Ten years ago, a group of eminent men from the United States and several European countries met at Mont Pélérin, in Switzerland, to discuss the condition under which a society of free men can exist today.1 They had in common a social philosophy which might be called “liberal,” if this word had not become the source of many misunderstandings.

None of us there believed that a socialist economy could result in anything but misery and serfdom, and we all were convinced that collectivism in all its forms is the real danger threatening our civilization. We discussed the necessity for re-establishing a regime of active competition; and in the course of our meetings we touched upon technical questions in the spheres of economics and jurisprudence. Most of us, indeed, were economists: familiar with the theories of supply and demand, of the prices of the factors of production, and of money. There was no one among us who was an active representative of the Catholic faith.

Then there happened something which shows strikingly the almost funereal gravity of our present hour. In this circle of technicians, the discussion turned upon the increasing conviction that if we intend to win the battle for freedom, we must pay attention not primarily to supply and demand, but to quite different things; and once the ice was broken, we “hardened liberals” spoke of what Christianity means for freedom—and, inversely, of what freedom means for Christianity. We were conscious that in speaking in the first place as Christians or liberals concerned for freedom and human dignity, we were on common ground: ground we did not share with the enemy.

One of us, Professor Eucken—who, since then, has died before his time—spoke of the experiences of the Third Reich, where men finally were driven to ask themselves if a man might be a Christian under a totalitarian regime, since such a domination deprives him of the freedom of moral decision essential to Christianity. He added that common suffering had overthrown the old confessional barriers, and that both Protestants and Catholics worked in the same direction, or even together, to attain a common goal: the development of a political and economic order which would be the opposite of a totalist society and economy, and which would express both Christian and liberal ideals. Since then, this collaboration has culminated in Germany in the foundation of the Christian Democratic party, led by Dr. Adenauer.

In the course of our discussions at Mont Pélérin, we entered fully into the question of the relationship between liberalism and Christianity. I believe that this question can no longer be neglected. It merits a fresh examination. In this undertaking, it is desirable to speak of liberalism in a double sense: first, in the general sense of an idea which expresses the essence of our civilization; and, on the other hand, in the narrower and more specific sense of an intellectual, economic, and political ideology, born in the nineteenth century under the influence of certain factors proper to that period. In the first sense we are, indeed, all liberals so soon as we are anti-totalitarians. But if the word is taken in its second meaning, it is doubtful if any one of us can still call himself a liberal. Liberalism in the first sense is, as I have written elsewhere,2 a giant tree which blossomed in a respectable age: under its ample foliage we are at this moment assembled with the feeling in our hearts that we have something in common to defend, whether we be conservatives or democrats, liberals or socialists, Protestants or Catholics. In its second meaning, on the contrary, liberalism is only the newest offshoot of this tree, and more than one person is wondering if it is not a savage growth. It would be criminal to wish to cut down the tree because the newest branch does not suit us; nevertheless, a thousand hatchets are already at work to commit this crime.

He who counts as precious the essential values and ideals of our Western civilization, so precious that he would be willing to defend them to his last breath—such a man knows what we mean when we speak of this tree, that is to say, of liberalism in its large and loftier meaning. For in the shape of this tree he honors the valuable work of centuries, yes, even of millenniums, a heritage which goes back to the origins of our civilization, to the Ionian Greeks, to the men of the Stoa, to Aristotle and Cicero. He reflects on all those thinkers of antiquity who were among the first to speak of human dignity and of the absolute nature of the individual soul in terms that could be understood by all rational men—who discovered the kingdom of ideas, who opposed human caprice, who proclaimed the inviolability of an order beyond the State—ideals which became the guiding stars of Western thought. What the animae naturaliter Christianae launched, was completed in a grand way by Christianity and transmitted to us as Christian natural law. Christianity was necessary to wrest man, as a child of God, from the grasp of the State and to undertake (in the words of Guglielmo Ferrero) the destruction of the “Pharaonic spirit” of the State of antiquity.

