Whither the conservative movement? This debate has raged nonstop at least since 2015, when Donald Trump arrived on the scene. Samuel Gregg and F. H. Buckley, both veterans in the world of law and policy, have made significant contributions to the conversation, with around ten books and hundreds of articles published between them in the past decade. Gregg, who represents the classical-liberal or fusionist right, spent more than two decades at the Acton Institute before recently moving to the American Institute for Economic Research and has written numerous works on natural law and the ethics of the commercial society. Buckley, a self-described “progressive conservative,” is a professor at George Mason University’s Scalia Law School and was a speechwriter for Trump’s first presidential campaign; he has authored books on the rise of working-class politics in the Republican Party and the centrifugal forces that could lead to political secession in America.

Both scholars have written calls to action with different emphases but some areas of overlap. Gregg’s book The Next American Economy urges a recommitment to free, competitive markets in the face of prescriptions for protectionism and industrial policy. Buckley’s Progressive Conservatism presents a comprehensive policy agenda calculated to win national elections for the foreseeable future.

Gregg argues in his introduction that the United States faces two plausible alternatives. The first is “state capitalism,” which Gregg defines in this context as “an economy in which the government . . . engages in extensive interventions into the economy from the top down.” The attraction of such a system is its promise of security, both for vulnerable groups domestically and for the country as a whole in foreign affairs. Gregg prefers the second alternative: a free-market economy that positions America as a “modern commercial republic.” In this system, “bottom-up entrepreneurial drives” and open competition characterize the economy, and state power is strictly limited by commitments to property rights and the rule of law. Additionally, the citizens of a commercial republic “consciously embrace the specific habits and disciplines needed to sustain such a republic,” holding to the conviction that dynamic commerce helps advance “important virtues and civilization more generally.”

The remainder of the book examines these alternatives in greater detail. The three chapters of part 1 lay out the case against state capitalism. Chapters 2 and 3 argue that neither protectionism nor industrial policy delivers on its promises. Protectionism always has its defenders among the market sectors that stand to receive the protective advantage of high tariffs. Yet Gregg maintains that the logical arguments on its behalf are as flawed as they were in the eighteenth century, and empirical evidence indicates that protectionist policies undermine a nation’s long-term competitiveness and prosperity. Most of the decline in manufacturing employment over the past generation has been due to technological progress, not foreign competition. In fact, American manufacturing produces more now than ever before. When seeking to lay blame for the increase in social pathologies in regions like the Rust Belt, Gregg suggests that the sexual revolution, not Chinese factories, is the more likely culprit. On a granular level, Gregg cites research indicating that throughout U.S. history tariffs have been the result not of disinterested concern for the common good but of self-interested lobbying efforts by specific industries seeking protection from foreign competition.

Gregg defines industrial policy as policy that focuses on top-down steering of investment toward sectors deemed to advance national economic goals. This definition serves to separate overall economic policy from defense policy, where Gregg is much more comfortable with state intervention and guidance. Industrial policy, by contrast, suffers from crippling defects, in Gregg’s view. Its architects lack the knowledge necessary to match policies with their likely outcomes, and it is notoriously difficult to establish a causal connection between industrial policy and economic growth. Apparent “market failures” are often the result of prior government interventions. Moreover, the political nature of industrial policies makes them vulnerable to capture by special interests.

This insight leads into a chapter about the dangers of cronyism titled “Business against the Market.” Here Gregg covers not just old saws about established firms’ efforts to restrict entry into their markets but also newer developments such as “stakeholder capitalism,” currently being promoted by influential groups such as the World Economic Forum. Gregg argues that these advocates’ attempts to require Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) disclosures from corporations and other such initiatives are really a throwback to the discredited corporatism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that stunted the economies of countries such as Italy and Portugal and created environments conducive to corruption and inimical to accountability. Under current conditions, every move towards adopting the stakeholder capitalism model increases the potential for woke activists to seize control of companies and direct their resources toward their social and political agendas.

Gregg’s antidote to state capitalism is laid out in the three chapters of the book’s second part: creativity, competition, and trade. Entrepreneurship and innovation have driven the American economy for most of its history, but in recent decades these have declined according to several measures. Gregg calls for a strengthening of the institutional framework for entrepreneurship and the removal of regulatory barriers that prevent capital from getting into the hands of people with new ideas. As part of this call for dynamism, Gregg urges policymakers to remain favorable to immigrants who are likely to become entrepreneurs and who share a cultural commitment to ordered liberty.

