommodation. It is for this reason that the dream of perfection is the mark of a deranged political system. As James Madison wrote in one of the greatest passages in all political literature (Federalist #50),

. . . It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.

It is this insight into the power of unreason, sin, and passion in human affairs which lies at the heart of orthodox religiosity and conservative politics. Lord Acton’s dictum that we should always look for the “cloven hoof” in human affairs is the essential conservative premise.

The danger in the position of atheist and agnostic conservatives is that they may come to view their “rage for order” either as a sterile replication of the past without intrinsic meaning or an order arbitrarily created to fill the empty void of meaninglessness. The benign but empty conservatism of Burckhardt was but one teetering step away from the nihilism of Nietzsche, a secret which Burckhardt kept and Nietzsche recognized.

Finally, service in the cause of the good, the true, and the beautiful is always an act of compelling love. It can never be simply an empty rational gesture. That loving dedication to family, community, and all those who lent their lives in the past to the fashioning of living tradition can only be religious: “Love divine, all loves excelling.”

Stephen Tonsor was an author and a professor of history at the University of Michigan.