Most of us are still moved to wonder how it was possible for the Ancients to have had a concept of freedom so different from our own.3 In effect, their notion of the collective freedom of the “sovereign people” did not exclude the total subjection of the individual; we find the idea of freedom in this form in the ancient polis, and it occurs again in Rousseau; it is at the base of the doctrinaire ideology of modern democracy. Our idea of freedom, on the other hand—the Western idea—is of a freedom which guarantees the rights of the person, limits the action of the State, and comprehends the rights of the individual, of the family, of the minority, of the opposition, of religious groups. Western man has been at pains to point out that the wall which at this point separates him from the Ancients is Christianity, that Christianity to which we owe the phrase: Render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s, but to God the things which are God’s. If we reflect upon the whole meaning of this phrase, we recognize that it expresses, after all, what is in our minds when we speak of liberalism in its widest sense.

It is, therefore, our common inheritance from antiquity and Christianity with which we are concerned here. Both are the true ancestors of a philosophy which defines the always tenuous relationships between the individual and the State in accordance with the postulates of universal reason and of human dignity—a philosophy which conforms to the nature of man, and thus opposes personal freedom to the power of the State. A précis of liberalism could be written using only the orations of Cicero, the Corpus Juris, and the Summa of Aquinas; it would be vividly contemporary. In all of these works, we discover the venerable patrimony of the personalist philosophy, but perhaps nowhere do we find it more distinctly than in the political philosophy of the Catholic Church through all of its changes and vicissitudes.

Without bias, and excluding resolutely any ideas merely negative, we ought to examine Catholic social philosophy in all its sources, works, and documents, and in all its aspects, to find out it is akin to our idea of universal liberalism. This is a tempting task. To those of us who are concerned with the philosophical bases of liberalism and who seek to free liberalism of the fatal errors of the nineteenth century, such a study may reveal the extent of the debt we owe to Catholic thought. It may also show that a goodly number of liberal thinkers—among whom are Tocqueville and Acton—were good Catholics, and that even a man like G. K. Chesterton did not hesitate to call himself a liberal. Perhaps in this way we may overcome the hesitancy of more than one Catholic to make an unbiassed re-examination of the case for liberalism.

For the grave problems of the modern age oblige us, regardless of our position, to examine afresh our social philosophy, that we may realize exactly where the common front lies, and thus avoid useless controversy. I may illustrate what I mean here by referring the reader to that solemn document of the Catholic Church, the Encyclical Quadragesimo Anno, which appeared on the 15th day of May 1931. While I have space only for a brief investigation of this document, I should like to suppose that the serious reader is interested in learning of the attraction it has for a Christian and a liberal who is not a member of the Catholic Church—although one who pretends to no skill in exegesis. But such a man—and this is the essential point—who in the higher and more general sense can call himself a liberal, will not hesitate to declare that this Encyclical is one of the most impressive, profound, and noble of manifestoes, in which many things close to the hearts of all of us, are expressed with a dignity, with a vigor of conviction, and with a comprehensiveness of view which are rare. Indeed, the “liberal” quintessence of this document cannot be denied, so long as we take this word in its large and eternal sense of a civilization based on man and upon a healthy balance between the individual and community; so long, in short, as we accept liberalism as the antipodes of collectivism.

I know that in making this brief observation I shall encounter the objections of those who are accustomed to see in the Encyclical an anti-liberal program of the “Corporate State,” and who hold it in good or bad memory depending on their political opinion. It seems to me that this is the result of an erroneous interpretation which today might well repel the favorable opinion the Encyclical merits. He who takes the trouble of reading it with care and without bias (and, in case of doubt, refers to the Latin original) will have difficulty in seeing how the Encyclical could have been interpreted as a program of Corporatism were this interpretation not based upon a confusion of ideas to which the term “Corporatism” can certainly lead, but a confusion which cannot be excused today.4 Let us not forget that the corporate state and the corporate economy are expressions which have meaning only if the “corporation”5 (ordo in the original) becomes the structural principle of the State or of the economy. If it is made the basis of the State, it will replace the principle of existing democracy (representative, parliamentary, or direct): and will make of the corporations, organs which express the general will. Likewise, if the corporation becomes the structural principle of the economy, it will replace the existing principle, notably the market, by the concord or discord of the corporations (skeptics would say by vested interests). In the first case (the case of the corporate state), corporatism is opposed to all democracy; in the second case (that of the corporate economy), it destroys the economy of the market.