Gregg acknowledges that free marketers “oversold the case for free trade from the 1980s onwards” by implying that open markets would inevitably bring about political reforms in countries like China. He also concedes that “trade policy cannot be separated out from foreign policy considerations” and that “defense trumps opulence.” At the same time, he insists that openness to international trade is essential for America’s long-term prosperity and competitiveness, so we must not embrace a general posture of protectionism. He also warns that protectionists are often tempted to invoke national security concerns in unjustifiable ways when lobbying for specific regulations, and these must always be subjected to careful scrutiny.

Gregg effectively shows that embracing the state capitalism model would be a dangerous gamble. One wonders whether a shorter, more tightly written work with a more journalistic flair could have had a bigger impact on its intended readership. Nevertheless, this book is a solid addition to the debate over economic policy in a time when defenders of the free market appear to be on the defensive.

Buckley is a supporter of the market economy in general, but his case for it in Progressive Conservatism is pragmatic and consequentialist rather than philosophically a priori. Whereas Gregg sees a more consistent implementation of market principles as the remedy for cronyism, Buckley is more focused on defanging the political class in ways that the average voter is likely to support. He wants a new standard-bearer for a policy program in what he calls the “sweet spot” of American politics: a moderate welfare state combined with a moderate social conservatism. If Republicans can consistently put forward candidates with this vision, he writes, they will become “America’s natural governing party.”

Buckley begins with a chapter titled “The Dream of Republican Virtue.” Historically, he writes, ordinary Americans saw themselves as possessing a certain purity. They were tough on the outside but soft on the inside. They shunned corruption and maintained their optimism and confidence even when surrounded by hardship. But the political left has nearly destroyed that vision in recent decades by insisting that we “remember everything terrible about our country and ignore anything good.”

The conservative movement’s leadership largely remained silent before the culturally leftist tide, refusing to show courage on issues such as border security and leftist activism in public education. In response, the Republican rank and file turned in frustration to Donald Trump, the “Hegelian hero,” in 2015 and 2016: “The Never Trumpers told us that if we nominated Trump, it wouldn’t end well. But it’s so much better than anything you have, we answered. It turns out that we were both right.” Trump campaigned on a winning policy agenda that Buckley wants to see further developed by the next generation of Republican leadership.

Buckley lays out his case for “progressive conservatism” over sixteen chapters organized into five parts. The titles of the book’s main divisions give a fair indication of where Buckley thinks Republicans should focus their efforts: “Progressive and Conservative,” “Restoring the American Dream,” “Draining the Swamp,” “Nationalism,” and “The Promise of Good Government.” He believes Republicans can garner the support of large majorities of Americans in each of these areas of emphasis.