Even with the best will, I have been unable to find any trace of such a corporatism in the Encyclical, not to speak of the disapproving way in which the Encyclical treats the corporatism of Fascist Italy of the period. In each place where the “ordines” are mentioned and where their establishment is recommended, it is done simply with the social purpose of obtaining an improvement of the relations between employers and employees, that is to say, with the aim of dissipating the class struggle, and not of killing competition in the market. Even in this restricted meaning of corporation (professional community as we would translate the word ordo in our day), as an instrument of social reform (and not of economic reform), the Encyclical stresses free will before all else. One is continually under the impression that the author of the Encyclical had before his eyes the dangers arising from an imprudent recommendation of corporations, and that to avoid an anarchy of “group interests,” he endeavored to restrict this organization to the sphere of social reform.

This impression is, moreover, confirmed when, in answering the question whether the structural principle ought to be collectivist or non-collectivist, the Encyclical decides in favor of the market economy (haec oeconomiae ratio) and against a controlled economy. Such a position, obviously, does not exclude rejection of the aberrations of the market economy. I have been unable to find in the Encyclical any passage sanctioning the belief that an order based on the market economy should be replaced by another which can only be a collectivist order, exception being made for the sector in which an autonomous peasant economy prevails. The latter is given its due estimation (III.1).

In my opinion, one of the very great merits of the Encyclical is that it makes a clear distinction between the principle of the market economy as such and its numerous deviations. It does this precisely in order to attack the latter and save the principle of the market, and thus rescue our economic system from an omnivorous collectivism. This is exactly what the representatives of neo-liberalism hold, though they formulate it in a different way. This is more clearly realized when we note that the Encyclical sees the degradation of the market economy not only in the excesses of an outdated policy of laissez-faire, but also in the progressive disfigurement of the competitive order by monopoly. Doubtless, I would here emphasize certain things, which the Encyclical does not, and occasionally, perhaps, I would express myself in different language to obviate misunderstanding. Thus, I hesitate to accept the Encyclical’s point of view on monopolies, which it imagines to be the creations of free competition; in my opinion, they are rather the result of insufficiencies in the legal framework and of a certain brand of state interventionism. But I can only acquiesce with joy when the Encyclical goes to war against monopoly (oeconomicus potentatus) and its disastrous economic and political consequences (in particular III.1).

When it stigmatizes the “debasement of the dignity of the State which should place itself above the quarrels of special interests,” it directs itself against a monopoly sclerosis of the market economy and against group anarchy—diseases which, on this one hand, paralyze the market by making impossible any just balance between what is given and what is taken in return and, on the other hand, dissolve the State by their “pluralism.” We cannot at the same time fight the “special interests” and recommend economic policy which would sanction and even aid their fatal growth. That, however, is what corporatism would do; only the reestablishment of real competition can provide a remedy at this point. It would impugn the perspicacity of the author of the Encyclical to understand him as meaning anything else.

If the concentration of power in the hands of private persons is a great evil, it becomes a still greater evil in the hands of an all-powerful State armored with political sanctions. This truth does not escape the Encyclical despite its emphasis on rendering to the State the things which are the State’s. Thus it is led, as are all of us, to a war on two fronts: against tho individualism and economic policy of laissez-faire, and against collectivism. The fact that the Encyclical should reject collectivism and individualism with equal intransigence is all the more significant in view of the omnipresent danger to see in socialism (collectivism), in its theory at least, a genuine Christian doctrine, or at least an emphasis on moral values and sentiments which are specifically Christian. The very fact that it has clearly taken a position is the great merit of the Encyclical; now that we are again hearing vague talk about a “Christian Socialism” we would do well to recall these clear and authoritative words: “whether Socialism be considered as a doctrine or as an historical fact, or as a movement, if it really remains Socialism, it cannot be brought into harmony with the dogmas of the Catholic Church, even after it has yielded to truth and justice in the points we have mentioned; the reason being that it conceives human society in a way utterly alien to Christian truth” (III. 1). Even the “moderate socialists” receive a severe warning (Communism being considered as beyond discussion). If their moderation resides in the fact that they confine their activity to certain reforms which can just as well be supported by a non-socialist ideology, (e.g., the struggle against monopoly concentration), “then,” says the Encyclical, “they abuse the term Socialism.”

The Encyclical has taken up its position between two extremes so that it may seek a “third road” to avoid the “dangers both of individualism and collectivism.” In what direction does this third road lead us? On this point the Encyclical furnishes some remarkable details. I shall speak first of its exposition of the problem of Property. In our industrial age of huge corporate holdings, the concept of property needs redefining, if it is to withstand criticism. The Encyclical speaks of the double nature of property, of its individual and social functions; and it proves that exaggeration of the latter leads to collectivism. Though it underlines the responsibility which attaches to the possession of the means of production, a responsibility which arises out of the social function of property, the Encyclical is no less emphatic in affirming the inviolability of property. In view of the recurring temptation to make of property a relative thing by appeal to the Gospels, the Encyclical takes a further stand: “Man’s natural right of possessing and transmitting property by inheritance must be kept intact and cannot be taken away from man by the State. Hence, the domestic household is antecedent, as well in idea as in fact, to the gathering of men into a community.” The final remarks of the Encyclical may be added here: “Those who are engaged in production are not forbidden to increase their fortunes in a lawful and just manner: indeed, it is just that he who renders service to society and develops its wealth should himself have his proportionate share of the increased public riches” (III. 3b).

It is upon this eminent social philosophy which respects a rational natural order that the third part of the Encyclical is based (II.1). This is the part which treats of social questions and in my opinion it surpasses all the others. The high point of its argument occurs when the Encyclical, without undervaluing traditional social policy, rightly situates the real problem in a process of decomposition: a decomposition which is not essentially material but spiritual and anthropological; a process which may be summed up in the word: proletarianization. The solution of the social problem and the solution to the problem of de-proletarianization (redemptio proletariorum) are inseparable; and the Encyclical further declares, with justice, that our civilization hangs upon the solution of these problems. It is impossible here for me to give an adequate summary of the many other considerations which ought to be taken into account. I confine myself to the observation that the world would long since have done well to impregnate itself with the social doctrine and the spiritual tradition of this Christian philosophy.6

It would be superfluous to dilate further on the fact that such a program of de-proletarianization is at the same time a program of economic, social, and political decentralization, or better, a program of the “aerated society” (Gustave Thibon); that it is in every respect the opposite of economic collectivism and of political totalitarianism—a program, too, which has nothing in it of the romantic but is rather built on realism since it considers man in his milieu and as subject to his natural necessities, and since, finally, it puts reason above the unreal or the anti-natural of the actual world.

Behind this Encyclical we sense the able economist who does not lose himself in vague postulates, but, like the “liberal” economist, remains aware of the interdependent relationships of economics. Because he has carefully avoided viewing the social problem merely as a question of wages, the author of the Encyclical makes the legitimate observation that it will not suffice to raise wages without considering these interdependent economic relationships. He makes it plain that an arbitrary raise in wages, indeed, is closely linked with unemployment (III. 3c). The informed economist is once more revealed when the reform of industrial corporations is seen as an important condition for the improvement of economic life (III. 3).

Only now and then does the Encyclical mention the problems of the international economy. Considering the importance of this domain, this omission is regrettable. If I am not mistaken, the position of Catholic social philosophy is least definite with respect to these problems. But it seems that recently an increasing number of voices have declared that on the international level, the sociological and economic principles of the Encyclical lead to adherence to the principles of a free, “multilateral” world economy. That is precisely the kind of international economic order desired by truly liberal thinkers.7

Perhaps the average Catholic may balk at speaking in terms of a “liberal” world economy. It is not easy to abstract what is essential from the association of nineteenth-century ideas implied by the word “liberal”; there is an understandable hesitation to employ this word in its general meaning—that meaning which, nevertheless, expresses so well a social philosophy specifically Catholic.