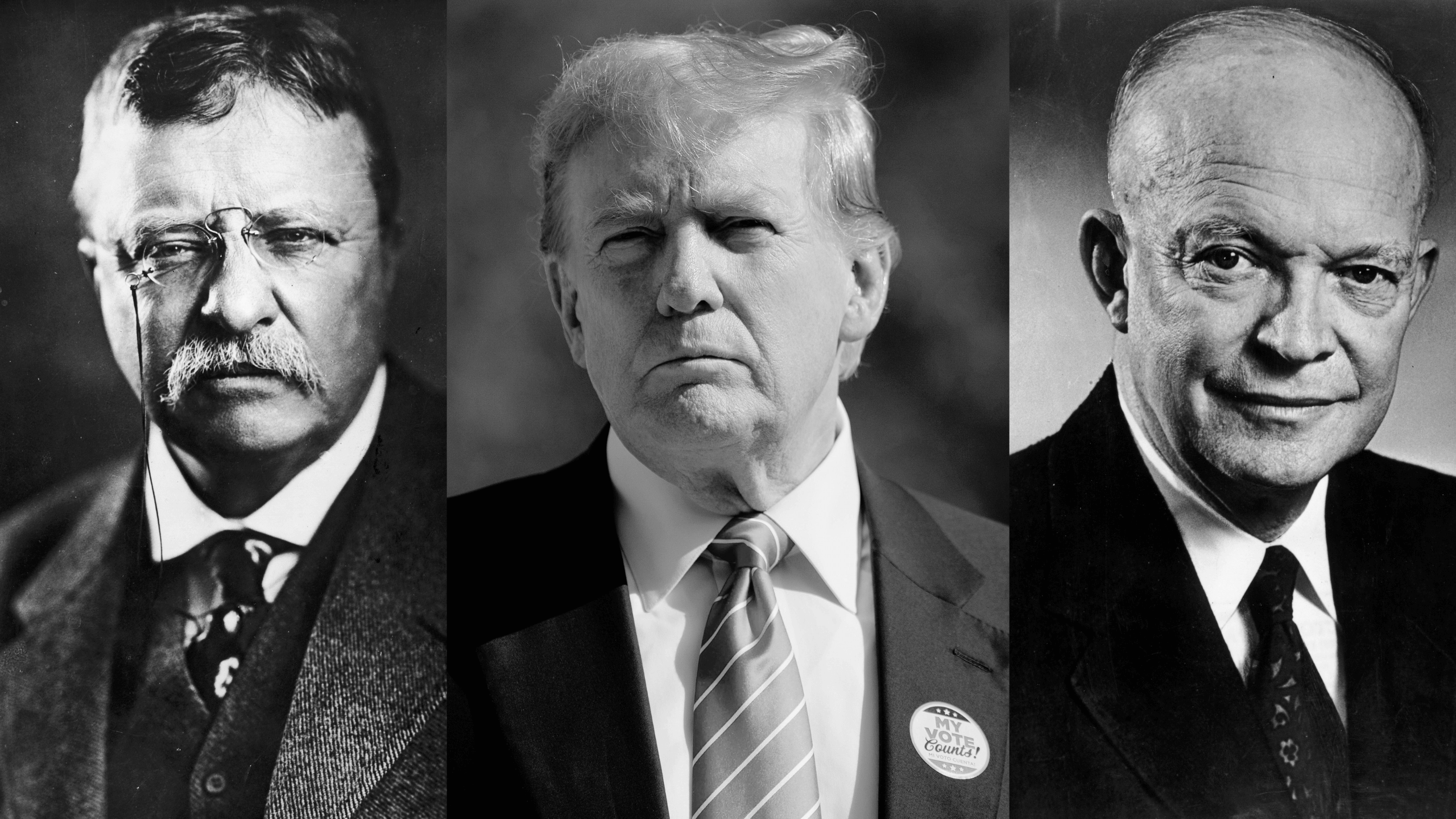

Buckley places the Trump presidency as the latest in a line of four progressive Republican administrations following those of Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, and Dwight Eisenhower. Each of these presidents emphasized a vision of America as a land of social mobility and economic opportunity in opposition to voices claiming that a socially and economically stratified society was inevitable and perhaps even desirable. Lincoln emancipated slaves, Roosevelt busted trusts, Eisenhower advanced the civil rights agenda, and Trump challenged the entrenched managerial elite, at least in his rhetoric. This orientation is what Buckley means by “progressive conservatism,” and he calls it the “secret code” of American politics.

A few examples will illustrate the overall thrust of Buckley’s argument. America suffers from a crisis of social immobility today, but this problem is not the result of free-market capitalism or its representative “high tech gazillionaires.” Rather, our system is dominated by “the country’s managerial class and a professional class of executives, lawyers, and lobbyists” who make up perhaps 10 percent of the population. Below them, the rest of us must navigate “the broken educational system, the absurd immigration policies, and the regulatory barriers” this class has created.

The elite congratulates itself for building a system based on diversity, equity, and inclusion, while simultaneously insulating itself from most of the negative consequences that system creates for ordinary people. Its members send their children to private schools so they don’t suffer under the mediocrity created by the teachers’ unions, who in turn give the elite critical political support. The elite’s open-borders policies for unskilled workers provide its members with cheap maids and nannies while depressing wages for the native-born working class. Our “regulatory briar patch” provides employment for armies of lawyers, lobbyists, and bureaucrats at the same time that it raises the prices of most goods and services and squeezes lower-income Americans out of the housing market and other areas of the economy.

In the last decade, public corruption has returned to the forefront of American politics. Trump capitalized on this issue in 2016, and Buckley believes it will continue to be a winning issue for Republicans who can present credible arguments about “draining the swamp.” He makes the important point that not all corruption is illegal. Campaign contributions, for example, purchase access to officials in a constitutionally protected way, though the collapse of donations to the Clinton Foundation after the 2016 election was clear evidence that donors were “paying to play.” Buckley cites Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), which ranks the U.S. at number 25, behind most developed countries: “We score moderately well on competitiveness and country-level risk and not at all well on the rule of law.”