In the last analysis, it may be answered that words count for little. What matters is that we recognize our entry into the decisive phase of the battle for freedom and the dignity of man; and, or in this battle, the patrimony of Christian social philosophy which, increasingly, merges with all that is essential and enduring in liberalism.

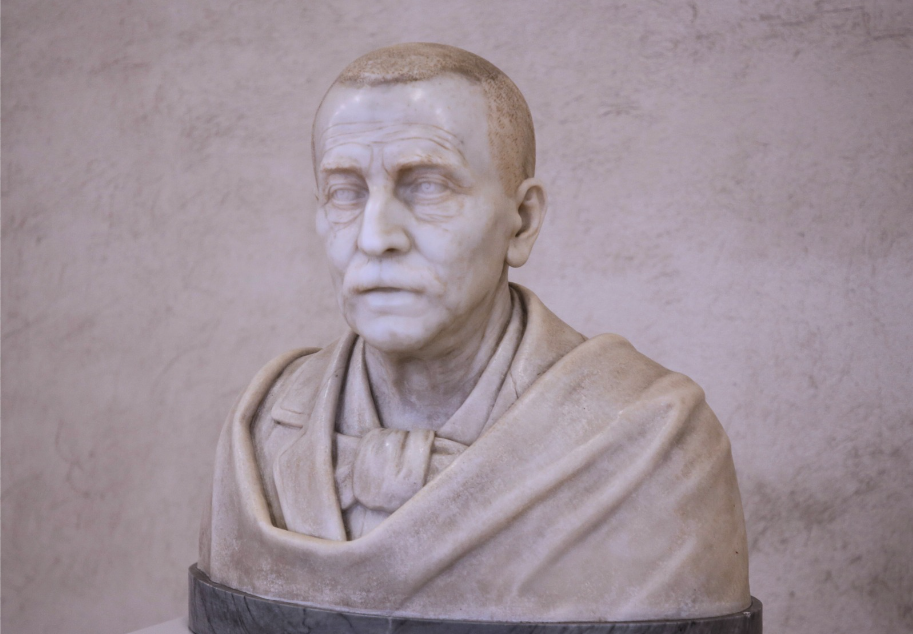

Wilhelm Röpke was a German economist and author, best known for his work, A Humane Economy (1958).

*translated by Patrick M. Boarman

- The group included Wilhelm Röpke, William Rappard, and Hans Barth from Switzerland; Jacques Rueff and Bertrand de Jouvenel from France; Luigi Einaudi and Carlo Antoni from Italy; Walter Eucken from Germany; Friedrich Hayek, Lionel Robbins, John Jewkes, E. Eyck, Michael Polanyi, and S. R. Dennison from England; Karl Brandt, Henry Hazlitt, Ludwig von Mises, and George Stigler from the United States. ↩︎

- In my book Mass and Mitte (Zurich, 1850). ↩︎

- Perhaps the most noteworthy treatment of this question is the essay by Benjamin Constant: “De la liberté des Anciens Comparée à celle des modernes.” (Oeuvres Politiques, Editions Louandre, 1874). ↩︎

- Here I refer the reader to my own books, in particular, The Crisis of Our Time (University of Chicago Press), and Civitas Humana (W. Hodge, London, 1948). ↩︎

- Corporation as used in this context is a general term meaning a group of persons organized on professional lines. It must not be confounded, therefore, with the business corporation of American law. ↩︎

- In addition to the writings of G. K. Chesterton (especially Outline of Sanity) and of H. Belloc, Goetz Briefs’ The Proletariat must be mentioned. Also, the wholesome and refreshing works of the French Catholic peasant philosopher Gustave Thibon (Diagnostics, Essai de Physiologie sociale, Retour au Réel). Of Belloc, see especially: An Essay on the Restoration of Property. ↩︎

- See the interesting book by the former editor-in-chief of L’Osservatore Romano, Guido Gonella, Presupposti di un ordine internazionale (Vatican City, 1942). For my own ideas, see my book Ordnung-beube (Zurich, 1954), and my English lecture delivered at the Academy of International Law, “Economic Order and International Law” (Leyden, 1955). ↩︎