In response to these and other challenges, Buckley urges Republicans to offer a new, twelve-point Contract with America. He proposes a “jobs economy” that encourages family formation by making men better marriage prospects; far-reaching school choice and higher education reform (including bankruptcy relief for student debt); a points-based immigration system similar to the one used in Canada; an initiative to identify critical regulations to maintain while scrapping the rest; and anti-corruption reform that “close[s] the door between K Street and Congress.” He also calls for a national catastrophic health insurance plan, election reforms to ban ballot harvesting and the abuse of absentee voting, the creation of a social media court to put a stop to the suppression of “legitimate political views” on major platforms, and a concerted effort to instill a sense of “benign” national identity in the American populace.

Buckley’s presentation has its flaws, to be sure. His broad-brush treatment of American history gets some particulars wrong. He claims the New Deal was successful to the extent that it got America back to work, a position that economic historians sometimes advanced half a century ago but have abandoned in more recent decades. He blames the GOP’s loss of Congress in the 1954 elections on right-wing opposition to federal insurance subsidies—no mention of the backlash to McCarthyism. He attributes George H. W. Bush’s 1992 loss to Ross Perot’s third-party candidacy, even though exit polls showed Perot pulling supporters from Bush and Bill Clinton at about the same rate. And he makes the astounding claim that Russell Kirk “forgot” the Burkean insight that “traditions sometimes stand in need of reform.”

An effective counterbalance to these occasional errors is Buckley’s sparkling prose, which compares favorably to most of what is on offer from the political right these days. Many passages in the book are a joy to read. For example, when describing the media’s relationship to Trump, he writes: “If he said that new federal buildings should be in a classical style, they would discover that brutalism was cool again. If he wanted to make America great again, they answered that it was never great.” On the coverage of Hunter Biden: “The son was discharged from the Navy for his cocaine use and fathered a child with a stripper while dating his brother’s widow, but the New York Times thought the real story was Hunter Biden’s new career as an amateur painter. ‘There’s a New Artist in Town. The Name is Biden.’ If you want some doors opened for you, perhaps you might want to buy one of his paintings. They’re going for $500,000.”

Yet Progressive Conservatism has a big problem: it is a book written for a post-Trump Republican Party. Buckley washed his hands of Trump after January 6, 2021, and believes he cannot be the standard-bearer of progressive conservatism going forward. Chapter 2 is titled “After Trump”; it includes the heading “The Need to Move On.” But as the current election cycle is clearly demonstrating, the post-Trump GOP does not yet exist, and relatively few Republicans are heeding the call to bring it about.

How ought the political right to respond to Buckley’s agenda? There would certainly be internal debates over which level of government (federal or state) should implement some of his reforms and whether, for example, his health-care proposal could be justified as a move in the direction of a market-oriented system on balance. Nonetheless, it seems likely that there could be broad agreement on most or all of the planks in Buckley’s platform. This likely consensus makes it all the more curious that Buckley repeatedly takes swipes at libertarians and others on the conservative movement’s “right wing.” One passage, for example, characterizes National Conservatives as “objectively anti-American.”

It seems that Buckley’s Contract with America and Gregg’s call for a recommitment to the free market are largely compatible. International trade and industrial policy do not figure prominently in Progressive Conservatism, but in the areas of regulatory and immigration reform the two authors—both of whom are immigrants—appear broadly in agreement. Gregg, who is generally pro-immigration, acknowledges that the sovereign nation-state can legitimately manage the inflow of migrants with an eye toward the common good of the nation’s citizens, and Buckley’s point-based system would probably accomplish that. Conversely, Buckley’s proposal for a regulatory commission that would eliminate the majority of the Federal Register’s text would almost certainly be music to Gregg’s ears. Most of the rest of Buckley’s Contract with America relates to economic policy only tangentially.

A pragmatist might argue that Buckley’s plan is the right strategy for the GOP in the short term while also acknowledging the need Gregg identifies for a longer-term revitalization of America’s culture of creativity and competition. The question is whether the different factions on the right represented by Gregg and Buckley can coalesce around a coherent policy agenda of any sort, to say nothing of a particular presidential candidate, after many years of focusing on their differences instead of what they have in common. Perhaps if the fusionists can learn to speak more effectively to working-class concerns, and if the progressive conservatives can give the market at least two or two-and-a-half cheers, that coalition could come about.